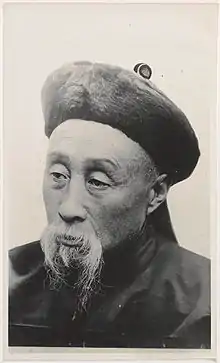

Zhao Erfeng

Zhao Erfeng (1845–1911), courtesy name Jihe, was a Qing Dynasty official and Han Chinese bannerman, who belonged to the Plain Blue Banner. He is known for being the last amban in Tibet, appointed in March, 1908. Lien Yu, a Manchu, was appointed as the other amban. Formerly Director-General of the Sichuan - Hubei Railway and acting viceroy of Sichuan province, Zhao was the much-maligned Chinese general of the late imperial era who led military campaigns throughout Kham (eastern Tibet) and eventually reaching Lhasa in 1910, thus earning himself the nickname "Zhao the Butcher"[1] (Chinese: 赵屠户).[2]

Zhao Erfeng 趙爾豐 | |

|---|---|

Zhao Erfeng | |

| Amban of Tibet | |

| In office 1908–1911 | |

| Monarch | Xuantong Emperor |

| Preceded by | Lianyu |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1845 |

| Died | 1911 Sichuan |

| Cause of death | Decapitation |

| Nationality | Han chinese Bannerman |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Unit | Eight Banners |

| Battles/wars | 1905 Tibetan Rebellion, Chinese expedition to Tibet (1910), 1911 Tibetan Rebellion, Xinhai Revolution |

| Zhao Erfeng | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 趙爾豊 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赵尔丰 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Jihe (courtesy name) | |||||||||

| Chinese | 季和 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Amban of Tibet

Zhao Erfeng crushed the Tibetan Lamas and their monasteries in the 1905 Tibetan Rebellion in Yunnan and Sichuan, he then crushed the rebels at the siege of Chantreng (now Xiangcheng County, Sichuan) which lasted from 1905 to 1906. The Tibetan Lamas had revolted against Qing rule, killing Chinese government officials, western Catholic Christian missionaries and native Christian converts, since the Tibetan Buddhist Gelug Yellow Hat sect was suspicious of the Christian missionary success.

Zhao Erfeng extended Chinese rule into Kham, and was appointed Amban in 1908. Initially he worked with the 13th Dalai Lama, who had returned after fleeing from the British invasion of 1903–1904.[3] But in 1909, they disagreed with each other strongly and Zhao Erfeng drove the Dalai Lama into exile. The Dalai Lama was installed at the palace and monastery of Potala amid popular demonstrations. The ruler, who was again given civil power at the head of their hierarchy, pardoned all the Tibetans who had given the oath to Colonel Younghusband. Things went well for a month until the lama protested to the Chinese in charge of military affairs because of the excesses of the Chinese troops on the Sichuan frontier, where they were sacking the monasteries and killing the monks. This protest served to stir up the whole question of the status of Tibet. The Amban declared that it was a Chinese province, and said he would deal with the rebels as it pleased him to do.

Other questions of authority arose, and finally the Amban sent orders to 500 Chinese troops who were encamped on the outskirts of the capital, Lhasa.

In 1910, China's 'foreign' Manchu Ch'ing dynasty, in a decaying spasm of aggression, had sent two thousand troops under General Chao Er-feng across the border into Tibet. When they arrived in Lhasa they fired on the crowds who had turned out to greet them. On 12 February the 13th Dalai Lama fled towards India pursued by two hundred Chinese cavalrymen, and rode to Phari and then Yatung in the Chumbi Valley, where he was given protection in the Trade Agency...[4]

A few companies composed of the Dalai Lama's followers were hastily enrolled under the name of 'golden soldiers'. They tried to resist the Chinese soldiers, but, being poorly armed, were quickly overwhelmed. Meanwhile, the Dalai Lama, with three of his ministers and sixty retainers, fled through a gate at the rear of the palace enclosure, and were fired upon as they escaped through the city.[5]

In January 1908 the final instalment of the Tibetan indemnity was paid to Great Britain, and the Chumbi valley was evacuated. The Dalai Lama was now summoned to Peking, where he obtained the imperial authority to resume his administration in place of the provisional governors appointed as a result of the British mission. He retained in office the high officials then appointed, and pardoned all Tibetans who had assisted the mission. But in 1909 Chinese troops were sent to operate on the Sichuan frontier against certain insurgent lamas, whom they handled severely. When the Dalai Lama attempted to give orders that they should cease, the Chinese amban in Lhasa disputed his authority, and summoned the Chinese troops to enter the city. They did so, and the Dalai Lama fled to India in February 1910, staying at Darjeeling. Chinese troops followed him to the frontier, and he was deposed by imperial decree.[6]

A former Tibetan Khampa soldier named Aten recounted Tibetan memories of Zhao, calling him "Butcher Feng", claiming that he: razed Batang monastery, ordered holy texts to be used by troops as shoeliners, and mass murdered Tibetans.[7]

Capture and death

In 1911, Zhao Erfeng, then viceroy of Sichuan, faced rebellion in Sichuan. According to Han Suyin, the main issue was control of a planned railway that would have linked Sichuan to the rest of China.[8] He summoned troops from Wuchang, leading rebels there to see it as an opportunity to rebel.[9] This was the background to the Wuchang Uprising, the official start of the Chinese Revolution of 1911. After battling the rebels on 22 December 1911 he was captured and beheaded by Chinese Republican Revolutionary forces who were intent on overthrowing the Qing dynasty.[10][11]

Before his death, Zhao attempted to convene frontier Qing troops on the Sichuan-Tibetan border to Chengdu. He himself, on the other hand, made compromises to the republican forces as if he would concede his power without violence. When the Qing reinforcement from Ya'an approached Chengdu, the head of the republican forces Yin Changheng ordered Zhao's execution.[12]

Zhao Erfeng was the younger brother of Zhao Erxun, who was also an important figure in the final years of the Qing Empire.

Controversies

Zhao's ruthless rule was criticized by later generations. He played an antagonistic role during the Railway Protection Movement and the Miao rebellion in Yongning. Like in Tibet, he massacred unarmed civilians. Both Republic of China and People's Republic of China had fairly negative official comments about Zhao Erfeng, naming him a butcher and homicidal maniac.[13][14][15][16]

Zhao's personal conviction was to transform the region of Kham into a province directly administrated by central government. He planned to unify Sichuan, Kham and Ü-Tsang into a single administrative district in order to counter the British influence in the region as well as Dalai Lama.[17] The bureaucratization of native officers, a policy carried out by Later Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty which deprives the political power of native officers in south western China, was the method Zhao applied to the region of Kham. Consequently, an elimination of Tibetan native rulers in Batang and Litang was implemented.[18][19] By the end of his Tibetan campaign, China was able to seize the region of Kham. However, the control established by Zhao was only temporary. After the fall of Qing dynasty, Tibetans regained the control of most of the lands conquered by Zhao Erfeng.[20] In 1912, after Zhao's death, Chinese troops withdrew from Tibet following the request of the 13th Dalai Lama.[21]

Some historians consider Zhao's Tibetan years as the first Chinese attempt to assimilate Tibet into a regular Chinese province.[21][22] This means a removal of the Tibetan clergy class from their powerful status and a Han Chinese colonization of Tibet.[22]

The aftermath of Zhao's Tibetan expedition caused the region of Kham to become a centre of Tibetan nationalism. In the following years, Lhasa's attempt of unifying Amdo, Kham and Ü-Tsang into the greater Tibet stagnated due to Kham's demand for more power in the Tibetan regime.[22] The Incorporation of Tibet into the People's Republic of China in 1951 eventually ruled out the possibilities of an independent Tibetan nation.

See also

References

Citations

- Arpi, Claude. The Fate of Tibet. Har-Anand Publications.

- 赵尔丰及其巴塘经营

- Thomson, John Stuart (1913). China revolutionized. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. p. 70. OCLC 411755. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

chao ehr feng tibet drove dalai lama out india campaign.

- Hale, Christopher (2004). Himmler's Crusade : the True Story of the 1938 Nazi Expedition into Tibet. London: Bantam. p. 210. ISBN 9780553814453. OCLC 56118412.

In 1910, China's 'foreign' Manchu Ch'ing dynasty, in a decaying spasm of aggression, had sent two thousand troops under General Chao Er-feng across the border into Tibet. When they arrived in Lhasa they fired on the crowds who had turned out to greet them. On 12 February the 13th Dalai Lama fled towards India pursued by two hundred Chinese cavalrymen, and rode to Phari and then Yatung in the Chumbi Valley, where he was given protection in the Trade Agency...

- From The Galveston Daily News, February 7th 1910, part of a newspaper archive.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tibet". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 928.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tibet". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 928. - Jamyang Norbu (1986). Warriors of Tibet: the story of Aten, and the Khampas' fight for the freedom of their country. Wisdom Publications. p. 28. ISBN 0-86171-050-9. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

chao er feng.

- Thomson, John Stuart (1913). China Revolutionized. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. p. 436. OCLC 411755. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

chao ehr feng tibet against the republicans.

- Thomson, John Stuart (1913). China revolutionized. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. p. 317. OCLC 411755. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

chao ehr feng tibet 1910 cooped.

- In The Crippled Tree by Han Suyin, the Wade-Giles spelling of his name, Chao Erfeng, was used.

- Thomson, John Stuart (1913). China Revolutionized. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. p. 35. OCLC 411755. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

chao decapitated.

- 辛亥波涛:纪念辛亥革命暨四川保路运动一百周年文集. Chengdu: Esphere Media. 2015. pp. 232, 233. ISBN 9787545505191.

- 四川省政协文史资料和学习委员会 (10 May 2015). 辛亥波涛:纪念辛亥革命暨四川保路运动一百周年文集. 天地出版社. p. 341. ISBN 978-7-5455-0519-1.

- 張永久 (30 April 2014). 消失的西康. 獨立作家-新銳文創. p. 295. ISBN 978-986-5716-08-0.

- 唯色 (26 June 2015). "張蔭棠與趙爾豐". 立場新聞.

- 《奴才小史》:爾豐怒曰:「我不是趙爾豐,卻是張獻忠,若不開市,與我剿兩條街,則自然皆開市。」此趙屠之諡所由來也。

- "驻藏大臣赵尔丰与西藏". People's Daily. 10 June 2010.

- Wang, Xiaochun (30 May 2016). "见证清政府对川边藏区的改土归流". 中国档案报. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Zhang, Yuxin (2002). 清朝治藏典章硏究, Volume 3. 中国藏学出版社. p. 1465. ISBN 9787800575853.

- Kolas, Ashild; Thowsen, Monika (2011). On the Margins of Tibet: Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier. Washington: University of Washington Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780295804101.

- Lin, Hsaio-ting (2011). Tibet and Nationalist China's Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928-49. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780774859882.

- Akiner, Shirin (1996). Resistance and Reform in Tibet. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 124. ISBN 9788120813717.

Sources

- Adshead, Samuel Adrian M. Province and politics in late imperial China : viceregal government in Szechwan, 1898-1911. Scandinavian Institute of Asian Studies monograph series. no. 50. London: Curzon Press, 1984.

- Ho, Dahpon David. "The Men Who Would Not Be Amban and the One Who Would: Four Frontline Officials and Qing Tibet Policy, 1905-1911." Modern China 34, no. 2 (2008): 210–46.

This article incorporates text from China revolutionized, by John Stuart Thomson, a publication from 1913, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from China revolutionized, by John Stuart Thomson, a publication from 1913, now in the public domain in the United States.