Acacia sensu lato

Acacia s.l. (pronounced /əˈkeɪʃə/ or /əˈkeɪsiə/), known commonly as mimosa, acacia, thorntree or wattle,[2] is a polyphyletic genus of shrubs and trees belonging to the subfamily Mimosoideae of the family Fabaceae. It was described by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1773 based on the African species Acacia nilotica. Many non-Australian species tend to be thorny, whereas the majority of Australian acacias are not. All species are pod-bearing, with sap and leaves often bearing large amounts of tannins and condensed tannins that historically found use as pharmaceuticals and preservatives.

| Acacia s.l. | |

|---|---|

| |

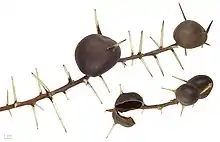

| Senegalia greggii (syn. A. greggii) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Clade: | Mimosoideae |

| Tribe: | Acacieae |

| Genus: | Acacia Mill.[1] |

| Type species | |

| Acacia nilotica (until 2005) Acacia penninervis (post 2005) | |

| Species | |

|

About 1,300; see list of Acacia species | |

The genus Acacia constitutes, in its traditional circumspection, the second largest genus in Fabaceae[3] (Astragalus being the largest), with roughly 1,300 species, about 960 of them native to Australia, with the remainder spread around the tropical to warm-temperate regions of both hemispheres, including Europe, Africa, southern Asia, and the Americas (see List of Acacia species). The genus was divided into five separate genera under the tribe "Acacieae". The genus now called Acacia represents the majority of the Australian species and a few native to southeast Asia, Réunion, and Pacific Islands. Most of the species outside Australia, and a small number of Australian species, are classified into Vachellia and Senegalia. The two final genera, Acaciella and Mariosousa, each contain about a dozen species from the Americas (but see "Classification" below for the ongoing debate concerning their taxonomy).

Classification

English botanist and gardener Philip Miller adopted the name Acacia in 1754. The generic name is derived from ἀκακία (akakia), the name given by early Greek botanist-physician Pedanius Dioscorides (middle to late first century) to the medicinal tree A. nilotica in his book Materia Medica.[4] This name derives from the Ancient Greek word for its characteristic thorns, ἀκίς (akis; "thorn").[5] The species name nilotica was given by Linnaeus from this tree's best-known range along the Nile river. This became the type species of the genus.

The traditional circumscription of Acacia eventually contained approximately 1,300 species. However, evidence began to accumulate that the genus as described was not monophyletic. Queensland botanist Les Pedley proposed the subgenus Phyllodineae be renamed Racosperma and published the binomial names.[6][7] This was taken up in New Zealand but generally not followed in Australia, where botanists declared more study was needed.

Eventually, consensus emerged that Acacia needed to be split as it was not monophyletic. This led to Australian botanists Bruce Maslin and Tony Orchard pushing for the retypification of the genus with an Australian species instead of the original African type species, an exception to traditional rules of priority that required ratification by the International Botanical Congress.[8] That decision has been controversial,[3][9] and debate continued, with some taxonomists (and many other biologists) deciding to continue to use the traditional Acacia sensu lato circumscription of the genus,[8] in defiance of decisions by an International Botanical Congress.[10][11] However, a second International Botanical Congress has now confirmed the decision to apply the name Acacia to the mostly Australian plants, which some had been calling Racosperma, and which had formed the overwhelming majority of Acacia sensu lato.[12][13][14] Debate continues regarding the traditional acacias of Africa, possibly placed in Senegalia and Vachellia, and some of the American species, possibly placed in Acaciella and Mariosousa.

Acacias belong to the subfamily Mimosoideae, the major clades of which may have formed in response to drying trends and fire regimes that accompanied increased seasonality during the late Oligocene to early Miocene (∼25 mya).[15] Pedley (1978), following Vassal (1972), viewed Acacia as comprising three large subgenera, but subsequently (1986) raised the rank of these groups to genera Acacia, Senegalia (s.l.) and Racosperma,[6][7] which was underpinned by later genetic studies.

In common parlance, the term "acacia" is occasionally applied to species of the genus Robinia, which also belongs in the pea family. Robinia pseudoacacia, an American species locally known as black locust, is sometimes called "false acacia" in cultivation in the United Kingdom and throughout Europe.

Description

The leaves of acacias are compound pinnate in general. In some species, however, more especially in the Australian and Pacific Islands species, the leaflets are suppressed, and the leaf-stalks (petioles) become vertically flattened in order to serve the purpose of leaves. These are known as "phyllodes". The vertical orientation of the phyllodes protects them from intense sunlight since with their edges towards the sky and earth they do not intercept light as fully as horizontally placed leaves. A few species (such as Acacia glaucoptera) lack leaves or phyllodes altogether but instead possess cladodes, modified leaf-like photosynthetic stems functioning as leaves.

The small flowers have five very small petals, almost hidden by the long stamens, and are arranged in dense, globular or cylindrical clusters; they are yellow or cream-colored in most species, whitish in some, or even purple (Acacia purpureopetala) or red (Acacia leprosa 'Scarlet Blaze'). Acacia flowers can be distinguished from those of a large related genus, Albizia, by their stamens, which are not joined at the base. Also, unlike individual Mimosa flowers, those of Acacia have more than ten stamens.[16]

The plants often bear spines, especially those species growing in arid regions. These sometimes represent branches that have become short, hard, and pungent, though they sometimes represent leaf-stipules. Acacia armata is the kangaroo-thorn of Australia, and Acacia erioloba (syn. Acacia eriolobata) is the camelthorn of Africa.

Acacia seeds can be difficult to germinate. Research has found that immersing the seeds in various temperatures (usually around 80 °C (176 °F)) and manual seed coat chipping can improve growth to around 80%.[17]

Symbiosis

In the Central American bullthorn acacias—Acacia sphaerocephala, Acacia cornigera and Acacia collinsii — some of the spiny stipules are large, swollen and hollow. These afford shelter for several species of Pseudomyrmex ants, which feed on extrafloral nectaries on the leaf-stalk and small lipid-rich food-bodies at the tips of the leaflets called Beltian bodies. In return, the ants add protection to the plant against herbivores.[18] Some species of ants will also remove competing plants around the acacia, cutting off the offending plants' leaves with their jaws and ultimately killing them. Other associated ant species appear to do nothing to benefit their hosts.

Similar mutualisms with ants occur on Acacia trees in Africa, such as the whistling thorn acacia. The acacias provide shelter for ants in similar swollen stipules and nectar in extrafloral nectaries for their symbiotic ants, such as Crematogaster mimosae. In turn, the ants protect the plant by attacking large mammalian herbivores and stem-boring beetles that damage the plant.[19]

The predominantly herbivorous spider Bagheera kiplingi, which is found in Central America and Mexico, feeds on nubs at the tips of the acacia leaves, known as Beltian bodies, which contain high concentrations of protein. These nubs are produced by the acacia as part of a symbiotic relationship with certain species of ant, which also eat them.[20]

Pests

In Australia, Acacia species are sometimes used as food plants by the larvae of hepialid moths of the genus Aenetus including A. ligniveren. These burrow horizontally into the trunk then vertically down. Other Lepidoptera larvae which have been recorded feeding on Acacia include brown-tail, Endoclita malabaricus and turnip moth. The leaf-mining larvae of some bucculatricid moths also feed on Acacia; Bucculatrix agilis feeds exclusively on Acacia horrida and Bucculatrix flexuosa feeds exclusively on Acacia nilotica.

Acacias contain a number of organic compounds that defend them from pests and grazing animals.[21]

Uses

Use as human food

Acacia seeds are often used for food and a variety of other products.

In Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, the feathery shoots of Acacia pennata (common name cha-om, ชะอม and su pout ywet in Burmese) are used in soups, curries, omelettes, and stir-fries.

Gum

Various species of acacia yield gum. True gum arabic is the product of Acacia senegal, abundant in dry tropical West Africa from Senegal to northern Nigeria.

Acacia nilotica (syn. Acacia arabica) is the gum arabic tree of India, but yields a gum inferior to the true gum arabic. Gum arabic is used in a wide variety of food products, including some soft drinks[22] and confections.

The ancient Egyptians used acacia gum in paints.[23]

The gum of Acacia xanthophloea and Acacia karroo has a high sugar content and is sought out by the lesser bushbaby. Acacia karroo gum was once used for making confectionery and traded under the name "Cape Gum". It was also used medicinally to treat cattle suffering poisoning by Moraea species.[24]

Uses in folk medicine

Acacia species have possible uses in folk medicine. A 19th-century Ethiopian medical text describes a potion made from an Ethiopian species (known as grar) mixed with the root of the tacha, then boiled, as a cure for rabies.[25]

An astringent medicine high in tannins, called catechu or cutch, is procured from several species, but more especially from Senegalia catechu (syn. Acacia catechu), by boiling down the wood and evaporating the solution so as to get an extract.[26][27] The catechu extract from A. catechu figures in the history of chemistry in giving its name to the catechin, catechol, and catecholamine chemical families ultimately derived from it.

Ornamental uses

A few species are widely grown as ornamentals in gardens; the most popular perhaps is A. dealbata (silver wattle), with its attractive glaucous to silvery leaves and bright yellow flowers; it is erroneously known as "mimosa" in some areas where it is cultivated, through confusion with the related genus Mimosa.

Another ornamental acacia is the fever tree. Southern European florists use A. baileyana, A. dealbata, A. pycnantha and A. retinodes as cut flowers and the common name there for them is mimosa.[28]

Ornamental species of acacias are also used by homeowners and landscape architects for home security. The sharp thorns of some species are a deterrent to trespassing, and may prevent break-ins if planted under windows and near drainpipes. The aesthetic characteristics of acacia plants, in conjunction with their home security qualities, makes them a reasonable alternative to constructed fences and walls.

Perfume

Acacia farnesiana is used in the perfume industry due to its strong fragrance. The use of acacia as a fragrance dates back centuries.

Symbolism and ritual

Egyptian mythology has associated the acacia tree with characteristics of the tree of life, such as in the Myth of Osiris and Isis.

Several parts (mainly bark, root, and resin) of Acacia species are used to make incense for rituals. Acacia is used in incense mainly in India, Nepal, and China including in its Tibet region. Smoke from acacia bark is thought to keep demons and ghosts away and to put the gods in a good mood. Roots and resin from acacia are combined with rhododendron, acorus, cytisus, salvia, and some other components of incense. Both people and elephants like an alcoholic beverage made from acacia fruit.[29] According to Easton's Bible Dictionary, the acacia tree may be the “burning bush” (Exodus 3:2) which Moses encountered in the desert.[30] Also, when God gave Moses the instructions for building the Tabernacle, he said to "make an ark" and "a table of acacia wood" (Exodus 25:10 & 23, Revised Standard Version). Also, in the Christian tradition, Christ's crown of thorns is thought to have been woven from acacia.[31]

Acacia was used for Zulu warriors' iziQu (or isiKu) beads, which passed on through Robert Baden-Powell to the Scout movement's Wood Badge training award.[32]

In Russia, Italy, and other countries, it is customary to present women with yellow mimosas (among other flowers) on International Women's Day (March 8). These "mimosas" may be from A. dealbata (silver wattle).

In 1918, May Gibbs, the popular Australian children's author, wrote the book 'Wattle Babies', in which a third-person narrator describes the lives of imaginary inhabitants of the Australian forests (the 'bush'). The main characters are the Wattle Babies, who are tiny people that look like acacia flowers and who interact with various forest creatures. Gibbs wrote "Wattle Babies are the sunshine of the Bush. In Winter, when the sky is grey and all the world seems cold, they put on their yellowest clothes and come out, for they have such cheerful hearts."[33] Gibbs was referring to the fact that an abundance of acacias flower in August in Australia, in the midst of the southern hemisphere winter.[34]

Tannin

The bark of various Australian species, known as wattles, is very rich in tannin and forms an important article of export; important species include A. pycnantha (golden wattle), A. decurrens (tan wattle), A. dealbata (silver wattle) and A. mearnsii (black wattle).

Black wattle is grown in plantations in South Africa and South America. Most Australian Acacia species introduced to South Africa have become an enormous problem, due to their naturally aggressive propagation. The pods of A. nilotica (under the name of neb-neb), and of other African species, are also rich in tannin and used by tanners. In Yemen, the principal tannin substance was derived from the leaves of the salam-tree (Acacia etbaica), a tree known locally by the name qaraẓ (garadh).[35][36] A bath solution of the crushed leaves of this tree, into which raw leather had been inserted for prolonged soaking, would take only 15 days for curing. The water and leaves, however, required changing after seven or eight days, and the leather needed to be turned over daily.

Wood

Some Acacia species are valuable as timber, such as A. melanoxylon (blackwood) from Australia, which attains a great size; its wood is used for furniture, and takes a high polish; and A. omalophylla (myall wood, also Australian), which yields a fragrant timber used for ornaments. A. seyal is thought to be the shittah-tree of the Bible, which supplied shittim-wood. According to the Book of Exodus, this was used in the construction of the Ark of the Covenant. A. koa from the Hawaiian Islands and A. heterophylla from Réunion are both excellent timber trees. Depending on abundance and regional culture, some Acacia species (e.g. A. fumosa) are traditionally used locally as firewoods.[37] It is also used to make homes for different animals.

Pulpwood

In Indonesia (mainly in Sumatra) and in Malaysia (mainly in Sabah), plantations of A. mangium are being established to supply pulpwood to the paper industry.

Acacia wood pulp gives high opacity and below average bulk paper. This is suitable in lightweight offset papers used for Bibles and dictionaries. It is also used in paper tissue where it improves softness.

Land reclamation

Acacias can be planted for erosion control, especially after mining or construction damage.[38]

Ecological invasion

For the same reasons it is favored as an erosion-control plant, with its easy spreading and resilience, some varieties of acacia are potentially invasive species. One of the most globally significant invasive acacias is black wattle A. mearnsii, which is taking over grasslands and abandoned agricultural areas worldwide, especially in moderate coastal and island regions where mild climate promotes its spread. Australian/New Zealand Weed Risk Assessment gives it a "high risk, score of 15" rating and it is considered one of the world's 100 most invasive species.[39] Extensive ecological studies should be performed before further introduction of acacia varieties, as this fast-growing genus, once introduced, spreads quickly and is extremely difficult to eradicate.

Phytochemistry

Cyanogenic glycosides

Nineteen different species of Acacia in the Americas contain cyanogenic glycosides, which, if exposed to an enzyme which specifically splits glycosides, can release hydrogen cyanide (HCN) in the "leaves".[40] This sometimes results in the poisoning death of livestock.

If fresh plant material spontaneously produces 200 ppm or more HCN, then it is potentially toxic. This corresponds to about 7.5 μmol HCN per gram of fresh plant material. It turns out that, if acacia "leaves" lack the specific glycoside-splitting enzyme, then they may be less toxic than otherwise, even those containing significant quantities of cyanic glycosides.[41]

Some Acacia species containing cyanogens include Acacia erioloba, A. cunninghamii, A. obtusifolia, A. sieberiana, and A. sieberiana var. woodii[42]

Famous acacias

The Arbre du Ténéré in Niger was the most isolated tree in the world, about 400 km (249 mi) from any other tree. The tree was knocked down by a truck driver in 1973.[43]

In Nairobi, Kenya, the Thorn Tree Café is named after a Naivasha thorn tree (Acacia xanthophloea)[44] in its centre. Travelers used to pin notes to others to the thorns of the tree. The current tree is the third of the same variety.

References

- Genus: Acacia Mill. – Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN)

- Carruthers, Jane; Robin, Libby (February 2010). "Taxonomic imperialism in the battles for Acacia: Identity and science in South Africa and Australia". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa. 65 (1): 48–64. doi:10.1080/00359191003652066. S2CID 83630585.

- Thiele, Kevin R.; Fnk, Vicki A.; Iwatsuki, Kunio; Morat, Philippe; Peng, Ching-I; Raven, Peter; Sarukhán, José; Seberg, Ole (February 2011). "The controversy over the retypification of Acacia Mill. with an Australian type: A pragmatic view" (PDF). Taxon. 60 (1): 194–198. doi:10.1002/tax.601017. ISSN 0040-0262. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- "Acacia nilotica (acacia)". Plants & Fungi. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 2010-01-12. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- Quattrocchi, Umberto (2000). CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names. 1 A-C. CRC Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8493-2675-2.

- Maslin, Bruce R. (2004). Classification and phylogeny of Acacia. In: Evolution of ecological and behavioural diversity: Australian Acacia thrips as model organisms. Australian Biological Resources Study and Australian National Insect Collection, CSIRO. pp. 97–112. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Boland, D. J. (2006). Forest trees of Australia (5th ed.). Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publ. [u.a.] p. 127. ISBN 978-0-643-06969-5.

- Gideon F. Smith; Estrela Figueiredo (2011). "Conserving Acacia Mill. with a conserved type: What happened in Melbourne?". Taxon. 60 (5): 1504–1506. doi:10.1002/tax.605033. hdl:2263/17733.

- Christian Kull; Haripriya Rangan (2012). "Science, sentiment and territorial chauvinism in the acacia name change debate" (PDF). Terra Australis. 34: 197–219. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- Anders Backlund; Kåre Bremer (1998). "To be or not to be – principles of classification and monotypic plant families". Taxon. 47 (2): 391–400. doi:10.2307/1223768. JSTOR 1223768.

- Anastasia Thanukos (2009). "A name by any other tree". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 2 (2): 303–309. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0122-7.

- "Wattles – genus Acacia". Australian National Herbarium. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- "The Acacia debate" (PDF). IBC2011 Congress News. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- "Conserving Acacia Mill. with a conserved type: What happened in Melbourne?". Taxon. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- Bouchenak-Khelladi, Yanis; Maurin, Olivier; Hurter, Johan; van der Bank, Michelle (November 2010). "The evolutionary history and biogeography of Mimosoideae (Leguminosae): An emphasis on African acacias". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 57 (2): 495–508. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.07.019. PMID 20696261.

- Singh, Gurcharan (2004). Plant Systematics: An Integrated Approach. Science Publishers. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-57808-351-0.

- J Clemens; PG Jones; NH Gilbert (1977). "Effect of seed treatments on germination in Acacia". Australian Journal of Botany. 25 (3): 269–276. doi:10.1071/BT9770269.

- Martin Heil; Sabine Greiner; Harald Meimberg; Ralf Krüger; Jean-Louis Noyer; Günther Heubl; K. Eduard Linsenmair; Wilhelm Boland (2004). "Evolutionary change from induced to constitutive expression of an indirect plant resistance". Nature. 430 (6996): 205–208. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..205H. doi:10.1038/nature02703. PMID 15241414. S2CID 4416036.

- Palmer, T.M.; M.L. Stanton; T.P. Young; J.R. Goheen; R.M Pringle; R. Karban (January 2008). "Breakdown of an ant-plant mutualism following the loss of large herbivores from an African savanna". Science. 319 (5860): 192–195. Bibcode:2008Sci...319..192P. doi:10.1126/science.1151579. PMID 18187652. S2CID 32467164.

- Meehan, Christopher J.; Olson, Eric J.; Curry, Robert L. (21 August 2008): Exploitation of the Pseudomyrmex–Acacia mutualism by a predominantly vegetarian jumping spider (Bagheera kiplingi). The 93rd ESA Annual Meeting.

- T. D. A. Forbes; B. A. Clement. "Chemistry of Acacia's from South Texas" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- "Powerade Ion4 Sports Drink, B Vitamin Enhanced, Strawberry Lemonade". Wegmans. Archived from the original on 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- "Excerpt from A Consumer's Dictionary of Cosmetic Ingredients: Fifth Edition (Paperback) Amazon.com". Amazon.ca. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- "Vachellia karroo | PlantZAfrica.com".

- Richard Pankhurst, An Introduction to the Medical History of Ethiopia (Trenton: Red Sea Press, 1990), p. 97

- "An OCR'd version of the US Dispensatory by Remington and Wood, 1918". Henriettesherbal.com. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- "Cutch and catechu plant origin from the Food and Agriculture (FAO) department of the United Nations. Document repository accessed November 5, 2011".

- "World Wide Wattle". World Wide Wattle. 2009-09-07. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Naturheilpraxis Fachforum (German)

- "Easton's Bible Dictionary: Bush". Eastonsbibledictionary.com. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Dictionary of Symbols.Chevalier and Gheerbrant. Penguin Reference.1996.

- "The Origins of the Wood Badge" (PDF). The Scout Association. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "May Gibbs' 'Wattle Babies'". Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Costermans, Leon F. (1981). Native Trees and Shrubs of South-Eastern Australia: Includes Ammendum of Change and New Species. Adelaide, South Australia: Rigby. ISBN 0727017993.

- R. Moss b. Maimon RESPONSA (ed. Jehoshua Blau), vol. 2, responsum # 253, Rubin Mass Ltd.: Jerusalem 1989, p. 298 (s.v. Judeo-Arabic original, אלקרץ).

- James P. Mandaville, Bedouin Ethnobotany – Plant Concepts and Uses in a Desert Pastoral World, University of Arizona Press 2011, p. 140 (ISBN 978-0-8165-2900-1)

- Maugh, T.H. II (2009-04-24). "New species of tree identified in Ethiopia". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- Barr, D. A.; Atkinson, W. J. (1970). "Stabilization of coastal sands after mining". J. Soil Conserv. Serv. N.S.W. 26: 89–105.

- "Acacia mearnsii (PIER species info)". Hear.org. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Seigler, David S. (1987). "Cyanogenic Glycosides in Ant-Acacias of Mexico and Central America". The Southwestern Naturalist. 32 (4): 499–503. doi:10.2307/3671484. JSTOR 3671484.

- Hegnauer, R. (1996-01-01). Chemotaxonomie der Pflanzen By Robert Hegnauer. ISBN 9783764351656. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- FAO Kamal M. Ibrahim, The current state of knowledge on Prosopis juliflora... Archived October 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Michael Palin, Sahara, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-2978-6359-5

- Jan Hemsing (1974). Old Nairobi and the New Stanley Hotel. Church, Raitt, and Associates. p. 53.

Further reading

- Clement, B.A.; Goff, C.M.; Forbes, T.D.A. (1998). "Toxic Amines and Alkaloids from Acacia rigidula". Phytochemistry. 49 (5): 1377–1380. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(97)01022-4.

- Schindler, Jason R.; Fulbright, Timothy E.; Forbes, T.D.A (2004), "Long-term effects of roller chopping on antiherbivore defenses in three shrub species", Journal of Arid Environments, 56 (1): 181–192, Bibcode:2004JArEn..56..181S, doi:10.1016/S0140-1963(03)00020-X

- Shulgin, Alexander and Ann, TiHKAL the Continuation. Transform Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-9630096-9-2

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Acacia. |

- World Wide Wattle

- Acacia-world

- Wayne's Word on "The Unforgettable Acacias"

- The genus Acacia and Entheogenic Tryptamines, with reference to Australian and related species, by mulga

- A description of Acacia from Pomet's 1709 reference book, History of Druggs

- Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases

- Flora identification tools from the State Herbarium of South Australia

- Tannins in Some Interrelated Wattles

- List of Acacia Species in the U.S.

- FAO Timber Properties of Various Acacia Species

- FAO Comparison of Various Acacia Species as Forage

- Vet. Path. ResultsAFIP Wednesday Slide Conference – No. 21 February 24, 1999

- Acacia cyanophylla lindl as supplementary feed/for small stock in Libya

- Description of Acacia Morphology

- Nitrogen Fixation in Acacias

- Acacias with Cyagenic Compounds

- Acacia Alarm System

- Acacia in West African plants – A Photo Guide.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.