1944 Great Atlantic hurricane

The 1944 Great Atlantic hurricane was a destructive and powerful tropical cyclone that swept across a large portion of the United States East Coast in September 1944. Impacts were most significant in New England, though significant effects were also felt along the Outer Banks, Mid-Atlantic states, and the Canadian Maritimes. Due to its ferocity and path, the storm drew comparisons to the 1938 Long Island Express, known as one of the worst storms in New England history.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

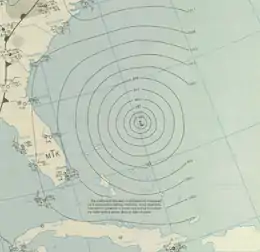

Surface weather analysis of the storm at peak intensity on September 13 | |

| Formed | September 9, 1944 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 16, 1944 |

| (Extratropical after 12:00 UTC September 15) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | ≤ 933 mbar (hPa); 27.55 inHg |

| Fatalities | 300–400, primarily at sea |

| Damage | $100 million (1944 USD) |

| Areas affected | United States East Coast (especially New England), Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 1944 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Though the precursor to the 1944 hurricane was first identified well east of the Lesser Antilles on September 4, the disturbance only became well organized to be considered a tropical cyclone on September 9 northeast of the Virgin Islands. Tracking west-northwest, the storm gradually intensified and reached peak intensity as a Category 4-equivalent hurricane on September 13 north of the Bahamas after curving northward. A day later, the storm passed by the Outer Banks and later made landfall on Long Island and Rhode Island as a weaker hurricane on September 15. The storm eventually transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, after which it continued moving northeast before merging with another extratropical system off of Greenland on September 16.

Meteorological history

The origins of the 1944 hurricane can be traced back to a tropical wave first identified well east of the Lesser Antilles on September 4. Over the next few days, the disturbance slowly traversed west-northwestward without producing any significant weather that would hint at tropical cyclogenesis. On September 7, an area of low pressure, albeit disorganized, formed in association with the tropical wave east of Barbados.[1] The following day, the barometric depression became more well-defined, prompting the Weather Bureau in San Juan, Puerto Rico to issue advisories on the tropical disturbance. As a result of the sparseness of available surface observations east of the Lesser Antilles, a reconnaissance flight was dispatched to investigate the storm late on September 9; the flight reported that the disturbance had strengthened into a newly formed but fully-fledged hurricane.[2] Due to the seemingly rapid development of the storm, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project concluded that the storm likely began earlier and as a weaker system; thus, HURDAT—the official track database for hurricanes in the North Atlantic dating back to 1851—lists the tropical cyclone as having begun a tropical storm with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) at 06:00 UTC on September 9.[3]

After formation, the tropical cyclone gradually intensified as it slowly moved west-northwestward, reaching the threshold for hurricane intensity at 06:00 UTC on September 10 while north of the Virgin Islands. Strengthening continued thereafter, and by September 12, the storm reached an intensity equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Later that day, the cyclone strengthened further into a Category 4-equivalent and was given the moniker of "Great Atlantic hurricane" by the Weather Bureau in Miami, Florida.[2][3] Concurrently, the tropical cyclone began to curve and accelerate towards the north.[2] At 12:00 UTC on September 13, the hurricane reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 145 mph (230 km/h),[3] and five hours later, a ship documented a minimum barometric pressure of 933 mbar (hPa; 27.55 inHg). The storm's pressure may have been lower at the time as it is unknown whether or not the observation took place in the eye, though the 909 mbar (hPa; 26.85 inHg) pressure suggested by meteorologist Ivan Ray Tannehill was considered too low.[1]

The hurricane began to gradually weaken after reaching peak intensity on September 13.[3] In the morning hours of September 14,[2] the storm passed just east of Cape Hatteras and eastern Virginia as a small but powerful hurricane with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h).[1] Afterwards, the cyclone curved slightly further towards the northeast and continued to accelerate;[2] at 02:00 UTC on September 15, the hurricane made landfall near Southampton in eastern Long Island with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h).[1] The storm then crossed the island and Long Island Sound before making a second landfall two hours later near Point Judith, Rhode Island as a slightly weaker storm with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h).[1][2] After crossing Rhode Island and Massachusetts, the tropical system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone off the coast of Maine on September 15;[1] these extratropical remnants continued to track towards the northeast and across the Canadian Maritimes before they were last noted merging with another extratropical cyclone off of Greenland at 12:00 UTC on September 16.[2][3]

Preparations

Upon being designated a tropical cyclone, the Weather Bureau began advising extreme caution to shipping within the expected path of the hurricane.[4] Precaution was also urged in the eastern Bahamas.[5] The first hurricane warning issued by the Weather Bureau in association with the storm was for the northern Bahamas on September 12. In Miami, Florida, the American Red Cross began preparing its resources for a potential regional calamity; however, the Weather Bureau did not necessarily anticipate the storm striking Miami.[6] Royal Air Force aircraft stationed in Nassau were flown to Miami in order to avoid the storm.[7] Although tropical cyclone naming was not in practice at the time,[8] the Weather Bureau in Miami, Florida, began naming the system the "Great Atlantic hurricane" in their public advisories on September 12 to better convey the life-threatening risks associated with the powerful hurricane.[2] The following day, storm warnings were issued for areas from the United States East Coast from Savannah, Georgia to Cape Hatteras. Small craft in offshore areas further south were advised to remain in port.[9] As Morehead City, North Carolina was forecast to be submerged under several feet of water, the city's entire population was evacuated; other resort locales along the coast of North Carolina were also evacuated. Similarly, the 3000–4000 personnel constituting Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point were evacuated inland; U.S. Army and Navy aircraft were also sent inland.[10]

As the hurricane was passing near the Outer Banks, hurricane warnings were extended as far north as Portland, Maine, and storm warnings were issued as far north as Eastport, Maine.[11] Precautions across New England and Mid-Atlantic states began in earnest once the storm began tracking northwards. Sixty buses were readied in Ocean City, Maryland to evacuate the seaside resort's permanent and tourist residents.[12] The 3,000 residents of Fire Island, one of the barrier islands off of Long Island, were ordered to evacuate the islet. Nearby, the Brooklyn Red Cross Chapter began readying for possible relief work, stocking five mobile canteens with emergency rations.[13] The United States First Naval District were directed to have personnel and rescue craft on standby to respond to emergencies. The Massachusetts State Police began relaying Weather Bureau bulletins to local public services via telecommunications. Personnel on duty were called back to barracks for later deployment in relief operations.[11] The Massachusetts National Guard were ordered to standby and prepare for potential assistance of regional emergency services.[14] Other Massachusetts state agencies were also allocating resources to aid in relief operations.[11]

Impact

North Carolina and Virginia

Passing close to the Outer Banks and Hampton Roads area, strong hurricane-force winds were reported across eastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia. Though the strongest winds recorded peaked at around 90 mph (145 km/h), winds up to 105 mph (170 km/h) were analyzed by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project to have occurred between the two states.[1] The strong winds knocked out telecommunications networks on the Outer Banks, with telephone lines in Manteo, North Carolina and Elizabeth City, North Carolina destroyed by the storm. Small homes in the two cities were also leveled by the winds.[10] Power outages impacted New Bern, North Carolina.[12] At the coast, the hurricane's storm surge pushed 50 ft (15 m) inland along unprotected coastline, destroying hundreds of boats, damaging boardwalks, and depositing debris along the Carolina beaches.[10] Coastal farmland was inundated, with damage to corn and other crops initially estimated at "thousands of dollars."[13]

Jersey Shore

The hurricane was infamous for the amount of damage it caused along the New Jersey coastline. The shore towns on Long Beach Island, as well as Barnegat, Atlantic City, Ocean City, and Cape May all suffered major damage. Long Beach Island, Barnegat Island and Brigantine all lost their causeways to the mainland in the storm effectively cutting them off from the rest of New Jersey. Additionally both islands lost hundreds of homes, in particular the Harvey Cedars section of Long Beach Island where many homes in the town were swept out to sea. In Atlantic City the hurricane's storm surge forced water into the lobbies of many of the resorts famous hotels. The Atlantic City boardwalk suffered major damage along with the Boardwalk Hall Auditorium Organ and the city's famous ocean piers. Both the famed Steel Pier and Heinz Pier were partially destroyed by the hurricane with only the Steel Pier getting rebuilt. Ocean City and Cape May also lost many homes in the storm with Ocean City's boardwalk suffering significant damage. Larry Savadove devotes a whole chapter in his book Great Storms of the Jersey Shore to the hurricane and the imprint and lore it left on the Jersey Shore.

New England

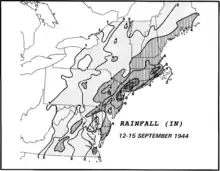

Rain totals of around 7 inches (178 mm) occurred in the Hartford, Connecticut area, and the city of Bridgeport saw the greatest official total at 10.7 inches (272.8 mm). Tobacco and fruit damage in Connecticut totaled to about $2 million (1944 USD), with similar overall damage costs occurring in Rhode Island. More than $5 million (1944 USD) in damage which occurred on Cape Cod can be attributed to lost boats, as well as fallen trees and utility damage.[15] A total of 28 people died throughout New England as a result of the storm. In Bath, Maine, a 10-year-old boy was electrocuted when he came into contact with downed wires. In Augusta, Maine, a 40-year-old woman was run over by a bicyclist who was blinded by heavy rains. 4.34 inches of rain fell during the storm at Bates College. Many tree limbs were downed by high winds during the storm, and in Androscoggin County, Maine, 40% of the apple crop was destroyed.[16]

USS Warrington and other ships

The storm was also responsible for sinking the Navy destroyer USS Warrington approximately 450 miles (720 km) east of Vero Beach, Florida, with a loss of 248 sailors. The hurricane was one of the most powerful to traverse the Eastern Seaboard, reaching Category 4 when it encountered Warrington, and producing hurricane-force winds over a diameter of 600 miles (970 km).[17] The hurricane also produced waves in excess of 70 feet (21 m) in height. The hurricane and the sinking of USS Warrington are documented in the 1996 book The Dragon's Breath - Hurricane At Sea, written by Commander Robert A. Dawes, Jr. (a former Commanding Officer of Warrington), and published by Naval Institute Press.

In addition to Warrington, the Coast Guard cutters CGC Bedloe (WSC-128) and CGC Jackson (WSC-142) both capsized and sank off Cape Hatteras. Seventy-five men managed to escape onto life rafts from Bedloe and Jackson, but only 32 survived the rough seas and subsequent hours of exposure to be rescued two days later.[18] The 136-foot (41 m) minesweeper YMS-409 foundered and sank killing all 33 on board, while the lightship Vineyard Sound (LV-73) was sunk with the loss of all twelve aboard. Finally, the hurricane drove the SS Thomas Tracy aground in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware.

See also

References

- Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; et al. (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- Sumner, H. C. (September 1944). Woolward, Edgar W. (ed.). "The North Atlantic Hurricane Of September 8–14, 1944" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 72 (9): 187–189. Bibcode:1944MWRv...72..187S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1944)072<0187:TNAHOS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "Hurricane Is Brewing In The South Atlantic". The Anniston Star. 82 (224). Anniston, Alabama. United Press. September 10, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 19, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Warning Posted In Bahamas". Statesville Daily Record. 14 (216). Statesville, North Carolina. United Press. September 11, 1944. p. 2. Retrieved June 19, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Moving Toward Miami, But May Turn". Blytheville Courier News. 41 (150). Blytheville, Arkansas. United Press. September 12, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Moves Closer To Coast, May Hit Carolinas". Dunkirk Evening Observer. 194 (62). Dunkirk, New York. United Press. September 13, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Landsea, Christopher W; Dorst, Neal M (June 1, 2014). "Subject: Tropical Cyclone Names: B1) How are tropical cyclones named?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Question. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- "Violent Hurricane Is Headed For Carolinas But It Shows A Slight Tendency To Swerve". The Bee (16, 757). Danville, Virginia. Associated Press. September 13, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "North Carolina Lashed". The Berkshire Evening Eagle. 53 (93). Pittsfield, Massachusetts. United Press. September 14, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved June 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Expected In This Region At 1 To 3 A. M." Fitchburg Sentinel. 72 (110). Fitchburg, Massachusetts. Associated Press. September 14, 1944. pp. 1, 12. Retrieved June 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Killer Hurricane Lashes Carolina Amid Heavy Rain". The Odgen Standard-Examiner. 75 (85). Odgen City, Utah. United Press. September 14, 1944. pp. 1–2. Retrieved June 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Long Island Prepares For Hurricane". Brooklyn Eagle. 103 (252). Brooklyn, New York. Brooklyn Eagle. September 14, 1944. pp. 1, 5. Retrieved June 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "All City Services Alerted At Noon To Meet Disaster". Fitchburg Sentinel. 72 (110). Fitchburg, Massachusetts. Fitchburg Sentinel. September 14, 1944. pp. 1, 12. Retrieved June 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1944- Great Atlantic Hurricane". Hurricanes: Science and Society. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- Cotterly, Wayne. "Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944". Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- Rothovius, Andrew (September 13, 1984). "The great Atlantic hurricane". The Peterborough Transcript. pp. 4, 6.

- Thiesen, William H. (June 11, 2018). "The Long Blue Line: Jackson's battle with the rogue waves of '44". U.S. Coast Guard. Retrieved October 19, 2020.