Adams Morgan

Adams Morgan is a neighborhood in Northwest Washington, D.C., centered at the intersection of 18th Street NW and Columbia Road, about 1.5 miles (2.54 km) north of the White House. Known for its broad mix of cultures and activities, Adams Morgan contains together both residential and entertainment areas, and has a vibrant nightlife with numerous bars and restaurants, particularly along 18th Street NW. Columbia Road also holds a busy stretch of shops and businesses.[1] As a distinct, named area, Adams Morgan came into being in the late 1950s, when it drew together several smaller and older neighborhoods that were first developed in the latter 19th and early 20th centuries. It is today composed primarily of well-made rowhouses; and classically-styled mid-rise apartment buildings, many of which are now co-ops and condos; along with various commercial structures.

Adams Morgan | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Washington, D.C. | |

Stores and cafes along 18th Street NW | |

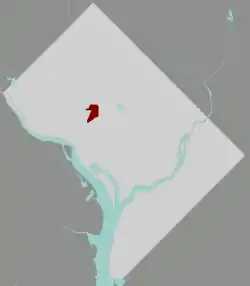

Adams Morgan within the District of Columbia | |

| Country | United States |

| District | Washington, D.C. |

| Ward | Ward 1 |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Brianne Nadeau |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.47 sq mi (1.2 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 15,830 |

| • Density | 33,601.3/sq mi (12,973.5/km2) |

Adams Morgan is bounded:

- to the south, by Florida Avenue NW and the Dupont Circle neighborhood

- to the southwest, by Connecticut Avenue NW and Kalorama-Sheridan

- to the north, by Harvard St. and Mount Pleasant

- to the east, by 16th Street NW and Columbia Heights

Reed-Cooke is a sub-neighborhood of Adams-Morgan, consisting of the easternmost area between Columbia Road and Florida avenue.

History

Before the colony of Maryland was established in 1632, the area of today's neighborhood was home to the American Indian, Nacotchtank tribe. Robert Peter and Anthony Holmead, two prominent colonial-era landowners, held the land beneath Adams Morgan when the District of Columbia was created in 1791. At that time, these local tracts sat just above the original planned City of Washington, and were either undeveloped or only lightly farmed. As the population of D.C. expanded, this land was divided into several estates purchased by wealthy residents, including Meridian Hill, Cliffbourne, Holt House, Oak Lawn, Henderson Castle, a part of Kalorama, and the horse farm of William Thornton.[2] After the Civil War, these estates were subdivided and the area slowly grew. Once the city's overall-layout plans were finalized in the 1890s, these various subdivisions, using modern construction techniques, developed more rapidly, and the area of Adams Morgan then grew into several attractive and largely upper- and middle-class neighborhoods.

In the 20th century, the area was home to a range of people, from the very wealthy living along 16th Street, to white-collar professionals in Lanier Heights, to blue-collar residents east of 18th Street NW. Residents comprised all classes and a mix of races, though segregated. After World War II, the modern development of the nation continued, and racial desegregation began. When D.C. was formally desegregated, some whites abruptly left the area, other whites stayed and worked to integrate the neighborhood, and some African Americans and Hispanics moved into the area. The neighborhood, along with the city, was evolving. The area, with its less costly housing, also became home to some artists and social activists.

The name Adams Morgan, once hyphenated, is derived from the names of two formerly segregated area elementary schools—the older, all-black Thomas P. Morgan Elementary School (now defunct) and the all-white John Quincy Adams Elementary School.[3] Pursuant to the 1954 Bolling v. Sharpe Supreme Court ruling, district schools were desegregated in 1955. The Adams-Morgan Community Council, comprising both Adams and Morgan schools and the neighborhoods they served, formed in 1958 to implement progressively this desegregation. The city drew boundaries of the neighborhood through four existing neighborhoods—Washington Heights, Lanier Heights, Kalorama Triangle, and Meridian Hill—naming the resulting area after both schools.[4]

Since its formation in the 1950s, Adams Morgan and its community have stood for social justice, political activism, and inclusive, progressive values. Nearby All Souls Unitarian Church, the Potter's House cafe and bookstore, and Meridian Hill Park have all served as gathering places for activists dedicated to social change, and also function as civic centers of the greater community.[5]

In the late 1960s, a group of residents organized and worked with city officials to plan and construct a new elementary school and recreational complex that was conceived as a community hub, a concept that 40 years later has become a standard in public school facilities design. The development was named the Marie H. Reed Learning Center after the minister and civic leader.[6] It featured a daycare center, tennis and basketball courts, a solar-heated swimming pool, health clinic, athletic field and outdoor chess tables.

Since the 1990s, Adams Morgan has seen an influx of new residents, as more people are continuing, in general, to move into urban centers. New housing is being constructed—some new infill-construction, some developments that use repurposed structures, and some new construction that is replacing older industrial buildings in parts of the Meridian Hill area. Some of these new and redeveloped apartment buildings are being constructed along 16th Street NW. The new residents include a mix of young professionals and older people returning from the suburbs.

From 2010 to 2012, the city reconstructed 18th Street NW, one of the neighborhood's main commercial corridors,[7] with wider sidewalks, more crosswalks and bicycle arrows, resulting in a more pedestrian-friendly thoroughfare. Additionally, the Adams Morgan Partnership Business Improvement District (AMPBID) has been active in the community since 2005; its stated mission is to promote a clean, friendly and safe Adams Morgan.[8] Currently it sponsors local events such as summer concerts and holiday decorations, and provides helpful information to the area residents.

Cultural diversity

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1950 | 21,000 | — | |

| 1960 | 18,097 | −13.8% | |

| 1970 | 18,573 | 2.6% | |

| 1980 | 15,352 | −17.3% | |

| 1990 | 15,061 | −1.9% | |

| 2000 | 14,803 | −1.7% | |

| 2010 | 15,830 | 6.9% | |

Along with its adjacent sister communities to the north and east, Mount Pleasant and Columbia Heights, Adams Morgan long has been a gateway community for immigrants. Since the 1960s, the predominant international presence in both communities has been Latino, with the majority of immigrants coming from El Salvador, Guatemala and other Central American countries. Since the early 1970s, like other areas of the nation, Adams Morgan had seen a growing influx of immigrants from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean, as well. Gentrification and the resulting higher cost of housing, however, have displaced many immigrants and long-time African American residents, particularly those with young children, as well as many small businesses, but the community still retains a degree of diversity, most evident in its array of international shops and restaurants. Since 1980, the population of the neighborhood has not changed (increasing marginally from 15,352 to 15,630) while average real annual household income more than doubled from $72,753 to $172,249 (in 2010 $) and diversity has decreased shifting from 51% to 68% White Non-Hispanic.[9]

Adams Morgan also has become a thriving spot for nightlife, with several bars and clubs featuring live music. Over 90 establishments possess liquor licenses, putting it on level with other popular nightlife areas like Georgetown and Dupont Circle. Nightlife establishments rapidly replaced local stores along 18th Street NW, leading the Alcohol Beverage Control Board to impose a moratorium on new liquor licenses in 2000 after successful lobbying by resident groups. The moratorium was renewed in 2004, but eased to allow new restaurant licenses.

Despite the exodus of many immigrant, and also African-American, residents from Adams Morgan because of costlier housing, a nexus of long-time institutions, many established specifically to meet the needs of Latinos and other non-English-speaking residents, continues to serve as a magnet for immigrants and their families. Within Adams Morgan is Mary's Center, a clinic focusing on healthcare delivery to Spanish-speaking patients, and the Latino Economic Development Corporation, and numerous businesses and churches that employ and cater to immigrants. Adjacent Mt. Pleasant also hosts a number of commercial enterprises, social service agencies and other institutions that help to anchor local immigrants to the area.

Another barometer of the enduring pull of Adams Morgan for immigrants is the linguistic and cultural diversity of its public schools. Many of the families served live beyond the boundaries established for routine student enrollment; however, Adams, Reed, and H.D. Cooke elementary schools all have international populations, with children from well over 30 nations in attendance. Latino and African-American children comprise the majority of students in the public schools.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The second Sunday of September, the neighborhood hosts the Adams Morgan Day Festival, a multicultural street celebration with live music and food and crafts booths. Weather permitting, every Saturday—except during the coldest winter months—local growers sell fresh, organically grown produce and herbs, baked and canned goods, cheeses, cold-pressed apple juice, and fresh flowers at the farmers market, in operation in the same location on a plaza at the corner of 18th Street NW and Columbia Road for more than 30 years.

In the 1960s, the neighborhood's attractions included the Avignon Freres bakery and restaurant (closed in the 1990s), the Café Don restaurant, the Ontario motion picture theater, and the Showboat Lounge jazz nightclub. In the 1980s, Hazel's featured live blues and jazz, and its soul food offerings made it a favorite of black jazz musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie when they came to town.

In September 2014, the American Planning Association named Adams Morgan one of the nation's "great neighborhoods", citing its intact Victorian rowhouses, murals, international diversity, and pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly streetscape.[10]

Transportation

The area is not directly served by the Metrorail system. The station nearest the heart of Adams Morgan, Woodley Park, is in the Woodley Park neighborhood, but was renamed "Woodley Park–Zoo/Adams Morgan" in 1999 to reflect the station's proximity to Adams Morgan. The station was renamed "Woodley Park" with "Zoo/Adams Morgan" as a subtitle in 2011.[11] The southernmost parts of the neighborhood below Rock Creek Park are closer to the Dupont Circle station, while the northeastern parts of the neighborhood are closer to the Columbia Heights Station. In March 2009, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) began operating a DC Circulator bus route connecting the center of Adams Morgan with both Metro stations. The area is also served by a number of WMATA Metrobus lines, including the 42, 43, 90, 92, 96, H1, L2, S2, and S9.

Hospitality

On Connecticut Avenue, at the western edge of the neighborhood, is the Washington Hilton hotel, built in 1965. There are several smaller bed-and-breakfast lodgings in the area. In late 2017, The Line hotel opened at 1770 Euclid Street.

Education

The District of Columbia Public Schools is the public school system. Oyster Adams Bilingual School, the neighborhood K-8 school, was formed in 2007 by the merger of John Quincy Adams Elementary School in Adams Morgan and James F. Oyster Bilingual Elementary School in Woodley Park.[12] The Adams campus serves grades 4-8 and the Oyster campus serves grades Pre-Kindergarten through 3.[13] The Marie Reed Elementary School, with its Learning Center, (built in 1977) was extensively remodeled and reopened in 2017.[14] Also, H.D. Cooke Elementary School is located at 2525 17th Street; it was renovated in 2009 as an environmentally-smart "green" school.

One section is zoned to Oyster-Adams K-8. Another section is zoned to Marie Reed Elementary and Columbia Heights Education Campus, and another is zoned to H.D. Cooke Elementary and Columbia Heights Education Campus.[15][16] All sections are zoned to Woodrow Wilson High School.[17]

City politics

Adams Morgan is a part of Ward 1, and is in the service area of Advisory Neighborhood Commission 1C, the Adams Morgan Advisory Neighborhood Commission. The ANC covers the area between Harvard Street and Rock Creek to the north, Florida Avenue and U Street to the south, 16th Street NW to the east, and Connecticut Avenue to the west.[18]

In popular culture

In Showtime series Homeland Season 3, Episode 4 ("Game On"), the main character Carrie Mathison states that she lives in Adams Morgan.

Scenes from the 2010 movie How Do You Know featuring Paul Rudd and Reese Witherspoon were filmed in Adams Morgan.[19]

The Adams Morgan bar Chief Ike's Mambo Room was a filming location for episodes of the 2003 HBO series K Street produced by George Clooney.

California Representative Gary Condit, suspected at one point in the murder of Chandra Levy, lived on Adams Mill Road in Adams Morgan while he was a congressman and during his affair with the intern.

Writer Nora Ephron and journalist Carl Bernstein lived for many years directly after Watergate in The Ontario Apartments in Adams Morgan, and Ephron wrote her book Heartburn about their time as a married couple in the building.

The neighborhood's competing "jumbo slice" pizza establishments have been covered extensively by local media and an episode of Travel Channel's Food Wars.[20][21]

In Netflix series Taken, the neighborhood is mentioned in season 1, episode 8 where a car bomb blows up.

See also

References

- Adams Morgan DC Neighborhood Guide—Compass.

- Meridian Hill: A History, by Stephen McKevitt (History Press, 2014), pg. 123.

- Kuan, Diana (2007-01-28). "U Street, Adams Morgan humming again". The Boston Globe.

- "Neighborhoods, History & Boundaries of Adams Morgan". Archived from the original on 2013-04-08. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- Smith, Kathryn Schneider (2010). Washington at Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 439. ISBN 9780801893537.

- Stevens, Joann (March 30, 1978). "A Community Center for Adams Morgan". Washington Post. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- Rude, Justin (2012-07-27). "Explore the new Adams Morgan with our neighborhood guide". The Washington Post.

- Adams Morgan Partnership Business Improvement District.

- McAnaney, Patrick (July 10, 2018). "Adams Morgan is losing diversity, but is new development the culprit?". Greater Greater Washington].

- Neibauer, Michael (October 1, 2014). "Pennsylvania Avenue Is A 'Great Street' Indeed, and In Need". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- "Station names updated for new map" (Press release). Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. 2011-11-03. Archived from the original on 2011-11-05. Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- "About Us" (Archive). Oyster Adams Bilingual Elementary School. Retrieved on November 6, 2014.

- Home. Oyster Adams Bilingual School. Retrieved on September 29, 2016.

- "Marie Reed Elementary School Project." District of Columbia Public Schools. Retrieved on October 3, 2016.

- "Elementary Schools Archived 2017-02-12 at the Wayback Machine" (2016-2017 School Year). District of Columbia Public Schools. Retrieved on May 27, 2018.

- "Middle School Boundary Map Archived 2017-02-11 at the Wayback Machine" (2016-2017 School Year). District of Columbia Public Schools. Retrieved on May 27, 2018.

- "High School Boundary Map Archived 2017-01-31 at the Wayback Machine" (2016-2017 School Year). District of Columbia Public Schools. Retrieved on May 27, 2018.

- What is an ANC?

- http://www.jamescalder.com/Street-Scenes/Movie-shoot-in-Adams-Morgan/8673348_mK2nzL/572901986_hdnnVsD#!i=572901986&k=hdnnVsD

- Jamieson, Dave (November 5, 2004). "The Big Cheese". Washington City Paper. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- Jamie R. Liu (April 3, 2010). "Travel Channel's Food Wars Takes on D.C.'s Jumbo Slice". DCist. Gothamist LLC. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adams Morgan. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Adams Morgan. |