Âu Lạc

Âu Lạc (Hán tự: 甌貉/ 甌駱/ 甌雒; Chinese pinyin: ōu luò; Wade–Giles: Wu1-lo4) was an ancient Yue kingdom that covered parts of modern-day Guangxi and northern Vietnam to Hoành Sơn Range.[2] Founded in 257 BCE, it was a merger of the former states of Nam Cương (Âu Việt) and Văn Lang (Lạc Việt)[3] but succumbed to the state of Nanyue in 180 BCE, which, itself was finally conquered by the Han dynasty.[4][5] Its capital was in Cổ Loa, roughly 17 kilometers north of present-day Hanoi, in the upper plain north of the Hong River.[6]

Âu Lạc 甌貉/ 甌駱/ 甌雒 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 257 BCE–180 BCE | |||||||||||

Âu Lạc locates in the southern-most of Baiyue | |||||||||||

| Capital | Cổ Loa | ||||||||||

| Religion | possibly Shamanism, Animism and Polytheism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 257 BCE – 180 BCE | An Dương Vương (first and last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||||

• Established | 257 BCE | ||||||||||

| 180 BCE | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | China Vietnam | ||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Vietnam |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

History

Foundation

Prior to the Chinese domination in the region, northern and north-central Vietnam had been ruled by Lạc kings (Hùng kings) who were served by Lạc hầu and Lạc tướng.[7] In approximately 257 BCE, they were annexed by the Âu Việt state of Nam Cương. The leader of the Âu Việt, Thục Phán, overthrew the last Hùng kings, and unified the two kingdoms under the name of Âu Lạc, proclaiming himself King An Dương (An Dương Vương).[8]

His antecedents are "cloudy" since the only information provided by written accounts is that his family name was Thục, and his personal name was Phán, which appears to associate him with the ancient state of Shu in what is now Sichuan, conquered by Qin dynasty in 316 BCE.[8][9] This was also the traditional view of Chinese and Vietnamese historians. Many chronicles including Records of the Outer Territories of the Jiao province,[10] Đại Việt sử lược, Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư stated that he was a son of King Thục, but they were unable to describe precisely his origin. Later historians had a more nuanced view. In Khâm định Việt sử Thông giám cương mục, the writters expressed doubts about King An Dương Vương's origin, claiming it was impossible for a Shu prince to cross thousands of miles, through forests, many states to invade Văn Lang.[11] In 1963, an oral tradition of Tày people in Cao Bằng titled "Cẩu chủa cheng vùa" was recorded. [8][12] According to this account, at the end of Hồng Bàng dynasty, there was a kingdom called Nam Cương (lit. “southern border), comprising portions of modern-day Cao Bằng and Guangxi.[8] It consisted of 10 regions, in which the King resided in the central one (present-day Cao Bằng Province).The other nine regions were under the control of nine lords.[13] While King An Dương Vương's father (Thục Chế 蜀制) died, he was still a child; yet, his intelligence enabled him to retain the throne and all the lords surrendered. Nam Cương became more and more powerful while Văn Lang became weak.[8][12] Subsequently, he invaded Văn Lang and founded the state of Âu Lạc. The tale is supported by many vestiges, relics and place names in Cao Bằng Province. The assumption about his origin as local habitant has also been reflected in various fairy tales, registers, worships and folk memories. According to historian Đào Duy Anh in Đất nước Việt Nam qua các đời: nghiên cứu địa lý học lịch sử Việt Nam, the southern part of Zuo River, the drainage basin of You River and the upstream area of Lô River, Gâm River, and Cầu River are inhabited by Âu Việt tribes with the supreme leader Thục Phán.[14]

According to the Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian, Âu Lạc was referred as the "Western Ou" (Vietnamese: Tây Âu) and "Luo" (Vietnamese: Lạc) and they were lumped into the category of Baiyue, an exonym used by the Sinitic peoples to the north.[15][16][17]

Construction of Cổ Loa Citadel

Kinh An Dương established the capital of Âu Lạc in Tây Vu, where a fortified citadel is constructed, known to history as Cổ Loa.[18] It was the first political center of the Vietnamese civilization pre-Sinitic era,[19] with an outer embankment covering 600 hectares.[20] This name was derived from the Sino-Vietnamese 古螺, meaning "old spiral", reflecting its multi-layered structure of earthworks, moats and ditches. However, according to Dr. Lê Chí Quế, Cổ Loa is spelled of Old Vietnamese word k'la (Chinese: 雞) means chicken. It corresponds to the legend of the white chicken that stalled the construction of the citadel. Near Cổ Loa commune there is an old site that was Chicken village (Vietnamese: Thôn Kẻ La / Xóm Gà). This site coincides to the legend that belonged to one tribe's totem.

Given its relatively large size, Cổ Loa maintained its dominant presence in the northern floodplain of the Red River Delta and would have required a large amount of labour and resources to construct.[21] The events associated with the building of Cổ Loa have been remembered in the legend of the golden turtle. According to this legend, when the citadel was being built, all the work done during the day was mysteriously undone during the night by a group of spirits seeking to gain revenge for the son of the previous king.[22] The local spirits were led by a thousand-year-old white chicken perched on nearby Mount Tam Đảo. The king made a sacrifice to the gods and a golden turtle appeared, subdued the white chicken, and protected King An Dương until the citadel's compleition. When he departed, he gave one of his claws to be used as the trigger of the king’s crossbow, with the assurance that with it he could destroy any foe.

King An Dương commissioned Cao Lỗ (or Cao Thông) to construct a crossbow and christened it "Saintly Crossbow of the Supernaturally Luminous Golden Claw" (nỏ thần), which one shot could killed 300 men.[7][22] According to historian K. W. Taylor, the crossbow, along with the word for it, seems to have been introduced into China from Austroasiatic peoples in the south during the third or fourth century BCE.[22] This weapon quickly became part of the Chinese arsenal; its trigger mechanism was capable of withstanding high pressure and of releasing an arrow with more force than any other type of bow. Two bronze trigger mechanisms have been excavated in Vietnam; most mechanisms were probably made of bamboo. The turtle claw used as a trigger mechanism indicates the military nature of King An Dương’s conquest and suggests that his rule was based on force or the threat of force.[22]

War with Nanyue and collapse

In 204 BCE, in Panyu (now Guangzhou), Zhao Tuo, a native of Zhending,[23][24] in the state of Zhao (modern-day Hebei), established the kingdom of Nanyue.[25] Having mobilized his armies for war with the Han dynasty, Zhao Tuo found the conquest of Âu Lạc both "tempting and feasible".[26]

The details of the campaign are not authentically recorded. Zhao Tuo's early setbacks and eventual victory against King An Dương were mentioned in Records of the Outer Territories of the Jiao province.[10] Records of the Grand Historian mentioned neither King An Duong nor Zhao Tuo's military conquest of Âu Lạc; just that after Empress Lü's death (180 BCE), Zhao Tuo used his own troops to menace and used wealth to bribe the Minyue, the Western Ou, and the Luo into submission.[27] However, the compaign inspired a legend whose theme is the transfer of the turtle claw-triggered crossbow from King An Duong to Zhao Tuo. According to this legend, ownership of the crossbow conferred the political power:“He who is able to hold this crossbow rules the realm; he who is not able to hold this crossbow will perish.”[28][29][30]

Unsuccessful on the battlefield against the supernatural crossbow, Zhao Tuo asked for a truce and sent his son Zhong Shi, to submit to King An Dương to serve him.[31][29] There, he and King An Duong’s daughter, Mỵ Châu, fell in love and were married.[29][32] A vestige of the matrilocal organization demanded that the husband came to live in the residence of his wife’s family.[33] As a result, they resided at An Duong’s court until Zhong Shi managed to lay his hands upon the magic crossbow that was the source of King An Duong’s power.[33] Meanwhile, King An Duong treated Cao Lỗ disrespectfully, and he abandoned him.[34]

Zhong Shi had Mỵ Châu show him her father's sacred crossbow, at with point he secretly changed its trigger, thus neutralizing its special powers.[32] He stole the turtle claw, rendering the crossbow useless, then returned to his father, who thereupon launched new attack on Âu Lạc and this time defeated King An Dương.[33] History records that, in his defeat, the King jumped into the ocean to commit suicide. In some versions, he was told by the turtle about his daughter's betrayal and killed his daughter for her treachery before killing himself. A legend, however, discloses that a golden turtle emerged from the water and guided him into the watery realm.[29]

According to K. W. Taylor, the archaeological findings of Cổ Loa uncovers an adaptation of engineering practices from the Warring States to the local terrain and a range of weapons analogous to contemporary armies in China, suggesting that King An Dương’s magic crossbow may have been some type of “new model army” trained and led by Cao Thông, which was no longer effective without his leadership.[35]

Zhao Tuo subsequently incorporated the regions into his Nanyue domain, but left the indigenous chiefs in control of the population with the royal court in Cổ Loa.[36][37][38] For the first time, the region formed part of a polity headed by a Chinese ruler.[39] He posted two legates to supervise the Âu Lạc lords, one in the Red River Delta, which was named Giao Chỉ, and one in the Mã and Cả River, which was named Cửu Chân.[2][40] Some records suggest that he also invested a king at Cổ Loa who continued to preside over the Âu Lạc lords. The legates established commercial outposts accessible by sea.[40]

In 111 BC, the Han dynasty conquered Nanyue and ruled it for the next several hundred years.[41][42] Local Lạc lords, just as under Nanyue, bent with the northern wind to preserve their autonomy, bestowed imperial “seals and ribbons” as symbols of their status in return for what they viewed as “tribute to a suzerain” but which Han officials viewed as taxes.[40] It was not until the fourth decade of the first century CE that more direct rule and greater efforts at Sinicization were imposed by the Han dynasty.[43][44] K. W. Taylor believed:"Local society and the people who ruled it do not appear to have experienced any major disruption as Han officials garrisoned headquarters at a few strategic locations and began to attract immigrants from the north. As years went by, however, contradictions between imperial policy and local practice grew ever more apparent and eventually led to the violence of the 40s CE."[45] The territories of the Lạc lords were revoked and ruled directly, as provinces of the Han dynasty. In his words:“The Vietnamese were deprived of their traditional ruling class, and the struggle for cultural survival became closely identified with the more basic problem of physical survival under an exploitative, alien regime.”[46]

Government and organization

The local organization of society and politics apparently remained fundamentally unchanged compared to Văn Lang.[40] It was a relatively primitive form of a sovereign state with no definitive political institutions. Control over the land and the exercise of power were highly decentralized.[47] The state did not have a written law, and the social relations were regulated by customary law.

According to Joseph Buttinger, in such a society, the principal human relationship is one of vassalage, or dependence of the lower groups on the next higher of smaller size, reaching through several stages from the great numbers at the base to the head of the feudal order, the King. Dependence is rooted in the power of the higher ranks to dispose of the available land, a power always formalized as right, with a claim to some supernatural sanction. Among the early Vietnamese, all land, although it belongs theoretically to the people, was in the trust of the King.[48]

Similar to Văn Lang, the country was headed by the King, who was assisted by advisors called the Lạc hầu.[7] The country was composed of various regions, each ruled by a Lạc tướng.[7] They then subdivided their domains among the lower nobility, whose members were the chiefs of villages or of groups of villages. Their charges and privileges, like those of the higher nobles, were hereditary; they were the civil, military, and religious authority in one. As such, they administered justice, led in war, presided over local festivals and religious ceremonies.[48]

Language

K. W. Taylor conjectured that much of the lowland population spoke what linguists call Proto-Viet-Muong related to the Mon-Khmer language family that apparently expanded northward from the Cả River delta in modern Nghệ An and Hà Tĩnh Provinces. The geographical connection with other Mon-Khmer languages appears to have been via the Mụ Giạ Pass from the middle Mekong Delta to the Cả River delta. Another plausible conjecture is that the aristocracy that ruled these people, called Lạc in Han texts, came from the mountains north and west of the Red River Delta and spoke an ancient language related to modern Khmu, another Mon-Khmer language now spoken in the mountains of northern Vietnam and Laos. On the other hand, the Âu conquerers who arrived from the northern mountains with King An Duong might be imagined to have spoken a language related to the Tai-Kadai language family that includes modern Lao and Thai.[49]

Ferlus (2009) showed that the inventions of pestle, oar and a pan to cook sticky rice, which is the main characteristic of the Đông Sơn culture, correspond to the creation of new lexicons for these inventions in Northern Vietic (Việt–Mường) and Central Vietic (Cuoi-Toum). The new vocabularies of these inventions were proven to be derivatives from original verbs rather than borrowed lexical items. The current distribution of Northern Vietic also correspond to the area of Đông Sơn culture. Thus, Ferlus concludes that the Northern Vietic (Việt–Mường) speakers are the "most direct heirs" of the Dongsonians, who have resided in Southern part of Red river delta and North Central Vietnam since the 1st millennium BCE.[50]

Culture and society

In the highlands, people practiced slash-and-burn agriculture while in the plains, where water was abundant, irrigation systems were developed. They knew an early technique of irrigation: the use of the ocean tides that affected the water levels far into the flat delta.[51][52]

The Vietnamese continued to raise fowl, oxen, buffalo, pigs, dogs, turtles, and frogs. The presence of bronze hooks and baked clay sinkers prove the existence of line fishing. Boats with rudders were carved out of forest trees. They were capable of carrying dozens of passengers. Kilns and potting wheels were used to produce large quantities of jewelry, pans, plates, and pots, some of which were painted. They were generally mass produced, with some specialization and division of labor. Agriculture produced enough of a surplus to feed the labor forces who transferred from the rice fields to the industrial shops. Bartering developed as a result of high productivity.[53]

Lạc lords were hereditary aristocrats in something like a feudal system. The status of Lạc lords passed through the family line of one’s mother and tribute was obtained from communities of agriculturalists who practiced group responsibility. In Lạc society, access to land was based on communal usage rather than individual ownership and women possessed inheritance rights. While in Chinese society men inherited wealth through their fathers, in Lạc society both men and women inherited wealth through their mothers.[54]

According to Linh Nam chich quai, the Duke of Zhou said to the envoys, “Why do you people from Jiaozhi have short hair, tattoo your bodies, and go bareheaded and barefooted?” The author of Linh Nam chich quai expressed cultural pride through the mouths of envoys to the Zhou court: “Short hair is for convenience when traveling through the mountains and forests. We tattoo our bodies to look like dragons, so when we travel through the water the flood dragon will not dare to attack us. We go barefoot for convenience when climbing trees. We engage in slash and burn agriculture [and leave our heads bare] to beat the heat. We chew betel to get rid of filth, and therefore our teeth become black.”[55]

Ancient Han Chinese had described the people of Âu Lạc as barbaric,[56] comparing their language to animal shrieking and had regarded them as lacking morals and modesty. However, according to Olivia Milburn, the egalitarian nature of their society, along with the comparatively high status of women, the practice of getting married without a matchmaker and indeed consulting the wishes of the couple concerned, all now seem enlightened rather than barbaric.[57]

A Chinese text dating from the 220s BCE reporting "unorthodox customs" of the Yue in a part of the Lạc Việt region states:“To crop the hair, decorate the body, rub pigment into arms and fasten garments on the left side is the way of the Bakviet. In the country of Tai-wu (Vietnamese: Tây Vu) the habit is to blacken teeth, scar cheeks and wear caps of sheat [catfish] skin stitched crudely with an awl.”[58]

According to Hou Hanshu, the whole territory of the Âu Lạc people is covered with dense forests, ponds and lakes. There are a lot of wild animals like elephants, rhinoceros and tigers. The natives earn their living by hunting and fishing. They eat the meat of boa constrictors, snakes and wild animals which they kill with bows propelling bone-headed arrows....In fighting, they use bows propelling poisoned arrows. The process of making poison for arrows is a secret which they swear never to disclose to anyone. They know how to cast copper implements and pointed arrowheads. The natives tattoo themselves, wear chignon and turbans. They chew betel nuts and blacken their teeth.[59]

Chinese writers noted the Yue preoccupation with aquatic life. One text, the Huainanzi, stated in 135 BCE that in Nanyue, which then included the Red River Delta, “people carry out few occupations on land and many on water.” The inhabitants even cut their hair and “tattoo their bodies in order to resemble the scaly-skinned aquatic animals.”[60]

Lạc Việt people organized themselves along less strict, nonnuclear lines, giving authority to women as well as men. They formed matrilocal clans: couples after marriage would often go to live with the wife’s family. This matrilocal custom kept sisters together and gave married women key roles in social communication, and some were regarded as at least the equals of men. [61] Unmarried couples often lived together. This relatively open family structure contrasted with most of Chinese society, which was based increasingly though not solely on Confucian notions of the patriarchal family, in particular “filial piety,” which also provided a model for imperial government.[62] In addition, they also practiced levirate.[63][64] This meant that childless widows had a right to bear children with men from their deceased husbands’ families in order to obtain heirs. This practice ostensibly provided an heir for the mother, although some patriarchal societies used it to provide an heir for the deceased father.[54] If the levirate was an innovation designed to keep land holdings in the same male family, it also reflected an earlier tradition of female authority and protection of widows’ interests.[63] Linguistic vestiges of female status corroborate this view. Huỳnh Sanh Thông identified no fewer than thirty-two Vietnamese words for “mother” or “woman,” including seven archaic and twelve modern terms for “mother.” These also carry important other meanings, involving fertility, water, agriculture, and bronze drums. The words for water (nác/nước) and “country” (nước) derive from one of the archaic Vietnamese terms for woman (nàng), while another, nương, is also used to describe an upland field or swidden. Of two Vietnamese words for “witch, female medium,” one (bóng) also means a type of drum. The other (đồng), a homonym for both “bronze” and “a field in the country,” combines with an archaic term for “mother” (áng) to form đồng áng (“ricefields; the countryside”). All this suggests a possible Earth Mother cult and rituals associating water and fertility with bronze drums and female shamans.[65]

Women also remained prominent in indigenous religious rites, including water rituals. Local worship of the Chư vị, or Spirits of the Three Worlds—Heaven, Earth, and Water—was still popular. Most of the priests or spirit mediums involved in this were women.[66]

Archaeological findings

The site consists of two outer sets of ramparts and a citadel on the inside, of rectangular shape. The moats consist of a series of streams, including the Hoang Giang River and a network of lakes that provided Cổ Loa with protection and navigation.[21]

The outer rampart comprises a perimeter of 8 km and is lined with guard towers. The ramparts still stand up to 12 m high and are 25 m in width at their base. Besides, part of the inner rampart was cut through for the purpose of archaeological investigation, which was dated from 400-350 BCE. And it was suggested that this rampart was constructed by a local and indigenous society prior to the colonization of Han dynasty.[67] The stamped earth technique or hang-tu method associated with ancient China may have been used in Cổ Loa, but studies of the defensive works are still in a preliminary stage. Also, archaeologists have estimated that over two million cubic metres of material were moved in order to construct the entire fortress, including moats that were fed by the Hoang River.[21]

Then in 2007 - 2008 another excavation took place that excavated the middle wall of Cổ Loa citadel. The excavation cut through the entire width of the rampart. The stratification showed multiple layers of construction deposits: three periods and five major phases of construction.[67]

Excavations made by archaeologists have revealed Dong Son style pottery that had stratified over time under the walls, while a drum was found by chance by Nguyen Giang Hai and Nguyen Van Hung. The drum included a hoard of bronze objects. The rarity of such objects in Southeast Asia and the range found at Co Loa is believed to possibly be unique.[21] The drum itself is one of the largest Bronze Age drums to have been recovered from the Red River Delta, standing 57 cm high and boasting a tympanum with a diameter of 73.6 cm. The drum itself weighs 72 kg and contains around 200 pieces of bronze, including 20 kg of scrap pieces from a range of artefacts. These include socketed hoes and ploughshares, socketed axes, and spearheads.[21]

The artifacts are numerically dominated by the ploughshares, of which there are 96. Six hoes and a chisel were in the set. There were 32 socketed axes of various shapes, including a boat shaped axehead. This was almost a replica to a clay mound found in the grave of the bronze metalworker at Lang Ca. Sixteen spearheads, a dagger and eight arrowheads were also found. One spearhead generated special interest because it was bimetallic, with an iron blade fitting into a bronze socket.[21]

Excavations in 2004 and 2005 revealed kilns, bricks, stylized ceramic roof tiles, and stone moulds for casting bronze arrowheads, indicating that bronzes were produced locally. Cổ Loa artifacts may be correlated with the presence of an elite which controlled indigenous resources and centralized production of objects, such as bronzes, a sizable proportion of which comprised weapons indicative of increasing conflict in the region and perhaps between Co Loa and the Chinese.[19]

Gallery

.png.webp)

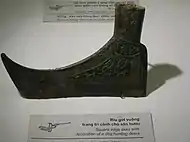

A square-edge axe with decoration of dog hunting deer, Dong Son culture, 500 BCE-0.

A square-edge axe with decoration of dog hunting deer, Dong Son culture, 500 BCE-0. Pieces of Đông Sơn bronze lamellar armor, 3rd to 1st century BC

Pieces of Đông Sơn bronze lamellar armor, 3rd to 1st century BC Bronze daggers, Dong Son Culture, 500 BCE - 0.

Bronze daggers, Dong Son Culture, 500 BCE - 0. The leg ring made from bronze dating from 500 BC-0.

The leg ring made from bronze dating from 500 BC-0. Water buffalo and farmer figure, 500 BCE

Water buffalo and farmer figure, 500 BCE Bronze lamp base

Bronze lamp base Spear and swords, 3rd century BCE

Spear and swords, 3rd century BCE Bronze arrows found at Cổ Loa Citadel

Bronze arrows found at Cổ Loa Citadel

See also

References

- Kiernan 2019, p. 67.

- Đào Duy Anh 2016, p. 32.

- SarDesai 2005, p. 11.

- Hoàng 2007, p. 12.

- Dutton, Werner & Whitmore 2012, p. 9.

- Nam C. Kim 2015, p. 18.

- Kelley 2014, p. 88.

- Taylor 1983, p. 19.

- Terry F. Kleeman 1998, p. 24.

- As quoted in Li Daoyuan's Commentary on the Water Classic,Vol. 37

- Khâm định Việt sử Thông giám cương mục (欽定越史通鑑綱目)

- Đào Duy Anh 2016, p. 30.

- Đào Duy Anh 2016, p. 29.

- Đào Duy Anh 2016, p. 31.

- Brindley 2015, p. 31.

- Wu & Rolett 2019, p. 28.

- Watson 1961, p. 242.

- Taylor 2013, p. 14.

- Miksic & Yian 2016, p. 111.

- Miksic & Yian 2016, p. 156.

- Higham 1996, p. 122.

- Taylor 1983, p. 21.

- Watson 1961, p. 239.

- Yu 1986, pp. 451–452.

- Loewe 1986, p. 128.

- Taylor 1983, p. 24.

- Watson 1961, p. 241.

- Nam C. Kim 2015, p. 5.

- Taylor 1983, p. 25.

- George E. Dutton 2006, p. 70.

- Leeming 2001, p. 193.

- Kelley 2014, p. 89.

- Taylor 2013, p. 15.

- Taylor 2013, p. 16.

- Taylor 2013, pp. 16-17.

- Jamieson 1995, p. 8.

- Brindley 2015, p. 93.

- Buttinger 1958, p. 92.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 69.

- Taylor 2013, p. 17.

- Taylor 1983, p. 28.

- Đào Duy Anh 2016, p. 42.

- McLeod & Nguyen 2001, pp. 15-16.

- Taylor 2013, p. 21.

- Taylor 2013, p. 22.

- Taylor 1983, p. 41.

- Buttinger 1958, p. 77.

- Buttinger 1958, p. 76.

- Taylor 2013, p. 19.

- Ferlus 2009, p. 105.

- Buttinger 1958, p. 75.

- Taylor 1983, p. 10.

- Chapuis 1995, p. 7.

- Taylor 2013, p. 20.

- Baldanza 2016, pp. 43-44.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 71.

- Milburn 2010, p. 31.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 61.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 73.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 63.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 75.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 74.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 51.

- De Vos & Slote 1998, p. 91.

- Kiernan 2019, pp. 51-52.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 92.

- Kim, Lai & Trinh 2010, p. 1011-1027.

Bibliography

- Watson, Burton (1961). Records Of The Grand Historian Of China. Columbia University Press.

- Buttinger, Joseph (1958). The Smaller Dragon: A Political History of Vietnam. Praeger Publishers.

- Leeming, David (2001). A Dictionary of Asian Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195120523.

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-05379-6.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of the Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87586-8.

- SarDesai, D. R. (2005). Vietnam, Past and Present. Avalon Publishing. ISBN 9780813343082.

- Loewe, Michael (1986), "The Former Han dynasty", in Twitchett, Denis C.; Fairbank, John King (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 110–128, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8

- Yu, Ying-shih (1986), "Han foreign relations", in Twitchett, Denis C.; Fairbank, John King (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–463

- Brindley, Erica (2015). Ancient China and the Yue: Perceptions and Identities on the Southern Frontier, C.400 BCE-50 CE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107084784.

- Higham, Charles (1996). The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia. Cambridge World Archaeology. ISBN 0-521-56505-7.

- Wu, Chunming; Rolett, Barry Vladimir (2019). Prehistoric Maritime Cultures and Seafaring in East Asia. Springer Singapore. ISBN 9813292563.

- Li, Tana (2011), "A Geopolitical Overview", in Li, Tana; Anderson, James A. (eds.), The Tongking Gulf Through History, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 1–25, ISBN 9780812205022

- Li, Tana (2011), "Jiaozhi (Giao Chỉ) in the Han Period Tongking Gulf", in Li, Tana; Anderson, James A. (eds.), The Tongking Gulf Through History, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 39–53, ISBN 978-0-812-20502-2

- Hoàng, Anh Tuấn (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Rerlations ; 1637 - 1700. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15601-2.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Introduction to Asian Civilizations. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13862-8.

- De Vos, George A.; Slote, Walter H., eds. (1998). Confucianism and the Family. State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791437353.

- Kelley, Liam C. (2014), "Constructing Local Narratives: Spirits, Dreams, and Prophecies in the Medieval Red River Delta", in Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.), China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia, United States: Brills, pp. 78–106, ISBN 978-9-004-28248-3

- Milburn, Olivia (2010). The Glory of Yue: An Annotated Translation of the Yuejue shu. Sinica Leidensia. 93. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789047443995.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316440551. ISBN 9781316440551.

- Ferlus, Michael (2009). "A Layer of Dongsonian Vocabulary in Vietnamese". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 1: 95–108.

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313296227.

- Terry F. Kleeman (1998). Ta Chʻeng, Great Perfection – Religion and Ethnicity in a Chinese Millennial Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1800-8.

- Jamieson, Neil L (1995). Understanding Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520201576.

- Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Go Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-317-27903-4.

- Kim, Nam; Lai Van Toi; Trinh Hoang Hiep (2010). "Co Loa: an investigation of Vietnam's ancient capital". Antiquity. 84 (326): 1011–1027. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00067041.

- Nam C. Kim (2015). The Origins of Ancient Vietnam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199980895.

- George E. Dutton (2006). The Tay Son Uprising: Society and Rebellion in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824829841.

- Đào Duy Anh (2016) [First published 1964]. Đất nước Việt Nam qua các đời: nghiên cứu địa lý học lịch sử Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Nha Nam. ISBN 978-604-94-8700-2.

- Đào Duy Anh (2020) [First published 1958]. Lịch sử Việt Nam: Từ nguồn gốc đến cuối thế kỷ XIX (in Vietnamese). Hanoi Publishing House. ISBN 978-604-556-114-0.

- McLeod, Mark; Nguyen, Thi Dieu (2001). Culture and Customs of Vietnam. Greenwood (published June 30, 2001). ISBN 978-0-313-36113-5.