2014 Pacific hurricane season

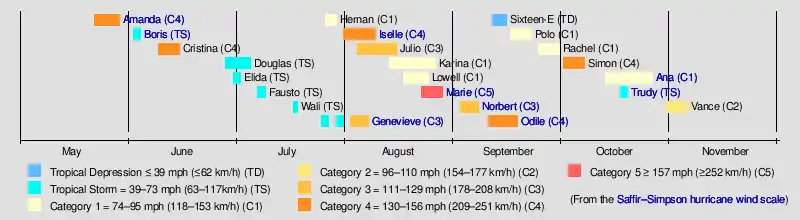

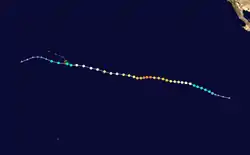

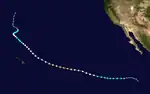

The 2014 Pacific hurricane season was the fifth-busiest season since reliable records began in 1949, alongside the 2016 season. The season officially started on May 15 in the East Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Pacific basin.

| 2014 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 22, 2014 |

| Last system dissipated | November 5, 2014 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Marie |

| • Maximum winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 918 mbar (hPa; 27.11 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 23 |

| Total storms | 22 |

| Hurricanes | 16 (record high, tied with 1990, 1992 and 2015) |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 9 |

| Total fatalities | 49 total |

| Total damage | ≥ $1.52 billion (2014 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Entering the season, expectations of tropical activity were high, with most weather agencies predicting a near or above average season. The season began with an active start, with three tropical cyclones developing before June 15, including two Category 4 hurricanes, of which one became the strongest tropical cyclone ever recorded in May in the East Pacific. After a less active period in late June and early July, activity once again picked up in late July. Activity increased in August, which featured four major hurricanes, and persisted throughout September and October. However, activity finally waned by early November. Overall, the 22 tropical storms marked the highest total in 22 years. In addition, a record-tying 16 hurricanes developed. Furthermore, there were total of nine major hurricanes, Category 3 or greater on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, including a then-record-tying eight in Eastern Pacific proper (east of 140°W).

The active season resulted in numerous records and highlights. First, Hurricane Amanda was the strongest May hurricane and earliest Category 4 on record. A month later, Hurricane Cristina became the earliest second major hurricane, although it was surpassed by Hurricane Blanca the following year. In August, Hurricane Iselle became the strongest tropical cyclone on record to strike the Big Island of Hawaii while Hurricane Marie was the first Category 5 hurricane since 2010. The following month, Hurricane Odile became the most destructive tropical cyclone of the season and the most intense and destructive tropical cyclone to make landfall over the Baja California peninsula.

Seasonal forecasts

| Record | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (1981–2010): | 15.4 | 7.6 | 3.2 | [1] | |

| Record high activity: | 1992: 27 | 2015: 16 | 2015: 11 | [2] | |

| Record low activity: | 2010: 8 | 2010: 3 | 2003: 0 | [2] | |

| Date | Source | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| March 12, 2014 | SMN | 15 | 7 | 3 | [3] |

| April 10, 2014 | SMN | 14 | 7 | 5 | [4] |

| May 22, 2014 | CPC | 14–20 | 7–11 | 3–6 | [5] |

| July 31, 2014 | SMN | 17 | 8 | 5 | [6] |

| Area | Named storms | Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | Ref | |

| Actual activity: | EPAC | 20 | 15 | 9 | |

| Actual activity: | CPAC | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Actual activity: | 22 | 16 | 9 | ||

On March 12, 2014, the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN) issued its first outlook for the Pacific hurricane season, expecting a total of fifteen named storms, seven hurricanes, and three major hurricanes[nb 1].[3] A month later, the agency revised their outlook to fourteen named storms, seven hurricanes, and five major hurricanes, citing the anticipated development of El Niño for above-average activity, compared to the 1949–2013 average of 13.2,[4] On May 22, the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) announced its prediction of 14 to 20 named storms, seven to eleven hurricanes, three to six major hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) within 95–160% of the median.[5] It also called for a 50% chance of an above-normal season, a 40% chance of a near-normal season, and a 10% chance of a below-normal season. Similar to the SMN outlook, the basis for the forecast was the expectation of below average wind shear and above average sea surface temperatures, both factors associated with El Niño conditions. The CPC also noted that the Eastern Pacific was in a lull that first began in 1995; however, they expected that this would be offset by the aforementioned favorable conditions.[7] Within the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC)'s jurisdiction, four to seven tropical cyclones were expected to form, slightly above the average of four to five tropical cyclones.[8] On July 31, the SMN released their final forecast, raising the numbers to 17 named storms, 8 hurricanes and 5 major hurricanes.[6]

Seasonal summary

The well-above average activity in 2014 was reflected by an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index of 160.3 units for the East Pacific and 38.49 units for the Central Pacific, giving a total of 198.79 units.[nb 2] The total ACE for the East Pacific was 43% above the 1981–2010 average and ranked as the seventh-highest since 1971.[9]

The season's first named storm, Amanda, developed on May 23, shortly after the official start to the Pacific hurricane season on May 15. On May 24, the system intensified into a hurricane, transcending the climatological average date of June 26 for the first hurricane. The next day, Amanda attained major hurricane status, over a month sooner than the average date of July 19.[10] Owing to Amanda's extreme intensity the ACE value for May was the highest on record in the East Pacific at 18.6 units, eclipsing the previous record of 17.9 units set in 2001.[11][nb 2] Hurricane Cristina became the second's major hurricane, the system broke the previous record set by Hurricane Darby in 2010 which reached major status on June 25. However, this record was broken by Hurricane Blanca in 2015 which reached major status on June 3. Through June 14, the seasonal ACE reached its highest level since 1971, when reliable records began, for so early in the season. By the end of June, the ACE total remained at 230% of the normal value,[12] before subsiding to near-average levels to end July.[13] By late July, the basin became re-rejuvenated, with 3 systems forming during the final 10 days of the month. Activity in August ramped up significantly, with four hurricanes developing during the month, two of which became major hurricanes, excluding Iselle and Genevieve, which formed in July, but became a major hurricane during August. By the end of August, ACE values rose to 60% above the 30-year average.[14]

Continued, though less prolific, activity extended through September with four hurricanes developing that month. ACE values remained 45% above-average by the end of the month.[15] Following the rapid intensification of Hurricane Simon to a Category 3 hurricane during the afternoon of October 4, the 2014 season featured the highest number of major hurricanes in the Eastern Pacific basin since the advent of satellite imagery. With eight such storms east of 140°W, the year tied with the record set in the 1992 season.[16][17] However, this record was surpassed by the 2015 Pacific hurricane season.

Systems

Hurricane Amanda

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 22 – May 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min) 932 mbar (hPa) |

Amanda originated as a tropical wave that moved into the eastern Pacific on May 16. It continued west, organizing into a tropical depression around 18:00 UTC on May 22 and further intensifying into a tropical storm a day later. After attaining hurricane strength at 12:00 UTC on May 24, the storm began a period of rapid intensification, peaking as high-end Category 4 hurricane with winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) within 24 hours; this made Amanda the strongest May tropical cyclone and second earliest major hurricane on record in the basin.[18] As the system slowed to a crawl, cold water upwelling beneath it began a weakening trend. The hurricane fell to tropical storm strength early on May 28, weakened to tropical depression strength early on May 29, and dissipated around 18:00 UTC that day.[19]

A river near Coyuca de Benítez overflowed its banks. Three trees were brought down and a vehicle in Acapulco was destroyed,[20] near where one person was killed.[21] In Colima, minor landslides occurred, resulting in the closure of Federal Highway 200.[22] Two people perished in Michoacán[23] while several roads were destroyed in Zitácuaro.[24]

Tropical Storm Boris

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 2 – June 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) |

The formation of Boris is attributed to a low-level trough that entered the East Pacific from the southwestern Caribbean Sea on May 28. A broad area of low pressure developed in association with the trough south of the Mexico–Guatemala border two days later, and the disturbance steadily organized with aid from an eastward-moving convectively-coupled kelvin wave. By 18:00 UTC on June 2, the system acquired enough organization to be deemed a tropical depression. Tracking northward, the depression steadily became better defined as spiral bands developed over the eastern semicircle of the circulation. After intensifying into a tropical storm at 12:00 UTC on June 3 and attaining peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) six hours later, increasing land interaction caused Boris to begin weakening. It was downgraded to a tropical storm early on June 4 and subsequently degenerated into a remnant low at 18:00 UTC. The remnant low turned northwestward and dissipated shortly thereafter.[25]

Posing a considerable rainfall and mudslide threat to Guatemala, classes were suspended in nine school districts, impacting 1.25 million pupils.[26] Similarly, some classes were suspended in the Mexican states of Chiapas and Oaxaca.[27][28] In the former, roughly 16,000 people were evacuated out of hazardous areas.[29] Most of the impacts associated with Boris were due to its developing precursor, whose heavy rainfalls caused 20 mudslides, killing five and resulting in extensive property damage.[26][30] Heavy rainfall in Chiapas caused rivers to overflow their banks,[31] resulting in minor damage.[32] Overall, the effects of Tropical Storm Boris and its precursor killed six people across Central America.[26][33]

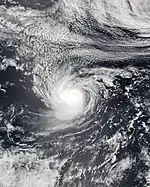

Hurricane Cristina

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 9 – June 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min) 935 mbar (hPa) |

The complex interaction of a tropical wave, disturbance within the Intertropical Convergence Zone, and convectively-coupled kelvin wave led to the formation of a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC on June 9. Northerly shear limited intensification of the cyclone initially, but it became Tropical Storm Cristina eighteen hours after formation. A relaxation in upper-level winds allowed the system to begin a period of rapid intensification on June 11, and Cristina became both the earliest second hurricane and major hurricane on record at the time before attaining its peak as a Category 4 with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) around 12:00 UTC on June 12. The combination of an eyewall replacement cycle, cooler waters, and entrainment of dry air caused Cristina to begin weakening shortly after peak; it fell to tropical storm intensity early on June 14 and degenerated to a remnant low by 06:00 UTC the next morning. The low moved erratically within low-level flow and dissipated early on June 19.[34]

Under the anticipation of 12 ft (3.7 m) waves,[35] a "yellow" alert was issued for Colima, Guerrero, Oaxaca, and parts of Jalisco and Michoacan.[36] Along Manzanillo, strong waves resulted in minor flooding that damaged one road.[37]

Tropical Storm Douglas

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 28 – July 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 999 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on June 17, tracking across the Atlantic Ocean with inappreciable organization throughout the following days. The wave crossed Central America on June 25, where deep convective activity increased. On June 28, the disturbance became distinctively better defined with a well-defined center and spiral banding, signifying the formation of a tropical depression by 18:00 UTC while positioned about 345 mi (555 km) south-southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico. Steered west-northwest and eventually northwest under the influence of a mid-level ridge, the broad cyclone slowly intensified into a tropical storm by 00:00 UTC on June 30, attaining peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) late the next day. Thereafter, a track over cooler waters and into a drier environment caused the system to begin weakening; at 06:00 UTC on July 5, Douglas degenerated into a non-convective remnant low well west of Baja California. The remnant low turned slowly west-northwest prior to dissipating on July 8.[38]

Tropical Storm Elida

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 30 – July 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A well-defined tropical wave moved emerged off the western coast Africa on June 20. After entering the East Pacific a week later, shower and thunderstorm activity began to increase. Although the system lacked a closed low initially, a small circulation was noted by 06:00 UTC on June 30, and the system was declared Tropical Storm Elida accordingly. Paralleling the southwestern coast of Mexico, the cyclone attained peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) before strong northwesterly wind shear from nearby Tropical Storm Douglas caused the storm to become disheveled. It weakened to a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on July 2 and degenerated into a remnant low six hours later. The remnant low drifted southeastward before dissipating early on July 3.[39]

Tropical Storm Fausto

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 7 – July 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa on June 22 and entered the East Pacific eight days later. On July 4, convection increased with the aid of a convectively-coupled kelvin wave, and two days later, a broad area of low pressure formed along the wave axis well south-southwest of Baja California. After further organization, the disturbance was declared a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on July 7. Steered westward around a subtropical ridge, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Fausto six hours later and simultaneously attained peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). By early on July 9, Fausto weakened to a tropical depression as dry air became entrained into the circulation. The low-level center opened up into a trough by 12:00 UTC, marking the demise of the cyclone.[40]

Tropical Storm Wali

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 17 – July 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began monitoring a large area of disturbed weather in association with a tropical wave well southwest of the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula on July 13.[41] After crossing into the central Pacific, the disturbance gradually organized, and it acquired enough organization to be declared a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on July 17.[42] An hour later, data from an ASCAT pass revealed winds up to 45 mph (75 km/h), and the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Wali.[43] Steered west-northwestward around a mid-level ridge to the cyclone's northeast, increasing wind shear caused the cloud pattern associated with Wali to become disorganized; at 18:00 UTC on July 18, the system was downgraded to a tropical depression, and by 00:00 UTC the following afternoon, Wali was declared a remnant low after having been devoid of deep convection.[42]

Hurricane Genevieve

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 25 – August 7 (Exited basin) |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 965 mbar (hPa) |

A disturbance first identified south of Panama on July 15 continued west and organized into a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on July 25; it intensified into Tropical Storm Genevieve six hours later. Increasing wind shear caused the cyclone to degenerate to a remnant low early on July 28 after it entered the central Pacific, and although it regenerated and subsequently intensified into a tropical storm again two days later, an unfavorable environment caused it to lose its status as a tropical cyclone for a second time around 00:00 UTC on August 1. Genevieve once again regenerated to a tropical depression around 06:00 UTC on August 2, and it continued west across the central Pacific as a low-end system for several days. An intensification trend began in earnest on August 5, and Genevieve attained hurricane strength around 12:00 UTC the next morning before beginning a period of rapid intensification. It attained major hurricane intensity before crossing the International Date Line into the western Pacific early on August 7, where the system further intensified into a Category 5-equivalent typhoon.[44]

Hurricane Hernan

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 26 – July 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 992 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa on July 12 and reached the East Pacific by July 21. Initially devoid of convection, shower and thunderstorm activity increased significantly a few days later, possibly due to the passage of a convectively-coupled kelvin wave. Following the development of a closed area of low pressure, the disturbance was designated as a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on July 26 while located about 405 mi (650 km) southwest of Zihuatanejo, Mexico; twelve hours later, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Hernan. Influenced by a mid-level ridge over the southern United States and Mexico, the cyclone moved west-northwest to northwest while quickly strengthening. At 18:00 UTC on July 27, Hernan intensified into a Category 1 hurricane and simultaneously attained peak winds of 75 mph (120 km/h). Thereafter, increasing westerly shear and cooling ocean temperatures caused the storm to begin weakening. Hernan was downgraded to a tropical storm at 06:00 UTC on July 28 and degenerated into a remnant low at 12:00 UTC the following day. The remnant low slowed and turned west prior to dissipating early on July 31.[45]

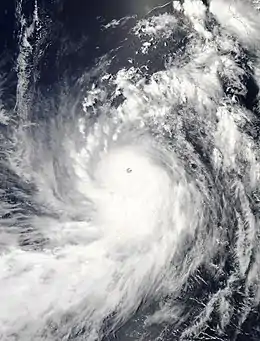

Hurricane Iselle

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 31 – August 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) 947 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged from Africa on July 14, eventually organizing into a tropical depression over the eastern Pacific around 12:00 UTC on July 31; six hours later, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Iselle. A mid-level ridge over Mexico directed the system west-northwest, while improving upper-level winds allowed Iselle to begin rapid intensification. Iselle reached hurricane intensity around 00:00 UTC on August 2 and major hurricane strength by 12:00 UTC the next day. As the hurricane moved parallel to the 26 °C isotherm, its cloud pattern evolved to resemble an annular hurricane, with a large eye and lack of convective bands. It intensified into a Category 4 hurricane early on August 4 and attained peak winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) around 18:00 UTC that day. Increased wind shear prompted a weakening trend as the system entered the central Pacific, and it weakened to a tropical storm by 06:00 UTC on August 8 before making landfall just east of Pahala, Hawaii, with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) six hours later. The high terrain of Hawaii contributed to the disruption of Iselle's cloud pattern, and it degenerated to a remnant low by 06:00 UTC on August 9 before dissipating west of the island late the next day.[46]

Hurricane Julio

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 4 – August 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) 960 mbar (hPa) |

Julio originated from a tropical wave that moved off Africa on July 20, ultimately organizing into a tropical depression well southwest of Baja California by 00:00 UTC on August 4. After intensifying into a tropical storm six hours later, it tracked west-northwest. Light northeasterly wind shear allowed the cyclone to reach hurricane strength around 06:00 UTC on August 6 and further organize to its peak as a Category 3 with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) two days later, despite cool ocean temperatures. Shortly after entering the central Pacific, Julio began to weaken as a result of cold water upwelling. Although the cyclone fell to a tropical storm early on August 12, an upper-level environment still favorable for strengthening allowed Julio to briefly regain hurricane strength the next day. Julio fell below hurricane strength once again early on August 14 as southwesterly wind shear increased, weakened to a tropical depression early on August 15, and degenerated to a remnant low around 18:00 UTC that day. The low dissipated over the far northern Pacific on August 18.[47]

Hurricane Karina

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 13 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 983 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave left Africa on July 28, crossing Central America to become a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC on August 12. The newly-formed system strengthened as it moved west-northwest, becoming Tropical Storm Karina around 12:00 UTC the next morning, and further intensifying to a hurricane by 18:00 UTC on August 14. Increasingly easterly shear eroded the hurricane's inner core, and Karina dramatically weakened as a result. By August 19, as it remained disorganized, a large ridge to its north diminished and a sprawling tropical cyclone—Lowell—formed to its east, leading to weak steering currents that allowed Karina to meander. It executed a three-day-long cyclonic loop, while environmental conditions began to improve, and became a hurricane again by 18:00 UTC on August 22; twelve hours later, Karina reached peak winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). Lower ocean temperatures and increasing shear soon deteriorated the storm's cloud pattern, and it fell below hurricane strength early on August 24. Lacking persistent convection, Karina degenerated to a remnant area of low pressure by 18:00 UTC on August 26, cementing its status as the seventh longest-lived tropical cyclone on record in the East Pacific. The remnant low moved around the southern portion of nearby Hurricane Marie and dissipated early on August 28.[48]

Hurricane Lowell

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 17 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave departed Africa on August 1, crossing Central America to become a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC on August 17. With a circulation about 920 mi (1,480 km) across, the unusually large system only slowly organized, becoming Tropical Storm Lowell around 18:00 UTC on August 18. Strong upper-level winds that had been plaguing the system weakened as it moved west then northwest, and its large circulation contracted, allowing Lowell to attain hurricane strength with peak winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) by 12:00 UTC on August 21 as a large eye became evident. Low wind shear allowed Lowell to only slowly decrease in intensity over the coming days despite cooling ocean temperatures. It became a tropical depression early on August 24 and degenerated to a remnant low around 12:00 UTC that morning. The post-tropical cyclone turned west and remained distinct until late on August 28, when it dissipated into an open trough well northeast of Hawaii.[49]

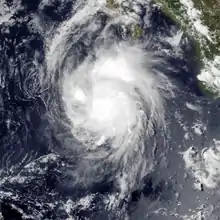

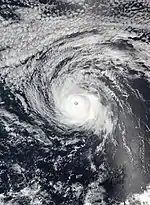

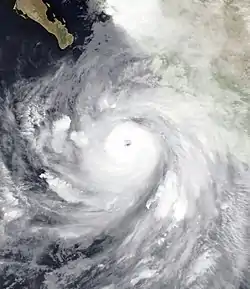

Hurricane Marie

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 22 – August 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min) 918 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave crossed the coast of Africa on August 10, developing into a tropical depression over the East Pacific around 00:00 UTC on August 22. Embedded in a very favorable environment, the system intensified into Tropical Storm Marie six hours later, part of a larger 66-hour period of rapid intensification that ultimately brought the storm to its peak as a Category 5 hurricane with winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) around 18:00 UTC on August 24. An eyewall replacement cycle later that day curbed the strengthening trend, and by August 26, a persistent ridge over the southern United States directed Marie into cooler ocean waters; both of these events caused steady to rapid weakening. Marie weakened to a tropical storm around 18:00 UTC on August 27 and degenerated to a remnant low a day later. The low turned west and eventually dissipated, early on September 2.[50]

Hurricane Norbert

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 2 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 950 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave departed Africa on August 18 and reached the East Pacific nearly two weeks later, where it steadily organized into Tropical Storm Norbert around 12:00 UTC on September 2. Departure from the ITCZ resulted in the system moving north initially, but a series of ridges over Mexico directed it on a west to northwest track for the remainder of its duration. Over anomalously warm ocean waters, and part of an increasingly favorable shear regime, Norbert intensified into a hurricane by 00:00 UTC on September 4. After levelling off in intensity the next day, the system quickly strengthened to its peak as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) around 06:00 UTC on September 6. Norbert passed west of Baja California and entered a drier environment, causing a rapid decay that caused it to degenerate to a remnant low by 00:00 UTC on September 7. The low meandered offshore before dissipating early on September 11.[51]

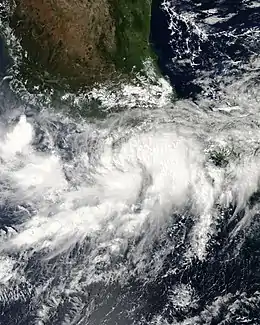

Hurricane Odile

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 10 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) 918 mbar (hPa) |

The most destructive hurricane of the 2014 season began as a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on September 10 from a tropical wave that first left Africa on August 28. Situated between two mid-level ridges, the system moved northwest while steady intensifying, becoming Tropical Storm Odile six hours after formation and further strengthening into a hurricane by 06:00 UTC on September 13. A period of rapid intensification began at that time, with Odile's winds increasing from 75 mph (120 km/h) to a peak of 140 mph (220 km/h) within a 24-hour timeframe. The onset of an eyewall replacement cycle caused the hurricane to weaken slightly on September 14, but Odile still maintained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) when it made landfall near Cabo San Lucas at 04:45 UTC. It continued up the spine of Baja California before curving northeast into the Gulf of California, ultimately making a second landfall near Alvaro Obregón, Mexico as a minimal tropical storm on September 17. Odile progressed inland and quickly dissipated over the mountainous terrain of Mexico by 06:00 UTC the next day.[52]

Tropical Depression Sixteen-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 11 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave that cannot be traced back to Africa was first noted over the central Atlantic on August 29. It entered the East Pacific four days later, where an increase in organization led to the development of a tropical depression well southwest of Baja California around 06:00 UTC on September 11. A mid-level ridge to its east directed the newly-formed system northwest to north initially, but as this ridge gradually dissipated, nearby Hurricane Odile became the dominant steering mechanism and forced the depression generally east. In close proximity to Odile, the depression was heavily sheared and thus failed to intensify into a tropical storm. It instead degenerated to a remnant low around 06:00 UTC on September 15 before weakening to an open trough the next morning.[53]

Hurricane Polo

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 16 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 979 mbar (hPa) |

The interaction of a westward-tracking tropical wave that emerged off the coast of Africa on September 4, an eastward-tracking kelvin wave, and an elongated surface trough led to the formation of Tropical Storm Polo by 00:00 UTC on September 16 about 310 mi (500 km) south of Puerto Escondido, Mexico. Tracking northwest within an environment conducive for strengthening, Polo intensified into a Category 1 hurricane and reached peak winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) by 00:00 UTC on September 18 as an eye became evident on satellite imagery. A sharp increase in wind shear quickly thereafter caused the storm's center to become exposed, and a reconnaissance mission indicated that Polo weakened to a tropical storm by 18:00 UTC that day. After maintaining intensity for about a day, the cyclone weakened to a tropical depression by 06:00 UTC on September 22 and further decreased into a remnant low six hours later. The low turned southwestward before dissipating well southwest of the southern tip of Baja California on September 26.[54]

One tourist perished and three others, including two fisherman, went missing in Guerrero. A total of 190 restaurants and 20 shops were damaged.[55] Damage in the state totalled at about 100 million pesos (US$7.6 million).[56]

Hurricane Rachel

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous tropical wave moved off Africa on September 7, aiding in the formation of Hurricane Edouard before entering the East Pacific on September 19. There, it interacted with pre-existing southwesterly flow, eventually leading to the formation of a tropical depression around 18:00 UTC on September 23. Moderate northeast wind shear prevented the west-northwest-moving depression from becoming Tropical Storm Rachel until 00:00 UTC on September 25. The next day, Rachel's original center dissipated and a new one formed under deep convection. Environmental conditions became more favorable on September 17, when the cyclone reached hurricane strength at 18:00 UTC. It attained peak winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) six hours later before dry air, wind shear, and cooler waters caused a quick decay as the storm moved north. Rachel fell below hurricane strength around 06:00 UTC on September 29 and degenerated to a remnant low by 12:00 UTC the next morning. It dissipated early on October 3.[57]

Hurricane Simon

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 1 – October 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min) 946 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave departed Africa on September 14 and continued into the eastern Pacific ten days later, where it interacted with the ITCZ and produced a large area of convection. An area of low pressure developed within this convection and organized while moving west-northwest, becoming a tropical depression by 18:00 UTC on October 1 and intensifying into Tropical Storm Simon twelve hours later. Simon only slowly strengthened initially, limited by its broad size. However, beginning around 18:00 UTC on October 3, it began a 30-hour period of rapid intensification wherein maximum winds increased from 65 mph (100 km/h) to 130 mph (215 km/h), a Category 4 hurricane. The system turned northwest around the periphery of a ridge, tracking into a region of low ocean heat content that prompted cold water upwelling. Simon rapidly weakened to a tropical storm early on October 6 before gradually degenerating to a remnant area of low pressure around 00:00 UTC on October 8. The post-tropical cyclone turned east and moved ashore Baja California Sur several hours later before dissipating over rugged terrain by 06:00 UTC the next day.[58]

Hurricane Ana

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 13 – October 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 985 mbar (hPa) |

An area of deep convection and a low pressure area merged and became Tropical Depression Two-C on October 13. It slowly intensified and turned northwestward, developing into Tropical Storm Ana. The storm continued intensifying and was upgraded to a strong tropical storm. Ana turned westward, strengthening into a Category 1 hurricane on October 17. As Ana kept south of the island chain, the hurricane produced large waves and winds. Consequently, the Central Pacific Hurricane Center initiated tropical storm watches. Ana was downgraded to a tropical storm very early on October 20.[59]

Beginning on October 15, various tropical cyclone warnings and watches were issued for Hawaii, starting with a tropical storm watch for the Big Island.[60] Three days later, a tropical storm warning was issued for Kauai and Nihau,[61] and was extended to include portions of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.[62] The threat of the storm forced parks and beaches to close in the state.[63] While passing south of Hawaii, Ana produced heavy rainfall on most of the islands, peaking at 11.67 in (296 mm) at Keaumo on the Big Island.[64] The rains caused the Sand Island water treatment plant in Honolulu to overflow, which sent about 5,000 gallons of partially treated wastewater into Honolulu Harbor.[65] On October 25, Ana was downgraded to a tropical storm for the second time. Ana continued on a track to the northwest and weakened even further. The system eventually turned north and once again re-strengthened into a high-end tropical storm. Ana turned northwest and soon northeast, fluctuating in strength before being picked up by the jet stream. While racing off to the northeast at nearly 35 knots, Ana once again strengthened into a Category 1. After yet again being downgraded to a tropical storm, Ana became extratropical far to the northeast of Hawaii on October 26.[59]

Tropical Storm Trudy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 17 – October 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) |

A broad area of low pressure became established across the East Pacific during the first week of October. In conjunction with an eastward-moving convectively-coupled kelvin wave and a Tehuantepecer, a significant increase in convection in association with the low was observed. Following several days of consolidation, the disturbance acquired sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on October 17; six hours later, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Trudy. Amid an exceptionally favorable environment, Trudy quickly intensified as it moved north-northwestward, with the formation of an inner core and eye evident on conventional and microwave satellite imagery. At 09:15 UTC on October 18, the cyclone reached peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) as it moved ashore just southeast of Marquelia, Mexico. Trudy quickly weakened following landfall, weakening to a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC and dissipating by 06:00 UTC on October 19, while located over the mountains of southern Mexico. Trudy's remnant energy continued across Mexico and contributed to the development of Tropical Storm Hanna/Tropical Depression Nine on October 21, 2014.[66]

In preparation for the cyclone, various tropical cyclone watches and warnings were issued for the coastline of southeastern Mexico.[66] A "yellow" alert was initially activated for Guerrero;[67] however, following Trudy's period of rapid intensification, this was abruptly upgraded to a "red" alert for southeastern portions of the state as well as southwestern Oaxaca, and the remainder of the two states were placed under an "orange" alert.[68] Upon making landfall, torrential rainfall associated with the cyclone caused numerous landslides and flooding. Approximately 4,075 people were evacuated from the most-at-risk locations. A total of 5,000 homes were affected by the storm, 218 of which damaged and an additional six completely destroyed.[69] At the height of the storm, more than 20,000 households were without electricity.[70] A state of emergency was declared for 35 municipalities across Guerrero and 100 municipalities in Oaxaca.[71][72] Overall, Trudy was responsible for nine deaths: eight in Guerrero and one in Campeche.[73][74]

Hurricane Vance

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 30 – November 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 964 mbar (hPa) |

A trough that extended from the Atlantic's Tropical Storm Hanna into the eastern Pacific led to widespread convection south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec in late October. This disturbance remained disorganized until 06:00 UTC on October 30, when a well-defined center and organized thunderstorm activity led to the formation of a tropical depression. The cyclone intensified into Tropical Storm Vance twelve hours later but ultimately weakened some due to the entrainment of dry air. After drifting for a day, mid-level ridging over the far eastern Pacific caused the storm to move west-northwest. Improving environmental conditions allowed it to become a hurricane around 12:00 UTC on November 2 and rapidly strengthen to a Category 2 with winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) the next day. Vance curved northeast into a higher shear environment by November 4, causing the system to weaken from a Category 2 hurricane to a tropical depression in an 18-hour period. The depression opened up into a trough around 12:00 UTC on November 5 and moved ashore Sinaloa and Nayarit several hours later before dissipating.[75]

Heavy rains from the remnants of Vance, lasting 40 hours in some places,[76] damaged 2,490 homes across 7 municipalities in the Mexican state of Durango.[77] Flooding up to 1 m (3.3 ft) in depth affected ten homes in San Dimas. Thirty families in the area were evacuated due to the rising water. A few landslides were reported in the region, though no major damage resulted.[76]

Storm names

The following names were used to name storms that formed in the northeastern Pacific Ocean during 2014. Retired names, were announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2015. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2020 season.[78] This is the same list used in the 2008 season with the exception of Amanda, which replaced Alma; the name Amanda was used for the first time this year.

|

For storms that form in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility, encompassing the area between 140°W and the International Date Line, all names are used in a series of four rotating lists.[79] The next four names slated for use are shown below. Two names, Wali and Ana, were used.

|

|

|

Retirement

On April 17, 2015, at the 37th session of the RA IV hurricane committee, the name Odile was retired due to the damage and deaths it caused and will not be used for another Pacific hurricane. Odile was replaced with Odalys for the 2020 season.[80]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that have formed in the 2014 Pacific hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parenthesis, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2014 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amanda | May 22 – 29 | Category 4 hurricane | 155 (250) | 932 | Southwestern Mexico, Western Mexico | Minimal | 3 | |||

| Boris | June 2 – 4 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 998 | Southwestern Mexico, Guatemala | $54.1 million | 6 | |||

| Cristina | June 9 – 15 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 (240) | 935 | Southwestern Mexico, Western Mexico | Minimal | None | |||

| Douglas | June 28 – July 5 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 999 | None | None | None | |||

| Elida | June 30 – July 2 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1002 | Western Mexico | None | None | |||

| Fausto | July 7 – 9 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Wali | July 17 – 19 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Genevieve | July 25 – August 7[nb 3] | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 965 | None | None | None | |||

| Hernan | July 26 – 29 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 992 | None | None | None | |||

| Iselle | July 31 – August 9 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 947 | Hawaii | >$148 million | 1 | |||

| Julio | August 4 – 15 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 960 | Hawaii | None | None | |||

| Karina | August 13 – 26 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 983 | None | None | None | |||

| Lowell | August 17 – 24 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 980 | None | None | None | |||

| Marie | August 22 – 28 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 918 | Southwestern Mexico, Southern California | $20 million | 6[81] | |||

| Norbert | September 2 – 7 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 950 | Western Mexico, Baja California Peninsula, Southwestern United States | $28.3 million | 5 | |||

| Odile | September 10 – 18 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 918 | Western Mexico, Baja California Peninsula, Northwestern Mexico, Southwestern United States, Texas | $1.25 billion | 18 | |||

| Sixteen-E | September 11 – 15 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1005 | Baja California Sur | None | None | |||

| Polo | September 16 – 22 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 979 | Western Mexico, Baja California Peninsula | $7.6 million | 1 | |||

| Rachel | September 24 – 30 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 980 | None | None | None | |||

| Simon | October 1 – 7 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 946 | Western Mexico, Baja California Peninsula, Southwestern United States | Unknown | None | |||

| Ana | October 13 – 26 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 985 | Hawaii, Western Canada, Alaskan Panhandle | Minimal | None | |||

| Trudy | October 17 – 19 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 998 | Southwestern Mexico | >$12.3 million | 9 | |||

| Vance | October 30 – November 5 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 964 | Western Mexico, Northwestern Mexico | Minimal | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 23 systems | May 22 – November 5 | 160 (260) | 918 | ≥$1.52 billion | 49 | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2014

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- Pacific hurricane season

- 2014 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2014 Pacific typhoon season

- 2014 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2013–14, 2014–15

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2013–14, 2014–15

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2013–14, 2014–15

Footnotes

- A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.

- The totals represent the sum of the squares for every tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2014 Pacific hurricane season/ACE calcs.

- Genevieve did not dissipate on August 7. It crossed the International Date Line, beyond which point it was then referred to as Typhoon Genevieve.

References

- "Background Information: East Pacific Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved 1 October 2020. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Previsiones Meteorológicas Generales 2014 Ciclones Tropicales (PDF). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. March 12, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 23, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- "Proyección de la Temporada de Tormentas Tropicales y Huracanes 2014 (PDF). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. April 10, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- "NOAA predicts near-normal or above-normal Eastern Pacific hurricane season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- http://smn.cna.gob.mx/tools/DATA/Ciclones%20Tropicales/Proyecci%C3%B3n/2014.pdf

- "NOAA: 2014 Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season Outlook". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 22, 2014.

- "NOAA expects near-normal or above-normal Central Pacific hurricane season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- Hurricane Specialists Unit (December 1, 2014). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (.TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". National Hurricane Center. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- Hurricane Specialists Unit (June 1, 2014). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (.TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Hurricane Specialist Unit (July 1, 2014). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- Hurricane Specialist Unit (August 1, 2014). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (.TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- Hurricane Specialist Unit (September 1, 2014). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (.TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- Hurricane Specialists Unit (October 1, 2014). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (.TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- Daniel P. Brown (September 14, 2014). Hurricane Odile Discussion Number 17. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- Jack L. Beven II (October 4, 2014). Hurricane Simon Discussion Number 13. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- Michael J. Brennan (May 24, 2014). Hurricane Amanda Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- Stacy R. Stewart (June 24, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Amanda (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- "Amanda alcanza categoría 4; mantienen alerta" [Amanda reached category 4; remain alert]. El Universal (in Spanish). May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- "Causa Amanda un muerto en Guerrero" [Cause Amanda dead in Guerrero]. El Universal (in Spanish). May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- "Huracán Amanda causa derrumbes en Colima" [Hurricane Amanda cause landslides in Colima]. El Universal (in Spanish). May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- "Lluvias de Amanda dejan dos muertos en Michoacán" [Amanda Rains leave two dead in Michoacan]. El Universal (in Spanish). May 28, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- "Heavy rains caused by storm Amanda left three dead in Mexico" [Amanda Rains leave two dead in Michoacan]. Terra Noticas (in Spanish). May 28, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- Daniel P. Brown (August 12, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Boris (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- "Autoridades suspenden clases en 9 departamentos de Guatemala por lluvias" [Classes suspended by authorities in 9 of Guatemala's provinces due to rain]. Agency Guatemala de Noticas (in Spanish). June 2, 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-06-07. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Suspenden clases en Chiapas por posible huracán" [Classes suspended in Chiapas for possible hurricane]. La Prensa (in Spanish). June 2, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Oaxaca: suspenden clases 50 municipios por Boris" [Oaxaca: classes suspended for 50 municipalities due to Boris]. El Universal (in Spanish). June 3, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- "Evacuan a 16 mil chiapanecos por tormenta Boris" [16,000 evacuated in Chiapas prior to Boris]. El Universal (in Spanish). June 3, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- "Guatemala confirma la formación de una depresión tropical en el Pacífico" [Guatemala confirms the formation of a tropical depression in the Pacific]. Alaniza Metropolitan News (in Spanish). June 2, 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-06-07. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Supervisan ríos y arroyos ante lluvias en Chiapas" [Rivers and streams monitored for rainfall in Chiapas]. El Universal (in Spanish). June 3, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- "Chiapas reporta saldo blanco ante lluvias de Boris". El Universal (in Spanish). June 4, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- "Inundaciones y un muerto, por lluvias" [Showers, flooding, and deaths]. El Universal (in Spanish). June 4, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- Eric S. Blake (August 21, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Cristina (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- "Guerrero mantiene alerta por lluvias de Cristina". El Universal. June 12, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Guerrero mantiene alerta por lluvias de Cristina". El Universal. June 11, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Reportan inundaciones en Manzanillo por Cristina". El Universal. June 12, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- Richard J. Pasch (March 4, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Douglas (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- Lixion A. Avila (August 8, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Elida (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- John P. Cangialosi (August 31, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Fausto (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- Eric S. Blake (July 13, 2014). "Tropical Weather Outlook" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- Jeff Powell (March 24, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Wali (PDF). Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- Derek Wroe (July 17, 2014). "Tropical Storm Wali Special Discussion Number 2". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Honolulu, Hawaii: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- John L. Beven II; Thomas Birchard (August 19, 2016). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Genevieve (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Robbie J. Berg (October 7, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Hernan (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Tobb B. Kimberlain; Michael J. Brennan (June 12, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Iselle (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Stacy R. Stewart; Christopher Jacobson (February 11, 2016). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Julio (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Daniel P. Brown (November 17, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Karina (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- Eric S. Blake (January 20, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Lowell (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- David A. Zelinsky; Richard J. Pasch (January 30, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Marie (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- Lixion A. Avila (November 25, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Norbert (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- John P. Cangialosi; Todd B. Kimberlain (March 4, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Odile (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- John L. Beven II (February 19, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Sixteen-E (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- Robbie J. Berg (January 24, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Polo (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- "Huracán Polo deja numerosos daños en Guerrero". Altonivel (in Spanish). September 19, 2014. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- Enrique Villagómez (September 22, 2014). "Polo deja daños por más de 100 mdp en Guerrero". El Financiero (in Spanish). Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- Christopher W. Landsea; Todd B. Kimberlain (January 20, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Rachel (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- Stacy R. Stewart (June 20, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Simon (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- Jeff Powell (July 17, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ana (PDF). Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- Kodama (October 15, 2014). "Tropical Storm Ana Advisory Number 10". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Wroe (October 18, 2014). "Hurricane Ana Advisory Number 22". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Powell (October 19, 2014). "Hurricane Ana Advisory Number 25". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Kurtis Lee (October 19, 2014). "Hurricane Ana weakens, moves west of Hawaii". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- "Hurricane Ana Rainfall Totals". Honolulu, Hawaii National Weather Service. October 19, 2014. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014.

- Jim Mendoza (October 21, 2014). "Hurricane triggers sewage spill". WWLP.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-21. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Daniel P. Brown (December 2, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Trudy (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Liliana Alcántara (October 17, 2014). "Emiten zona de alerta por tormenta tropical en Guerrero". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- "Emiten alerta roja para zonas de Guerrero y Oaxaca por Trudy". El Universal (in Spanish). October 18, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Laura Reyes (October 19, 2014). "'Trudy' causa seis muertos tras su paso por Guerrero y Oaxaca". Reuters (in Spanish). CNN México. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- "Restablecido 91% de suministro eléctrico en Guerrero". Notimex (in Spanish). El Financiero. October 19, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- David Vicenteño; Rolando Aguilar (October 19, 2014). "Declaran emergencia en 35 municipios de Guerrero por Trudy". Excélsior (in Spanish). Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- "En emergencia 100 municipios de Oaxaca por la tormenta "Trudy"". Notimex (in Spanish). Economía Hoy. October 21, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Arturo Márquez (October 23, 2014). "Suman 8 muertos en Guerrero por 'Trudy'; comunidades continúan incomunicadas". Noticieros Televisa (in Spanish). Noticieros Televisa. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- "Tormenta Tropical Trudy deja un muerto en Campeche". SDP Noticias (in Spanish). SDP Noticias. October 21, 2014. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Eric S. Blake (January 27, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Vance (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Víctor Blanco (November 6, 2014). ""Vance" causa daños en todo el Estado" (in Spanish). Organización Editorial Mexicana. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- Rosy Gaucín (November 10, 2014). "'Vance' deja daños en 7 municipios de Durango" (in Spanish). El Siglo de Durango. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- "Tropical Cyclone Names". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2013-04-11. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- "Pacific Tropical Cyclone Names" (PHP). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 11, 2013. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- "'Isis' among names removed from UN list of hurricane names". Reuters. April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Antonio Vázquez López (August 25, 2014). "Marie causa la muerte de dos personas en la Costalegre de Jalisco" (in Spanish). Notisistema. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2014 Pacific hurricane season. |