1796 United States presidential election

The 1796 United States presidential election was the third quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Friday, November 4 to Wednesday, December 7, 1796. It was the first contested American presidential election, the first presidential election in which political parties played a dominant role, and the only presidential election in which a president and vice president were elected from opposing tickets. Incumbent Vice President John Adams of the Federalist Party defeated former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

139 members of the Electoral College at least 70 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 20.1%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

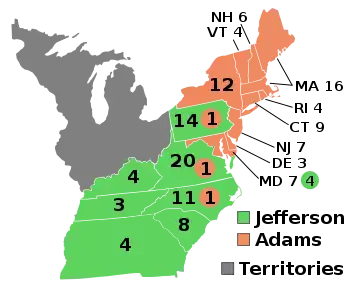

Presidential election results map. Green denotes states won by Jefferson and burnt orange denotes states won by Adams. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes cast by each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With incumbent President George Washington having refused a third term in office, the 1796 election became the first U.S. presidential election in which political parties competed for the presidency. The Federalists coalesced behind Adams and the Democratic-Republicans supported Jefferson, but each party ran multiple candidates. Under the electoral rules in place prior to the 1804 ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, the members of the Electoral College each cast two votes, with no distinction made between electoral votes for president and electoral votes for vice president. The individual with the majority of the total votes cast became president, and the runner-up became vice president. In case of a first place tie between candidates who received votes from a majority of electors, or should no individual win a majority, the House of Representatives would hold a contingent election. Also, if there were a tie for second place, the vice presidency, the Senate would hold a contingent election to break the tie.

The campaign was a bitter one, with Federalists attempting to identify the Democratic-Republicans with the violence of the French Revolution[2] and the Democratic-Republicans accusing the Federalists of favoring monarchism and aristocracy. Republicans sought to associate Adams with the policies developed by fellow Federalist Alexander Hamilton during the Washington administration, which they declaimed were too much in favor of Great Britain and a centralized national government. In foreign policy, Republicans denounced the Federalists over the Jay Treaty, which had established a temporary peace with Great Britain. Federalists attacked Jefferson's moral character, alleging he was an atheist and that he had been a coward during the American Revolutionary War. Adams supporters also accused Jefferson of being too pro-France; the accusation was underscored when the French ambassador embarrassed the Republicans by publicly backing Jefferson and attacking the Federalists right before the election.[3] Despite the hostility between their respective camps, neither Adams nor Jefferson actively campaigned for the presidency.[4][3]

Adams was elected president with 71 electoral votes, one more than was needed for a majority. Adams won by sweeping the electoral votes of New England and winning votes from several other swing states, especially the states of the Mid-Atlantic region. Jefferson received 68 electoral votes and was elected vice president. Former Governor Thomas Pinckney of South Carolina, a Federalist, finished with 59 electoral votes, while Senator Aaron Burr, a Democratic-Republican from New York, won 30 electoral votes. The remaining 48 electoral votes were dispersed among nine other candidates. Reflecting the evolving nature of both parties, several electors cast one vote for a Federalist candidate and one vote for a Democratic-Republican candidate. The election marked the formation of the First Party System, and established a rivalry between Federalist New England and Democratic-Republican South, with the middle states holding the balance of power (New York and Maryland were the crucial swing states, and between them only voted for a loser once between 1789 and 1820).[5]

Candidates

With the retirement of Washington after two terms, both parties sought the presidency for the first time. Before the ratification of the 12th Amendment in 1804, each elector was to vote for two persons, but was not able to indicate which vote was for president and which was for vice president. Instead, the recipient of the most electoral votes would become president and the runner-up vice president. As a result, both parties ran multiple candidates for president, in hopes of keeping one of their opponents from being the runner-up. These candidates were the equivalent of modern-day running mates, but under the law they were all candidates for president. Thus, both Adams and Jefferson were technically opposed by several members of their own parties. The plan was for one of the electors to cast a vote for the main party nominee (Adams or Jefferson) and a candidate besides the primary running mate, thus ensuring that the main nominee would have one more vote than his running mate.

Federalist candidates

The Federalists' nominee was John Adams of Massachusetts, the incumbent vice president and a leading voice during the Revolutionary period. Most Federalist leaders viewed Adams, who had twice been elected vice president, as the natural heir to Washington. Adams's main running mate was Thomas Pinckney, a former governor of South Carolina who had negotiated the Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain. Pinckney agreed to run after the first choice of many party leaders, former Governor Patrick Henry of Virginia, declined to enter the race. Alexander Hamilton, who competed with Adams for leadership of the party, worked behind the scenes to elect Pinckney over Adams by convincing Jefferson electors from South Carolina to cast their second votes for Pinckney. Hamilton did prefer Adams to Jefferson, and he urged Federalist electors to cast their votes for Adams and Pinckney.[6]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Samuel Johnston,

Samuel Johnston,

Former U.S. Senator from North Carolina

Democratic-Republican candidates

The Democratic-Republicans united behind former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who had co-founded the party with James Madison and others in opposition to the policies of Hamilton. Congressional Democratic-Republicans sought to also unite behind one vice presidential nominee. With Jefferson's popularity strongest in the South, many party leaders wanted a Northern candidate to serve as Jefferson's running mate. Popular choices included Senator Pierce Butler of South Carolina and three New Yorkers: Senator Aaron Burr, Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, and former Governor George Clinton, to be the party's 1796 candidate for vice president. A group of Democratic-Republican leaders met in June 1796 and agreed to support Jefferson for president and Burr for vice president.[6][7]

Aaron Burr,

Aaron Burr,

U.S. Senator from New York

Results

Tennessee was admitted into the United States after the 1792 election, increasing the Electoral College to 138 electors.

Under the system in place prior to the 1804 ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, electors were to cast votes for two persons for president; the runner-up in the presidential race was elected vice-president. If no candidate won votes from a majority of the Electoral College, the House of Representatives would hold a contingent election to select the winner. Each party intended to manipulate the results by having some of their electors cast one vote for the intended presidential candidate and one vote for somebody besides the intended vice-presidential candidate, leaving their vice-presidential candidate a few votes shy of their presidential candidate. However, all electoral votes were cast on the same day, and communications between states were extremely slow at that time, making it very difficult to coordinate which electors were to manipulate their vote for vice-president. Additionally, there were rumors that southern electors pledged to Jefferson were coerced by Hamilton to give their second vote to Pinckney in hope of electing him president instead of Adams.

Campaigning centered in the swing states of New York and Pennsylvania.[8] Adams and Jefferson won a combined 139 electoral votes from the 138 members of the Electoral College. The Federalists swept every state north of the Mason-Dixon line, with the exception of Pennsylvania. However, one Pennsylvania elector voted for Adams. The Democratic-Republicans won the votes of most Southern electors, but the electors of Maryland and Delaware gave a majority of their votes to Federalist candidates, while North Carolina and Virginia both gave Adams one electoral vote.

Nationwide, most electors voted for Adams and a second Federalist or for Jefferson and a second Democratic-Republican, but there were several exceptions to this rule. One elector in Maryland voted for both Adams and Jefferson, and two electors cast votes for Washington, who had not campaigned and was not formally affiliated with either party. Pinckney won the second votes from a majority of the electors who voted for Adams, but 21 electors from New England and Maryland cast their second votes for other candidates, including Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth. Those who voted for Jefferson were significantly less united in their second choice, though Burr won a plurality of the Jefferson electors. All eight electors in Pinckney's home state of South Carolina, as well as at least one elector in Pennsylvania, cast their ballots for Jefferson and Pinckney. In North Carolina, Jefferson won 11 votes, but the remaining 13 votes were spread among six different candidates from both parties. In Virginia, most electors voted for Jefferson and Governor Samuel Adams of Massachusetts.[9]

The end result was that Adams received 71 electoral votes, one more than required to be elected president. If any two of the three Adams electors in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina had voted with the rest of their states, it would have flipped the election. Jefferson received 68 votes, nine more than Pinckney, and was elected vice president. Burr finished in a distant fourth place with 30 votes. Nine other individuals received the remaining 48 electoral votes. If Pinckney had won the second votes of all of the New England electors who voted for Adams, he would have been elected president over Adams and Jefferson.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a), (b), (c) | Electoral vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| John Adams | Federalist | Massachusetts | 35,726 | 53.4% | 71 |

| Thomas Jefferson | Democratic-Republican | Virginia | 31,115 | 46.6% | 68 |

| Thomas Pinckney | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 59 |

| Aaron Burr | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 30 |

| Samuel Adams | Democratic-Republican | Massachusetts | — | — | 15 |

| Oliver Ellsworth | Federalist | Connecticut | — | — | 11 |

| George Clinton | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 7 |

| John Jay | Federalist | New York | — | — | 5 |

| James Iredell | Federalist | North Carolina | — | — | 3 |

| George Washington | Independent | Virginia | — | — | 2 |

| John Henry | Federalist[10] | Maryland | — | — | 2 |

| Samuel Johnston | Federalist | North Carolina | — | — | 2 |

| Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 66,841 | 100.0% | 276 | ||

| Needed to win | 70 | ||||

Source (Popular Vote): U.S. President National Vote. Our Campaigns. (February 11, 2006).

Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825[11]

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

(a) Votes for Federalist electors have been assigned to John Adams and votes for Democratic-Republican electors have been assigned to Thomas Jefferson.

(b) Only 9 of the 16 states used any form of popular vote.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

Electoral votes by state

| State | Candidates | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | E | J. Adams | Jefferson | T. Pinckney | Burr | S. Adams | Ellsworth | Clinton | Jay | Iredell | Johnston | Washington | Henry | C. Pinckney |

| Connecticut | 9 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Delaware | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Georgia | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kentucky | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Maryland | 10 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Massachusetts | 16 | 16 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Hampshire | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Jersey | 7 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New York | 12 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| North Carolina | 12 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pennsylvania | 15 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South Carolina | 8 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tennessee | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vermont | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Virginia | 21 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 138 | 71 | 68 | 59 | 30 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Source: Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections[12]

Popular vote by state

While popular vote data is available for some states, presidential elections were vastly different in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Instead of the name of the presidential candidates, voters would see the name of an elector. Confusion over who the elector would vote for was common. Several states also elected a statewide slate of electors (for example, since Thomas Jefferson won the popular vote in Georgia, the slate of four Jefferson electors was chosen) but because of the archaic voting system, votes were tallied by elector, not candidate. The popular vote totals used are the elector from each party with the highest total of votes. The vote totals of Kentucky, North Carolina, and Tennessee appear to be lost.

| State | Adams | Jefferson | Margin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Georgia | 249 | 3.56% | 6,200 | 96.44% | 5,951 | 92.88% |

| Kentucky | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Maryland | 7,029 | 51.99% | 6,490 | 48.01% | 539 | 3.98% |

| Massachusetts | 5,247 | 100.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 5,247 | 100.00% |

| New Hampshire | 3,719 | 84.52% | 681 | 15.48% | 3,038 | 69.04% |

| North Carolina | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Pennsylvania | 12,185 | 49.75% | 12,306 | 50.25% | 121 | 0.5% |

| Tennessee | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Virginia | 1,722 | 31.64% | 3,721 | 68.36% | 1,999 | 36.72% |

Source: A New Nation Votes[13]

Close states

States where the margin of victory was under 1% (15 electoral votes):

- Pennsylvania, 0.5%

States where the margin of victory was under 5% (11 electoral votes):

- Maryland, 3.98%

Consequences

The following four years would be the only time (as of 2021) that the president and vice-president were from different parties. While John Quincy Adams and John C. Calhoun would later be elected president and vice-president as political opponents, they were both Democratic-Republican party candidates, and while Andrew Johnson, Abraham Lincoln's second vice-president, was a Democrat, Lincoln ran on a combined National Union Party ticket in 1864, not as a strict Republican.

Jefferson would leverage his position as vice-president to attack President Adams's policies, and this would help him reach the White House in the following election.

This election would provide part of the impetus for the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1804.

On January 6, 1797, Representative William L. Smith of South Carolina presented a resolution on the floor of the House of Representatives for an amendment to the Constitution by which the presidential electors would designate which candidate would be president and which would be vice-president.[14] However, no action was taken on his proposal, setting the stage for the deadlocked election of 1800.

Electoral college selection

The Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, provided that the state legislatures should decide the manner in which their Electors were chosen. Different state legislatures chose different methods:[15]

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| Each Elector appointed by the state legislature | Connecticut Delaware New Jersey New York Rhode Island South Carolina Vermont |

| State is divided into electoral districts, with one Elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | Kentucky Maryland North Carolina Virginia |

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide | Georgia Pennsylvania |

|

Massachusetts |

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide; however, if no candidate wins majority, the state legislature appoints Elector from top two candidates | New Hampshire |

|

Tennessee |

See also

References

- "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- Presidential Election of 1796, retrieved on November 5, 2009.

- "John Adams: Campaigns and Elections—Miller Center". millercenter.org. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- "Inside America's first dirty presidential campaign, 1796 style". Constitution Daily. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- Jeffrey L. Pasley, The First Presidential Contest: 1796 and the Founding of American Democracy (2013)

- Sharp, James Roger (1993). American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. Yale University Press. pp. 146–148.

- Patrick, John J.; Pious, Richard M.; Ritchie, Donald A. (2001). The Oxford Guide to the United States Government. Oxford University Press. p. 93.

- Waldstreicher, David (2013). My library My History Books on Google Play A Companion to John Adams and John Quincy Adams. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 150–151.

- "1796 President of the United States, Electoral College". A New Nation Votes. American Antiquarian Society. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- "MARYLAND'S ELECTORAL VOTE FOR U.S. PRESIDENT, 1789-2016". Maryland Manual On-line. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- http://elections.lib.tufts.edu/catalog?commit=Limit&f%5Belection_type_sim%5D%5B%5D=General&f%5Boffice_id_ssim%5D%5B%5D=ON056&page=2&q=1820&range%5Bdate_sim%5D%5Bbegin%5D=1820&range%5Bdate_sim%5D%5Bend%5D=1820&search_field=all_fields&utf8=%E2%9C%93

- "1796 Presidential Electoral Vote Count". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Dave Leip. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- United States Congress (1797). Annals of Congress. 4th Congress, 2nd Session. p. 1824. Retrieved June 26, 2006.

- "The Electoral Count for the Presidential Election of 1789". The Papers of George Washington. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2005.

- Web references

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved March 20, 2005.

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825

Primary sources

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr. ed. The Making of the American Party System 1789 to 1809 (1965), short excerpts from primary sources

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr., ed. Circular Letters of Congressmen to Their Constituents 1789-1829 (1978), 3 vol; political reports sent by Congressmen to local newspapers

Further reading

- Encyclopedia of the New American Nation, 1754–1829 ed. by Paul Finkelman (2005), 1600 pp.

- The North Carolina Electoral Vote: The People and the Process Behind the Vote. Raleigh, North Carolina: North Carolina Secretary of State. 1988.

- Banning, Lance. The Jeffersonian Persuasion: Evolution of a Party Ideology (1978)

- Chambers, William Nisbet, ed. The First Party System (1972)

- Chambers, William Nisbet. Political Parties in a New Nation: The American Experience, 1776–1809 (1963)

- Charles, Joseph. The Origins of the American Party System (1956), reprints articles in William and Mary Quarterly

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr. Jeffersonian Republicans: The Formation of Party Organization: 1789–1801 (1957)

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr., "John Beckley: An Early American Party Manager," William and Mary Quarterly, 13 (Jan. 1956), 40-52, in JSTOR

- Dawson, Matthew Q. Partisanship and the Birth of America's Second Party, 1796-1800: Stop the Wheels of Government. Greenwood, (2000) online version

- DeConde, Alexander. "Washington's Farewell, the French Alliance, and the Election of 1796," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 43, No. 4 (Mar. 1957), pp. 641–658 in JSTOR

- Dinkin, Robert J. Campaigning in America: A History of Election Practices. (Greenwood 1989) online version

- Elkins, Stanley and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism (1995) online version, the standard highly detailed political history of 1790s

- Freeman, Joanne. "The Presidential Election of 1796," in Richard Alan Ryerson, ed. John Adams and the Founding of the Republic (2001).

- Miller, John C. The Federalist Era: 1789-1801 (1960).

- Pasley, Jeffrey L. The First Presidential Contest: 1796 and the Founding of American Democracy. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier, ed. History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–1984 (Vol 1) (1986), essay and primary sources on 1796

- Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (2009)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1796. |

- United States presidential election of 1796 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Presidential Election of 1796: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Election of 1796 in Counting the Votes Archived January 13, 2015, at the Wayback Machine