1946 Punjab Provincial Assembly election

Elections to the Punjab Legislative Assembly were held in January 1946 as part of the 1946 Indian provincial elections.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

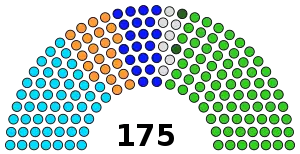

175 seats of The Punjab Assembly 88 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Punjab Provincial Assembly 1946-1947 | |

|---|---|

| Structure | |

| Seats | 175 (88 seats needed for majority) |

| |

Political groups | Government (100)

Opposition (75) |

| Elections | |

| First-past-the-post | |

Campaign

The Unionist Party contested the election under the leadership of Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana but the party stood at fourth place. To stop the Muslim League to form the government in Punjab Indian National Congress and Shiromani Akali Dal extended their support to Unionist Party. Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana resigned on 2 March 1947 against the decision of Partition of India.

The Punjab province was a key battleground in the 1946 Indian provincial elections. The Punjab had a slight Muslim majority, and local politics had been dominated by the secular Unionist Party and its longtime leader Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan. The Unionists had built a formidable power base in the Punjabi countryside through policies of patronage allowing them to retain the loyalty of landlords and pirs who exerted significant local influence.[1] For the Muslim League to claim to represent the Muslim vote, they would need to win over the majority of the seats held by the Unionists. Following the death of Sir Sikander in 1942, and bidding to overcome their dismal showing in the elections of 1937, the Muslim League intensified campaigning throughout rural and urban Punjab.[2]

A major thrust of the Muslim's League's campaign was the increased use of religious symbolism. Activists were advised to join in communal prayers when visiting villages, and gain permission to hold meetings after the Friday prayers.[1] The Quran became a symbol of the Muslim League at rallies, and pledges to vote were made on it.[1] Students, a key component of the Muslim League's activists, were trained to appeal to the electorate on communal lines, and at the peak of student activity during the Christmas holidays of 1945, 250 students from Aligarh were invited to campaign in the province along with 1550 members of the Punjab Muslim Student's Federation.[1] A key achievement of their religious propaganda came in enticing Muslim Jats and Gujjars from their intercommunal tribal loyalties.[1] In response, the Unionists attempted to counter the growing religious appeal of the Muslim League by introducing religious symbolism into their own campaign, but with no student activists to rely upon and dwindling support amongst the landlords, their attempts met with little success.

To further their religious appeal, the Muslim League also launched efforts to entice Pirs towards their cause. Pirs dominated the religious landscape, and were individuals who claimed to inherit religious authority from Sufi Saints who had proselytised in the region since the eleventh century.[1] By the twentieth century, most Punjabi Muslims offered allegiance to a Pir as their religious guide, thus providing them considerable political influence.[1] The Unionists had successfully cultivated the support of Pirs to achieve success in the 1937 elections, and the Muslim League now attempted to replicate their method of doing so. To do so, the Muslim League created the Masheikh Committee, used Urs ceremonies and shrines for meetings and rallies and encouraged fatwas urging support for the Muslim League.[1] Reasons for the pirs switching allegiance varied. For the Gilani Pirs of Multan the over-riding factor was local longstanding factional rivalries, whilst for many others a shrines size and relationship with the government dictated its allegiance.[1]

Despite the Muslim League's aim to foster a united Muslim loyalty, it also recognised the need to better exploit the biradari network and appeal to primordial tribal loyalties. In 1946 it held a special Gujjar conference intending to appeal to all Muslim Gujjars, and lifted its ban on Jahanara Shahnawaz with the hope of appealing to Arain constituencies.[1] Appealing to biradari ties enabled the Muslim League to accelerate support amongst landlords, and in turn use the landlords client-patron economic relationship with their tenants to guarantee votes for the forthcoming election.[1]

A separate strategy of the Muslim League was to exploit the economic slump suffered in the Punjab as a result of the Second World War.[1] The Punjab had supplied 27 per cent of the Indian Army recruits during the war, constituting 800,000 men, and representing a significant part of the electorate. By 1946, less than 20 per cent of those servicemen returning home had found employment.[1] This in part was exacerbated by the speedy end to the war in Asia, which caught the Unionist's by surprise, and meant their plans to deploy servicemen to work in canal colonies were not yet ready.[1] The Muslim League took advantage of this weakness and followed Congress's example of providing work to servicemen within its organisation.[1] The Muslim League's ability to offer an alternative to the Unionist government, namely the promise of Pakistan as an answer to the economic dislocation suffered by Punjabi villagers, was identified as a key issue for the election.[1]

On the eve of the elections, the political landscape in the Punjab was finely poised, and the Muslim League offered a credible alternative to the Unionist Party. The transformation itself had been rapid, as most landlords and pirs had not switched allegiance until after 1944.[1] The breakdown of talks between the Punjab Premier, Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana and Muhammad Ali Jinnah in late 1944 had meant many Muslims were now forced to choose between the two parties at the forthcoming election.[1] A further blow for the Unionists came with death of its leading statesman Sir Chhotu Ram in early 1945.

Results

In the Punjab, the concerted effort of the Muslim League led to its greatest success, winning 75 seats of the total Muslim seats and becoming the largest single party in the Assembly. The Unionist Party suffered heavy losses winning only 20 seats in total. The Congress was the second largest party, winning 43 seats, whilst the Sikh centric Akali Dal came third with 22 seats.[2]

Government formation

A coalition consisting of the Congress, Unionist Party and the Akalis was formed in Punjab.[3]

Ishtiaq Ahmed[4] has given a well documented account of how the Coalition Government in the United Punjab collapsed as a result of a massive campaign launched by the then Punjab Muslim League. AIML (Punjab) deemed the coalition government as a 'non-representative' government and thought it was their right to bring such government down (notwithstanding the fact that it was a legal and democratically elected government). AIML (P) called for a 'Civil Disobedience' movement (which was fully backed by Mr. Jinnah and Mr. Liaqat Ali Khan, after they had failed to enlist Sikh's support to help form an AIML led government in Punjab). This led to bloody communal riots in Punjab during the later part of 1946. By early 1947, Law and order situation in the Province came to such a point where civil life was utterly paralysed. It was under such circumstances that the coalition Punjab Premier (Chief Minister) Mr. Khizer Haya Tiwana was forced to resign, on 2 March 1947. His cabinet was dissolved the same day. As there was no hope left for any other government to be formed to take the place of the Khizer government, the then Punjab Governor Sir Evan Jenkins imposed Governor's rule in Punjab on 5 March which continued up to the partition day, that is 15 August 1947. Akali-Dall Sikkhs who, with 22 seats, were major stake-holders in the coalition along with Congress(51) and the Unionist Party (20), were infuriated over the dissolution of the Khizer Government. It was in this backdrop that on 3 March 1947, Akali Sikh leader Master Tara Singh brandished his Kirpan outside Punjab Assembly saying openly 'down with Pakistan and blood be to the one who demands it'. From this day on wards, Punjab was engulfed in such bloodied communal riots that the history had never witnessed before. Eventually, Punjab had to be partitioned into the Indian and Pakistani Punjab. In the process, over a million of innocent people were massacred, millions were forced to cross-over and to become refugees while thousands of women were abducted, raped and killed, across all religious communities in Punjab.

Interim Assembly (1947-1951)

On 3 June 1947 the assembly which was elected in 1946 divided into two parts. One was West Punjab Assembly and other was East Punjab Assembly to decide whether or not the province of Punjab be partitioned. After voting on both sides, partition was decided. Consequently, the existing Punjab Legislative Assembly was also divided into West Punjab Legislative Assembly and the East Punjab Legislative Assembly. The sitting members belonging to the Western Section subsequently became the members of the new Assembly renamed as the West Punjab Legislative Assembly.

East Punjab

The sitting members belonging to the Eastern Section subsequently became the members of the new Assembly renamed as the East Punjab Legislative Assembly. The members which were elected in 1946 election on the ticket of Shiromani Akali Dal and Unionist Party after Partition all joined the Indian National Congress. There were a total of 79 members.[5]

On 15 August 1947 Gopi Chand Bhargava was elected the Chief Minister of East Punjab by the members of the interim assembly.

On 1 November 1947, the interim assembly sat for the first time. Kapur Singh was elected Speaker on the same day and 2 days later (on 3 November), Thakur Panchan Chand was elected Deputy Speaker.

On 6 April 1949 Bhim Sen Sachar and Pratap Singh Kairon with other members moved Motion of no confidence against Gopi Chand Bhargava. Dr. Bhargava failed to secure motion by one vote. No confidence motion was carried by 40 votes in favour and 39 against.[6]

On the same day Bhim Sen Sachar elected the leader of congress assembly party. He took the oath of Chief Minister of Punjab on 13 April 1949. On the issue of corruption Sachar resigned from the post and on next day on 18 October 1949, Bhargava took charge of Chief Minister of Punjab.

Thakur Panchan Chand resigned from the post of Deputy Speaker on 20 March 1951. On 26 March 1951 Smt. Shanno Devi elected Deputy Speaker. Interim Assembly was dissolved on 20 June 1951.

West Punjab

Iftikhar Hussain Khan Mamdot became the first chief minister of West Punjab.

References

- Talbot, I. A. (1980). "The 1946 Punjab Elections". Modern Asian Studies. 14 (1): 65–91. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00012178. JSTOR 312214.

- W. W. J. (1946). "The Indian Elections – 1946". The World Today. 2 (4): 167–175. JSTOR 40391905.

- Joseph E. Schwartzberg. "Schwartzberg Atlas". A Historical Atlas of South Asia. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Ishtiaq Ahmed (2018). The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed: Unraveling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First Person Accounts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-940659-3.

- page xxviii-xxix of Punjab Vidhan Sabha Compendium Archived 2018-09-25 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 12 January 2019.

- Turmoil in Punjab Politics. pp.27