Universalism and the Latter Day Saint movement

Christian universalism was a theology prevalent in the early United States coinciding with the founding of the Latter Day Saint movement (also known as Mormonism) in 1830. Universalists believed that God would save all of humanity. Universalism peaked in popularity during the 1820s and 1830s, and the idea of universal salvation for all humanity was hotly debated. Several revelations of the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, Joseph Smith, dealt with issues regarding Universalism, and it was a prominent heresy in the Book of Mormon. Smith's father was a Universalist, while his mother was a traditional Calvinist, creating strain in the Smith family home.

The Book of Mormon is generally seen as containing anti-Universalist rhetoric of the 1820s, supporting the idea that Hell is real and a place where the wicked will suffer for eternity. The extent that the debates over Universalism from the 1820s influenced the Book of Mormon is controversial for Latter Day Saints, as many believe the book to be of ancient origin. Later revelations were seen by early members and outsiders as supporting a more universalist approach, where the wicked are still redeemed in heaven. This view on salvation led many to leave the early church.

Background

Universalism in the Early United States

The distinguishing doctrine of Universalism was that God would save all of humanity regardless of their righteousness or wickedness. To a Universalist, eternal damnation was an excessive and unjust punishment that far outweighed any sin a person could commit, and antithetical to a merciful God.[2]Prominent Universalist advocate Hosea Ballou summarized the motivation for the doctrine with the rhetorical question:

Your child has fallen into the mire, and its body and its garments are defiled. You cleanse it, and array it in clean robes. The query is, Do you love your child because you have washed it? Or, Did you wash it because you loved it?[3]

Universalists were divided on the extent of the punishment of the sinner:

Restorationists

- Believed sinners would be temporarily punished after death before eventually being saved.

Ultra-Universalists or Modern Universalists

Universalism was brought to the North American colonies in the early 18th century by the English-born physician George de Benneville and made popular by John Murray, Elhanan Winchester, and Hosea Ballou. It reached its apex of popularity in 1833, becoming one of the fourth or fifth largest denominations in the United States.[3][5] Debates over Universalism were ubiquitous in the American theological landscape.[6] It was seen as a threat by the orthodox, Calvinist Congregationalists of New England such as Jonathan Edwards, who wrote prolifically against universalist teachings and preachers.[7] While the mainline Protestant denominations (e.g. Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Methodists, Baptists, and Episcopalians) frequently disagreed among themselves, they were united in their belief that Universalism was a heresy, and are generally referred to today as the orthodox viewpoint, or anti-Universalists.[4]

Universalism and early Latter Day Saints

In 1823 there were around 90 Universalist congregations in the greater Finger Lakes area where Mormonism was founded. In 1818, speaking of a town 15 miles south of the Joseph Smith family home, minister David Millard said, "Universalism was a predominant opinion in the place."[8] Universalism was also a prominent theology in the Joseph Smith's home growing up.[3] His father, Joseph Smith Sr., along with his Uncle Jesse and Grandfather Aesel founded a Universalist Society in Topsfield, Massachusetts, in 1797. Topsfield was just 15 miles north of the residence of influential Universalist John Murray.[9]

Joseph Smith Sr. continued his belief in Universalism into adulthood, for which he was criticized by some of his neighbors.[3] Joseph Smith Sr.'s belief in Universalism contributed to his and some of his children's disdain for revival churches in the 1820s.[10] In 1823, when Smith's older brother Alvin died, the reverend who preached at the funeral implied that Alvin had gone to Hell since he had never been baptized, which angered Smith's father. Joseph Smith's mother, Lucy Mack Smith, was an orthodox Presbyterian, and this differing belief system created tension in the Smith family home. Some of their children followed after their Mother and were baptized into Presbyterianism, while others followed their Father and did not become baptized, including Joseph Smith Jr. Joseph Smith's grandfather Asael Smith remained unmoved in his Universalist convictions upon hearing of Mormonism, but according to family tradition he did eventually renounce Universalism on his deathbed in November 1830.[11] Joseph Smith Sr. also changed his mind about the necessity of baptism, and was baptized on April 6, 1830, upon which Joseph Smith Jr. became overwhelmed, declaring, "Oh! My God I have lived to see my own father baptized into the true church of Jesus Christ!"[12]

Lucy's father Solomon Mack converted from Universalism to orthodox Christianity in the early 1800s and back to Universalism in 1818.[10] One of the scribes of the Book of Mormon, Martin Harris, was also a Universalist at one point before joining the Latter Day Saint movement. Joseph Knight Sr. and members of his family had also been Universalist.[13]

Universalism and the Book of Mormon

A central theme of the Book of Mormon is the salvation of humanity. The Book of Mormon rejects the doctrine of universal salvation as heretical.[14][15] The discussions surrounding Universalism in the Book of Mormon are similar to those in early nineteenth century United States.[16] Early converts may have felt their anti-Universalist views confirmed by the Book of Mormon.[17]

The anti-Universalism of the Book of Mormon was recognized by its early readers, both adherents and critics. Prominent opponent Alexander Campbell wrote, "This prophet Smith ... wrote ... in his book of Mormon, every error and almost every truth discussed in N. York for the last ten years. He decides all the great controversies" and included "eternal punishment" as one of those controversies.[4][18] Early Latter Day Saint Sylvester Smith wrote in 1833 that "the Universalist says it [the Book of Mormon] reproaches his creed."[19] Another early convert, Eli Gilbert, of Connecticut said that the Book of Mormon shortly after publication, that it "bore hard upon my favorite notions of universal salvation" [20][8]

Amongst anti-Universalists there was general agreement that there was a two-outcome doctrine of heaven and hell, but differing opinions on who would ultimately be saved. Calvinism for example believed that an omniscient God already had decided who would be saved, and human actions on earth would do little to change things. The Book of Mormon generally aligned with Methodists of the time, who divided humankind into five groups of people:[4]

| Group of People | Methodist View | Book of Mormon View | Universalist View |

|---|---|---|---|

| Those dying in childhood | Eternal Life[21] | Eternal Life[22] | Eternal Life |

| Those with faith in Jesus during mortality | Eternal Life[23] | Eternal life [24] | Eternal Life |

| Those with no opportunity to know Jesus | Mixed views, from "no salvation" to "possible salvation for some."[25][4] |

Eternal Life[26] | Eternal Life[27] |

| Those who are taught Jesus but die in sin | Condemned to hell[28] | Condemned to hell[29] | Eternal Life |

| Those who deny the Holy Ghost | Condemned to hell[30] | Condemned to hell[31] | Eternal Life[32] |

Notably, the Book of Mormon sided with Universalists with regard to the salvation of those who never had a chance to hear of Jesus.[4]

Restorationists vs. Ultra-Universalists

Universalists disagreed on whether there would be torment after death before ultimate salvation. Restorationists believed there would be a time of suffering after death while Ultra-Universalists believed there was no suffering after death.

In the Book of Mormon, Nephi's older brothers also wonder if punishment will happen in this life, and ask him if hell is "the torment of the body in the days of probation, or doth it mean the final state of the soul after the death of the temporal body?" Nephi's answer sides thoroughly with the anti-Universalists, "There is a place prepared, yea, even that awful hell of which I have spoken, and the devil is the preparator of it; wherefore the final state of the souls of men is to dwell in the kingdom of God, or to be cast out because of that justice of which I have spoken."[33][4]

Eat, drink, and be merry

Because Universalists believed that all would be saved regardless of righteousness, they were often painted by anti-Universalists as leading to Epicureanism, reasoning that if a person believed God would forgive any sin, then any sin would be allowed. For example, minister John Devotion wrote in 1801,

If there is no future judgment, they are certainly excusable who say, 'Let us eat and drink, for to morrow we die'. To suppose the future judgment is not a final and unalterable determination of our future state, opens the door to all manner of licentiousness in this life. That the punishment of the wicked will not be eternal, is ... believed by some at this day, to the destruction of vital piety and the morals of them who receive it.[34][35][36]

The Book of Mormon prophet Nephi similarly wrote that when the Book of Mormon would be revealed to the world at a time when a heresy existed that God would justify sin and still save his people. Nephi condemned both the ultra-universalist and restorationist doctrine, writing:

| Look up eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we die in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Yea, and there shall be many which shall say: Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die; and it shall be well with us. And there shall also be many which shall say: Eat, drink, and be merry; nevertheless, fear God—he will justify in committing a little sin; yea, lie a little, take the advantage of one because of his words, dig a pit for thy neighbor; there is no harm in this; and do all these things, for tomorrow we die; and if it so be that we are guilty, God will beat us with a few stripes, and at last we shall be saved in the kingdom of God.[37][38]

The Book of Mormon scripture uses the lexicon and imagery of the New Testament Parable of the Faithful Servant. In the parable, a wicked servant begins to "eat, drink and be drunken" after his master's coming is delayed. When the master comes, the wicked servants are "beaten with many stripes", while those who ignorantly sinned are "beaten with few stripes".[39] The parable was used as a proof text for restorationist Universalists, arguing that God beating with many and few stripes implied an eventual end to punishment. For example, Universalist Elhanan Winchester wrote, "The very idea of many and few stripes, supposes limited punishments: for how can those stripes be said to be few, which shall continue [eternally] while God exists?"[40][41][8]

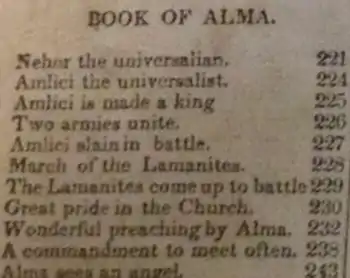

Nehor and Amlici

A common argument against Universalism was that it led to spiritual decay, greed, subversion and debauchery. The story of Nehor supported this idea.[6]

In the Book of Mormon, a man named Nehor created a movement that promotes universal salvation around 91 BCE.[42] Early Latter Day Saints explicitly tied the doctrine of Nehor to Universalism of the 1830s. The Book of Mormon says that he taught that "all mankind should be saved at the last day, and that they need not fear nor tremble, but that they might lift up their hands and rejoice; for the Lord had created all men, and had also redeemed all men; and, in the end, all men should have eternal life."[43] After losing a theological argument with a beloved orthodox prophet, Nehor became angry and killed the prophet. Nehor was condemned to death, but before he was hung from a hill, he "acknowledged between the heavens and the earth, that what he had taught to the people was contrary to the word of God; and there he suffered ignominious death".[44]

Nehor's doctrine of universal salvation became popular among a Book of Mormon ethnic group the Nephites, and the prophet Alma spent his ministry decrying the doctrine. Those ascribing to the "Order of the Nehors" were only kept from stealing, lying and killing because of the punishment of the law.[45]

Shortly afterwards in the narrative a man called Amlici who was after the Order of Nehor tried to become king, and led an army on the main body of Nephites. After being defeated, Mormon writes about the aftermath in anti-Universalist tones, "in one year were thousands and tens of thousands of souls sent to the eternal world, that they might reap their rewards according to their works, whether they were good or whether they were bad, to reap eternal happiness or eternal misery, according to the spirit which they listed to obey, whether it be a good spirit or a bad one"[46]

Ammonihah

In about 83 BCE, the prophet Alma went and preached in a city of Ammonihah, whose people followed the teachings of Nehor.[47] A lawyer named Zeezrom debates Alma and his friend Amulek using a Universalist line of questioning. Zeezrom asks Amulek, "Shall [the Son of God] save his people in their sins?" Amulek answers, "The Lord surely shall come to redeem his people; but he should not come to redeem them in their sins, but to redeem them from their sins." Zeezrom turns to the people and says, "[Amulek] saith that the Son of God shall come, but he shall not save his people-as though he had authority to command God." Amulek accuses Zeezrom of misrepresenting his words and clarifies, "I say unto you agin that he cannot save them in their sins; for I cannot deny his word, and he hath said that no unclean thing can inherit the kingdom of heaven; therefore, how can ye be saved, except ye inherit the kingdom of heaven? Therefore, ye cannot be saved in your sins." Alma and Amulek continue by expounding the doctrine that only those that believe and follow Jesus will be redeemed.[48][49]

Some Universalists in the 1800s used Matthew 1:21 to prove Universalism which reads, "And she shall bring forth a son, and thou shalt call his name JESUS: for he shall save his people from their sins.[50] Universalist Elhanan Winchester wrote about this passage in 1800, "all men are certainly the people of Jesus, ... consequently he shall save all mankind from their sins." Orthodox Anti-Universalists rejected Winchester's interpretation, including a preacher Charles Marford, who preached 10 miles from the Smith family home in Manchester New York who echoed a common rebuttal in 1819, "Christ is a Savior, to save his people from their sins, and not in them, and those that think otherwise will be overthrown."[8][51]

Alma uses a line of reasoning in his rebuke of Zeezrom's Universalism, "whosoever dieth in his sins, as to a temporal death, shall also die a spiritual death; yea, he shall die as to things pertaining unto righteousness. Then is the time when their torments shall be as a lake of fire and brimstone, whose flame ascendeth up forever and ever"[8][52]

This mirrors anti-Universalist rhetoric of the 1820s and 1830s. To establish that there was an actual place of punishment for sin after death, anti-Universalists would use John 8:21 as a proof text against Universalists which says, "I go my way, and ye shall seek me, and shall die in your sins: whither I go, ye cannot come"[8] and also the Book of Revelation, which discusses a "lake of fire and brimstone"[4]

Not fearing punishment for sin because of their Universalist beliefs, the people of Ammonihah burn alive the converts of Alma and Amulek. Alma and Amulek are imprisoned, and are asked by the leaders of Ammonihah, who are followers of Nehor, "After what ye have seen will ye preach again unto this people that they shall be cast into a lake of fire and brimstone?"[53] and "How shall we look when we are damned?"[54] Eventually Alma and Amulek were miraculously saved. The narrator Mormon writes that the people of Ammonihah did not repent but continued to be "of the profession of Nehor, and did not believe in the repentance of sins."[55] The city is eventually destroyed as prophesied by Alma.

Zoramites

In 74 BCE Alma and Amulek preached to a wicked group of people called the Zoramites. While the Book of Mormon does not label the Zoramites as Universalists, Alma and Amulek preach several sermons that used anti-Universalist arguments.

Atonement

The satisfaction theory of atonement was a medieval theological development, created to explain how God could be both merciful and just through an infinite atonement.[56] Ultra-Universalists felt an infinite atonement was unnecessary since sin itself is not infinite.[57] Orthodox religions condemned this way of thinking, "the necessity of an infinite atonement made by the death and suffering of Jesus Christ ... goes to overturn the whole system of the gospel."[8][58]

In Alma and Amulek's sermons they elucidate the satisfaction theory of atonement, saying, "There must be an atonement made, or else all mankind must unavoidably perish; ... therefore there can be nothing which is short of an infinite atonment which will suffice for the sins of the world. Therefore, it is expedient that there should be a great and last sacrifice; ... and that great and last sacrifice will be the Son of God, yea, infinite and eternal. And thus mercy can satisfy the demands of justice."[59]

Nature of human soul after death

Ultra-Universalists believed that sin and evil of the human soul did not extend after the death of the body.[60][4] Orthodox religions disputed this doctrine. Methodist Luther Lee for example wrote, "The scriptures teach that men will possess the same moral character in a future state, with which they leave this. ... If sin attached itself to the body only, it might be contended that it dies with the body; but having its seat in the soul, it will live with it when the body dies."[61] Amulek also condemns this doctrine, telling the Zoramites:

For after this day of life, which is given us to prepare for eternity, behold, if we do not improve our time while in this life, then cometh the night of darkness wherein there can be no labor performed ... for that same spirit which doth possess your bodies at the time that ye go out of this life, that same spirit will have power to possess your body in that eternal world. For behold, if ye have procrastinated the day of your repentance even until death, behold, ye have become subjected to the spirit of the devil, and he doth seal you his; therefore, the Spirit of the Lord hath withdrawn from you, and hath no place in you, and the devil hath all power over you; and this is the final state of the wicked.[62][4]

Corianton

Around 73 BCE Alma gave final lessons to his son Corianton. Corianton had come to believe in universal salvation, and justified himself in committing what Alma said was a serious sin. Alma urges Corianton, "my son, do not risk one more offense against your God upon those points of doctrine, which ye have hitherto risked to commit sin."[63]

Of particular concern to Corianton is "the justice of God in the punishment of the sinner ... that it is injustice that the sinner should be consigned to a state of misery."[64] This was a similar question that Universalists would ask to support universal salvation. Representative of this was the Universalist Magazine in 1818 which similarly asked, "How is it possible that a being of infinite goodness should design a rational creature of his own production for a state of endless misery?"[65]

Throughout Alma's talk with Corianton, he deconstructs Universalist claims. He teaches the Corianton about an infinite atonement that will save only the repentant, he corrects his sons false doctrine by teaching that this life is a "probationary time, a time to repent and serve God."[66] Alma says that contrary to universal salvation, after death "the spirits of those who are righteous are received into a state of happiness, which is called paradise ... the spirits of the wicked ... shall be cast out into outer darkness."[67] He tells Corianton that denying the Holy Ghost is an "unpardonable sin", and that "an awful death cometh upon the wicked ... for they are unclean, and no unclean thing can inherit the kingdom of God."[68]

This was in line with orthodox responses to Universalism. For example, Pastor John Cleaveland similarly argued against universal salvation in 1776, saying, "The time of life here on earth is our only probation time for eternity. ... after death, they that are filthy will be filthy still; and they that are holy will be holy still. While our bodies are in the grave our souls will be in a fixed state of happiness or misery, according to the state we were in when we gave up the ghost; if in Christ, of happiness; if out of Christ-of misery and after the resurrection and final judgment the wicked will be in a state of punishment in soul and body forever and ever."[69]

In a debate with a Universalist in 1832, Orson Hyde explicitly called Corianton a Universalist, and used Alma's lessons as arguments in the debate.[8][70]

Mormon

The Book of Mormon prophet Mormon discusses universal salvation in the Book of Helaman:

I would that all men might be saved. But we read that in the great and last day there are some who shall be cast out, yea, who shall be cast off from the presence of the Lord; Yea, who shall be consigned to a state of endless misery, fulfilling the words which say: They that have done good shall have everlasting life; and they that have done evil shall have everlasting damnation. And thus it is. Amen.[71]

Mormon later prophesied about heresies that would exist in the time the Book of Mormon would be translated, and included the doctrine of universal salvation saying, "There shall be many who will say, Do this, or do that, and it mattereth not, for the Lord will uphold such at the last day. But wo unto such, for they are in the gall of bitterness and in the bonds of iniquity."[72]

Viewpoints of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The existence of 19th century anti-Universalist arguments and rhetoric in the Book of Mormon has been pointed out as anachronistic by various scholars, including Fawn M. Brodie and Dan Vogel.[1] Most scholars of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) reject the anachronism.

LDS Church scholar Terryl Givens argues that because Book of Mormon prophets were shown by Jesus Christ the modern era, and the audience of the Book of Mormon was people in the modern era, that Book of Mormon prophets would have been intimately familiar with anti-Universalist rhetoric and purposefully used it to convince modern day readers. In Givens's view, the existence of anti-Universalist rhetoric validates ancient prophets prophetic abilities.[1] Similarly, LDS Church scholar Casey Paul Griffiths wrote, "If Mormon and Moroni saw our day, as they claimed, wouldn't we have expected them to write on topics related not only to us but to those of Joseph Smith's day? As one of the burning issues of the day, if the book did not deal with Universalism, it wouldn't be fulfilling its promises."[3]

Universalism and Joseph Smith revelations

In contrast to the Book of Mormon's anti-Universalist doctrine, later revelations by Smith took a more Universalist view of who would be saved.[4] Historian Richard Lyman Bushman wrote of the shift, "Contradictory as they sound, the universalist tendencies of the revelations and the anti-universalism of the Book of Mormon defined a middle ground where there were graded rewards in the afterlife, but few were damned."[73]

Revelation for Martin Harris

In the summer of 1829, within months after the Book of Mormon translation was complete, Joseph Smith received a revelation directed to Martin Harris, his early benefactor who had become hesitant about paying for the printing of the Book of Mormon.[74] Harris had been a believer in Universalism, and had apparently had questions about Universalist doctrine.[4]

In the debates between Universalists and anti-Universalists, the anti-Universalists would point to words like "eternal damnation" in the scriptures to argue that there was no end to suffering. Restorationist Universalists argued that such phrases did not actually mean never-ending, but were intended to scare humans into being righteous.[4][75]

The revelation to Smith enters the debate siding with the Restorationist Universalists. In it, the phrases "eternal damnation" and "endless torment" are used in the scriptures to "work upon the hearts of the children of men," and encourage humankind to be righteous through the threat of unending punishment. The revelation divulges a mystery it says are known to only a few, that the words "Eternal" and "Endless" are names for God, so when the scriptures use phrases like endless torment or eternal damnation, they do not refer to a period of time that does not end, but to "God's punishment". According to the revelation, Harris is commanded by God to "show not these things unto the world until it is wisdom in me. For they cannot bear meat now, but milk they must receive; wherefore they must not know these, lest they perish."[4][76]

Revelation to six Elders

In September 1830, Smith received a revelation for six elders in response to what was apparently a thoroughly Restorationist belief that had begun to be taught by some in the young Church.[4] The revelation makes clear that there will be suffering that does not end for some:

And the righteous shall be gathered on my bright hand unto eternal life; and the wicked on my left hand will I be ashamed to own before the Father; Wherefore I will say unto them—Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels. And now, behold, I say unto you, never at any time have I declared from mine own mouth that they should return, for where I am they cannot come, for they have no power.[77]

The Vision

On February 16, 1832, Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon announced they had received a revelation from God outlining the "important points touching the salvation of man." According to the revelation, all humanity will be saved in one of three degrees of glory, except for a small number who commit the unpardonable sin who will be banished to outer darkness. This revelation became known as "the Vision".[17]

Many converts to the early church disagreed with Universalism and felt the Book of Mormon justified their views. When news of "the Vision" reached the branches of the church, it was not well received by all and seen by many as a major shift in theology towards Universalism.[10] An antagonistic newspaper wrote that with "the Vision" Joseph Smith had tried to "disgrace Universalism by professing ... the salvation of all men."[78][17]

The branch in Geneseo, New York was particularly apprehensive. Ezra Landon, a leader of the Geneseo branch who had convinced a number of others against the Vision, told visiting missionaries that "the vision was of the Devil & he believed it no more than he believed the devil was crucified ... & that he Br Landing would not have the vision taught in the church for $1000." Joseph Smith sent a letter to the branch making clear that disbelief in the Vision was an excommunicable offense, and after refusing to change his position Landon was excommunicated.[17][79]

Brigham Young said,

It was a great trial to many, and some apostatized because God was not going to send to everlasting punishment heathens and infants, but had a place of salvation, in due time, for all, and would bless the honest and virtuous and truthful, whether they ever belonged to any church or not. It was a new doctrine to this generation, and many stumbled at it. ... My traditions were such, that when the Vision came first to me, it was directly contrary and opposed to my former education. I said, Wait a little. I did not reject it; but I could not understand it.[3][80]

Joseph Young, Brigham's brother, said, "I could not believe it at first. Why the Lord was going to save every body."[81][17]

"The Vision" was not published until five months after it was received, and after the first two years was rarely mentioned in the 1830s or early 1840s.[3] After the tepid reception of "the Vision", Joseph Smith gave instruction to missionaries to "remain silent" about it, until prospective converts had first believed the basic principles.[17][82]

Later views on Universalism

Starting around 1842 Joseph Smith and others appeared to be more open to being viewed as Universalist. Smith said in a speech in 1844, "I have no fear of hell fire, that doesn’t exist, but the torment and disappointment of the mind of man is as exquisite as a lake burning with fire and brimstone."[83][3]

Speaking of the resurrection, apostle Parley P. Pratt said, "This salvation being universal, I am a universalist in this respect,—this salvation being a universal restoration from the fall."[84]

In a sermon, Brigham Young read the contents of "the Vision" and then commented, "His plans are to gather up, and bring together, and save all the inhabitants of the earth, with the exception of those who have received the Holy Ghost, and sinned against it. With this exception, all the world besides shall be saved.—Is not this Universalism? It borders very close upon it."[85]

In 1980 LDS Church apostle Bruce R. McConkie used an anti-universalist argument when discussing what he said was a heresy that leads to Universalism: that progression was possible between the three different levels of heaven. Speaking of the heresy he said, "This belief lulls men into a state of carnal security. It causes them to say, 'God is so merciful; surely he will save us all eventually; if we do not gain the celestial kingdom now, eventually we will; so why worry?' It lets people live a life of sin here and now with the hope that they will be saved eventually."[6][86]

Researcher Brian D. Birch has called the LDS Church views on salvation "soft universalism", because although the vast majority will be saved, a few will not. Also, the LDS Church doctrine makes a distinction between salvation from sin, and exaltation, which is attaining the highest heaven and progressing eternally into godhood.[6]

See also

References

- Givens, T. (2002). By the hand of Mormon: The American scripture that launched a new world religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. page 164-166

- Vincent, Ken R. (January/February 2006). "Where Have All the Universalists Gone?". The Universalist Herald.

- Casey Paul Griffiths, “Universalism and the Revelations of Joseph Smith,” in The Doctrine and Covenants, Revelations in Context, ed. Andrew H. Hedges, J. Spencer Fluhman, and Alonzo L. Gaskill (Provo and Salt Lake City: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, and Deseret Book, 2008), 168–87.

- Clyde D. Ford "The Book of Mormon, the Early Nineteenth-Century Debates over Universalism, and the Development of the Novel Mormon Doctrines of Ultimate Rewards and Punishments" Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought , Spring 2014, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Spring 2014), pp. 1-23 University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/10.5406/dialjmormthou.47.1.0001

- Ann Lee Bressler, The Universalist Movement in America, 1770–1880 (New York: Oxford, 2001), 54.

- Brian D. Birch "A Portion of God's Light": Mormonism and Religious Pluralism Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought , Summer 2018, Vol. 51, No. 2 (Summer 2018), pp. 85-102 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/10.5406/dialjmormthou.51.2.0085

- Seymour, Charles. A Theodicy of Hell. Pp. 30–31. Springer (2000). ISBN 0-7923-6364-7.

- Metcalfe, B. L., & Vogel, D. (1993). New approaches to the Book of Mormon: Exploraton in critical methodology. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. chapter 2 online at:http://signaturebookslibrary.org/anti-universalist-rhetoric-in-the-book-of-mormon/ ; presented in lecture form at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wm7t7pNUWAM

- Richard Lloyd Anderson, Joseph Smith’s New England Heritage, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 136

- Brooke, J. L. (1996). The refiner's fire: The making of Mormon cosmology, 1644-1844. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. e-book location 1149, 1320, 2858 of 6221

- Bushman, R. L. (1988). Joseph Smith and the beginnings of Mormonism. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. page 28-29, 198

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2007). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York: Vintage Books. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4000-7753-3.

- Dan Vogel, ed., Early Mormon Documents, 3:29–30, 4:21, 110. (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1996)

- Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith:Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Knopf, 2005), 87-88

- Mark Thomas, "Revival Language in the Book of Mormon," Sunstone 8 (May-June 1983): 20.

- Hardy, G. (2010). Understanding the Book of Mormon: A reader's guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. e-book location 6811 of 8410

- McBride, M. S., & Goldberg, J. (2016). Revelations in context: The stories behind the sections of the Doctrine and Covenants: Including insights from the Joseph Smith papers. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. chapter "The Vision"

- Alexander Campbell, "The Mormonites," Millennial Harbinger 2 (January 1831): 93, as quoted in: RoseAnn Benson "Alexander Campbell and Joseph Smith Nineteenth-Century Restorationists" online at:https://rsc.byu.edu/alexander-campbell-joseph-smith/alexander-campbells-delusions-mormon-response

- Evening and Morning Star 2 [July 1833]: 108

- Messenger and Advocate 1 [Oct. 1834]: 9

- "With regard to infants. a.) The benefits of Christ's death are coextensive with the sin of Adam, (Rom. v,18;) hence all children dying in infancy partake of the free gift." Richard Watson "Theological Institutes: or, a View of the Evidences, Doctrines, Morals, and Institutions of Christianity (1823–1829)". Reprinted in 2 vols. (New York:Lane & Scott, 1850), 2:344–5 online at:https://archive.org/details/theologicalinsti00watsrich/page/n51/mode/2up

- "Little children also have eternal life." Mosiah 15:25"

- John Wesley, "A Farther Appeal to Men of Reason and Religion," in The Works of John Wesley, 14 vols. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1958), 8:68 online at:https://www.whdl.org/sites/default/files/publications/Wesley%20John%20-%20Farther%20Appeal%201745%20book.pdf

- "Look unto [Jesus], and endure to the end, and ye shall live; for unto him that endureth to the end will I give eternal life." 3 Nephi 15:9

- Methodist Luther Lee (1800–1883) wrote: "all who do not repent and obtain salvation, within the limits of this probationary state, must be forever lost." Methodist John Wesley was more open when he wrote, "nor do I conceive that any man living has a right to sentence all the heathen and Mahometan [sic] world to damnation." Methodist Richard Watson conceived that a minority of heathens who obeyed the law as they knew it could possibly be saved. see Ford page 7

- "They that have died ... in their ignorance, not having salvation declared unto them. And thus the Lord bringeth about the restoration of these; and they have a part in the first resurrection, or have eternal life, being redeemed by the Lord." Mosiah 15:24

- Universalist Paul Dean wrote, "The limitation of all means and methods of grace to the narrow span of this life . . . is opposed to reason and equity. ... Think what vast numbers of the heathen have lived and passed off the stage of life, without ever hearing so much as the name of Jesus. ... Shall we at once turn all these to destruction without even the possibility of escape? How much more reasonable is it for us to believe that Christ ... will continue to use with all his creatures, in all conditions, the most appropriate means for their reformation." Paul Dean, Course of Lectures in Defence of the Final Restoration (Boston: Edwin M. Stone, 1832), 51

- Timothy Merritt said that those who give in "to the will of the devil, are condemned by the law of God ... and heirs of everlasting punishment" Timothy Merritt, A Discussion on Universal Salvation in Three Lectures and Five Answers Against That Doctrine (New York: B. Wauch and T. Mason, 1832), 38.

- "Whosoever dieth in his sins, as to a temporal death, shall also die a spiritual death; yea, he shall die as to things pertaining unto righteousness. Then is the time when their torments shall be as a lake of fire and brimstone, whose flame ascendeth up forever and ever; and then is the time that they shall be chained down to an everlasting destruction, according to the power and captivity of Satan, he having subjected them according to his will. Then, I say unto you, they shall be as though there had been no redemption made; for they cannot be redeemed according to God’s justice;" Alma 12:16–18

- John Wesley said, "it is plain, if we have been guilty of this [unpardonable] sin, there is no room for mercy."John Wesley, "A Call to Backsliders," in The Works of John Wesley, 14 vols. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1958), 6:523. online at:https://archive.org/details/worksofrevjohnwe07wesl/page/52/mode/2up

- "If ye deny the Holy Ghost when it once has had place in you, and ye know that ye deny it, behold, this is a sin which is unpardonable;" Jacob 7:19; Alma 39:6

- Dan Vogel explained Universalist rationale:

"Universalists offered alternative interpretations of Jesus’s words about sinning against the Holy Ghost. For example, it was common for Universalists to argue that “this sin should not be forgiven, under the Jewish or Christian dispensation, as the word here translated world is used sometimes for an age: And this world may signify the Mosaic dispensation, and the world to come the Christian, and not the future state"

in "New Approaches to the Book of Mormon" Chapter 2. Hopkins, Samuel. An Inquiry Concerning the Future State of those who die in their Sins. Newport, RI: Solomon Southwick, 1783 page 76; see also Ballou, Hosea. A Treatise on Atonement. Randolph, UT: Sereno Wright, 1805. 167-68; - 1 Nephi 15:28–36

- John Devotion "The Substance of a Sermon Preached October 26, 1800" 1803

- John Cleaveland wrote of Universalism in 1776,

Follow this scheme but a little farther and you will deny a state of reward as well as punishment, and then join the issue with the atheistical and swinish Epicures, saying, Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.

John Cleaveland, "An Attempt to Nip in the Bud, the Unscriptural Doctrine of Universal Salvation (Salem, MA: E. Russell, 1776), 29 - Adam Empie wrote in 1825:

The ancient Epicureans, the lovers of pleasure and of the world-those whose maxim is, Let us eat, drink, and be merry ... upon the Universalist scheme, take the wisest course, and set the best example: for since we are sure of heaven and death, the most comfortable way of getting through life is the wisest and the best.

Adam Empie, "Remarks on the Distinguishing Doctrine of Modern Universalism" (New York: T. and J. Swords 1825), 33 online at: https://archive.org/details/remarksondisting00empi/page/18/mode/2up - 2 Nephi 28:7

- The phrase "eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die" is a conflation of 1 Kings 4:20, Eccl. 8:15, 1 Cor. 15:32/Isa. 22:13 and Luke 12:19. The complete phrase does not appear together in the Bible, but does appear together in literature of the 1820s (see Thomas Scott, The Holy Bible with Explanatory Notes (Boston: Samuel T. Armstrong, 1827), 3:612).

- Luke 12:42-48

- Elhanan Winchester, "The Works of Jesus: or, What he Did, and Taught, During his Abode on Earth" (London: Philadelphian Society, 1788), 45.

- Similarly, Preacher James Weaver wrote, "But if all sin is infinite, and requires infinite punishment, Why does God make a difference, by representing some sins to be beaten with many stripes, whilst others are beaten with only few stripes" James Weaver "Free Thoughts on the Universal Restoration of All Lapsed Intelligences from the Ruins of the Fall" (London: R. Hawes, 1792), 13

- Fenton, E. A., & Hickman, J. (2019). Americanist approaches to the Book of Mormon. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Alma 1:3–4

- Alma 1:15

- Alma 1:17–18

- Alma 3:26

- Alma 14:16–18, Alma 15:15

- Alma 11:34–37

- This story is recounted later on in the Book of Helaman 5:10–11

And remember also the words which Amulek spake unto Zeezrom, in the city of Ammonihah; for he said unto him that the Lord surely should come to redeem his people, but that he should not come to redeem them in their sins, but to redeem them from their sins. And he hath power given unto him from the Father to redeem them from their sins because of repentance; therefore he hath sent his angels to declare the tidings of the conditions of repentance, which bringeth unto the power of the Redeemer, unto the salvation of their souls."

- Matthew 1:21

- see also Charles Grandison Finney, Lectures on Revivals of Religion (6th ed.; New York: Leavitt, Lord and Company, 1835), 166. Hosea Ballou, A Treatise on Atonement (Randolph, VT: Sereno Wright, 1805), vii, 209.

- Alma 12:16–17 see also 2 Nephi 9:16, Mosiah 2:23 and Mosiah 15:26.

- Alma 14:14

- Alma 14:21

- Alma 15:15

- Blake T. Ostler, "The Book of Mormon as a Modern Expansion of an Ancient Source" Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought (Spring 1987): page 82 online at: https://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V20N01_68.pdf

- Influential Universalist Hosea Ballou typified the attitude, writing:

"The ideas, that sin is infinite, and that it deserves an infinite punisment; that the law transgressed is infinite, and inflicts an infinite penalty; and that the great Jehovah took on himself a natural body of flesh and blood, and actually suffered death on a cross, to satisfy his infinite justice, and thereby save his creatures from endless misery, are ideas which appear to me to be unfounded in the nature of reason, and unsupported by divine revelation.

Hosea Ballou, "A Treatise on Atonement" 2nd edition 1812. page iv online at: https://archive.org/details/atreatiseonaton04ballgoog/page/n5/mode/2up - Methodist Magazine (March 1825):82-85.

- Alma 34:9–16

- Hosea Ballou, “Lecture Sermon on Hebrews 2:14–15” in Lecture Sermons (Boston: Henry Bowen, 1818), 237.

- Luther Lee, Universalism Examined and Refuted (Watertown, N.Y.: Knowlton & Rice, 1836) 157–58.

- Alma 34:32–35

- Alma 41:9

- Alma 42:1

- Universalist Magazine (3 July 1818):2

- Alma 42:4

- Alma 40:12–13, also Matthew 8:12, 13:42, 13:50, 22:13, 25:30

- Alma 40:26, compare to Revelation 22:11 and Ephesians 5:5

- John Cleaveland, "An Attempt to Nip in the Bud, the Unscriptural Doctrine of Universal Salvation" (Salem, MA: E. Russell, 1776), iv.

- Hyde, Journal, 4 Feb. 1832; cf. Alma 41:3-4

- Helaman 12:25–26

- Mormon 8:31.

- Bushman, R. L., & Woodworth, J. (2007). Joseph Smith: Rough stone rolling. New York, NY: Vintage Books.e-book location 4457

- D&C 19, Book of Commandments 16.

- Paul Dean, Course of Lectures in Defence of the Final Restoration (Boston: Edwin M. Stone, 1832), 65-66

- D&C 19:21–22

- D&C 29:27–29

- "Changes of Mormonism," Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate, vol. 3, no. 11 (Mar. 17, 1832)

- "Letter to Church Leaders in Geneseo, New York, 23 November 1833," p. [2], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed August 24, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-to-church-leaders-in-geneseo-new-york-23-november-1833/2

- Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1874–86), 16:42.

- Joseph Young, "Discourse," Deseret News (Mar. 18, 1857), 11.

- "History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838]," p. 762, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed August 8, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-b-1-1-september-1834-2-november-1838/216

- Stan Larson, “The King Follett Discourse: A Newly Amalgamated Text,” BYU Studies 18 (Winter 1978): 205.

- Parley P. Pratt, The Essential Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1990), 57.

- Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1874–86) 3:92;

- Bruce R. McConkie "The Seven Deadly Heresies" Brigham Young University Devotional June 1, 1980 online at:https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/bruce-r-mcconkie/seven-deadly-heresies/