Zhang Dinghuang

Zhang Dinghuang (Chinese: 张定璜; pinyin: Zhāng Dìnghuáng; 1895–1986), also known as Zhang Fengju (Chinese: 张凤举)[1] was born in Nanchang. He was an author, literary critic, and translator, and expert in antique manuscripts (古迹文物). Zhang was a supporting but key figure of the rich 20th c Chinese literary movements.

Zhang Dinghuang | |

|---|---|

张定璜 | |

Zhang in the 1960s, Tokyo | |

| Born | December, 1895 |

| Died | February 2, 1986 Atlanta, Georgia |

| Nationality | Chinese, then American |

| Other names | Zhang Fengju, Chang Feng-Chu, 张凤举 |

| Occupation | Professor at Peking University, Peking Women's Normal University, L'Institude d'etudes Chinois. Ministry delegate to Chinese Occupation Mission in Japan |

| Organization | Ministry of Education, Republic of China |

Notable work | 1920-30s - development of modern Chinese language and literary styles

|

| Spouse(s) | Zhang Huijun 张蕙君 |

| Relatives | Zhang Dingfan (brother) |

| Zhang Dinghuang | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 张定璜 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhang Fengju | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 张凤举 | ||||||

| |||||||

He was a talented multi-linguist who studied in Japan and France, professor at Beijing U and Sino Franco U., also active in the literary scene.

Post-WWII primary figure to recover collection of looted antique manuscripts for Taiwan's National Central Library (literary equivalent of antiques of the Palace Museum).

Career and early years -- 早年

When 15 years old, he enrolled in the Nanchang Army Survey Academy (南昌陆军测绘学堂), following elder brother Zhang Dingfan, an officer in the "Dare to Die" regiment of the Xinhai Revolution. He then attended Kyoto Imperial University. Returning from Japan in 1921 he began his literary and teaching career of the 1920s and 1930s, and activity to develop vernacular Chinese literature.[2]

He taught at Peking Women's College of Education, Peking University, L'Institute des Hautes Etudes Chinoises of the Sorbonne in the 30s, and the Sino-French University in Shanghai. He mastered Japanese, French, and English, which would serve him well decades later. In 1937 he married Zhang Huijun 张蕙君.

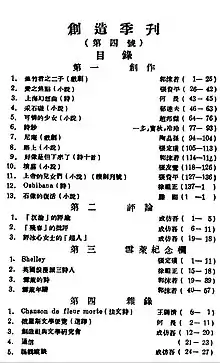

Zhang authored and translated works in French, Japanese and English. Examples include "Shelley" and "Baudelaire".[4][5][6] He worked closely with key figures who shaped the modern Chinese literature and education today.[7] These included Guo Moruo, Cheng Fangwu, Zhang Ziping, Zheng Boqi 郑伯奇, Xu Zuzheng 徐祖正, Shen Yinmo, Lu Xun, and Yu Dafu. All of them participated in the journals Creation Quarterly,[8] Yusi,[9] Contemporary Review, and New Youth. These provided forums for lively and heated discourse on the transition to the vernacular Chinese language; weeklies for short insights or responses, quarterlies for considered and developed ideas. The goal was to bring the written language closer to everyday speech and use subject matter from everyday life. The wiki on "Tattler" has a good summary on this.[10][11] He published "Mr. Lu Xun" in the journal «现代评论» "Contemporary Review", January 1925, a comprehensive and important review of the author still quoted today.

During the 1940s and 50s, he worked for the Education Ministry with a major lasting achievement.[12][13] See Later Years section.

Vignettes 小镜头

- Following the May 4th mass disturbances there were verbal and physical violence for years due to "Beiyan" 北洋 central government. In "Tattler" 语丝, 1925, he commented with a poem titled "Q&A"〈答問〉. It illustrates the Tatler style, fresh, direct and vivid, showing his sarcastic but objective approach.[14]

"" New styles quickly grow the dogmas, From nowhere they kill the winter warmth. Steal at night to sell in day light, This unjust debt cannot be repaid. The new culture speaks fast, Understand or not never mind. Show a lamb head to sell dog meat,

新潮流來的忒快, 平空地把冬烘害. 夜裏偷來晝裏賣. 還不清這冤家債. .新文化要講得快,不懂他倒也沒害。 掛羊頭將狗肉賣, ""

- Zhang Dinghuang wrote an introduction for Feng Zhi 冯至 for his first poems in the journal «创造季刊» "Creation Quarterly" April 6, 1925.[15] A decade later on he was the witness for the 1935 marriage of Feng Zhi 冯至 and Yao Kekun 姚可昆 in Paris.[16][17] Hh

-- Fish and Wine Poetry Feast 鱼酒詠诗会 1937

YGuo Moruo just returned to Shanghai from exile in Japan. His friends, Zhang Fengju 张凤举 with his new bride, Shen Yinmo, his constant companion Zhubaoquan, and Shen Wangsi 沈迈士 enjoyed a fish and wine fest and produced this joint handscroll. Soon after this, Guo joined the Red Army just outside of Shanghai facing the Japanese invasion.[18]

The third paragraph is a joint poem by Shen and Zhang, saying the impromptu verse alternately. Shen begins the first line. Signed by both.

才飲自家酒,酒氣已沖沖。玉箸依然碧,胭脂分外紅。多魚歎今日,凡韻怪茲雄。沫若輸一着,聰明半在躬。 即席聯吟,沫若易末兩語為「賭酒誰之罪,吃虧應反躬」. 尹默 ( Yinmo) 鳳舉 (Fengju)

Only drank my own wine, already heady with drink, the jade chopsticks so green, rouge is extra red, fish abundance for today, Where is the rhyme, Moru steals a look, Clever to bend and bow." (Signed) Yinmo 尹默 and Fengju 凤举. See full text and translation of above scroll here.[19]

-- Another example, a calligraphy fan for gift 墨宝折扇:

Calligraphy fan by Shen Yinmo 沈尹默, Ma Heng and Zhang Fengju It was likely done at a similar occasion and presented to one of the guests.

Later years after 1940 善本古籍由日本回歸

In the 1940s he worked primarily for the Chinese Ministry of Educatin and National Central Library in the areas of antiquities, education and publications. A lasting achievement was to recover the works of the Rare Book Preservation Society (文献保存同志会) which were looted during World War 2. It began with the Yuyuan Road Conferences (愚园路会议) in 1945–1946 to identify the wartime booty that Japan took. Key members included Jiang Fucong, Ma Xulun, Zheng Zhenduo, and Zhang Fengju. Official Yuyuan Road 愚园路会议 Ministry conference minutes shows signatures of the conference attendees. Zhang Fengju 张凤举 is the lower signature of the 1st line .

March 23, 1946, the Ministry appointed Zhang Fengju to the Chinese Occupation Mission in Japan as head of the 4th Section (Education and Culture). He left for Tokyo on April 1 and began discussions with the U.S. Command General Headquarters (GHQ) the next day. Because of his gift in languages and his participation in the original preservation effort[20] he held substantive meetings with all parties without translators. In 2 months, over 135,000 volumes were retrieved. By the year's end they were back in the hands of the National Central Library where they form the core of the rare books collection today. Many other university and museum collections were also retrieved.

After 1949 and with the excesses which followed the Chinese Civil War, his closest friends and associates from the early years were on the mainland. His closest recent associates were in Taiwan. He himself favored neither side and preferred non-violence. He didn't participate in any government activities after 1960 but kept in touch with a network of old friends in Taiwan and U.S. including Li Shu-hua 李书华, Zhu Jiahua 朱家骅, Gu Mengyu 顾孟余, Y. H. Ku, Zhu Shiming 朱世明, Shang Zhen.. . Moved to the US with his wife in 1965 to join his children. Died February 2, 1986 in Atlanta.

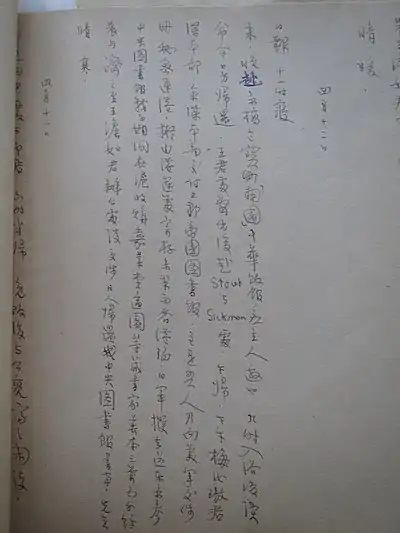

Personal handwritten diaries pages and reports now at National Central Library 中央圖書館, Taipei 張鳳舉日記 選[20]

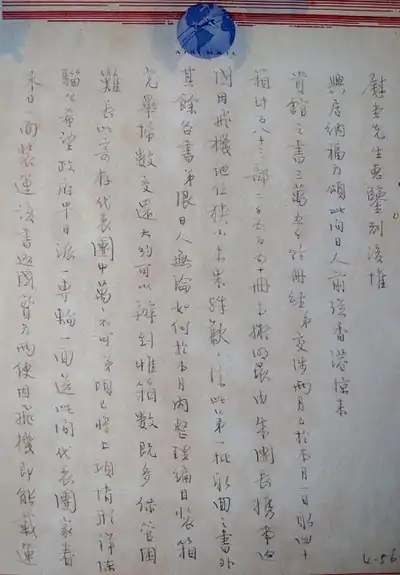

These contain details of the recovery of looted manuscripts and books fromTokyo. Summarizing, the diary begins on April 1. He goes to Tokyo as part of the Chinese Occupation Mission headed by General Zhu Shiming on April 1, 1946. He knew many of the Japanese experts from his days at Kyoto Imperial University. His direct personal meetings from April 2, 1946 quickly bear fruit. A major portion was located in the Ueno Imperial Library on April 8. On April 11, he requests an official directive from the U.S. Supreme Command for the return of the collections: File:Issue Order to Return Manuscripts. Ret-xIMG 0006.jpg . The looted collections from the Rare book Preservation Society were in the Chinese Mission in Tokyo by June, and shipped to Shanghai by December. There were other collections as well as donations from Japanese institutions. Two months later, this is his official June 5: report to the Education Ministry and the National Central Library .

Partial quote: "After 2 months of negotiations, we got 40 crates on June 1. Planned to ship 18,000 volumes (about 255,000 books) on General Zhu's trip. But the airplane was too small. Humble apologies. Beyond this first batch, I have required the Japanese to complete the detailed inventory list, the packaging and return all by the end of this month. Probably can be achieved."[21]

Important contributions

- Active participant in the movement to modernize the Chinese language see discussion in "Tattler" 语丝, a literary journal.[22][23] A founder of "Creation Quarterly" in Tokyo 1921.

- He recognized the importance of Lu Xun early and published a long paper titled "Mr. Lu Xun" in the journal «现代评论» "Contemporary Review", January 1925, still a standard about the author.[21] The paper coined the phrase "Mr. Lu Xun" 鲁迅先生. He also established the concept "乡土文学" (peasant dirt literature).[24]

- Personified the style "Personal Novel" (“身边小说”).

- Helped many younger writers including the modern poet Feng Zhi 冯至 publish his work. Introduced his first group of poems《归乡》"Return" in the journal «创造季刊» "Creation Quarterly", 1925.[25]

- Rare Book Preservation Society member. Preserved collections of antique manuscripts during the Japanese occupation of China in WWII.

- Recovered large quantities of collections and antiquities including over 130,000 volumes of the above. He also persuaded Japanese institutions to donate journals and books to institutions in China.)[20]

References

- "360百科".

- "5. Feng's Vernacular Fiction", The Chinese Vernacular Story, Harvard University Press, 1981, doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674418462.c5, ISBN 9780674418462

- "书法大家" [Calligraphy everyone]. ifeng.com.

- "Britishlibrary.com".

- Bien, Gloria (2012-12-14). Baudelaire in China: A Study in Literary Reception. ISBN 9781611493900.

- 张旭春 (2004). 政治的审美化与审美的政治化 [Political Aestheticization and Aesthetic Politicization]. Duke University Libraries, University of Michigan: 人民出版社. ISBN 7010040907. 9787010040905.

- 杨联芬 (2003). 晚清至五四: 中国文学现代性的发生 [Late Qing to May 4th: The Occurrence of Modernity of Chinese Literature]. 北京大学出版社. ISBN 7301065663. 9787301065662.

- 咸立强 (2006). 寻找归宿的流浪者/创造社研究/"中国现代文学社团史"研究书系: 创造社研究 [Looking for the Wanderer/Creation Society Research/"Chinese Modern Literature Society History" Research Book Series: Creation Society Research]. 东方出版中心. ISBN 7801864697. OCLC 71775354. 9787801864697.

- 在"我"与"世界"之间: 语丝社研究 [Between "I" and "World": The Study of the Language Society]. 东方出版中心. 2006. ISBN 7801864727. 9787801864727.

- 北京报刋史话 [Beijing Baoji History. ]. 文化藝術出版社., - Chinese newspapers - 214 pgs. 1992. pp. 93.黄河 (Yellow River).

- 宋彬玉, 张傲卉 (1998). 创造社十六家评传 [Creation Society 16 Reviews]. 重庆出版社. p. 357. ISBN 7536640757.

- "華人百科" [Chinese encyclopedia].

- "easyatm.com.tw".

- 《從學生運動到運動學生》 [From the student movement to the movement of students.] (in Chinese). National Central Library. 1994. ISBN 9576712254.

- "王朝网络" [Dynasty network].

- "冯至 -人物百科 翻译百科" [Feng Zhi - Character Encyclopedia]. China.

- 周良沛 (2001). 冯至评传 [Feng Zhi's biography]. Library of Congress, Princeton University Library: 重庆出版社. ISBN 7536651848. 9787536651845.

- 龔明德 (2015). 民國文人私函真跡解密 [The official letter of the Republic of China]. 独立作家. p. 116. ISBN 978-9865729196.

- "Old Friends Fish & Wine Poetry Feast, Shanghai 鱼酒唱和会手卷". Flickr.

- "Rare Book Preservation Society". Wikipedia.

- Journal at National Central Library library 国家中央图书馆 台北 catalogue P 050 8564

- 陈离 (2006). 在"我"与"世界"之间: 语丝社研究 [Between "I" and "World": The Study of the Language Society. Oriental Publishing Center]. 东方出版中心. p. 307. ISBN 7801864727. 9787801864727.

- CHEN LI (June 1, 2006). Between me and the world : social studies Tattler (Chinese ed.). Oriental Publishing Center; 1 edition. ISBN 9787801864727.

- 李松睿 (2017). 文學的時代印痕:中國現代文學論集 [The Imprint of the Age of Literature: A Collection of Modern Chinese Literature]. 北京時代華文書局. ISBN 978-7569913613. 9787569913613.

- 周良沛 (2001). 冯至评传 [Feng Zhi's biography]. Library of Congress: 重庆出版社. pp. 92–94, 349. ISBN 7536651848.