Winchester Psalter

The Winchester Psalter is an English 12th-century illuminated manuscript psalter (British Library, Cotton MS Nero C.iv), also sometimes known as the Psalter of Henry of Blois, and formerly known as the St Swithun's Psalter. It was probably made for use in Winchester, most scholars agreeing that the most likely patron was the Henry of Blois, brother of Stephen, King of England, and Bishop of Winchester from 1129 until his death in 1171. Until recent decades it was "a little-studied masterpiece of English Romanesque painting",[1] but it has been the subject of several recent studies.

The manuscript now has 142 vellum leaves of 32 x 22.25 cm, which after a fire in 1731 have been cut and mounted individually, and rebound.

Miniatures

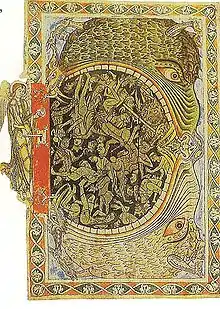

The thirty-eight full-page miniatures are all grouped at the beginning of the manuscript. They are nearly all divided horizontally into two or three compartments with different scenes, creating an unusually extended narrative cycle of more than eighty scenes covering the Old Testament (6 pages), the Life of the Virgin and Life of Christ (23 pages) and several scenes covering the Second Coming and Last Judgement (9 pages) - a number of non-narrative subjects such as the Jesse Tree, Christ in Majesty and an enthroned Virgin being included in these figures. Together they form "one of the most unusual and innovative miniature cycles of the twelfth century"[2]

Most of the miniatures are drawings tinted with coloured washes set against fully painted backgrounds. This is a common English technique from at least the 11th to the 13th century. Two miniatures, of the Death of the Virgin and the Virgin Enthroned, are in a different fully painted technique and style, and follow Byzantine iconographic models, although the forms of the drapery are English in style.[3] The other miniatures are all closely related to one another in style, though some are of markedly higher quality than others. According to Heslop, this is deliberately done to reflect the social status of the subjects depicted;[4] Haney considers it may be the result of an artist working closely with a less skilled assistant.[5] Apart from the two "Byzantine" miniatures, all the others have borders of geometric ornament, onto which the central image sometimes impinges. Many scenes or parts of scenes are just drawn in ink, presumably unfinished, especially towards the end of the cycle. Some paint has been added to areas by a less skilled artist, probably a few decades after the original work.[6] Many miniatures have titles in Norman-French, in a different hand to the main text, probably added later in the 12th century.[6] The original sequence of the miniatures is uncertain.

Haney's analysis of the iconography of the cycle suggests a variety of sources and influences were involved. Some details can be found in Early Christian works such as the Cotton Genesis but not in works from later periods. Other details show awareness of Carolingian and Ottonian traditions, while much else continues Anglo-Saxon and English Romanesque iconography.[7]

Contents

The manuscript contains:

- (fols 2r–39r) 38 full-page miniatures

- (fols 40r–45v) Calendar illustrated with Labours of the Months and Zodiac Signs

- (fols 46r–123v) Psalms 1-150, in parallel Latin and French versions, with decorated or historiated initials at the major divisions

- (fols 123v–132r) Canticles, Gloria, Lord's Prayer, and Creeds

- (fol 132r–v) Litany

- (fols 133v–134r) Fourteen collects

- (fols 134r–142v) Thirty-six prayers

- (fol 142v) A rubric introducing a text that is now missing from the volume

Patron

Several pieces of evidence suggest that the patron was Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester from 1129 to 1171:

- Feasts in the calendar suggest it was made for Winchester

- Two feasts in the calendar suggest a connection with Cluny Abbey; Henry of Blois had formerly been a monk of Cluny,

- The presence and absence of feasts in the calendar suggest that it was made between 1120 and 1173, or before 1161 according to Wormold and Haney, as the Calendar lacks the feast of Edward the Confessor, canonized in that year,[8]

- One of the Latin prayers is addressed to St Swithun, patron saint of Winchester Cathedral, whose relics were in the cathedral; the prayer mentions "sanctis quorum corpora in hac iuxta te requiescunt aula" (saints whose bodies rest in this church next to you)

Some pieces of evidence suggest instead that the manuscript was not made for Henry of Blois, and may instead have been made for a woman, although the personal Latin prayers use masculine forms:[9]

- Most 12th-century psalters with series of full-page pictures were apparently made for women

- The Litany is not a normal litany of Winchester, but is closely related to the litany of Abingdon Abbey

- The litany has a number of female saints who would not be expected in a litany of Abingdon, three of whom are the main saints of the nunnery of Barking Abbey

- By about the middle of the 13th century the manuscript was at the nunnery of Shaftesbury Abbey, to judge by a series of additions made to the calendar

History

It is not known where the manuscript was between the 13th century and 1638, when it appears in a catalogue of the collection formed by the antiquary Sir Robert Cotton between about 1588 and 1629, and added to by his son and grandson.[10] The manuscript was damaged in the fire in 1731 at Ashburnham House in which many of the Cotton manuscripts were damaged. As a result, the bifolia were split into single leaves, and there is some uncertainty about their original sequence, which has been partly resolved by the recent discovery of verdigris offsets which confirm which miniatures originally faced each other.[11] Cotton's library formed one of the foundation collections of the British Museum, from which the British Library was formed in 1973. The manuscript was on semi-permanent exhibition at the British Museum, but is now very rarely exhibited at the new St Pancras site of the British Library.

Notes

- Haney, xix

- Haney

- Haney, 125

- Heslop, 1990

- Haney, 2-4

- Haney, 13-14

- Haney, Chapter II in particular, especially pp. 15-30

- Haney, 8

- Haney, 8 (on the prayers only)

- Haney, 9

- Haney, 9-12

Literature

- Dodwell, C.R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800-1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

- Evans, Helen C. & Wixom, William D., The glory of Byzantium: art and culture of the Middle Byzantine era, A.D. 843-1261, no. 312, 1997, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780810965072; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Haney, Kristine Edmondson, The Winchester Psalter; an iconographic study, 1986, Leicester University Press, ISBN 0-7185-1260-X. All the miniatures are reproduced.

- Heslop, Thomas Alexander, 'Romanesque painting and social distinction: the Magi and the shepherds', in England in the Twelfth Century, Proceedings of the 1988 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. by Daniel Williams (1990), pp. 137–52.

- C. M. Kauffmann, Romanesque manuscripts: 1066-1190. ed. by J. J. G. Alexander (London, 1975), no. 78.

- Francis Wormald, The Winchester Psalter (London, 1973). This book reproduces all the main decoration and prints or itemizes all the textual contents.

- Mara R. Witzling, 'An Archaeological Reconstruction of a Previous State of the Winchester Psalter', Gesta, XVII (1978), 29-31.

- Mara R. Witzling, 'The Winchester Psalter: A Re-ordering of Its Prefatory Miniatures According to the Scriptural Sequence', Gesta, XXIII (1984), 17-25.

Older works

- Edward Maunde Thompson, English illuminated manuscripts (London, 1895), pp. 29–33, pl. 9.

- G. F. Warner, Illuminated manuscripts in the British Museum (London, 1903), pl. 12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Winchester Psalter. |