2005 Loganair Islander accident

On 15 March 2005, a Britten-Norman Islander air ambulance, operated by Loganair, crashed off the coast of Scotland, killing both people on board.

Britten Norman Islander in Loganair livery. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 15 March 2005 |

| Summary | Controlled flight into terrain due to fatigue and possible spatial disorientation |

| Site | 7.7 nmi (14.3 km) west-north-west of Campbeltown, Argyll, Scotland 55.486666°N 005.895°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Pilatus Britten-Norman BN2B-26 Islander |

| Operator | Loganair (for Scottish Ambulance Service) |

| Registration | G-BOMG |

| Flight origin | Glasgow Airport |

| Destination | Campbeltown Airport |

| Passengers | 1 (paramedic) |

| Crew | 1 (pilot) |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Survivors | 0 |

The aircraft was en route to Campbeltown Airport in Argyll, Scotland, to pick up a ten-year-old boy with acute abdominal pain, suspected to be appendicitis. After a flight that included many navigational irregularities, the pilot was flying the normal approach, which took the aircraft out to sea before turning back toward the airport. The pilot informed controllers that he had completed the turn, and that was the last transmission received from the aircraft. Investigators conclude the aircraft hit the water a few seconds after that transmission. Both occupants of the aircraft, the pilot and a paramedic seated at his station behind the pilot, were killed. The ensuing investigation concluded that the pilot allowed the aircraft to fly too low, and it descended unchecked into the sea. The pilot was also fatigued, overworked, lacked recent flying practice, and he might have suffered from an undetermined influence, such as disorientation, distraction, or subtle incapacitation, as evidenced by several navigational errors, miscommunications, and mismanagement of his instruments. Although the weather might have precluded a safe landing in Campbeltown, the weather was not a cause of the accident. The patient was eventually driven overland to a Glasgow hospital, where he was treated for a ruptured appendix.

The paramedic's body was found strapped in to his seat with a severe, possibly fatal, head injury from an impact against the back of the pilot's seat in front of him. Despite the death of both occupants of the aircraft, the UK's Air Accidents Investigation Branch, or AAIB, considered the impact survivable by the pilot. Had the paramedic been wearing a shoulder harness, the AAIB concluded it was likely that the paramedic would have survived the impact with the water with little or no injury, though it is possible he might then have succumbed to the cold water. The pilot, whose uninjured body was found nine months after the accident, and who had been wearing a shoulder harness, most likely survived the accident and escaped the aircraft, only to die of hypothermia in the cold water. As a result of this accident, regulations were enacted in 2015 by the European Union (EU) that require all aircraft of similar size that are used to transport passengers to be equipped with a shoulder harness, or "upper torso restraint system" (UTR system), for each passenger seat.

Two more recommendations from the AAIB investigators of this accident were under consideration (as of the end of 2015) by EU regulators. These recommendations would require two pilots for all air ambulance flights and require a radar altimeter or "other independent low height warning device" (such as a GPWS) on all single-pilot public transport flights conducted in limited visibility (i.e., IFR passenger flights).

Background

Loganair and the Scottish Ambulance Service

In 1967, Loganair began operating air ambulances for Scottish Ambulance Service (SAS).[1] In 2005, they were using three dedicated Britten Norman Islander aircraft, including the accident aircraft, to transport patients from hard-to-reach locations throughout the Scottish Highlands and the surrounding islands, flying roughly 2,000 ambulance flights per year. In February 2005 (months before this accident), SAS announced they would be ending their contract with Loganair in October 2006 and replacing them with Gama Aviation, which would provide two fixed-wing aircraft and two helicopters.[2]

1996 accident

Loganair had one previous air ambulance accident, also involving a Britten Norman Islander, on 19 May 1996, in which the pilot was killed, and the two passengers, a physician and a flight nurse, were injured. (In 1996, flights were typically made with a nurse, and sometimes a physician, if needed. The passenger cabin of the Islander was of limited size, and typical of ambulance aircraft, working conditions could be quite cramped with more personnel.[3][4]) This 1996 accident bore similarities to the 2005 accident. It occurred at night with a single fatigued and poorly rested pilot making an approach in difficult weather, though in this case it was a strong and gusting crosswind rather than poor visibility that was the primary meteorological challenge.[5][6]

After successfully transporting the patient from Tingwall Airport in the Shetland Islands to Inverness Airport, the pilot, nurse, and physician were returning to their home base in Tingwall. There was a strong and gusting right crosswind at the runway. The pilot's approach procedure required him to make right turns to line up with the runway. However, these right turns obscured the pilot's view of the runway, and when the pilot made his final right turn, the aircraft had been blown to the left of the runway, too far to make a safe landing. The pilot executed a go-around procedure and attempted another approach. Again, the aircraft was blown far to the left of the runway centreline, and during the final approach turn, the aircraft lost a great deal of altitude, striking the ground 1.5 km short of the runway and approximately 0.3 km to the left of the runway centreline. The AAIB determined that nighttime visibility of the airport environment was inadequate, especially during right crosswind conditions, and recommended the Tingwall Airport add additional ground lighting to aid pilots' ability to acquire the runway during nighttime approaches.[5]

Aircraft

The aircraft was a British built BN2B-26 Islander manufactured by Pilatus Britten-Norman in 1989, registration G-BOMG. It was a high wing design with two wing-mounted Lycoming O-540-E4C5 piston engines, each delivering a rated 260 horsepower to a two-blade variable-pitch propeller. It had fixed tricycle landing gear, with the two main gear bogies (two wheels each) mounted on legs that extend down from the wing, just aft of the engines. It made its first flight on 20 March of that year. It was delivered to the original customer in Germany, FLN Frisia Luftverkehr, on 25 May, and re-registered in Germany as D-IBNF. On 14 August 2002, Loganair purchased the aircraft from FLN and registered it in the UK as G-BOMG.[7] Loganair's chief executive, Jim Cameron, described the Islander as "robust" and "well suited to the vagaries of Scottish weather."[8] Summarizing expert opinion of the Islander, Alastair Dalton of The Scotsman said the aircraft "had a good safety record and had proved versatile in operating from the shortest and roughest Highland runways."[2]

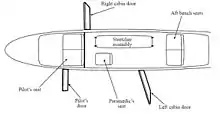

Loganair converted the aircraft into an ambulance after purchasing it from FLN. It had one stretcher, a paramedic seat behind the pilot, two seats in the back of the cabin, and two cockpit seats. The aircraft had three doors, though the right cabin door was difficult to access because it was blocked by the stretcher. The aircraft was equipped with autopilot, and it was certified for single-pilot operation.[6](p10)

The aircraft was equipped with a diagonal shoulder harness for each of the eight passenger seats when it was delivered new to FLN. However, when Loganair converted the aircraft for ambulance use, they installed the same seats and seat belts they used in the rest of their Islander fleet. The shoulder harnesses were designed to attach to a specific type of lap belt, which was different from the lap belts used by Loganair. At the time of the accident, shoulder harnesses were not required for passengers, and Loganair did not retrofit the seat belts or shoulder harnesses to be compatible with each other.[6](p40)

Personnel

The pilot, 40-year-old Guy Henderson of Broxburn, Scotland, had 3,553 hours total flight experience, including 205 in the Islander. His Airline Transport Licence and Class I Medical Certificate were current.[6](p7)[9] Due to flight scheduling and a family vacation, he had not flown for 32 days before the accident.[6](p8) On the day of the accident, Henderson awoke at 0645 h after eight hours of sleep. He was scheduled to begin standby duty from home that evening, lasting overnight, at 2300 h. (Standby duty from home means the pilot must be able to be at the airport, ready for duty, within one hour.) He was called early, at 2136 h, and reported for duty at the airport at 2220 h. There was no indication that the pilot tried to sleep during the day.[6](p9)

Loganair had a requirement that a pilot must have flown within the previous 28 days before being allowed to carry passengers.[6](p38) Therefore, upon his arrival at Glasgow Airport, Henderson was required to take off and land the aircraft one time (a currency flight) before allowing the paramedic to board for the ambulance mission. (Because the paramedic was not involved with flight operations, he was legally considered a passenger.[6](p38)) The pilot made his currency flight by flying one circuit around the airport and returning to the Loganair apron to pick up the paramedic. There was heavy rain during this flight, but it was otherwise uneventful.[6](p4)

The sole passenger on the accident flight was Paramedic John Keith McCreanor, 35, of Paisley, Scotland.[9] He was seated in the paramedic seat, behind the pilot, for the duration of the flight. McCreanor had been a paramedic for twelve years and an employee of SAS for nine years and ten months.[6](p9) He arrived for the flight at 2300 h but had to wait for Henderson to complete his currency flight before boarding.[6](p4)

Mission

The operations officer at Loganair in Glasgow received a call at 2133 h from SAS requesting an air ambulance flight to pick up a ten-year-old boy named Craig McKillop at Campbeltown Airport, who was suffering from severe abdominal pain and suspected appendicitis, and fly him to Glasgow for treatment. The boy's father was scheduled to fly to Glasgow with his son and the paramedic. The requested maximum transfer time was three hours.[2][6](p3)

The flight

Departure and navigation

The flight used the callsign LOGAN AMBULANCE ONE and was given ATC clearance to fly direct to Campbeltown. For unknown reasons, the pilot requested an amended clearance to fly a course that took them west and then southwest toward Campbeltown, avoiding flight over the Isle of Arran, further delaying their expected arrival time. The aircraft was airborne at 2333 h, with one hour remaining in the requested patient transfer time.[6](p4, 47)

The aircraft climbed to its assigned cruising altitude of 6,000 ft (1,829 m) and left controlled airspace. The pilot kept in contact with ATC for information and advisory services. At 2359 h the controller noticed that the aircraft had not made its scheduled left turn toward Campbeltown. The controller asked the pilot to confirm his routing, and he advised the pilot that he was already west of his intended course. The pilot then made a sharp left turn to the southeast, followed by another to the southwest, toward Campbeltown. As the aircraft descended toward Campbeltown, it had not been on its approved course since it left the immediate vicinity of Glasgow.[6](p5, 47–48)

Approach to Campbeltown

When the aircraft was 6.5 nmi (12.0 km) north of the Machrihanish (MAC) VOR (a type of radio navigational beacon near Campbeltown Airport), the pilot requested descent clearance. The controller cleared the aircraft to descend to 3,900 ft (1,189 m) at 2403 h, which was the minimum Sector Safe Altitude (SSA), the lowest altitude that can guarantee safe separation from all terrain and other obstacles in the area.[6](p5, 16, 48) When the aircraft was 4 nmi (7 km) from the MAC VOR, it descended below the SSA to 3,000 ft (914 m). This was the altitude needed to enter the airport's landing pattern, but the descent wasn't required until the aircraft was over the MAC VOR. This early descent below the SSA was described by investigators from the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) as "contrary to safe practise as well as the operator's procedures".[6](p6, 48)

The approach procedure in use for this flight in the low clouds and low visibility conditions that night required the pilot to fly over the MAC VOR at 3,900 ft (1,189 m), then turn west-northwest to fly out over the water, descend to 1,540 ft (469 m) and level off within nine miles, then make a left base turn to fly east, back toward the airport (a teardrop procedure turn), and descend for final approach with the use of the MAC VOR. The pilot was not allowed to descend below 1,540 ft (469 m) until the turn was completed, and then not below 1,045 ft (319 m) unless he had the runway in sight.[6](p16) Once the pilot could see the airport from that altitude, he would be allowed to circle and land on the runway of his choice. This is called a circle-to-land manoeuvre, or sometimes a cloud break procedure. The pilot elected to attempt this circling approach to land on runway 29 instead of landing straight in on runway 11, though the reported clouds at the time would have made a circling approach impossible at the minimum altitude of 1,045 ft (319 m).[6](p6, 16–19)

As the aircraft approached the MAC VOR from the north, the pilot turned right, heading out to sea, 1.0 to 1.5 nmi (1.9 to 2.8 km) before reaching the MAC VOR. This made it difficult to establish the aircraft on the proper outbound course, though this was eventually done. The aircraft began its descent on this outbound leg, but it failed to level off at the minimum altitude of 1,540 ft (469 m). At 2416:22, the last radar contact was recorded with the aircraft 200 ft (61 m) below that altitude, still outbound, and still descending at 1,050 ft (320 m) per minute. At 2418 (approximately 100 seconds after the last radar return) the pilot made his last call to the controller (who did not have radar), saying he had completed his base turn back to the airport. Investigators believe the aircraft hit the water very soon after that transmission.[6](p6, 49–50)

Loss of contact, search and location of wreckage

Five minutes after making its last transmission, the aircraft had not arrived at the airport. The controller tried several times to contact the pilot of the air ambulance, but none were successful. Other personnel in the air traffic control system asked other commercial aircraft in the area to attempt to make radio contact with the Islander. Controllers called the offices of Loganair and SAS, asking them to call the pilot and paramedic on their cell phones. At 2431, which was one minute past the latest time the aircraft could have landed, controllers entered "distress phase", calling out search and rescue personnel.[6](p6–7)

Three lifeboats were dispatched from Northern Ireland to the area where the aircraft was last seen on radar, along with two helicopters from Prestwick and Anglesey and one from the Strathclyde Police (during daytime hours), and HMS Penzance, a Royal Navy minesweeper that was conducting training operations 35 nmi (65 km) away. Coastguard rescue teams conducted searches along the shoreline all night and the next day along with officers from the Strathclyde Police Department. Two investigators from the AAIB were also sent to the scene. Some wreckage of the aircraft was quickly found floating in the water (all three doors, the paramedic's bag, the left main landing gear leg, and other light material), with the main wreckage submerged on the seabed.[6](p25, 32–33)[10][11] The wreckage was 7.7 nmi (14.3 km) west-northwest of the Campbeltown airport. The fuselage had broken into three main sections: front, centre, and rear. The centre section included the wing. The engines and propellers had been torn from the wings on impact. The paramedic's body was found strapped to his seat. The pilot's body was not found in the vicinity of the debris field.[6](p7, 25)

When it became clear that the air ambulance would not be arriving, the patient who was to be flown to Glasgow on G-BOMG was instead transported by road to the Royal Hospital for Sick Children at Yorkhill, where he underwent surgery to treat a ruptured appendix.[2]

Investigation

Wreckage

Floating debris was collected in the early morning hours after the accident. Two days after the accident, officials had established a one mile exclusion zone against fishing activities near the accident site, and the AAIB had requested specialized deep water recovery equipment to recover the wreckage and, they hoped, the bodies of the pilot and paramedic.[10] Six days later the diving support vessel Seaway Osprey arrived on the scene of the accident with remotely operated vehicles (ROV's) and saturation divers capable of manually recovering debris. Within twelve hours all major components of the aircraft had been recovered except for the left wingtip, which was discovered on 2 May 2005, in a trawler's fishing net about 2.5 nmi (4.6 km) from the debris field.[6](p25) The wreckage was brought to the AAIB's hangar at RAF Machrihanish (on which Campbeltown Airport was located at the time of the accident) for analysis.[2]

All of the primary structure was recovered from the seabed. Controls were trimmed near the neutral position. The flaps were in the "UP" position (i.e., retracted). Investigators found no evidence that the controls were jammed. The left main landing gear leg had become separated during the impact, and the right gear leg was bent aft. The nose gear was bent aft and to the right. Both propellers were recovered and showed similar damage. Both engines were stripped down and examined. They were found to be in similar condition, with valves and other moving parts in good shape. Both engines could be turned when the spark plugs were removed. Both engines, with propellers attached, were found at the northern end of the debris field.[6](p25–28)

The cockpit area of the Islander had not suffered significant damage, and there was sufficient space for the pilot to survive. The pilot's seat belt and shoulder harness were found undamaged and unbuckled, with all stitching intact and the buckle still functional. There was no sign of impact on the controls or the instrument panel.[6](p33) Both fuel tanks contained a significant amount of fuel, which investigators calculated to be approximately 100 US gallons in each of the two wing tanks, and the fuel selector valve was in the correct position.[6](p29) Several instruments were damaged by the impact or by the pressure and corrosion from sitting on the seabed for six days. The aircraft's horizontal situation indicator, or HSI (a navigational instrument to direct the pilot to or from ground-based navigation aids, including the MAC VOR), was not set properly for the approach. The instrument's course selector was set to 103°, though the approach called for a setting of 115°. A second device on the HSI, called the "heading bug", is a prominent marker for the pilot to set to the desired heading so that when the aircraft is flying that heading, the bug is at the top of the instrument's display and aligned with a vertical white line. The heading bug on the HSI was set to 157°. A second instrument situated below the HSI and capable of the same VOR navigation, called the omni bearing indicator (OBI), was also set incorrectly to 309° when it too should have been set to 115°.[6](p29–30, 51–52)

Analysis

All wreckage was found along a 209-metre long, 50-metre wide section of the seabed at a depth of 78 metres. Investigators found no evidence of structural failure inflight. The damage to the aircraft was roughly symmetrical left-to-right, indicating the aircraft was close to wings-level flight on impact. The separation of the left landing gear leg compared to the bending of the right leg suggested to investigators that impact with the water happened with the left wing slightly lower than the right, as the left gear was the more damaged, and therefore subject to more force against the water. When the left wingtip contacted the water, investigators conclude that the aircraft cartwheeled, bringing the right wing down into the water with great force, which they report as being consistent with the nose gear being bent to the right as well as aft. The pattern of damage to the nose and the underside of the fuselage suggests the aircraft was in a slightly nose-down attitude, as if in a normal descent. Nearly neutral trim settings indicated the pilot was not trying to compensate for some abnormal flying condition, such as an engine failure or flight control problems. The pitch trim was set to a slight nose-down attitude, which the aircraft manufacturer calculated to indicate stable flight at 110–120 kn. This is consistent with investigators' calculations based on the damage to the aircraft that it had been moving at 90–130 kn at impact. Damage to the propeller blades is consistent with both of them turning and similar engine power being delivered to them. The amount of power being delivered to the propellers could not be determined. Therefore, it remains possible that ice had accumulated in the carburetors and reduced engine power. Although meteorological conditions were favorable for carburetor icing, and the carburetor heat levers were in the "OFF" position, loss of engine power is not consistent with the speed and shallow angle of impact calculated from the wreckage. Analysis of the engines verified that carburetor heat was not being used at the time of the accident.[6](p27–28, 45–47) The AAIB concluded its analysis of the wreckage with the following statement:

In summary, the aircraft appears to have hit the sea in a controlled flight attitude with symmetric power and no evidence of a technical fault could be found that might explain the flight into the sea.

Weather and environment

Although clouds extended down as low as 300 to 400 ft (91 to 122 m) above the sea surface and surface visibility had fallen to 1,500–2,500 meters at Campeltown Airport, the wind was from the west at 12 knots, and the aircraft was below the freezing level (reported at 6,500 ft (1,981 m)).[6](pp12,14) Conditions at the time of the accident made it possible for ice to form in the carburetors, and carburetor heat was not applied to counteract this possibility, but there was no sign that the engine function was impaired.[6](pp27, 28, 46) The switches for pitot and stall warning probe heating, and for propeller de‑icing were selected ON. The switches for airframe de-icing, heated windshield and for the ice inspection lamp were selected OFF.[6](p31)

Analysis

Low clouds, deteriorating visibility, and winds that favored Runway 29 in Campbeltown, which did not have an instrument approach procedure necessary for landing in such conditions as were forecast for the expected arrival time, posed serious challenges to making a safe landing in Campbeltown. As G-BOMG neared its destination, conditions were worsening. The pilot chose to follow the instrument approach procedure for Runway 11 until he saw the airport, at which point he would circle the airport to land on Runway 29. To perform this manoeuvre, the pilot was not permitted to descend below an altitude of 1,045 ft (319 m). However, the weather reports the pilot received when he departed and others he received while en route show the cloud base was down to 400 ft (122 m) ("broken" cloud layer). This was acceptable for an approach to Runway 11, but not for the circling manoeuvre to Runway 29. At the same time, the wind had increased from 8 kn to 15 kn in Campbeltown, making a landing on Runway 11 increasingly difficult, with significant crosswind and tailwind components. Four minutes before the accident, the controller in Campbeltown advised the pilot that there were now a "few" clouds at 300 ft (91 m) as well as the broken layer at 400 ft (122 m). For the duration of the flight, the pilot likely had very little visual contact with the ground due to being in or over clouds, or out over water in low visibility. As the aircraft descended through the cloud base, the pilot likely had no visual cue that he was below the clouds because the aircraft was about 7 nmi (13 km) out to sea and visibility was reported as 1,500 m (4,921 ft). The pilot of a search and rescue helicopter later commented that the sea surface that night would have provided the pilot with little or no visual cues about the aircraft's dangerously low altitude.[6](pp13–14, 53–54)

Human factors

The pilot awoke at 6:45 AM on the day of the accident. Knowing he was on call duty overnight, he apparently took no rest any time during that day or evening. The AAIB acknowledges it can be difficult for a well rested person to sleep during the daytime, and they note that quiet rest is the best some can achieve, but they also point out that 16–17 hours of continuous wakefulness is associated with diminished performance.[6](p55) Single-pilot IFR operations place a heavy workload on the pilot. That workload increases as the pilot begins the approach phase of the flight. During the approach phase, the pilot announced his intention to land on Runway 25, though he knew the actual runway was 29. The AAIB's human factors analysis suggests this specific type of error might be a significant indicator that the pilot's stress level had increased to the point where it began to further diminish his ability to cope with the heavy workload. They list several potential yet unknown causes for the increase in stress, such as disorientation or an undeclared emergency.[6](p56) Concerning the pilot's performance, the AAIB summarizes:

The combined effects of fatigue, possible over-load and lack of recent flying practise would have caused the pilot's performance to become more variable, especially in tasks that required sustained attention, such as precision instrument flying... If, as is probable, the last transmission was made very shortly before the accident, it indicates that the pilot's situational awareness may have been seriously degraded, as he was therefore unaware of the aircraft's very low altitude... Although there are signs of overload and fatigue, it is unlikely that the pilot became so focused on one aspect of flying the aircraft that he neglected to monitor the aircraft's altitude for a protracted period. It is therefore possible that a further factor such as distraction or disorientation may have played a part.[6](pp57–58)

Postmortem examinations

The body of the pilot was found nine months after the accident by a fishing vessel four miles off the coast in Machrihanish Bay. No obvious internal or external injuries could be detected, nor were there any bone fractures. Because of the condition of the body when it was recovered, it was not possible to determine the cause of death.[6](p31) The body of the paramedic was recovered, still restrained in the seat by his undamaged lap belt, during search and rescue operations six days after the accident. The paramedic had suffered a major head injury from a frontal impact with the back of the pilot's seat. The paramedic "almost certainly" lost consciousness instantly, and the head injury was potentially fatal, but changes in the lungs showed the cause of death to be drowning.[6](pp32–33)

Paramedic's seat belt

To determine the likely cause of the paramedic's head injury, the AAIB requested that Loganair have a man of the same height as the paramedic sit in the paramedic's seat of another of their Islander air ambulances, fasten his seat belt, and lean fully forward to see what obstructions might be encountered. The subject's head came close to the back of the pilot's seat but did not contact it. However, under rapid deceleration, or had the seat belt been slightly looser, his head would have contacted the back of the pilot's seat.[6](pp33–34)

Enroute navigation

Navigation charts used by pilots in the area warn that, because of terrain, the MAC VOR is unreliable for aircraft below 9,000 ft (2,743 m) or farther than 20 nmi (37 km) in the direction from which G-BOMG was navigating toward Campbeltown.[6](pp18–19) The AAIB conducted a test flight in a similar Islander aircraft along the same route flown by G-BOMG. Despite the warnings on the navigation charts, the test aircraft was able to navigate by using the MAC VOR during the entire flight. However, the MAC VOR is also equipped with distance measuring equipment, or DME, which provides a means for pilots to know the distance between their aircraft and the VOR/DME station. On the test flight, the DME signal was not received until the aircraft was 22 nmi (41 km) from the MAC VOR.[6](pp34–35)

Approach radar coverage

After the enroute navigation test flight was completed, the AAIB's test pilot flew several approaches to Campbeltown Airport with the same aircraft while investigators monitored its position on the radar equipment that was used the night of the accident. When the test aircraft flew the approach as indicated on the navigation chart that was found clipped to the pilot's control wheel, there was a small gap in radar coverage when the aircraft was at its most distant point from the airport, beginning at 10.1 nmi (18.7 km) and ending on the return segment at 9.4 nmi (17.4 km) from the MAC VOR. Other trials were conducted at lower altitudes, and in those trials the coverage gap was widened considerably. Investigators tried approaches at low and descending altitudes involving a steeper left turn to 157° (where the heading bug was set on the HSI), and then flying that heading until intercepting the correct course to the MAC VOR. When this track was flown at 1,400 ft (427 m), the last radar contact was at 7.9 nmi (14.6 km) from the MAC VOR. The last radar contact with the accident flight was at 8.1 nmi (15 km) from the MAC VOR, at an altitude of 1,340 ft (408 m). Flying this track with the accident flight's known and projected descent profile brought the test aircraft to within 0.2 nmi (0.4 km) of the crash site at an altitude of 200 ft (61 m), which was within the margin of error for the differences in wind on the day of the accident and on the day of the test flight.[6](p25, 34–36)

Selected findings

The AAIB published 47 separate findings based on their investigation. Below are some of the findings that have greater historical significance because they bear directly on the causes of the accident or the causes of death of the pilot and paramedic, or because they served as a basis for changes in the air transport industry.[note 1]

- "No evidence of a technical fault was found that could explain the accident, though a malfunction affecting critical flight instruments could not be entirely ruled out."[6](p60)

- Although a safe landing at Campbeltown was in doubt, the pilot was authorised to make an approach. Weather at his two designated alternate landing airports (Glasgow and Prestwick) was good in case the plane needed to divert.[6](pp63–64)

- "The presence of a second pilot may have prevented the accident."[6](p64)

- "Had the aircraft been equipped with a radio altimeter, or other electronic low height warning device, which was correctly set to warn of a low height situation, the accident may not have occurred."[6](p64)

- "It is probable that the pilot was suffering, at least to some extent, from the affects [sic] of fatigue."[6](p64)

- "The pilot may have been operating under high workload, or even overload, conditions in the latter stages of the flight, which may have degraded his situational awareness."[6](p64)

- "The paramedic was probably rendered unconscious in the impact when his head hit the pilot's seat in front due to the lack of upper torso restraint."[6](p65)

- "Average survival time in the sea, at a temperature of 9 °C, would have been no more than one hour."[6](p66)

Causal factors

The AAIB determined the following three causal factors, which are quoted directly from their report.[6](p66)

- "The pilot allowed the aircraft to descend below the minimum altitude for the aircraft's position on the approach procedure, and this descent probably continued unchecked until the aircraft flew into the sea."

- "A combination of fatigue, workload and lack of recent flying practise probably contributed to the pilot's reduced performance."

- "The pilot may have been subject to an undetermined influence such as disorientation, distraction, or a subtle incapacitation, which affected the pilot's ability to safely control the aircraft's flightpath."

Safety recommendations

The AAIB made three safety recommendations to UK and European regulators based on the findings of their investigation of this accident. They are quoted below.[6](p67)

2006-101: "The European Aviation Safety Agency and Joint Aviation Authorities should review the UK Civil Aviation Authority's proposal to mandate the fitment of Upper Torso Restraints on all seats of existing Transport Category (Passenger) aeroplanes below 5,700 kg being operated for public transport, and consider creating regulation to implement the intent of the proposal."

2006-102: "Considering the unique circumstances of air ambulance flights, the Civil Aviation Authority, in conjunction with the Joint Aviation Authorities should review the circumstances in which a second pilot is required for public transport flights operating air ambulance services."

2006-103: "The Civil Aviation Authority, in conjunction with the Joint Aviation Authorities, should consider mandating the carriage of a radio altimeter, or other independent low height warning device, for public transport IFR flights operating with a single pilot."

Aftermath

Loganair operations

Following this accident, Loganair installed shoulder harnesses and compatible lap belts on one of its two remaining air ambulances at the request of the SAS, though Loganair's contract with the SAS was nearing its expiration and was not going to be renewed, as had been announced before the accident.[2][6](p59) As of January, 2016, Loganair continued to operate two Britten-Norman Islanders in its fleet, convertible for passenger or cargo service.[12]

Endorsements of the safety recommendations

Pilot Guy Henderson's fiancée, Lorne Blyth, strongly endorsed two of the AAIB's recommendations when the accident report was published, saying, "I feel very strongly that everything possible should be done to ensure that future tragedies are prevented and therefore call on Transport Secretary Douglas Alexander to implement the recommendations from the AAIB report."[13] Blyth added, "Had a second pilot been on the aircraft, or had the aircraft been equipped with a radio altimeter or other low-height warning device, the accident may not have happened."[14] Blyth also called for personal locator beacons for aircrew on such flights, which might have led to a quicker recovery of her fiancé's body. "These are inexpensive but highly effective. Such equipment may not have saved Guy's life, but it almost certainly would have led to the recovery of his body in days rather than months," said Blyth.[13]

The secretary general for the British Airline Pilots' Association (BALPA), Jim McAuslan, said of the AAIB's recommendations, "Had there been a second pilot, he or she would have almost certainly prevented the aircraft's descent into the sea and those on board would be alive today."[14] Stating the union's position on the matter, McAuslan said "We are demanding that air ambulances always have two pilots, not one." He added, "Six years ago, following a similar accident, the AAIB recommended a review of the circumstances in which a second pilot is required for air ambulance flights. But no action was taken." He also endorsed a change to regulations that would make shoulder harnesses mandatory.[13]

Shoulder harnesses

The UK's Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) had conducted a study on the benefit of requiring upper torso restraints (UTR, i.e., shoulder harnesses) in passenger seats of aircraft weighing less than 5,670 kg in response to a safety recommendation arising from the investigation of a 1999 accident involving a Cessna Titan near Glasgow.[6](ppA1–A5)[15](p68) As a result of that study, the CAA changed its regulations to require shoulder harnesses for passengers on all aircraft registered after 1 February 1989, if that aircraft has a maximum takeoff weight of 5,700 or less and 9 passenger seats or fewer.[6](pA2) The CAA also forwarded a recommendation to the Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA) of Europe, recommending that European regulators adopt a similar standard.[6](pA5) However, at the time of the Loganair accident, the JAA had not acted on the recommendation.[6](p59) Although the UK regulation covered the accident aircraft (it was first certified in May, 1989), Loganair had obtained an exemption from the CAA concerning this issue.[6](p59)

As a result of this accident, the AAIB issued safety recommendation 2006-101 (regarding shoulder harnesses) and a copy of their earlier study to the JAA and to the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), which would take over from the JAA as the primary European regulatory body over a period of several years, beginning before the accident. While considering this recommendation, the EASA took the interim step of issuing its own Safety Information Bulletin (SIB 2008–24), which advised the air transport community of the CAA's earlier study and of the benefits of shoulder harnesses.[16](p26)[17] In 2011, the EASA published its opinion that the requirement recommended by the AAIB following the Loganair accident that shoulder harnesses should be mandatory for each passenger seat in all commercial air transport aircraft weighing less than 5,700 kg, regardless of when the aircraft was first registered.[18](p103)[19](p88) The European Commission accepted the EASA opinion, and new regulations requiring shoulder harnesses as described in the AAIB's safety recommendation 2006-101 became law for commercial air transport operators in Europe.[20]

Requiring two pilots and automated height warnings

The other two safety recommendations (2006-102 and 2006-103, requiring two pilots on all air ambulance flights and requiring radar altimeters or other height-sensing devices on single-pilot air-transport aircraft) were addressed to the CAA and the JAA only. The JAA responded in 2007 with a letter saying the JAA was "no longer in a position to undertake any work on these topics and responsibility must now lie with EASA." Later that year the AAIB wrote to the EASA to request that they consider safety recommendations 2006-102 and 2006-103 as well. (Safety recommendation 2006-101 had already been addressed to the EASA, so no further action was required.)[21](pp39–40) The EASA responded in 2009 that it had accepted both recommendations into its 4-year Rulemaking Programme.[22](pp59–60) However, the recommendations were passed from one 4-Year Rulemaking Programme to the next.[23] The 2013–2016 EASA status report on its 4-year Rulemaking Programme indicates they expect to issue an opinion on 2006-102 (requiring two pilots on air ambulance flights) by 2019 and a decision by 2020. An opinion on 2006-103 (requiring automatic height-sensing devices) is scheduled to be given by 2018, with a decision made by 2019.[24]

Notes

- The first in this list is a quote from a page in the Analysis section of the investigation report that summarizes several findings. The second in this list is also a statement summarizing several of the findings, though not a quote from the report. The rest are specific findings as quoted from the AAIB report.

References

- Loganair. "Brief History". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Dalton, Alastair (16 March 2005). "Family's tribute to pilot and paramedic lost in crash". The Scotsman. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Burgess, Carol J. (July 1995). "Emergency care in the Shetland Islands". Accident and Emergency Nursing. 3 (3): 160–161. doi:10.1016/S0965-2302(95)80013-1.

- Martin, T. E. (June 2003). "Practical aspects of aeromedical transport". Current Anaesthesia & Critical Care. 14 (3): 141–148. doi:10.1016/S0953-7112(03)00017-6.

- Air Accidents Investigation Branch. "BN2A-26 Islander, G-BEDZ, 19 May 1996". GOV.UK. Department for Transport, Air Accidents Investigation Branch. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Formal Report AAR 2/2006 Report on the accident to Pilatus Britten-Norman BN2B-26 Islander, G-BOMG, West-north-west of Campbeltown Airport, Scotland, on 15 March 2005. 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Aviation Safety Network. "Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Seenan, Gerard (15 May 2005). "Inquiry into crash of air ambulance". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- BBC News (16 March 2005). "Mercy air crew search called off". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "Deep water craft needed to find plane". The Scotsman. 17 March 2005. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- PTaylor (15 March 2005). "Two die in air ambulance crash". News & Star. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Loganair. "Loganair Aircraft". Loganair official website. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Woodman, Peter (13 November 2006). "Fatal Scottish Air Ambulance Crash Tied to Fatigue". EMSWorld. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "Crash pilot's widow in plea to ministers over plane safety". The Scotsman. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Air Accidents Investigation Branch. "Report No: 2/2001. Report on the accident to Cessna 404 Titan, G-ILGW, near Glasgow Airport on 3 September 1999". GOV.UK. Department for Transport, Air Accidents Investigation Branch. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Air Accidents Investigation Branch. "Progress Report 2009". GOV.UK. Department for Transport, Air Accidents Investigation Branch. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- European Aviation Safety Agency. "Safety Information Bulletin 2008–24". European Aviation Safety Agency. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- European Aviation Safety Agency. "OPINION NO 04/2011 OF THE EUROPEAN AVIATION SAFETY AGENCY of 1 June 2011 for a Commission Regulation establishing the Implementing Rules for air operations" (PDF). European Aviation Safety Agency. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- European Aviation Safety Agency. "2011 Annual Safety Recommendations review" (PDF). European Aviation Safety Agency. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- European Commission (25 October 2012). "COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) No 965/2012: CAT.IDE.A.205 Seats, seat safety belts, restraint systems and child restraint devices". Official Journal of the European Union. 965/2012: L/296 116. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Air Accidents Investigation Branch. "Progress Report 2007". GOV.UK. Department for Transport, Air Accidents Investigation Branch. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- European Aviation Safety Agency. "2009 Annual Safety Recommendations review" (PDF). European Aviation Safety Agency. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- EASA (2012). Inventory Rulemaking Programme 2012–2015 (PDF). Brussels: European Aviation Safety Agency. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- EASA (2013). 4-Year Rulemaking Programme 2013–2016 (PDF). Brussels: European Aviation Safety Agency. Retrieved 23 January 2016.