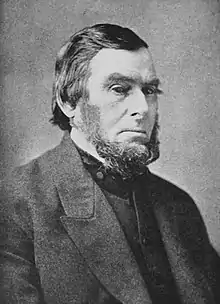

William H. Whitfield

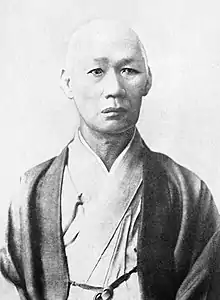

William H. Whitfield (Also known as Captain Whitfield) (November 11, 1804 – 14 February 1886) was an American sea captain and later a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Born in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, he is primarily remembered today for having rescued the 14-year-old Manjirō Nakahama from a shipwreck in 1841 and acting as his foster father until Manjirō could return to sea in 1847.[1]

William H. Whitfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 11, 1804 |

| Died | February 14, 1886 (aged 81) Fairhaven, Massachusetts |

| Occupation |

|

Life and career

Whitfield was born in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. His mother, Sybil Whitfield, was unmarried, and he was raised by his maternal grandmother, Parnel Whitfield. Like his uncle George (1789–1882), he became a whaling captain, starting his career in 1819 at the age of 15 when he signed on as a crewman on the Martha, a ship commanded by his uncle. He subsequently served as the boat steerer of the Pacific, second mate on the Missouri, and first officer of the William Thompson. In 1835 Whitfield married Ruth C. Irish of Fairhaven Connecticut. He then sailed for the Pacific as captain of the Newark. During that voyage he learned that Ruth had died in May 1837. Devastated by his wife's death, Whitfield went into a year of seclusion on his return to Fairhaven in 1838.[2][3]

In 1839 Whitfield became engaged to Albertina Keith of Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Shortly thereafter he set sail once again for the seas of Japan as the captain of the whaler John Howland. On June 27, 1841 the ship encountered five Japanese fishermen who had been cast away on the small uninhabited island of Tori-shima, one of whom was the 14-year-old Manjirō Nakahama. Whitfield took them aboard. Manjirō acted as his cabin boy and quickly began to learn basic English. When the whaling season ended, the John Howland sailed into Honolulu in October 1841. Manjirō's four friends found employment there, but he begged to remain with Whitfield and continue on the voyage back to Fairhaven. Whitfield had also grown attached to the boy and regarded him as a foster son. The John Howland arrived back in Fairhaven in May 1843. Manjiro spent his first night in America at the Whitfield family house on Cherry Street. Shortly thereafter Whitfield left for his uncle George's home in Scipio, New York where he and Albertina were married on May 31, 1843. In the interim he arranged for Manjirō to board with the family of his friend Eben Akin and asked Jane Allen, a local teacher, to tutor Manjiro in preparation for formal schooling in the autumn.[2]

After William and Albertina's marriage, Manjirō lived with them as a member of the family, first in their house on Cherry Street in Fairhaven and then at their farm at nearby Sconticut Neck. Whitfield set sail again in 1844 as captain of the William and Eliza. It was during this voyage that his two-year-old son William Henry died in 1846 at the Sconticut Neck farm. Whitfield and Albertina had three more children: Marcellus Post (1849–1926), Sibyl Martha (1851–1894) and Albertina Pratt (1853–1876). Whitfield made several more voyages captaining the Gladiator, the Hibernia, and his own brig before retiring from the sea. In his later years, he became active in local politics, serving as a selectman of Fairhaven from 1871 to 1873 and as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1872 to 1873.[2][3]

Whitfield died on February 14, 1886 at his house on 11 Cherry Street in Fairhaven at the age of 81. Albertina died four years later. They are buried in the town's Riverside Cemetery as are all four of their children and Whitfield's first wife Ruth.[3][2]

Legacy

Manjirō Nakahama left Fairhaven to return to Japan in 1847 but he never forgot the kindness of Whitfield and the people of Fairhaven. In Japan his English skills and the education he had received led to his appointment as a samurai in the service of the Tokugawa Shogunate. In 1860 he wrote a lengthy letter to Whitfield in English recounting his life after he left Fairhaven. It began:

My Honored friend—I am very happy to say that i had an opportunity to say to you a few lines. I am still living and hope you were the same blessing. i wish to meet you in this world once more. How happy we would be. Give my best respect to Mrs. and Miss Amelia Whitfield,[lower-alpha 1] i long to see them. Capt. you must not send your boys to the whaling business; you must send them to Japan. I will take care of him or them if you will. Let me know before send and I will make the arrangement for it.[1]

In 1870 Manjirō was a member of a Japanese government commission sent to Europe to study military science during the Franco-Prussian War. Afterwards he went to the United States, was formally received in Washington, and then made his way by train to Fairhaven where he spent the night with Whitfield and his family at their farm in Sconticut Neck.[4] Twenty years after his death, Nakahama's eldest son gifted a 14th-century samurai sword to the people of Fairhaven in gratitude for his father's rescue and the education he had received in the town. After a wreath-laying on Whitfield's grave, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States presented the sword in a ceremony on July 4, 1918.[1] Calvin Coolidge, at the time Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts, gave the welcoming address, concluding with:

This sword was once the emblem of place and caste and arbitrary rank. It has taken on a new significance because Captain Whitfield was true to the call of humanity, because a Japanese boy was true to his call of duty.[1][lower-alpha 2]

In 1987 Akihito, the future Emperor of Japan, visited Fairhaven and Whitfield's grave, and Japanese visitors to the town still stop by the grave to leave gifts in tribute to Whitfield.[5] A delegation from Fairhaven journeyed to Tosashimizu, Manjirō's native city, in December 1987 and signed a Sister City agreement between the two towns which in turn led to the establishment of the Whitfield-Manjiro Friendship Society. By 2007 Whitfield's old house on Cherry Street was in ruins and up for sale. On hearing this, Japanese members of the society began raising funds to buy and renovate it as a gift to Fairhaven. The house, now a museum dedicated to Manjirō Nakahama and his life in Fairhaven, was officially opened on May 7, 2009 in a ceremony attended by 100 of the Japanese donors, the Japanese Consul Generals to New York and Boston, and members of the 5th and 6th generations of both the Whitfield and Nakahama families.[6][7]

Notes

- Amelia Whitfield (1791–1869) was William Whitfield's aunt. She also lived in the Whitfield house on Cherry Street and on the Sconticut Neck farm until her marriage in 1857.[2]

- The sword was held in the Rogers Room of the Millicent Library where it was continuously displayed, even during World War II. It was stolen in 1977 and has never been recovered.[3]

References

- s.n. (1918). The presentation of a Samurai sword, the gift of Doctor Toichiro Nakahama, of Tokio, Japan, to the town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, pp. 9–11. Millicent Library

- Bernard, Donald R. (1992). The Life and Times of John Manjiro, pp. 1–2; 41; 50; 214. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070049475

- Fairhaven Massachusetts Office of Tourism (2017). Fairhaven Visitors' Guide, pp. 12–13; 26.

- Kawada, Ikaku and Manjirō Nakahama (English translation and notes by Junya Nagakuni, Junji Kitadai, and Stuart M. Frank) (2003). Drifting Toward the Southeast: The Story of Five Japanese Castaways, a Complete Translation of Hyoson Kiryaku (a Brief Account of Drifting Toward the Southeast) as Told to the Court of Lord Yamauchi of Tosa in 1852 by John Manjiro, p. 12. Spinner Publications. ISBN 0932027563

- Weisberg, Tim (2010). Ghosts of the South Coast, pp. 35–36 (electronic edition). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 1614230099

- Whitfield-Manjiro Friendship Society (2016)."The Manjiro Story". Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- JapanInfo, Vol. 22 (May 2009). "The Capt. Whitfield - Manjiro Friendship Memorial House Opens in Massachusetts". Consulate-General of Japan in New York. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

Further reading

- Benfey, Christopher (2003). "Floating World", Chapter 1 of The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics, and the Opening of Old Japan. Random House. ISBN 0375503277. Excerpt published in The New York Times retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Urbon, Steve (3 May 2015). "Manjiro and Whitfield in the same photo? It may be a first". The Standard-Times. Retrieved via SouthCoastToday.com 12 February 2018.