Ángela Gurría

Ángela Gurría Davó (born March 24, 1929 in Mexico City) is a Mexican sculptor. In 1974, she became the first female member of the Academia de Artes. She is best known for her monumental sculptures such as Señal, an eighteen meter tall work created for the 1968 Summer Olympics. She lives and works in Mexico City.

Ángela Gurría Davó | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 24, 1929 |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Known for | sculpture |

Life

Gurría was born in Mexico City to a very traditional family from Chiapas.[1][2] Her father, José María Gurría was very strict, not event allowing his wife to leave the house in Coyoacán without him. He had one boy and four girls with his wife, a situation he wanted to change with more boys. However, Angela was the last of their children.[2][3]

As a child, she was attracted to the work done by stonemasons near her home and she wanted to become an artist.[2][4][5] However, in 1940s Mexico it was nearly impossible for a woman to become a professional sculptor. She began by teaching herself.[2][5]

As a young woman, she entered the School of Philosophy and Literature at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México as she had thoughts of becoming a writer. However, she decided to return to art after taking a class in modern art given by Justino Fernández.[1]

Despite prejudices against women at the time, she began her art career. In the early 1960s, she traveled to Europe to study and do research in art, spending time in England, Italy and France. Later she spent time in Greece and New York.[1]

Ángela Gurría lives in Mexico City.[1]

Career

Gurría is one of Mexico's most prolific sculptors. She began her career in the 1960s, achieving success and recognition [3][6] when she dedicated herself to monumental public works in various parts of Mexico.[4]

In 1952, she began to work as an apprentice to sculptor Germán Cueto at Mexico City College, learning from him for six years.[2][3] Later she worked under Mario Zamora at the foundry of Abraham González and at the workshop of Montiel Blancas.[1] However, it was still difficult for women to be taken seriously as sculptors, so she signed her works with male pseudonyms, Alberto Urría or Angel Urría.[2][3] This included her bid for her first monumental piece, called La famila obrera, which was done in 1965.[3] When the organizers of the bid found out she was a women, they were surprised and disgusted, as at the time it will still unthinkable for a woman to do such pieces.[6]

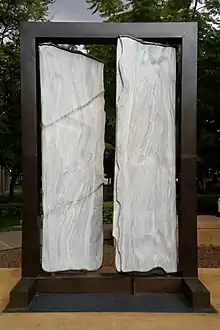

This piece was followed in 1967, by the creation of a latticework door, 18 meters tall and 3.5 meters wide for the main entrance of the factory set up by the Banco de México for the manufacture of bank notes. This work earned her first prize at the III Bienal Mexicana de Escultura.[1]

Her next work is her best known. For the cultural program of the 1968 Summer Olympics, Gurría created a work called Señal, which was placed at the first station of the Ruta de la Amistad (Friendship Route).[2] The sculpture is eighteen meters high, consisting of two horn-like figures, one black and one white. This represents the participation of African countries in the event, for many their first.[3] After the Olympics, the sculpture was moved to a traffic circle on Anillo Periférico in the south of the city.[2] After construction of the second level of this thoroughfare, the sculpture was refurbished and reinaugurated by the artist in 2006.[2][7]

In 1975 she joined the Gucadigose Group to create a monumental work in Tabasco, working with Mathias Goeritz, Juan Luis Díaz, Sebastián, and Geles Cabrera.[1]

Her other important works include Contoy (1974), Monumento México (1974), Trabajadores del Drenaje Profundo (1975), Homenaje a la ceiba (1977), Espiral Serfin (1980), El corazón mágico de Cuzamala (1987) and the sculpted glass Works at the Basilica of Guadalupe in Monterrey (1978-1981).[3][4][5][6]

In addition to the creation of monumental works, she has had a number of exhibitions of her smaller works in museums and other venues. Her first individual exhibition was at the Galerías Diana in 1959,[3] followed by participation in the Escultura Mexicana contemporánea exhibition, organized by Celestino Gorostiza at the Mexico City Alameda Central in 1960.[2] In 1965 she participated in the II Bienal Nacional de Escultura of the Museo de Arte Moderno,[2] and had a major individual exhibition at the Museo de Arte Moderno in 1974.[1] More recently she had another show at the Museo de Arte Moderno in 2004 as well as an exhibition of her work in the atrium of the Temple of San Francisco in the historic center of Mexico City.[5][6]

Her other professional activities include teaching sculpture at the Universidad Iberoamericana and the Universidad de las Américas in Mexico City. In 1969, she worked in industrial design, focusing on carpets with the backing of the Banco de México, since she was interested in creating sources of work for the country’s weavers.[1]

Recognitions for her work and career include an honorary mention at the Exposición de Escultura Mexicana Contemporáneo in 1960, Instituto de Arte de México Prize and the first prize of the III Biennal de Escultura in 1967, first place in sculpture at the Concurso para Monumento in Tijuana in 1973,[5] and the gold medal at the Academia Italia delle Arti e del Lavoro in Italy in 1980.[3] She was accepted as a member of the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana[8] and in 1974 became the first woman to be accepted to the Academia de Artes.[1] In 2008, she was honored at an event at the Soumaya Museum, sponsored by the Fundación del Centro Histórico de la Ciudad de México[4] and in 2010, CONACULTA and the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes honored her at the Palacio de Bellas Artes.[9]

Artistry

Although she came to prominence in the latter 20th century, Gurría is not a member of the Generación de la Ruptura, which rebelled against the artistic precepts of its predecessor, Mexican muralism. The main reason for this was that she spent much of the 1960s working on monumental sculptures with more traditional designs.[4][5] However, she did became one of the pioneers of abstract sculpture in Mexico.[3]

Gurría’s early works were figurative, mystical and even religious in nature.[1][3] Over time, her work evolved to become more abstract. However she never completely left figurative art as natural forms such as the human figure, animals, plants and landscapes still provide the starting points for her forms.[3][5] She is quoted as saying “I define sculpture as an idea that uses form as a point of departure for its own development and space as the element within which the geometry of that idea is expressed.”[1] Concepts present in her work include time, mythology, life/death, Mexican folk art and references to pre-Hispanic cosmology can be found in her work.[5][6] She also works to make her pieces fit harmoniously with the backdrops they are destined for, be it architectural or natural scenery.[5]

Her creations are made from a wide variety of materials including bronze, steel, marble, sandstone, ceramics, iron, volcanic stone and obsidian.[3][5] She is best known for her large and monumental pieces which have reached heights of between thirty and 100 meters, with smaller pieces generally between thirteen and fifteen meters. However, she has created works as small as thirty centimeters.[3][7]

Her later works have not been signed because Gurría says that she is her work.[4]

References

- Guillermo Tovar de Teresa (1996). Repertory of Artists in Mexico: Plastic and Decorative Arts. II. Mexico City: Grupo Financiero Bancomer. p. 124. ISBN 968 6258 56 6.

- Monica Lopez Velarde Estrada (October 2009). "Angela Gurría en rojo". Mexico City: Soumaya Museum. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- "Rinden homenaje a la escultora Ángela Gurría" (Press release). Mexico: CONACULTA. October 23, 2010. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- "Revaloran el trabajo escultórico de Angela Gurría". Mexico City: NOTIMEX. August 24, 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Angela Gurria 1929-". Mexico City: Artes e Historia magazine. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- Germaine Gómez Haro (November 9, 2008). "Ángela Gurría: poesía y monumentalidad". Mexico City: La Jornada Semanal. Retrieved August 1, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Karina Velasco (July 23, 2006). "Recobra Señales de vida escultura de Ángela Gurría". Mexico City: Crónica. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- "Lista de miembros" [List of members] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Salón de la Plástica Mexicana. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- "Rinden homenaje a Ángela Gurría por sus 56 años de trayectoria". La Razón. Mexico City. October 22, 2010. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

External links

- Ángela Gurría in the Ibero-American Institute (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation) catalogue, Berlin