William Alley

William Alley (also Alleyn and Alleigh; 1510 – 15 April 1570) was an Anglican prelate who was the Bishop of Exeter during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

Alley is known to the literary world by his Poor Man's Librarie, printed in folio by John Day, London, 1565, or Lectures upon the First Epistle of Saint Peter, red publiquely in the Cathedrall Church of Saint Paule, within the Citye of London, in 1560. Here are adioyned at the ende of euery special treatise, certain fruitful annotacions called miscellanea, because they do entreate of diverse and sundry matters.

Life

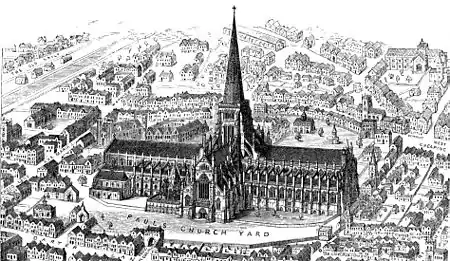

William Alley was a native of Wycombe, Bucks. He was educated at Eton College and finished his studies at the universities of Cambridge and Oxford. While a prebendary of St Paul's Cathedral, London, he was fixed on by Queen Elizabeth to succeed the deprived James Turberville. On 27 April 1560, she issued her congé d'élire to the Dean and Chapter. It was delivered to the president, Chancellor Levison, on 5 May. In the absence of the newly elected dean, Gregory Dodds, the election took place on 20 May and his consecration to the episcopate was held on 14 July that year.[1]

_300px.jpg.webp)

The revenues of the see and of his chapter had of late been lamentably reduced. But the rectory of Honiton was given to the bishop towards the better maintenance of his rank; and in its parochial church, and even in the rectory-house, he held several ordinations "in Rectoria - in domo Domini Episcopi apud Honyton", as we learn from his registers. Owing to the impoverished state of the finances of his dean and chapter, with the unanimous consent of its members, and under the royal authority, he diminished the number of the canons of the cathedral from twenty-four to nine. His statute for this purpose is dated 22 February 1561. Attempts were made at subsequent periods to set aside this ordinance, which conferred the power and emoluments on the favoured nine, to the exclusion of the other fifteen. It proved useless, however, to combat a practice which had been legalised by time and authority.

Richard Hooker, who knew the bishop well, commends his affability of manners, regularity of life, and singular learning. He added that,

"his library was replenished with all the best sort of writers, which most gladly he would impart, and make open to every good scholar and student, whose company and conference he did most desire and embrace."

Later, however, in his History,[2] in describing the Mayor, Robert Midwynter, Hooker says that,

"in office he showed himself, as he was, an upright justice, and governed the city in very good order. In nothing was he more stowte, than he was against Bishop Alley, when he brought a commyssion to be a Justice of the Peace within the citie, contrary to the lybertes of the same."

After governing the diocese for about nine and a half years, he died, according to his epitaph, on 15 April 1570, aged 60, and was buried in the choir of his cathedral.

References

| Wikisource has the text of the 1885–1900 Dictionary of National Biography's article about William Alley. |

- Matthew Parker's Register fol. 80.

- p. 359

- George Oliver. Lives of the Bishops of Exeter Broadgate, England: William Roberts, 1861.

Attribution

This article contains text from Lives of the Bishops of Exeter, a work in the public domain.

| Church of England titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James Turberville |

Bishop of Exeter 1560–1571 |

Succeeded by William Bradbridge |