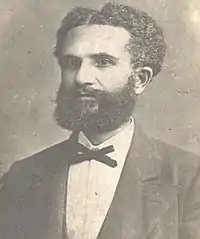

Abdyl Frashëri

Abdyl Dume bey Frashëri (Turkish: Fraşerli Abdül Bey; 1 June 1839 – 23 October 1892) was an Ottoman Albanian civil servant, politician of the Ottoman Empire and one of the first Albanian political ideologues of the Albanian National Awakening.[2] During his lifetime Frashëri endeavoured to instill among Albanians patriotism and a strong identity while promoting a reform program based on Albanian language education and literature.[3]

Abdyl Frashëri | |

|---|---|

Abdyl Frashëri | |

| Born | |

| Died | 23 October 1892 (aged 53) |

| Other names | Abdullah Hysni Frashëri |

| Organization | Central Committee for Defending Albanian Rights League of Prizren Assembly of Preveza Albanian Committee of Janina |

| Movement | Albanian Vilayet National Renaissance of Albania |

| Spouse(s) | Ballkëze Frashëri |

| Children | Mid’hat Frashëri,[1] Feridun Frashëri, Halid Frashëri |

| Relatives | Naim Frashëri (brother) Sami Frashëri (brother) Mehdi Frashëri (nephew) Ali Sami Yen (nephew) |

| Awards | |

He was one of the initiators and a prominent leader of the League of Prizren. He distinguished himself as a political personality from the 1860s through early political assignments. He founded the Central Committee for Defending Albanian Rights in Istanbul. He furthermore served as a chosen representative for the Yanya Vilayet in the Ottoman Parliament during the First Constitutional Era, 1876–1877.[4] During the communist regime he was proclaimed with the honour Hero of Albania.

Early life

Abdyl Frashëri was born in 1839 in the village of Frashër in the Vilayet of Janina to a distinguished Muslim Albanian family of Bektashi religious affiliations.[5] Abdyl, alongside his brothers Naim, Sami and 5 other siblings were the children of Halit Bey (1797–1859)[6] and their paternal family traditions held that they were descendants of timar holders that hailed from the Berat region before coming to live in Frashër.[5] While their mother Emine Hanım (1814–1861)[6] was descended from Imrahor Ilyas Bey, a distinguished 15th century Ottoman Albanian commander from the Korçë area.[5]

Being the eldest brother of Naim Frashëri and Sami Frashëri, Abdyl Frashëri spent his youth to age 18 in his home village and eventually moved to Yannina where he lived for more than 20 years. His father, Halit Bey Frashëri, was a Tosk Albanian bey and commander of an irregular army, composed of Albanian militia contingents. His military service was to bring order to the unsettled territories of the Rumelia province, mainly inside Albanian-inhabited territories. He saw duty in areas such as Toskëria, Gegëria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, Thessaly and Macedonia with the last two often on the verge of uprisings by Greek rebels. During these expeditions, Abdyl was part of his father's military contingent and served as a captain of the Albanian forces.

His father died in 1859 and so Abdyl became the head of the household, as his five brothers and two sisters were all younger than him. After two years, as his mother died Frashëri became head of the household and moved the family to Ioannina.[5] He was posted as a clerk and governor of the Ioannina house, along with his two younger brothers. He dedicated himself to his studies, and worked with scholars in Ioanina, in particular with the notable Albanian müderris Hasan Tahsini from whom he learned Arabic, Persian, French, and Greek. Frashëri also studied science, philosophy and math. After he had finished the studies, he became engaged and married Ballkëze, the daughter of myfti Ibrahim Frashëri from the Lahçenja family and Xhenfize Çoku the family of Çokollarëve, who were also known as Aliçkas. Ballkëz, Frashëri's wife, bore six children. The first son was born in 1874 and was given the name of his grandfather, Halit. The child died in infancy. The second son, born in 1876, was also named Halit, and also died young, as did the two later sons, both named Feridun. Of all the children, five sons and one daughter, born to Frashëri and Ballkëz, only their third son, Mit’hat Frashëri and their daughter lived. She was named after Frashëri's mother, Emine.

Political activity

Work for the Autonomy of Albania (1860s-late 1870s)

Abdul Frashëri distinguished himself as a prominent Albanian statesman and political personality in the early 1860s. He was the member for Yanina in the first Ottoman Parliament.[7] Frashëri was outspoken on issues relating to his Albanian constituency.[7] In a parliamentary speech on 14 January 1878 he criticised a lack of "progress" and blamed it on "despotism", "ignorance", and incompetent bureaucrats with a call for widespread education in the empire to remedy the situation.[7] Coming under criticism from other Ottoman parliamentarians Abdul also expressed sentiments of having pride in being Ottoman, an identity that linked him to medieval Arab-Islamic civilisation.[7] He was founding member of the Society for the Publication of Albanian Writings (1879) that promoted Albanian language publications.[8] However, when the Russo-Turkish War of (1877–1878) resulted in Ottoman defeat, the integrity of the Ottoman Empire and that of the Balkan Albanian Lands seemed in real jeopardy. Frashëri worked to create a unified homeland front for its defence.[9] Frashëri then became the chairman of the Albanian Committee of Janina[9] with the prominent Cham Albanian leader Abedin Dino as its co-founder. There he drafted the project of Declaration of Autonomous Albania within the Ottoman Empire,[9] a project that eventually won over the majority of the representatives from across Albania at the Albanian Congress in Prizren 1878.

His hopes however for an autonomous Albanian state were threatened by Albania's neighbours, including Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria, which were supported by the Russian Empire who strongly opposed an Albanian presence in the Balkans. Frashëri organized then with Ottoman authorities and the Sultan, and with representatives from the Khedivate of Egypt who were of Albanian ancestry, and shared their support. He also met with the representatives of Greece between July and December 1877, primarily for diplomatic grounds in order to form a military coalition to counterpart the Greater Bulgarian and threatening Slavic Expansion.[10] The secret emissary outside of Greece Stephanos Skouloudis rejected the coalition, because he was against an autonomous Albania within its ethnic boundaries, and the talks failed.[10] Frashëri intensified his political alliance with the Ottoman authorities and by 1877, along with many other prominent Albanian compatriots, founded the Central Committee for Defending Albanian Rights based in the Ottoman Capital, in Istanbul [11][4]

Head of Central Committee for Defence and Rights of the Albanian People

At the end of 1877 he founded and was elected chairman of the Central Committee for Defending Albanian Rights (Komiteti i Stambollit), which was formed in Istanbul.[4][12] He gave an important contribution to the elaboration of the political platform that the national movement should adopt after the Russian victory over the Ottoman Empire, and especially after the sign-off of the Treaty of San Stefano.[4] Its goals where to uphold the territorial unity and integrity of Albanian inhabited lands within the empire.[12] According to Frashëri the conditions created by the expansionist trends of Russia and the interests of Western powers to keep the Ottoman Empire alive, and the intentions of Albania's Balkan neighbors to annex Albanian lands, the most appropriate solution would be the creation of an autonomous Albanian state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire, or, at least by creating a unique vilayet under the Ottoman Empire. If this unique Albanian vilayet would be realized, it would sanction Albania's borders, and would give Albanians an upper hand in better preparations for the self-defence of their homeland.

Provisional Government of Albania

The Treaty of San Stefano and later the Berlin Congress triggered profound anxiety among the Albanian population and it spurred their leaders to organize a national defence of the lands they inhabited.[4] Thus in the spring of 1878, influential Albanians met in Constantinople, headed by Frashëri, and other Albanian national movement's leading figures during its early years. They organized a committee to direct the Muslim Albanians' resistance. In May the group called for a general meeting of representatives from all the Albanian-populated lands. On 10 June 1878, about eighty delegates, mostly Muslim religious leaders, clan chiefs, and other influential people from the four Albanian-populated Ottoman vilayets, met in the Kosovo city of Prizren.[4] The delegates set up a standing organization, the League of Prizren, under the direction of a central committee that had the power to impose taxes and raise an army.[4] The League of Prizren worked to gain autonomy for the Albanians and to thwart implementation of the Treaty of San Stefano and that of Berlin Congress, but not to create an independent Albania.[4] The delegates agreed on a minimalist position of preserving Albanian inhabited lands within the empire and upholding local privileges within the Ottoman system.[13] Frashëri and a few others wanted to organise Albanians into national movement and push for a united and autonomous Albania with national and cultural rights.[13] After some discussion other delegates present rejected those proposals.[13]

From the beginning the Ottoman authorities supported the League of Prizren, and had special relations with its head members of the League, especially with Frashëri who held the post of foreign minister of the League, and spokesman to the Sublime Porte. As one of the main authors of the political platform of the Central Committee of Istanbul, which Frashëri publicly stated through articles published in several organs of the Ottoman and European press during the spring of year 1878, he participated actively in establishing the League of Prizren. After the founding of the League, which adopted this platform, Abdyl Frashëri distinguished himself as a leader of the League.[4] Its main activities developed especially in areas of the Janina and Kosovo vilayets. He participated in almost all the major assemblies organized by the General Council of the League of Albanian or its interregional committees. In the League of Prizren's founding assembly he was elected chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee. Frashëri, like other League delegates returned home to create local committees and prepare military forces for resistance[14] and gained support from Albanians in Istanbul and from Southern Albania (Toskëria).[15]

He traveled throughout the Vilayet of Yanina going from Yanina to Preveza and Berat to unite and mobilize Albanians, however some places rejected his attempts.[16] To strengthen his position, Frashëri lobbied the Ottoman government to appoint Mustafa Pasha Vlora as mutasarrif (governor) of Berat.[17] Frashëri, to gain support from southern Muslim Albanians (Tosks) visited tekkes (Sufi monasteries) of the Bektashi order and persuaded their babas (abbots) to assist in the national movement and exercise influence upon notables to join the cause.[14][17] On 1 November 1878 he represented Toskëria in the First Assembly of Debar, where a resolution was adopted to formally require from the Sublime Porte the creation of the autonomous united vilayet of Albania.[18] By 10 November 1878 at the Bektashi tekke in Frashër, an important regional meeting of Tosk Albanians consisting of Orthodox Christians and Muslims gathered by Abdul agreed to his five demands for Albanian sociopolitical rights advocated for in Prizren.[17] He was the principal organizer of the Assembly of Preveza in January 1879, which managed to prevent Çameria being ceded to Greece.[19]

Representing the League of Prizren during May 1879 Frashëri and Mehmet Ali Bey Vrioni sent telegrams to European capitals of Vienna, Paris and Berlin petitioning the Great Powers against Greek and Serb claims to Albanian inhabited land and calling for sociopolitical and education reforms in the empire.[20] A petition was also sent by Frashëri and Vrioni to the Italian prime minister.[21] Frashëri explored his contacts with Italian officials hoping to gain their support on the Albanian question.[22] He understood that Italy wished to keep out other powers from Albania, in particular the southern areas, as it viewed the region strategically important and wanted to increase its influence in the Adriatic Sea.[22] In the spring of 1879 Frashëri headed the Prizren League delegation to visit the capitals of major Powers to protect the integrity of the Albanian lands and the rights of the Albanians.[23] Traveling with Vrioni to Rome in April,[21] the Italian government attempted to persuade Frashëri into cooperating with the Greeks which he rejected saying "the Greeks do not want to recognize our rights; they want subjects and not equals".[24] Ottoman media presented the Rome visit as an attempt by Frasheri and Vrioni to push for Albanian autonomy.[21] Frashëri was also the main promoter to form an interim government. He also led the National Assembly of Gjirokastër that took the decision to create an autonomous Albanian state.[25] He was part of the movement proposing that the Albanians should be armed.[26] Frashëri defended the program of Gjirokastër in the Second Assembly of Debar, where as always led the radical wing of the movement. Although the autonomy program was not accepted by representatives of the moderate power,[25] he moved to Kosovo and there he started to put into action the decisions taken at Gjirokastër.

In 1881 in the founding of the Autonomous interim government that was formed in Prizren in early 1881, headed by Prime minister Ymer Prizreni with Frashëri elected as Minister of its Foreign Affairs. He made important contributions to the political and military preparations that were made for the protection of autonomy against the Ottoman military expedition against the League.[27] A Congresss of Debre was held with 130 delegates that agreed to create an autonomous province and Debar Albanians sent a list of demands to Istanbul for unification of four vilayets into one while stressing Ottoman unity and sovereignty.[28] Of the fourteen signatures a certain Abdullah Hysni, a notable from Toskëria George Gawrych identifies as possibly being Abdul using a pseudonym.[28] Seven weeks later, Frashëri sent a personal telegram to Istanbul on 22 February 1881.[29] Flattering the sultan with honorifics, he stressed that Albania fought to protect the Ottoman state for four years without the vilayets being united into one province and this message was ignored by Abdul Hamid II.[29] Under surveillance from Ottoman authorities in December 1881 Frashëri left Istanbul for Prizren to exercise influence over the League government however while on a stopover in Debar an assassination attempt occurred by local Ottoman supporters.[30] Frashëri exploited the situation by rallying Debar inhabitants to his side against the Ottomans resulting in the expulsion of the Ottoman administrator (Mutasarrıf) and supporters.[30]

Suppression of the League of Prizren, arrest and imprisonment

After the Provisional Government of the League was eventually suppressed by the Ottoman Empire, and numerous battles were held between the League Army and Ottoman Forces, fought in summer of 1881, Frashëri along with many other members and notables of the Prizren League, was captured and arrested by the commander in chief Marshall Dervish Pasha[31] and was temporarily sentenced to death[32] by an Ottoman Special Trial. The sentence however was reduced by Abdul Hamid II to prison with hard labour and he was incarcerated in a castle jail in Prizren[31][32] for 3 years. After 3 years in prison (1882–1885) and an extradition to Istanbul, he was finally released for health reasons in 1886, with the conditional to give up any political or patriotic activity.

During this time Frashëri corresponded with European leaders like Italian prime minister Francesco Crispi on the Albanian geopolitical question.[33] Frashëri's views overall were that partition of Albania by foreign powers would result in fierce Albanian resistance.[33] The solution according to him was European intervention resulting in an autonomous or small kingdom of Albania defined along ethnographic and geographic frontiers within a Balkan confederation or under a great power that adhered to European laws and political organisation.[33] Although ill and isolated, he never gave up his patriotic ideas until his death on 23 October 1892 in Istanbul.[31] The Turkish government allowed for his remains to be transferred to Albania[1] and in 1978 were brought to Tirana on the 100th anniversary of the League of Prizren.

External links

- Frashëri family tree (Last update: 2015-05-19)

References

- Gawrych 2006, p. 200.

- Kopeček, Michal; Ersoy, Ahmed; Gorni, Maciej; Kechriotis, Vangelis; Manchev, Boyan; Trencsenyi, Balazs; Turda, Marius (2006), Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945), 1, Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press, p. 348, ISBN 963-7326-52-9,

the first political ideologue of the Albanian Revival...

- Gawrych 2006, p. 204.

- Skendi 1967, pp. 36–38.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 13.

- Robert Elsie (2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. I.B.Tauris. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4.

- Gawrych 2006, pp. 40–42.

- Skendi 1967, p. 119.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 40.

- Skendi 1967, p. 55.

- http://www.shqiperia.com/kat/m/shfaqart/aid/294/Komiteti-i-Stambollit-dhe-platforma-e-tij-politike.html

- Gawrych 2006, p. 44.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 46.

- Skendi 1967, pp. 41–43.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 50.

- Gawrych 2006, pp. 52, 60, 71.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 52.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 51.

- Skendi 1967, pp. 70–73.

- Gawrych 2006, pp. 56–57, 60.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 57.

- Gawrych 2006, pp. 52–53.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 60.

- Skendi 1967, pp. 85–86.

- Skendi 1967, pp. 88–92.

- Skendi 1967, pp. 79–80.

- Skendi 1967, pp. 101–102.

- Gawrych 2006, pp. 66–67.

- Gawrych 2006, p. 67.

- Skendi 1967, p. 98.

- Skendi 1967, p. 105.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9781845112875.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 165–166, 169. ISBN 9781400847761.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)