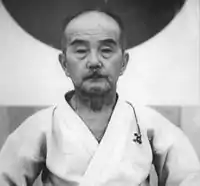

Yasuhiro Konishi

Yasuhiro Konishi (小西康裕, Konishi Yasuhiro, 1893 - 1983) was one of the first karateka to teach karate on mainland Japan. He was instrumental in developing modern karate, as well as a driving force in the art's acceptance in Japan. He is credited with developing the style known as Shindō jinen-ryū (神道自然流).

| Yasuhiro Konishi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1893 Takamatsu, Kagawa, Japan |

| Died | 1983 (aged 89–90) Tokyo, Japan |

| Style | Shindō Jinen Ryū |

| Teacher(s) | Gichin Funakoshi, Choki Motobu, Kenwa Mabuni, Morihei Ueshiba, Chojun Miyagi, Chōshin Chibana |

| Rank | Sōke, Founder of Shindō jinen-ryū |

| Notable students | Kiyoshi Yamazaki, Sho Kosugi, Shoji Nishio |

| Website | Japan Karate Do Ryobu-Kai |

Early life

Yasuhiro Konishi was born in 1893 in Takamatsu, Kagawa, Japan. In 1899 he began training in Muso Ryu jujutsu, then kendo when he was 13 and later, Takenouchi-ryū jujutsu and judo. In 1915, he entered Keio University in Tokyo.

Konishi's first exposure to te was through Tsuneshige Arakaki, who was from Okinawa. Konishi quit his job in 1923 to open a martial arts center. Naming his dojo the Ryobu-Kan ("The House of Martial Arts Excellence"), Konishi provided instruction in kendo and jujutsu.[1]

Training with Japanese Masters

In September 1924, Hironori Ohtsuka and Gichin Funakoshi came to the Keio University kendo training hall. With Konishi's help, Funakoshi established a to-te club at Keio University. Konishi, Funakoshi and Ohtsuka were the instructors and with the addition of te to Konishi's curriculum of jujutsu, kendo and western boxing, modern karate was born.[2]

Training with Okinawan Masters

As karate gained popularity, a number of Okinawan masters traveled to Japan. Many of these martial artists visited the Ryobu-Kan. Among them were Choki Motobu, Kenwa Mabuni and Chojun Miyagi.

Konishi considered Motobu a martial arts genius and trained with him often. A native of Okinawa, Motobu did not speak Japanese well.[2] Konishi trained less frequently with Miyagi but Miyagi presented him with a manuscript, "An Outline of Karate-Do", dated March 23, 1934.[3] Konishi trained with Kenwa Mabuni, who resided at Konishi's house for ten months in 1927 and 1928. Mabuni was known for his knowledge of kata. Mabuni and Konishi later worked together to develop the kata Seiryu.

The Influence of Morihei Ueshiba

Konishi also studied under Morihei Ueshiba. Konishi demonstrated Heian Nidan to Ueshiba who opined that Konishi should cease pursuing such ineffective techniques.

Konishi created a kata he named Tai Sabaki (“body movement”). A notable difference from most karate kata was that it was an unbroken sequence of actions.[4] Morihei Ueshiba remarked, "The demonstration you did just now was satisfactory to me and that kata is worth mastering." Konishi would later develop two more forms based on the same principles, and he named these three kata Tai Sabaki Shodan, Tai Sabaki Nidan and Tai Sabaki Sandan.[1]

Seiryu (青柳) Kata

During the 1930s, the Japanese government was largely controlled by the military, and around 1935, the commanding general of the Imperial Japanese Army approached Konishi and asked him to develop self-defense techniques for women serving in the Japanese Government Railways.[5] At the time, Konishi, Ueshiba, Mabuni and Ohtsuka were training together almost every day, and Konishi asked Mabuni to work with him on delivering what the government had requested.

Together, the two men developed a kata incorporating significant elements of their respective styles, Shindō jinen-ryū and Shito-Ryu, as well as feedback from Morihei Ueshiba, who advised them on changes intended to more closely tailor the techniques included in the form to the needs of women, for whom it was being designed. The kata that resulted from the collaboration between these three masters - Seiryu (青柳, meaning Green Willow) - includes core principles from karate, aikido and jujutsu, and became part of the training regiment for female railway workers.

World War II and Karate

With Japan embroiled in World War II, the continued evolution and refinement of karate plateaued as many practitioners enlisted to fight for their country. With Japan's surrender in 1945, however, the nation's male population returned, only to encounter a prohibition on the practice of all martial arts (with the exception of sumo) that had been ordered by Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Allied Occupation. As life slowly returned to normal, MacArthur's ban was lifted, and Konishi worked diligently to revive the practice of both kendo and karate.

Later Recognition

Like Morihei Ueshiba, Konishi used budō training in his personal quest to build character while creating harmony between body, mind, and art. He believed karate and Zen are different aspects of the same thing, and expressed that conviction in a short poem:[6]

- Karate is

- Not to hit someone

- Nor to be defeated

- It is to avoid trouble

While less famous than many of his contemporaries outside Japan, Konishi is today recognized as one of history's most significant budō masters. He was a successful businessman, teacher, and political activist, who strove to bring respectability to martial arts, and his efforts are a major reason that karate enjoys the position it does today. Konishi died in 1983.[3]

Sources

- Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts, Volume 2: Koryu Uchinadi by Patrick McCarthy [Book]. Boston, MA: Tuttle Publishing. 1999

- Japanese Karate, Volume 1: Shindo Jinen Ryu. [Motion Picture]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Tsunami Productions. 1998

- Japanese Karate, Volume 2: Ryobukai and Shotokan. [Motion Picture]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Tsunami Productions. 1998

- Japan Karate-Do Ryobu-Kai Instructors Manual. 1996

- Black Belt Karate by Chris Thompson [Book]. London, UK: New Holland Publishers. 2008

References

- Shindo Jinen-Ryu by Howard High at Dragon Times

- Excerpts from "Old Grand Master Yasuhiro Konishi: Karate and his Life” by Kozo Kazu

- "Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts, Volume 2: Koryu Uchinadi" by Patrick McCarthy at Google Books

- Tai Sabaki Shodan at www.jkr.com

- Seiryu at www.jkr.com

- Shindo Jinen-Ryu Karate-Do History and Tradition of Budo at FightingArts.com