Abrams v. United States

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States upholding the 1918 Amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917, which made it a criminal offense to urge the curtailment of production of the materials necessary to wage the war against Germany with intent to hinder the progress of the war. The 1918 Amendment is commonly referred to as if it were a separate Act, the Sedition Act of 1918.

| Abrams v. United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued October 21–22, 1919 Decided November 10, 1919 | |

| Full case name | Jacob Abrams, et al. v. United States |

| Citations | 250 U.S. 616 (more) 40 S. Ct. 17; 63 L. Ed. 1173; 1919 U.S. LEXIS 1784 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Defendants convicted, U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York |

| Subsequent | None |

| Holding | |

| Defendants' criticism of U.S. involvement in World War I was not protected by the First Amendment, because they advocated a strike in munitions production and the violent overthrow of the government. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

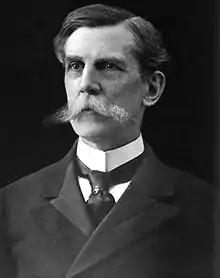

| Majority | Clarke, joined by White, McKenna, Day, Van Devanter, Pitney, McReynolds |

| Dissent | Holmes, joined by Brandeis |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. I; 50 U.S.C. § 33 (1917) | |

The defendants were convicted on the basis of two leaflets they printed and threw from windows of a building in New York City. One leaflet, signed "revolutionists", denounced the sending of American troops to Russia. The second leaflet, written in Yiddish, denounced the war and US efforts to impede the Russian Revolution. It advocated the cessation of the production of weapons to be used against Soviet Russia.

The defendants were charged and convicted of inciting resistance to the war effort and urging curtailment of production of essential war material. They were sentenced to 10 and 20 years in prison. The Supreme Court ruled, 7–2, that the defendants' freedom of speech, protected by the First Amendment, was not violated.[1] Justice John Hessin Clarke in an opinion for the majority held that the defendants' intent to hinder war production could be inferred from their words, and that Congress had determined such expressions posed an imminent danger. Their conviction was accordingly warranted under the "clear-and-present-danger" standard, derived from the common law and announced in Schenck v. United States and companion cases earlier in 1919. Opinions for a unanimous Court in those cases were written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. In the Abrams case, however, Holmes dissented, rejecting the argument that the defendants' leaflets posed the "clear and present danger" that was true of the defendants in Schenck. In a powerful dissenting opinion joined by Justice Louis Brandeis, he said that the Abrams defendants lacked the specific intent to interfere with the war against Germany, and that they posed no actual risk. He went on to say that even if their acts could be shown to pose a risk of damaging war production, the draconian sentences imposed showed that they were being prosecuted not for their speech, but for their beliefs.

Background of the case

On August 12, 1919, Hyman Rosansky was arrested after throwing flyers out of a 4th-floor window of a hat factory located near the corner of Houston and Crosby, in lower Manhattan, New York.[2] Rosanky had received the flyers the night before while attending an anarchist meeting. Two different flyers were given to him, one in English, the other in Yiddish. The flyers were an acerbic protest against the Woodrow Wilson administration for interfering with the Russian Revolution in support of the Russian government. The flyers had been printed on or about June 15, 1919, in a basement rented by Jacob Abrams located at 1582 Madison Avenue. With Rosansky's help, police arrested six other Russian Jews: Mollie Steimer, Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky, Jacob Schwartz, Gabriel Prober, and Samuel Lipman. All had emigrated from Russia to the United States.[3]

The defendants were indicted for conspiring to violate the Espionage Act of 1917. Although trial had begun on October 10, 1919, actual trial proceedings were set to commence on October 15, 1919. On October 14, Jacob Schwartz died at Bellevue Hospital. The official cause of death was that he succumbed to the Spanish flu.

The trial concluded on October 23, 1919, resulting in the following dispositions; (1) Gabriel Prober was acquitted, (2) Hyman Rosansky was convicted and sentenced to 3 years, (3) Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky, and Samuel Lipman were convicted and sentenced to 20 years and a $1,000 fine, and (4) Mollie Steimer was convicted and sentenced to 15 years and a $5,000 fine. The defendants appealed their convictions to the United States Supreme Court.

Majority opinion

Writing for the majority, Justice John Hessin Clarke asserted that the leaflets demonstrated an intent to hinder production of war material, and could not be characterized as simple expressions of political opinion. Quoting English translations of a leaflet written in Yiddish, Clark concluded:

This is not an attempt to bring about a change of administration by candid discussion, for no matter what may have incited the outbreak on the part of the defendant anarchists, the manifest purpose of such a publication was to create an attempt to defeat the war plans of the government of the United States, by bringing upon the country the paralysis of a general strike, thereby arresting the production of all munitions and other things essential to the conduct of the war.[4]

In answer to the claim that the defendants were concerned only with United States' intervention in Russia, he asserted that the leaflets

sufficiently show, that while the immediate occasion for this particular outbreak of lawlessness, on the part of the defendant alien anarchists, may have been resentment caused by our government giving troops into Russia as a strategic operation against the Germans on the eastern battle front, yet the plain purpose of their propaganda was to excite, at the supreme crisis of the war, disaffection, sedition, riots, and, as they hoped, revolution, in this country for the purpose of embarrassing and if possible defeating the military plans of the government in Europe.[5]

The Court held that the leaflets' call for a general strike and the curtailment of munitions production violated the Sedition Act of 1918. Congress' determination that all such propaganda posed a danger to the war effort was sufficient to meet the standard set in Schenck v. United States for prosecution of attempted crimes, when the attempt was made through speech or writing. Holmes' argument, in dissent, that criminal prosecution required a showing of the specific intent to bring about the particular harm at which the statute was aimed, was rejected.

Holmes's dissent

In his dissent, Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that although the defendant's pamphlet called for a cessation of weapons production, it had not violated the Act of May 16, 1918. He wrote that the defendants did not have the requisite intent "to cripple or hinder the United States in the prosecution of the war" against Germany. The defendants were objecting only to the United States intervention in the Russian civil war. The defendants therefore lacked the specific intent to commit the crime of obstructing the war effort.[6]

Holmes's three earlier opinions for a unanimous Supreme Court concerned convictions under the 1918 Sedition Act, in the first of which, Schenck v. United States, he stated the famous "clear and present danger" standard: speech could be punished if it posed a clear and present danger of causing some harm that Congress had power to forbid.[7] The defendants in Schenck had mailed leaflets to men awaiting induction, urging them to resist the draft. The defendants did not deny that they intended this result. Since they could have been prosecuted for a crime if they accomplished the intended result, and there was a clear and present danger that they would, they could also be convicted of an attempt to commit the crime of obstructing the draft. The statute only applied to successful obstructions, but common-law precedents allowed prosecution in this case for an attempt. In his opinion, Holmes relied on the common law of "attempts," and concluded without much discussion that an attempt might be made by words as by other means, the First Amendment notwithstanding.

In his Abrams dissent, Holmes explained why some speech was protected by the Constitution, an explanation that was not called for in the earlier cases. His opinion for the Court in Schenck had been criticized by a scholar, Zechariah Chafee, who said the Court had explained only that attempts to commit crimes could be prosecuted. Holmes had young friends, Jewish immigrants who had themselves been attacked for their left-wing opinions, and he therefore may have felt more strongly about this case than its predecessors. In his dissent he now explained his views more fully. He did insist that the majority had departed from the standard adopted by a unanimous court that same year, since the Abrams defendants neither intended the forbidden result nor did their leaflets, written in Yiddish, threaten to cause a forbidden result. Holmes's dissent is now accepted as the better statement of the standard, but the Court's ruling that legislation could criminalize all seditious speech has also been upheld.[8]

Holmes's passionate, indignant opinion is often quoted:

Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition...But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas... . The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out,[9][10]

Holmes expressed himself more fully in this dissent than in his earlier opinions for a unanimous Court concerning the value of free expression, and the reasons for which it might be regulated. In his Abrams dissent, he added this explanation of his dissent. He had not asked the Court as a whole to endorse this larger expression in the earlier cases.

Scholars have debated whether Holmes altered his views over the course of the weeks between the two sets of opinions.[11] Holmes always maintained that he had adhered to the standard for punishing criminal attempts used in the earlier convictions, a standard based on long years as a common-law judge and scholar.[12] Critics of his earlier "clear-and-present-danger" opinion have insisted that the Abrams dissent stands on a different footing, and is more protective. The objection may be based in part on a misunderstanding. In his Abrams dissent, Holmes first disposed of the argument that the facts in the case supported a conviction under the clear-and-present-danger standard, insisting that a criminal prosecution required proof of specific intent to commit the crime that was charged. He then went on to say, however, that even if the defendants' speech could be punished as an attempted crime, even if "enough can be squeezed from these poor and puny anonymities to turn the color of legal litmus paper," the sentences of ten and twenty years, followed by deportation, showed that Abrams and his friends were prosecuted, not for their dangerous attempts, but for their beliefs. Holmes went on to challenge, not the Court's conclusion, but the Wilson Administration's prosecution of these defendants as an outrageous abuse of power. The "marketplace of ideas" Holmes insisted is the foundation of the constitutional system, not merely the First Amendment, and efforts to suppress opinions by force therefore contradict a fundamental principle of the Constitution.

Holmes's friends and colleagues generally supported the decision in Schenck, but he encountered mild criticism from a young judge, Learned Hand, who had ruled differently in a similar case. In an article Zechariah Chafee complained that Holmes had failed in his opinions for the Court to define the contours of the privilege accorded to speech, holding only that criminal speech could be prosecuted. In his Abrams dissent, Holmes expanded his statement of the privilege accorded to honest expressions of opinions, on much the lines that Chafee had recommended, extending the analysis made in Schenck. Scholars have claimed that Holmes was influenced by Chafee and Hand, by Brandeis, or by others. These claims are stated in numerous articles, and summarized in a book by Richard Polenberg.[13] In 1989 Sheldon Novick's first full biography of Holmes suggested that the justice had been consistent in his decisions, as he claimed to have been.[14] Building on the argument that Holmes changed his mind, scholars have claimed not only that the dissent in Abrams expressed a different and more liberal understanding of the First Amendment, but that the Abrams dissent set the standard for modern First Amendment jurisprudence.[15] The Supreme Court has rejected this view, however.

Subsequent jurisprudence

The Abrams case has been kept alive by the scholarly dispute, but in recent years the Supreme Court has not cited either the majority opinion or Holmes' dissent as authority. The World War I sedition cases were overshadowed by new prosecutions under new statutes in World War II, the Cold War, the Vietnam War and the War on Terror. Learned Hand, a judge of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, contributed to the modern dislike of the "clear-and-present-danger" formula by citing it in an opinion upholding the convictions of the leaders of the Communist Party;[16] his opinion was upheld by a bitterly divided Supreme Court in Dennis v. United States (1951),[17] and the Supreme Court subsequently avoided use of that phrase, replacing it with a similar formula in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1968), holding that speech can only be prosecuted as an attempt if it is intended to produce "imminent lawless action".[18]

More recently, the Court has expressly rejected the reasoning of Holmes' Abrams dissent in two decisions. In Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (2010) the facts were similar to those in Abrams. Respondents had offered advice and other verbal assistance to organizations fighting established governments in Sri Lanka and Turkey, organizations that had been designated as terrorists, and were subject to prosecution for attempting to provide material support to terrorist organizations in violation of what is now the USA PATRIOT Act, section 2339B. The respondents argued, supported by three dissenting justices, that they lacked the specific intent to aid in terrorist acts, and therefore could not be prosecuted for a criminal attempt. The majority rejected this argument, however, and repeated without citing the majority opinion in Abrams, that Congress had the power to determine that all such expressive conduct posed a threat to national security.[19]

In the same year, in Citizens United v. FEC dissenting judges made Holmes's argument that the Constitution broadly protects the "marketplace of ideas", but the majority opinion brushed this aside, saying that freedom of expression was an individual right, not rooted in community interests, possessed by artificial as well as natural persons.[20] As the law now stands, it appears that neither the majority opinion in Abrams, with its reliance on the clear-and-present-danger formula, nor Holmes's dissent, are authoritative, and while Schenck appears to remain good law, it is now more common to cite Brandenburg v. Ohio for the standard to be applied in criminal prosecutions, except in cases involving national security in which Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project governs.

See also

- Clear and present danger

- Imminent lawless action

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 250

- Shouting fire in a crowded theater

- Threatening the President of the United States

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969)

- Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942)

- Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951)

- Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951)

- Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105 (1973)

- Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)

- Kunz v. New York, 340 U.S. 290 (1951)

- Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten, (1917)

- Sacher v. United States, 343 U.S. 1 (1952)

- Schenck v. United States, 248 U.S. 47 (1919)

- Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949)

- Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927)

References

- Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919).

- Szajkowsky, Z. (1971) Double Jeopardy - The Abrams Case of 1919. The American Jewish Archives XXIII(1), 6-32.

- Polenberg, R. (1987), Fighting Faiths: The Abrams Case, the Supreme Court, and Free Speech. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Abrams, 250 U.S. at 622.

- Abrams, 250 U.S. at 623.

- Abrams, 250 U.S. at 626.

- Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919).

- Thomas Healey, The Great Dissent: How Holmes Changed His Mind--and Changed the History of Freedom of Speech in America, 2013

- Abrams, 250 U.S. at 630.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., and Paul Finkelman, "Abrams v. United States (1919)." Documents of American Constitutional and Legal History, third ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 666–667.

- Albert J. Alschuler, Law Without Values (2000) pp.71-72.

- Sheldon M. Novick, "The Unrevised Holmes and Freedom of Expression," 1991 The Supreme Court Review, p. 303 (1992)

- Richard Polenberg, Fighting Faiths: The Abrams Case, the Supreme Court, and Free Speech, pp. 218–228 (1987)

- Sheldon Novick, "Preface: Honorable Justice at Twenty-Five," in Honorable Justice: The Life of Oliver Wendell Holmes (1989, 2013).

- Thomas Healey, The Great Dissent, supra and sources cited there

- United States v. Dennis, 183 F.2d 201 (2d. Cir. 1950).

- Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951).

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1968).

- Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, 561 U.S. 1 (2010).

- Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310 (2010).

Further reading

- Chafee, Zechariah (June 1919). "Freedom of Speech in Wartime". Harvard Law Review. 32 (8): 932–973. doi:10.2307/1327107. JSTOR 1327107.

- Polenberg, Richard (1999). Fighting Faiths: The Abrams Case, the Supreme Court, and Free Speech. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8618-0.

- Pollock, S. F. (1920). "Abrams v. United States". Law Quarterly Review. 36: 334. ISSN 0023-933X.

- Smith, Stephen A. (2003). "Schenck v. United States and Abrams v. United States". In Parker, Richard A. (ed.). Free Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives on Landmark Supreme Court Decisions. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. pp. 20–35. ISBN 978-0-8173-1301-2.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Text of Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)

- Case brief: Quimbee

- First Amendment Library entry for Abrams v. United States