Women's Library

The Women's Library is England's main library and museum resource on women and the women's movement, concentrating on Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries. It has an institutional history as a coherent collection dating back to the mid-1920s, although its "core" collection dates from a library established by Ruth Cavendish Bentinck in 1909. Since 2013, the library has been in the custody of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), which manages the collection as part of the British Library of Political and Economic Science in a dedicated area known as the Women's Library.

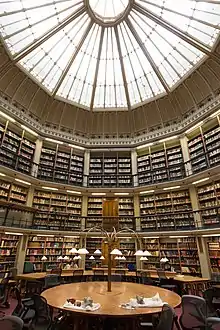

The Women's Library reading room in the LSE library | |

| Country | England |

|---|---|

| Type | Library |

| Established | 1926 |

| Location | Lionel Robbins Building, The London School of Economics and Political Science, 10 Portugal Street, Westminster, London, WC2A 2HD |

| Collection | |

| Items collected | Books, journals, newspapers, magazines, sound and music recordings, archives, pamphlets, drawings and manuscripts |

| Size |

|

| Access and use | |

| Access requirements | Open to anyone with a need to use the collections and services and those coming to see exhibitions |

| Website | The Women's Library |

| Map | |

| |

Collections overview

The printed collections at the Women's Library contain more than 60,000 books and pamphlets, more than 3,500 periodical titles (series of magazines and journals), and more than 500 zines. In addition to scholarly works on women's history, there are biographies, popular works, government publications, and some works of literature. There are also extensive press cutting collections.[1]

The Library's museum collection holds more than 5,000 objects, including over 100 suffrage and modern campaigning banners, photographs, posters, badges, textiles, and ceramics. There are more than 500 personal and organisational archives, ranging in size from one to several hundred boxes.[1]

In February 2007, the Women's Library collections were designated by the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council for their "outstanding national and international importance" (the Designation Scheme is now overseen by the Arts Council).[2] In 2011, items from the women's suffrage archives held at The Women's Library were inscribed in UNESCO's UK Memory of the World Register as the "Documentary Heritage of the Women's Suffrage Movement in Britain, 1865–1928".[3]

History

London Society for Women's Suffrage/Fawcett Society

The Women's Library traces its roots to the London Society for Women's Suffrage, a group established in 1867 to campaign for the right to vote. The "core" collection[4] was the Cavendish-Bentinck library that was founded in 1909 by Ruth Cavendish Bentinck.[5] The collection was organised by the inaugural librarian, Vera Douie, who was appointed on 1 January 1926. At this time, and for many years afterward, it was called the Women's Service Library, in accordance with the name of the society which since the outbreak of World War I had been called the London Society for Women's Service. Douie remained in post for 41 years, during which time she took a small but interesting society library and turned it into a major resource with an international reputation.

It was originally housed in a converted public house in Marsham Street, Westminster, which in the 1930s was developed into Women's Service House, a major women's centre within walking distance of Parliament. Members of the society and library included writers such as Vera Brittain and Virginia Woolf, as well as politicians, most notably Eleanor Rathbone. Woolf wrote about the Library to Ethel Smyth: "I think it is almost the only satisfactory deposit for stray guineas [money]".[6]

During World War II it suffered bomb damage, and the library had no permanent home until 1957, when it moved to Wilfred Street, near Victoria railway station. By this time, the society and library had changed their names to the Fawcett Society and the Fawcett Library, in commemoration of the non-militant suffrage leader Millicent Garrett Fawcett, and of her daughter, Philippa Fawcett, an influential educationist and financial supporter of the society.

City of London Polytechnic/London Guildhall University/London Metropolitan University

In the 1970s the Fawcett Society found it increasingly difficult to maintain the library. In 1977 it was taken over by the City of London Polytechnic, which in 1992 became London Guildhall University. The library subsequently spent nearly 25 years in a cramped basement increasingly liable to flooding, while increasing considerably its stock, its user base and its contacts with other such resources both nationally and internationally.

It became increasingly apparent that these facilities were not adequate to store the collection, and a project was launched to improve the housing of the material and increase access to the library by members of the general public. In 1998 the Heritage Lottery Fund awarded a grant of £4.2 million to the University for a new library building. The site chosen, in Old Castle Street, Aldgate, in the East End of London, used to be a wash house, a place of women's labour, and the architects maintained its facade. Changing its name from the "Fawcett Library" to the "Women's Library", the new institution opened to the public in February 2002.[7] Its new purpose-built home by Wright & Wright Architects, encompassing a reading room with open stacks, an exhibition hall, several education spaces, and specialist collection storage, was the recipient of an award from the Royal Institute of British Architects.[8] In August of the same year, London Guildhall University merged with the University of North London to become London Metropolitan University.

Under the auspices of LMU, the Women's Library hosted a changing programme of exhibitions in its museum space; topics included women's suffrage, beauty queens, office work, 1980s politics, women's liberation, women's work and women's domestic crafts. Its exhibition and education programme on prostitution was long-listed for the 2007 Gulbenkian Prize.[9] It held public talks, showed films, ran reading groups and short courses, offered guided tours, and worked with schools and community groups.

Three individuals were recognised by the UK honours system for their work with the library: Vera Douie OBE;[10] David Doughan MBE (Services to Women's Studies);[11] and Jean Florence Holder MBE (for voluntary service to the Women's Library).[12]

London School of Economics

.jpg.webp)

In spring 2012, London Metropolitan University, arguing that too much of the library's usage came from outside the university, announced that it had decided to attempt to find a new home, owner or sponsor for the library's holdings, and threatened to reduce services to one day per week if such a sponsor could not be found. The University also hoped to convert the library building to house a lecture theatre.[13] A Save the Women's Library Campaign was set up by the London Met branch of UNISON. It aimed to keep the Women's Library's collections intact, retain the expertise of its staff, and remain in its dedicated building.[14] A petition opposing the curtailment or closure of the library ultimately attracted more than 12,000 signatures. It called the Women's Library "one of the most magnificent specialist libraries in the world" and a "national asset".[15]

The University invited bids from interested institutions, and the proposal of the London School of Economics (LSE) was found the most acceptable. It guaranteed to preserve, maintain and develop the collections as an individual entity within the British Library of Political and Economic Science, with a dedicated reading room and archival space. The LSE also offered continued employment to members of permanent staff who wished to remain with the library. The transfer became effective on 2 January 2013. The existing building was not handed over, but remained part of London Metropolitan University.

Major collections

Personal archives held at the Women's Library include those of Lesley Abdela, Adelaide Anderson, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Margery Corbett Ashby, Lydia Becker, Helen Bentwich, Rosa May Billinghurst, Chili Bouchier, Elsie Bowerman, Josephine Butler, Barbara Cartland, Jill Craigie, Emily Wilding Davison, Charlotte Despard, Emily Faithfull, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Vida Goldstein, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elspeth Howe, Mary Lowndes (see also Artists' Suffrage League Papers), Constance Lytton, Harriet Martineau, Edith How-Martyn, Angela Mason, Hannah More, Helena Normanton, Eleanor Rathbone, Claire Rayner, Sheila Rowbotham, Maude Royden, Myra Sadd Brown, Nancy Seear, Baroness Seear, Elaine Showalter, William Thomas Stead, Mary Stott, Louisa Twining and Henry Wilson.

Organisation and campaign archives include the Fawcett Society, the Artists' Suffrage League, several sets of papers related to the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp, the International Alliance of Women, Miss Great Britain, the London Society for Women's Suffrage, the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, the National Women's Register, One Parent Families, Gingerbread, campaigns for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, especially the Association for Moral and Social Hygiene, the International Council of Women, the Open Door Council, the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service, the Six Point Group, the Women's Freedom League, Women in Black UK, the National Federation of Women's Institutes, the Women's National Anti-Suffrage League and the Women's Tax Resistance League.

Friends of the Women's Library

The Friends of the Women's Library have also played a vital role in promoting and ensuring the continued growth and recognition of The Women's Library. The Friends of The Women's Library have supported the library for more than 30 years, and through many changing circumstances. The members raise much needed funds for the enhancement of the collections, and have purchased rare items at auction, financed the digitisation of recorded interviews, and sponsored exhibitions. They also organise visits to places and collections of special interest in British women's history.[16]

See also

- Feminist Library, also in London

- Fawcett Society, a UK-wide charity and pressure group

- Glasgow Women's Library

- Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom

- Women's writing (literary category)

- East End Women's Museum

References

- "About The Women's Library @ LSE collection". The London School of Economics. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Double celebration for The Women's Library". London Metropolitan University. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "UNESCO recognition for Women's Library". London Metropolitan University. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Crampton, Caroline (15 May 2014). "The Women's Library: a treasure house of women's literature". New Statesman. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Doughan, David, "Bentinck, Ruth Mary Cavendish- (1867–1953)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Snaith, Anna (December 2002). "'Stray Guineas': Virginia Woolf and the Fawcett Library" (PDF). Literature & History. Third: 16–35.

- "Women's Library finds home". BBC News. 1 February 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "The Women's Library wins architecture prize". London Metropolitan University. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "The Women's Library, London Metropolitan University: Prostitution: What's Going On?". The Gulbenkian Prize. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Fellowships". The Women's Library, London Metropolitan University. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- "New year's honours". Times Higher Education. 5 January 2001. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- "New Year honours list: MBEs". The Guardian. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- Atkinson, Rebecca (10 April 2012). "Campaign to save the Women's Library". Museums Journal. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "A Vindication of the Rights of the Women's Library". Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Flood, Alison (11 April 2012). "Women's Library campaign gathers steam". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Who we are". Friends of the Women's Library. Retrieved 17 January 2015.