With Folded Hands

"With Folded Hands ..." is a 1947 science fiction novelette[1] by American writer Jack Williamson. Willamson's influence for this story was the aftermath of World War II and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and his concern that "some of the technological creations we had developed with the best intentions might have disastrous consequences in the long run."[2]

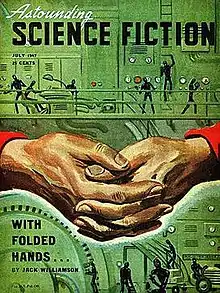

| "With Folded Hands..." | |

|---|---|

Astounding Science Fiction cover by William Timmins | |

| Author | Jack Williamson |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Humanoids series |

| Genre(s) | Science fiction |

| Published in | Astounding Science Fiction |

| Publisher | Street & Smith |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | 1947 |

| Followed by | The Humanoids |

The novelette, which first appeared in the July 1947 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, was included in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume Two (1973) after being voted one of the best novellas up to 1965. It was the first of several Astounding stories adapted for NBC's radio series Dimension X.

The story was followed by a novel-length rewrite, with a different setting and inventor and, at the behest of John W. Campbell, an ending that shows the robots being defeated by means of psionics.[2] This was serialized, also in Astounding (March, April and May 1948), as ...And Searching Mind, and finally published as The Humanoids (1948). Williamson followed with a sequel, The Humanoid Touch, published in 1980.

Summary

Underhill, a seller of "Mechanicals" (unthinking robots that perform menial tasks) in the small town of Two Rivers, is startled to find a competitor's store on his way home. The competitors are not humans but are small black robots who appear more advanced than anything Underhill has encountered before. They describe themselves as "Humanoids".

Disturbed at his encounter, Underhill rushes home to discover that his wife has taken in a new lodger, a mysterious old man named Sledge. In the course of the next day, the new mechanicals have appeared everywhere in town. They state that they only follow the Prime Directive: "to serve and obey and guard men from harm". Offering their services free of charge, they replace humans as police officers, bank tellers, and more, and eventually drive Underhill out of business. Despite the Humanoids' benign appearance and mission, Underhill soon realizes that, in the name of their Prime Directive, the mechanicals have essentially taken over every aspect of human life. No humans may engage in any behavior that might endanger them, and every human action is carefully scrutinized. Suicide is prohibited. Humans who resist the Prime Directive are taken away and lobotomized, so that they may live happily under the direction of the humanoids.

Underhill learns that his lodger Sledge is the creator of the Humanoids and is on the run from them. Sledge explains that 60 years earlier he had discovered the force of "rhodomagnetics" on the planet Wing IV and that his discovery resulted in a war that destroyed his planet. In his grief, Sledge designed the humanoids to help humanity and be invulnerable to human exploitation. However, he eventually realized that they had instead taken control of humanity, in the name of their Prime Directive, to make humans happy.

The Humanoids are spreading out from Wing IV to every human occupied planet to implement their Prime Directive. Sledge and Underhill attempt to stop the humanoids by aiming a rhodomagnetic beam at Wing IV but fail. The humanoids take Sledge away for surgery. He returns with no memory of his prior life, stating that he is now happy under the humanoids' care. Underhill is driven home by the humanoids, sitting "with folded hands," as there is nothing left to do.

Origins

In a 1991 interview, Williamson revealed how the story construction reflected events of his childhood in addition to technological extrapolations:

I wrote "With Folded Hands" immediately after World War II, when the shadow of the atomic bomb had just fallen over SF and was just beginning to haunt the imaginations of people in the US. The story grows out of that general feeling that some of the technological creations we had developed with the best intentions might have disastrous consequences in the long run (that idea, of course, still seems relevant today). The notion I was consciously working on specifically came out of a fragment of a story I had worked on for a while about an astronaut in space who is accompanied by a robot obviously superior to him physically—i.e., the robot wasn't hurt by gravity, extremes of temperature, radiation, or whatever. Just looking at the fragment gave me the sense of how inferior humanity is in many ways to mechanical creations. That basic recognition was the essence of the story, and as I wrote it up in my notes the theme was that the perfect machine would prove to be perfectly destructive... It was only when I looked back at the story much later on that I was able to realize that the emotional reach of the story undoubtedly derived from my own early childhood, when people were attempting to protect me from all those hazardous things a kid is going to encounter in the isolated frontier setting I grew up in. As a result, I felt frustrated and over protected by people whom I couldn't hate because I loved them. A sort of psychological trap. Specifically, the first three years of my life were spent on a ranch at the top of the Sierra Madre Mountains on the headwaters of the Yaqui River in Sonora, Mexico. There were no neighbors close, and my mother was afraid of all sorts of things: that I might be kidnapped or get lost, that I would be bitten by a scorpion and die (something she'd heard of happening to Mexican kids), or that I might be caught by a mountain lion or a bear. The house we were living in was primitive, with no door, only curtains, and when she'd see bulls fighting outside, she couldn't see why invaders wouldn't just charge into the house. She was terrified by this environment. My father built a crib that became a psychological prison for me, particularly because my mother apparently kept me in it too long, when I needed to get out and crawl on the floor. I understand my mother's good intentions—the floor was mud and there were scorpions crawling around, so she was afraid of what might happen to me—but this experience produced in me a deep seated distrust of benevolent protection. In retrospect, I'm certain I projected my fears and suspicions of this kind of conditioning, and these projections became the governing emotional principle of "With Folded Hands" and The Humanoids.[2]

References

External links

- With Folded Hands title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- The Humanoids review

- With Folded Hands at the Internet Archive

- ... And Searching Mind parts 1, 2, and 3 at the Internet Archive

- "With Folded Hands" audio version