William Byrd II

William Byrd II (March 28, 1674 – August 26, 1744) was an American planter and author from Charles City County in colonial Virginia. He is considered the founder of Richmond, Virginia.

William Byrd II | |

|---|---|

Colonial Virginia planter at 50 | |

| Born | March 28, 1674 |

| Died | August 26, 1744 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Felsted School (classical) Middle Temple (law) |

| Occupation | Planter, statesman, and author |

| Known for | Founder of the City of Richmond |

| Title | Colonel |

| Spouse(s) | Lucy Parke (m. 1706–1715; her death) Maria Taylor (m. 1724) |

| Children | Evelyn, Wilhelmina, Anna Jo, Maria, Jane, William Byrd III |

| Parent(s) | William Byrd I Mary Horsmanden |

Byrd's life showed aspects of both British colonial gentry and an emerging American identity. His education included the classics, apprenticeship with London global business agents, and legal studies. He was admitted to the bar and served for years as Virginia Colony's official agent in London where he opposed increasing the power of royal governors. A member of the Royal Society, he was an early advocate of smallpox inoculation.[1] Byrd treated the enslaved people in his household appallingly and was a renowned philanderer.[2] His exploits are captured in his diary, which is notable for its openness on matters of sex.[2]

Upon his return to Virginia, Byrd expanded his plantation holdings, was elected to the House of Burgesses, and served on Virginia Governor's Council, also known as Virginia's Council of State (the Upper House of the colonial legislature), from 1709 until his death in 1744. He commanded county militias and led surveying expeditions along the Virginia-Carolina border and the Northern Neck. His enterprises included promoting Swiss settlement in mountainous southwest Virginia and iron mining ventures in Germanna and Fredericksburg.[3]

Biography

William Byrd II was born in Henrico County, Colony of Virginia. His father, Colonel William Byrd I, had come from England to settle in Virginia.

When he was seven years old, his father sent him to London for schooling. He was educated at Felsted School in Essex, England, for the law. While there, Byrd became engrained in London's society and politics. Not only did he study law, but in 1696, at age 22, he was also elected by friends in the aristocracy as a Fellow in the Royal Society. He also served as a representative of Virginia in London. He was a member of the King's Counsel for 37 years. Byrd returned to Richmond upon the death of his father in 1705. He had a very large inheritance, and was now required to run the estate. He returned to the Colony following his schooling and lived in lordly estate on Westover Plantation.

Upon Byrd's return to Virginia in 1705, he found that the colonies lacked the social vibrancy that he had found in England. Therefore, he began his search for a wife; his goal was not only to find companionship, but to increase his wealth. Lucy Parke (age 18) was an obvious candidate for his affections. Not only was she beautiful and wealthy; but her father, Colonel Daniel Parke II, was the governor of the Leeward Islands.

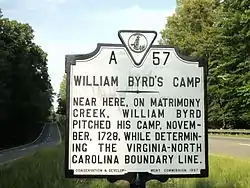

Byrd became very ambitious after his father's death and sought the governorship of Virginia. When he was denied the position, William Byrd II returned once more to London on romantic endeavors. He was not only rejected by the elite women but also by the British government. While Byrd considered himself an Englishman, the fact that he was born in the American colonies kept other true Englishmen from considering him as such. Parliament sent Byrd back to Virginia, where he finally accepted his role as a mere Virginia delegate. However, he was chosen to commission the survey of the Virginia–North Carolina border.

Lucy died of smallpox in 1715, and Byrd remarried Maria Taylor eight years later.

William Byrd II died on August 26, 1744, and was buried at Westover Plantation in Charles City County.[4]

Byrd's son, William Byrd III, inherited the family land but chose to fight in the French and Indian War rather than spend much time in Richmond. After he squandered the Byrd fortune, William Byrd III parceled up the family estate and sold lots of 100 acres (0.40 km2), in 1768.

Marriages

.jpg.webp)

Upon Byrd's return to Virginia in 1705, he found that the colonies lacked the social vibrancy that he had found in England. He began his search for a wife, both for companionship and to increase his wealth. He found a solid candidate in Lucy Parke: beautiful, wealthy, and the daughter of Colonel Daniel Parke II, Governor of the Leeward Islands.

At the time, Lucy Parke was 18 years old, and her mother was concerned that Daniel Parke's many romantic affairs and reputation for stinginess were hurting his daughter's marriage prospects. When Byrd wrote a letter to the Parkes asking to court Lucy, they immediately accepted. Byrd wooed her with passionate letters proclaiming his love, e.g., "Fidelia, possess[ed] the empire of my heart" (Treckel 133). The two were soon wed.

Soon after their wedding, Parke found that her husband was not open to emotional and intellectual closeness. Byrd was far more interested in sexual intimacy alone, and like his father-in-law, Byrd was sexually unfaithful to his wife. Parke often turned a blind eye to such affairs, but showed her displeasure if this was mentioned publicly or she caught him in the act. Byrd notes in his diary entry for July 15th 1710 that Parke caught him in flagrante with an enslaved maid, Jenny, who was likely a minor. Parke, ‘against my will caused little Jenny to be burned with a hot iron, for which I quarrelled with her’.[5] On March 2nd 1712, Byrd again recorded in his diary a 'Terrible quarrel with my wife concerning Jenny… she was beating her with the tongs. She lifted up her hands to strike me but forbore to do it. She gave me abundance of bad words and endeavoured to strangle herself… I believe in jest only.’

Parke and Byrd quarrelled over other matters, particularly the running of the household. Byrd wanted patriarchal control, while Parke wanted her own say too. They disagreed on whose power reigned over the various parts of the estate, and their arguments were often heated. Parke refused to conform to the traditional role of the submissive wife and wished to assert her authority over enslaved people in their household. The incident with Jenny is a classic example of this. Byrd often rebuked her in front of others when she acted upon this inclination, undermining her authority.

Byrd insisted on required absolute sovereignty over the library. To him, it was a very intimate and personal place, one in which Parke did not belong. He disliked her entering the library at all, and he loathed her tendency to borrow books when he was away.

The biggest arguments the couple had were over money. Parke had a taste for fine fabrics and for imported household items. Byrd found her purchases to be frivolous and often had her sell brand-new items. It is likely that Parke hoped to be able to spend more of her husband's money, having grown up with a stingy father.

Despite the couple's differences, aspects of their relationship appear tender and romantic. Following Byrd to London, she died of smallpox in 1716. Byrd suffered greatly, blaming himself for her death. He wrote of the ‘insupportable pain in her head… the smallpox… we thought it best to tell her the danger. She received the news without the least fright, and was persuaded she would live… Gracious God what pains did she take to make a voyage hither to seek a grave.’[6] Byrd had made the voyage to try and rescue his position with the Board of Trade and the Governor of Virginia, and now he linked this ambition to his young wife's early death.

Byrd remarried Maria Taylor (1698-1771) eight years later. Taylor was the heiress of a wealthy family from Kensington, and an altogether different character to Parke. Her rare appearance in Byrd's diary has left some historians with the image of a more submissive wife, accepting Byrd's authority over the household. She was certainly well-mannered, and epitomised the upper-class lady that he desired, without any record of passionate "flourishes" to quell arguments or threatening the servants. Despite Byrd's renewed sexual advances on other women, Taylor kept the household in good order. More recently, Allison Luthern has suggested that 'a closer examination of sources reveals that Maria [Taylor] Byrd was not as easily governed by these powerful men as William Byrd II... indicates.'[7] Taylor appears to have tactically bided her time as Byrd aged, controlling the education of their children together and preparing to take control of Westover in her widowhood. She outlived Byrd by 37 years, supported by an annual pension in Byrd's will for £200 on the condition that she remain unmarried and living in Westover.[8]

Personal diaries

The first diary runs from 1709 to 1712 and was first published in the 1940s. It was originally written in a shorthand code and deals mostly with the day-to-day aspects of Byrd's life, many of the entries containing the same formulaic phrases. A typical entry read like this:

[October] 6. I rose at 6 o'clock and said my prayers and ate milk for breakfast. Then I proceeded to Williamsburg, where I found all well. I went to the capitol where I sent for the wench to clean my room and when I came I kissed her and felt her, for which God forgive me ... About 10 o'clock I went to my lodgings. I had good health but wicked thoughts, God forgive me.

A man of great passion who was forever making vows of repentance and then promptly breaking them, Byrd was not uncomfortable with the contradictions in himself. Though his diary recounts his many romantic exploits (including those with his own wife) he never shows much more than the most cursory remorse for his less savory actions.

In addition to the passages recounting his many infidelities, the diary also contains a record of the lives of enslaved people held by Byrd and his subsequent punishment. Byrd often beat the enslaved people he held and sometimes devised other punishments even more cruel and unusual:

September 3, 1709: I ate roast chicken for dinner. In the afternoon I beat Jenny for throwing water on the couch.

December 1, 1709: Eugene was whipped again for pissing in bed and Jenny for concealing it.

December 3, 1709: Eugene pissed abed again for which I made him drink a pint of piss.[9]

Byrd often quarreled with his wife over the treatment of the people they held in slavery. These disagreements did not bode well for the people in question:

[1712 May] 22 ... My wife caused Prue to be whipped violently notwithstanding I desired not, which provoked me to have Anaka whipped likewise who had deserved it much more ...

Byrd was, for a time, receiver general of Virginia and owned the large plantation (and large debts) his father left him upon his death. In 1709, the year he began his secret diary, he was appointed to the Council of Virginia, which meant that he spent much of his time in London. Many of the entries in his diary deal with affairs of state and the running of a plantation, as well as his ongoing education. He was a man of great learning, and most entries record which Greek or Hebrew text he read that morning (or gives the reason for which he was unable to read), and he was known for his extensive private library. He also mentions in nearly every entry having "danced my dance", meaning he performed his calisthenic exercises.

Literary pursuits

While William Byrd was an avid planter, politician, and statesman, he was also a man of letters. All but two of his early literary works remained in manuscript form after his death at Westover in 1744, only appearing in print in the early 19th century and later receiving "dismissive commentary" by literary critics. It was not until the last quarter of the 20th century that his writings were assessed with any critical enthusiasm.[10]

Of Byrd's reassessed literary collection, the most frequently discussed are a pair of texts, published in 1841, The History of the Dividing Line betwixt Virginia and North Carolina, Run in the Year of Our Lord 1728 and The Secret History of the Line, a second edition, with pseudonymous names replacing the real names in the first version. They both provide a colonial perspective on the mapping of the border between Virginia and North Carolina. Among other works published from The Westover Manuscripts in 1841, are A Journey to the Land of Eden, A Progress to the Mines, and The Secret Diaries of William Byrd of Westover.

The History of the Dividing Line is Byrd's most influential piece of literary work and is now featured regularly in textbooks of American Colonial literature.[11] Through The Secret History, the societal stereotypes and attitudes of the time are revealed. According to Pierre Marambaud, Byrd "had first prepared a narrative, The Secret History of the Line, which under fictitious names described the persons of the surveying expedition and the incidents that had befallen them." (Marambaud 144).

In The History of the Dividing Line and The Secret History, Byrd incorporates the motifs of slothfulness and sexual desire. He focuses on the work ethic in The History of the Dividing Line and emphasizes the sheer laziness of the North Carolinians. Byrd defines the border between Virginia and North Carolina as a cultural border as well as a physical one. He describes the residents of North Carolina as corrupt and portrays himself in contrast to their characters. He describes the ways in which the North Carolina men chase after women, as well as the ready acquiescence of the women to the men's urges. He also explains the methods in which he brought control to the sexual situations into which the other men got themselves. For example, Byrd informs the reader that, having encountered a beautiful woman, "Shoebrush [John Lovick] was smitten at the first glance and examined all her neat proportions with a critical exactness. She struggled just enough to make her admirer more eager, so that if I had not been there, he would have been in danger of carrying his joke a little too far." (p. 642, Heath) This is one of many examples in which Byrd clearly indicates that he was the moral superior of his companions.

It is also likely that Byrd was using these writings as a method of promoting himself politically. In showing himself to be the sole person in the stories who is morally upstanding, focused, and responsible, he is describing himself as a great leader. In representing the Carolinians on his commission as morally reprehensible, lazy, lawless people, he is implying that—as he can lead such a difficult group of people, he is clearly capable of leading other, less savage people.

Legacy

Byrd gathered the most valuable library in the Virginia Colony, numbering some 4,000 books. He was the founder of Richmond and provided the land where the city was laid out in 1737. He was the author of the Westover Manuscripts and most prominently, The Secret Diaries of William Byrd of Westover. His writings have been published in later editions.

Several places are named after the William Byrd II:

- Byrd Park in Richmond and the William Byrd Community House were both named for William Byrd II.

- William Byrd High School in Vinton, Virginia, was also named after William Byrd II. Byrd surveyed parts of the Roanoke Valley, and the school's mascot is a Staffordshire Bull Terrier. It is said that Byrd owned two of these dogs.

Byrd had notable descendants in the 20th century:

- naval officer, pioneering aviator, and explorer Richard Evelyn Byrd, after whom Richard Evelyn Byrd Flying Field (now Richmond International Airport) was named.

- Virginia Governor and U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd.

- U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd Jr., also of Virginia.

Bibliography

The Westover Manuscripts (1841), comprising:

- The History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina

- Diaries Edited By Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling-The Dietz Press-Richmond, VA 1941

References

- Encyclopedia Virginia, Byrd (1674–1744). Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, Charlottesville, Virginia. Colonial History editor, John Kolp, instructor of U.S. History at Augustana College, Illinois, and former professor of history, U.S. Naval Academy. Viewed April 6, 2012.

- Malcolmson, Cristina (December 4, 2018). ""The Fairest Lady": Gender and Race in William Byrd's "Account of a Negro-Boy that is dappel'd in several Places of his Body with White Spots" (1697)". Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies. 18 (1): 159–179. doi:10.1353/jem.2018.0006. ISSN 1553-3786. S2CID 166096874.

- Encyclopedia Virginia, "William Byrd (1674–1744)". Viewed April 6, 2012.

- William Byrd II

- Lockridge, Kenneth A. (1987). The Diary, and Life of William Byrd II of Virginia, 1674-1744. London. p. 66-68.

- Lockridge, Kenneth A. (1987). The Diary, and Life of William Byrd II of Virginia, 1674-1744. London. p. 83.

- Luthern, Allison (2012). "The Truth of it Is, She Has Her Reasons for Procreating So Fast": Maria Taylor Byrd's Challenges to Patriarchy in Eighteenth-century Virginia (Thesis, Doctoral dissertation). Appalachian state University. p. 2.

- Luthern, Allison (2012). "The Truth of it Is, She Has Her Reasons for Procreating So Fast": Maria Taylor Byrd's Challenges to Patriarchy in Eighteenth-century Virginia (Thesis, Doctoral dissertation). Appalachian state University. p. 49.

- Byrd, William; Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling, eds. "William Byrd's diary". Africans in America. PBS.org. Retrieved September 15, 2008.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Byrd, William.The Dividing Line Histories of William Byrd II of Westover. Kevin Joel Berland, ed. The University of North Carolina Press. 2013. p27

- Encyclopedia Virginia, Byrd (1674–1744). Accessed: 28 Aug 2014.

Sources

- Byrd II, William (2009). "The History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina; The Secret History of the Line". In Paul Lauter; Richard Yarborough; John Alberti; Mary Pat Brady; Jackson Bryer (eds.). The Heath Anthology of American Literature: Volume A : Beginnings to 1800 (6 ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Company, 2009. pp. 636–54. ISBN 978-0-618-89799-5.

- Byrd II, William (1929). Histories of the Dividing Line betwixt Virginia and North Carolina. Raleigh, North Carolina: N.C. Historical Commission.

- Marambaud, Pierre (April 1970). "William Byrd of Westover: Cavalier, Diarist, and Chronicler". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Virginia Historical Society. 78 (2): 144–183. JSTOR 4247559.

- Treckel, Paula A (Spring 1997). ""The Empire of My Heart": The Marriage of William Byrd II and Lucy Parke Byrd". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Virginia Historical Society. 105 (2): 125–156. JSTOR 4249635.

- Byrd, William (1941). The secret diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709-1712. The Dietz Press, 622 pages., Book

Further reading

- Harrison, Mrs. Burton (June 1891). "Colonel William Byrd of Westover, Virginia". The Century; A Popular Quarterly. The Century Company. 42 (2): 163–179. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- Katheder, Thomas, "Provenance of William Byrd's Copy of Britannia Illustrata: Byrd's London Bookseller Identified" (August 29, 2011). (Discussion of Byrd's private library and discovery of one of his principal London booksellers.) [Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1919240]

External links

- Biography at Virtualology.com (under his father)

- William Byrd II (Encyclopedia Virginia) Encyclopedia Virginia: William Byrd (1674–1744)

- William Byrd (2) in The Literary Encyclopedia, The Literary Dictionary Company Limited

- William Byrd II at Find a Grave