Union générale des israélites de France

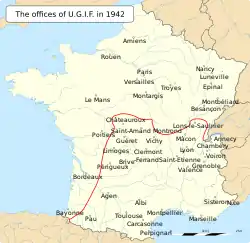

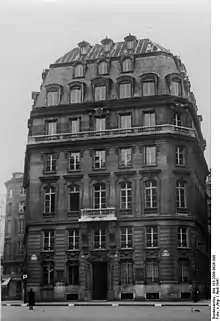

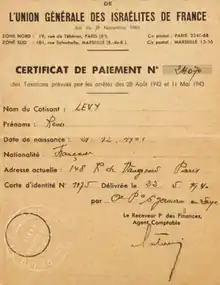

The Union générale des israélites de France (General Union of French Jews; UGIF) was an antisemitic body created by Xavier Vallat under the Vichy regime after the Fall of France in World War II. UGIF was created by decree on 29 November 1941 following a German request, for the express purpose of enabling the discovery and classification of Jews in France and isolating them both morally and materially from the rest of the French population.[1] It operated in two zones, one in the northern zone, chaired by André Baur, and one in the Southern Zone, under the chairmanship of Raymond-Raoul Lambert.[2] The mission of the UGIF was to represent Jews before the public authorities, particularly in matters of assistance, welfare and social reintegration. All Jews who were living in France were required to join the UGIF, because the other Jewish associations had been dissolved and their assets had been donated to the UGIF.[3] The administrators of this body mostly belonged to the French-Jewish bourgeoisie, administrators who were appointed by the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs (CGQJ), the structure which had been initiated by the Vichy government at the instigation of the Nazis to reinforce antisemitic persecution. In order to finance its activities, the UGIF drew on a solidarity fund whose income was generated from the confiscation of Jewish property,[4] from contributions from its members, and from funds from the CGQJ.[5]

The role of the organisation is controversial, particularly due to its legalism, which had transformed the offices of the association or the children's homes it sponsored into veritable mousetrap centre's particularly vulnerable to Gestapo raids. Composed essentially of conservative elements of the assimilated Jewish bourgeoisie, it was clearly accused by authors from left-wing Jewish groups of being a forum for collaboration with the Vichy regime, both ideologically and administratively.[6] Its action was indeed based on the postulate that the Jewish question in France was a problem of immigration and Jewish refugees from Eastern and Central Europe, and that French Jews, who were assimilated to the French bourgeoisie, could benefit from a certain ambiguity on the part of the Vichy regime. Unfortunately, from 1943 and the acceleration of the Final Solution in Europe, this fiction was to collapse and the collaborationist policy of the UGIF leaders led them directly to deportation to Auschwitz. After the war, a jury of honour[6] was established, in relative secrecy, without really deciding whether or not the UGIF was collaborationist. The late publication of the notebooks of one of the leaders of the UGIF,[7] by an Israeli historian,[7] makes it possible to understand, according to Claude Levy, Raymond Lévy's brother, that one of the sources of the collaboration of the UGIF and its leading members, came from their personal attachment to Marshal Pétain and their confidence in Xavier Vallat.

Historical background

Demographics

In 1940 there were about 300,000-330,000 Jews (0.7%)[8] in metropolitan France, among them 150,000 French citizens and 150,000 immigrants. Two thirds of them lived in the provinces, but the overwhelming majority of foreign Jews lived in the Paris region. Of the 150,000 French Jews, 90,000 were of old stock and of the 60,000 foreign Jews, they were often immigrants from Eastern Europe whom half were naturalized in the 1930s.[9]

On the eve of the war, French Jews formed a wealthy and cultured milieu. They belonged overwhelmingly to the bourgeoisie, often even to the French high bourgeoisie[10] which made them conservative of the social order.[10] They were established in all the cities and were completely assimilated into French culture, whereas foreign Jews lived mainly in Paris, were refugees from Eastern Europe who were mostly at the bottom of the social ladder, who often came from or were involved in revolutionary movements, and generally remained attached to Yiddishkeit, the symbol of fidelity to ancestral customs.[9]

Nomenclature

Since the creation by Napoleon in 1808 of the Israelite Central Consistory of France[11] French people of Jewish origin have never been referred to as "Jews", an expression that designates a race or a nation, but as "Israelites"[12] i.e. as citizens practising one of the four official religions and belonging entirely to the French Nation.[13] Jews who were agnostic, even anti-religious, did not recognize themselves in this official institution that was created to administer and maintain their worship, based on the centralized model of the Catholic Church in France, by strictly reducing Judaism to a religious denomination.

Immigrants and refugees

French Jews created philanthropic aid organisations for refugees, such as the Jewish Welfare Committee of Paris (Comité de bienfaisance israélite de Paris (CBIP)[14][15] founded in 1809[16] and the Refugee Aid Committee[17] (CAR) in 1938. The Eclaireuses et Eclaireurs israélites de France (EIF, Jewish Guides and Scouts of France), founded by Robert Gamzon, grandson of the Chief Rabbi of France Alfred Lévy in 1923,[18] had been involved since 1930 in the integration of Jewish immigrants from Germany and Eastern Europe.[19] For the refugees, the French are, at best, bad Jews, and at worst, traitors to their religion and their people.[20] The Jewish communities of Eastern Europe organised themselves, especially in Paris, by origin and political tendency.

Landsmanschaften

The Landsmanschaften, organisations by country or by region were grouped into a federation, the Federation of Jewish Societies of France (FSJF, Fédération des sociétés juives de France) that was founded in Paris in 1913.[21][22] From the 1930s it was known as the main representative of Jews immigrating to France. As well as providing sustenance and legal aid, it offered access to social and cultural activities.[21] Its president was Marc Jarblum,[23] was a leader of the Zionist movement. The political parties in which immigrant Jews were involved were the Bund, close to the French Section of the Workers' International and whom cultivated the Yiddish language and the Main-d'œuvre immigrée (MOI), integrated into the Communist International, and various Zionist parties, who were of especially of a socialist tendency.[20]

Children

The Œuvre de secours aux enfants (OSE, Children's Relief Society) was founded in 1912 in Tsarist St Petersburg by Jewish physicians to help underprivileged Jewish populations.[24] In 1922, the OSE created an international network of groups that has its headquarters in Berlin, under the name Union-OSE.[25] Albert Einstein became its first president.[25] The OSE moved its headquarters from Berlin to Paris in 1933 as a result of Nazi persecution within Germany.[25] It opened houses in the Paris region to take in Jewish children fleeing from Germany and Austria, then very soon afterwards to take in children living in France.[25] Among the many Jewish associations, Colonie Scolaire at 36 rue Amelot in Paris[26] became famous, because it was there on 15 June 1940, that representatives of a series of Jewish immigrant organisations met to form what was to become known as the Amelot Street Committee (Comité de la rue Amelot).[27] While functioning as an underground organisation it provided aid to refugees, internees and children.[27]

National coordination and distribution

The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, generally known as the JDC or Joint, distributed grants to local philanthropic institutions.[28] In June 1940, the JDC established its offices in Marseilles.[29] In 1941, the JDC distributed nearly $800,000, or about 65 million francs, which then represented more than 70% of the aid distributed as social assistance. In the summer of 1940, the director of the Joint decided to distribute the bulk of French aid through the Refugee Aid Committee rather than the Federation channel, which did not improve relations between the leaders of the two organisations [30] A large number of foreign Jews were then interned in camps. A network of aid to the camps developed from the end of 1940, with various Christian and Jewish charities. In October 1940, the Nimes Committee was established that brought together Jewish and Christian organisations, under the chairmanship of an American, Donald Lowry[17] to coordinate relief to the interned.[17] The Refugee Aid Committee settled in Marseille in August 1940.[31] At the end of 1940, the communists of the MOI created a self-help organisation, Solidarity (Solidarité), which aimed to help the needy, especially the wives of prisoners, and later the wives and families of internees.[32] Although Solidarity was a clandestine organisation, due to communism and communists being outlawed, although better organised, its activities were similar to those of the Amelot Street Committee.[33]

The Coordinating Committee

After the occupation of Paris in June 1940 and installation of the Vichy France government, the consistory withdrew to Lyon,[34] leaving the Association consistoriale des israélites de Paris (ACIP) to provide aid in Paris. In August 1940, the ACIP was approached by Sicherheitsdienst officer, Theodor Dannecker, the representative of the Gestapo Office of Jewish Affairs in France[35] to declare himself the official representative of French Jewry.[36] Dannecker demanded that Jewish Consistoire, which was the official religious organization of French Jewry, should be converted into a Judenrat.[37] As the Consistory's attributions were limited to worship alone, the ACIP had initially recused themselves but accepted under German pressure to set up a coordination committee. The Coordinating Committee of Charities of Greater Paris (Comité de Coordination des Oeuvres de Bienfaisance du Grand Paris) was established on 30 January 1941 in the northern zone, incorporating the ACIP's benevolent committee, representatives of the Amelot Street Committee, the OSE[38] and most other French and immigrant Jewish relief committees were affiliated with it to avoid dissolution.[39]

In the months following its creation, the committee remained under the predominant leadership of the men of the ACIP, but in March, Dannecker had imposed Israël Israelowicz and Wilhelm Biberstein, who had come from Vienna to be his proxies.[40] André Baur, nephew of Chief Rabbi Julien Weill, became Secretary General of the Committee. From July 1941, strong tensions appeared between the Committee and the immigrant populations: on 20 July, in order to confront a demonstration by 500 women internees, Léo Israélowicz asked Dannecker for protection.[40] The Committee succeeded in obtaining the release of a certain number of internees, but the immigrants became increasingly distant from the Committee. On 18 August 1941, Dannecker demanded 6,000 Jews for "agricultural work" in the Ardennes.[41] The Committee then asked for volunteers exclusively from among the immigrants. The volunteers were few in number and as a retaliatory measure, the Germans organised a round-up of 3,200 foreign Jews and 1,000 French Jews who were interned in Drancy internment camp.[40] At the end of August, the ACIP officially joined the committee.[40]

The Office of the Commissioner General for Jewish Affairs

At the request of German authorities,[42] the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs (CGQJ, Commissariat général aux questions juives) was created by the Vichy French Council of Ministers.[43] The enforcement decree implementing the law dates from 29 March 1941.[44] The CGQJ was initially under the authority of the Secretary of State for the Interior, Pierre Pucheu and then, from 6 May 1942, directly under that of the head of government, at that time Pierre Laval.[45] According to the Dannecker report of 1 July 1941, the CGQJ was created at the "repeated insistence" of the Jewish service of the embassy.[46] Dannecker was suspicious of the first commissioner,[47] the anti-Semitic Xavier Vallat, a former deputy of right-wing monarchist Action Française party.[42]

The Police for Jewish Affairs (PQJ) was officially created by a government decree by Pucheu in October 1941 together with the Anti-Communist Police Service (SPAC) and the Secret Society Police Service (SSS) intended to operate against freemasonry. [48][49] Before the creation of the PQJ, there was a small group of police officers in Paris under the leadership of Commissioner François and Judenreferat Dannecker.[50] In the whole of the southern zone, the PQJ had only about thirty employees, who were not well accepted by the Vichy administration. In the occupied zone, the PQJ never respected its legal limits: it could play the auxiliaries of the German police by harassing the Jews, but each time there was a round-up, the national police was called in and not the PQJ.[51]

The law of 2 June 1941, known as the Second law on the status of Jews (Statut des Juifs, Loi du 2 juin 1941 remplaçant la loi du 3 octobre 1940 portant statut des Juifs) which further restricted the professional practice of Jews, was adopted on the initiative of the CGQJ.[52] The law of 22 July 1941 enabled the CGQJ to control the Aryanisation of Jewish companies, which was in fact its essential work.[53] Aryanisation had already been implemented by German ordinances since the very beginning of the occupation.[54]

The Institute for the Study of Jewish Questions (IEQJ, Institut d'étude des questions juives) was responsible for promoting anti-Jewish propaganda and was established by Dannecker and the Propagandastaffel, and placed under the direction of anti-Semitic propagandist Captain Paul Sézille, who had no direct link with the CGQJ or any other Vichy administration.[55][56]

Creation of the Union Générale des Israélites de France

In the bureaucratic chain of persecution of Jews in 1941, the Coordinating Committee did not yet represent the indispensable link in the imposed, controlled organisation of the Jews. In Germany, the Reichsvereinigung grouped together Jews from all over the country. In Poland, a Judenrat was established in each locality by September 1940. In the countries of Western Europe, the centralised model, modelled on the Reich Association of Jews in Germany (Reichsvereinigung) was applied.[57] In February 1941, in the Netherlands it was the imposition of the Joodsche Raad (Dutch Jewish Council).[57]

Dannecker envisaged proceeding from German ordinance, to create such a body in the occupied zone,[58] but the military administrator (MBF. Militärbefehlshaber) preferred to collaborate with the Vichy regime by submitting a proposal to Xavier Vallat. He initially refused, but finally the French government conceded and created the UGIF on 29 November 1941.[59] The law of 1941, like all the legislative measures taken by Vichy against the Jews since the first anti-Semitic statute of October 1940, marks a break with republican and secular traditions.[60] According to Article 1 of the Law of 29 November, the purpose of this body

- "is to ensure the representation of Jews before the public authorities, particularly in matters of assistance, welfare and social reintegration"

both in the occupied and free zones, which the Germans had never requested, whereas Article 2 stipulated that all Jews domiciled or resident in France must be affiliated to it.[61]

In order to establish the compulsory organisation, Vallat consulted Jewish leaders from both zones such as Jacques Helbronner, president of the Consistoire, or Raymond-Raoul Lambert, director of the Refugee Aid Committee (CAR, Comité d'aide aux réfugiés). It is clear that the leadership of the future UGIF would only include French citizens. The project was the subject of lively debates between Vallat and his various interlocutors, but also among the Jews themselves. Some are resolutely hostile to the project, often because French Israelites would be treated in the same way as foreigners and those who have recently become naturalised.[62] In 1941, Helbronner accepted a leadership position in the UGIF, even though he was initially opposed to its establishment.[63]

UGIF absorbed social welfare organisations and their staff. The attachment to the survival of the works and the conviction that their proper functioning was in the supreme interest of the community characterised the reactions of the UGIF leadership and distinguished them from the leadership of the consistory.[62] Lambert identifies more than anyone else with the UGIF of the South and had good relations with Vallat.[62] On the immigrants' side, Marc Jarblum, president of the FSJF, was categorically opposed to the UGIF, but some OSA leaders did not see any incompatibility between the honour of the Jews and compromise with an imposed law.[62]

Before starting the foundation of the UGIF, Vallat initiated talks in Paris as he had done in the southern zone, but he completely ignored immigrant associations.[40] The leaders of the former Committee agreed to take over the leadership of the UGIF while pointing out in a letter to Pétain that they had no mandate from their "foreign co-religionists". Finally, the leadership of the UGIF was appointed on the 8 January 1942 and included Albert Lévy, former president of the CAR and first president of UGIF, André Baur, vice-president, and Raymond-Raoul Lambert, general administrator. Baur was from the North zone, while Lévy and Lambert were from the South zone.[40] In fact, although the UGIF is theoretically a single body, the branches of each of the two zones operated independently.[40] In the Southern zone, Lambert was the strong man of the UGIF, so much so that Lévy was described as "Lambert's toy".[64]

Aspects

In December 1941, following the series of attacks on the occupying army (see, for example: reprisals after the death of Karl Hotz), the Germans unleashed a wave of arrests in Paris which hit French Jews in particular: 743 of them were interned in Royallieu-Compiègne internment camp. Fifty-three Jewish hostages were shot at Mont-Valérien and the Militärbefehlshaber (MBF) announced the deportation of "Judeo-Bolshevik criminals" to the East. In March 1942, the first train to Auschwitz took 1,112 internees. The last reprisal measure, on 14 December 1941, the Jews were fined one billion francs.[65] Until March 1942, the Wehrmacht had authority over all matters, including Jewish affairs in France, whereas after this date, police matters and the implementation of the Final Solution were transferred to a SS and police leader (Höhere SS- und Polizeiführer) directly dependent on Reinhard Heydrich.[66]

On 17 September, the MBF's head of financial affairs, Elmar Michel, instructed the UGIF to collect the money. The UGIF then borrows some, committing all the income from the Aryanisation of Jewish property as collateral. In the end, it will use 895 million francs, i.e. a little over 40% of the proceeds of the Aryanisations, to finance the payment of the fine.[67] The French law on the Aryanisation of Jewish property, of 22 July 1941, had provided for the freezing of the sums collected from the sale of Jewish businesses. A part of these blocked assets was to be used to reimburse administrative expenses, the rest was to be used to help needy Jews.[68]

In the southern zone, the various social welfare agencies were grouped together by the UGIF to retain their autonomy, with part of their resources come from the United States. In November 1942, with the German occupation of the southern zone, this resource was blocked and the Jewish leaders obtained an order from the French authorities authorising the UGIF to levy an annual tax of 120 francs in the northern zone and 320 francs in the southern zone on all Jews over the age of eighteen. To the sums thus obtained was added an amount of 80 million francs from blocked funds.[67]

Summer 1942 deportations

In Eastern Europe, the Nazis involved the Judenrat in the deportation process. In some ghettos in Poland, Jewish community leaders provided lists of people to be deported. In France, the UGIF was not asked to carry out this task. Arrests were entrusted only to the French state police.[69]

Following various more or less organised leaks, the UGIF had been informed of the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup that took place on 16 and 17 July. However, the leaders of the organisation did not disseminate this information, which they could not yet identify with an Auschwitz they did not know about, but which could have suggested to them that it involved mass deportations.[69] After the Vel' d'Hiv round-up on 28 July, Lambert obtained confirmation from the national police of the rumours circulating about imminent deportations to the southern zone. The leading members of the UGIF did not meet until 31 August, and when Lambert met Laval on 31 July, by chance, he did not take the opportunity to ask him the question. Lambert wrote in his diary that it was up to Lévy, president of the UGIF, or Helbronner to take this kind of action. On 2 August, he had the opportunity to explain his position to Helbronner, who was part of the Jewish high bourgeoisie, whereas Lambert appeared as a simple ambitious social technician.[67] Raul Hilberg described Helbronner's words as criminal: "If Mr. Laval wants to see me, all he has to do is summon me, but tell him that from August 8 to September, I'm going on holiday and nothing in the world can make me come back.[70]

This attitude of the UGIF and of the French Jewish elite was later condemned quite severely by historians such as Jacques Adler, who put forward the hypothesis that "the leaders of the UGIF knew that the operations would only affect immigrants and they feared reprisals against themselves and French Jews.[71] Maurice Rajsfus accused the UGIF "of having lent its assistance to the Prefecture of Police concerning the round-ups of 16 and 17 July[72] without specifying whether this assistance consisted of other actions than the parcels that the UGIF was authorised to bring to the internees of Drancy from October 1942.[69] When, on 3 August, the Camp des Milles was cordoned off by 170 mobile guards, the various Jewish and Christian social aid organisations reinforced their presence. Lambert rushed to the camp alongside Donald Lowry, the Grand Rabbi of Marseille Israël Salzer and Pastor Henri Manen of Aix. Lambert, who was not yet aware of the nature of Auschwitz and the final solution wrote in his notebook:[73]

- Monday 10th August: a terrible day, a heartbreaking spectacle. Buses take 70 children away from their parents who will leave this evening... Framed by armed guards, 40 human beings who have committed no crime because they are Jews, are delivered by my country, which had promised asylum, to those who will be their executioners

In January 1943, the Marseille roundup provoked a protest signed by Chief Rabbi Salzer of Marseille, Rabbi René Hirschler Chaplain General, and Lambert on behalf of the UGIF of the Southern zone. The protest marked a change in the practices of the UGIF that until then had been strictly limited to the framework of social action [74]

Links with Jewish resistance

While resistance by Jews in other German occupied countries may have organised an armed response to oppose the policy of extermination directed against the Jewish population, Jewish resistance in France, consisting of rescue actions, was by far the most important.[75]

The absolute legalism of the UGIF forbade it to be classified as Jewish Resistance, which did not prevent the UGIF from maintaining all sorts of links with organisations such as the OSE, Rue Amelot or Solidarity, which one would not hesitate to classify as in Jewish Resistance. After the Vel' d'Hiv round-up, despite Pierre Laval's efforts to get the children to leave with their parents, many of the children who had managed to escape arrest were temporarily staying with neighbours or the caretaker. In its Information Bulletin, the UGIF of Paris requested that abandoned children be reported to it. Prior to the round-ups, children had already been entrusted to the UGIF, which had six children's homes. At the end of 1942, there were a total of 386 children in the houses run by the UGIF.[76] These became a rescue hub, while the task of hiding the children as quickly as possible under an Aryan identity fell to Solidarity, the OSE and Rue Amelot.[77] In fact, the clandestine organisations can take children entrusted to the UGIF out of their homes and put them in safe houses with foster families, with the exception of the category of "blocked children" because they have been registered by the Sicherheitsdienst. The so-called "blocked children" were children interned in Drancy internment camp with their parents, but who had not been deported, and who the UGIF has been authorised to take out of the camp to put them in children's "homes". Service 5 of the UGIF, led by Juliette Stern, took care of these children,[77] as did Orthodox Action for Children of Russian origin.

The UGIF leaders felt responsible not only for the safety of children but also for their Jewish education. In any case, the organisation did not have the means to take in all needy children. At the beginning of 1943, out of the 1,500 children entrusted to the UGIF, 1,100 were entrusted to foster families or to non-Jewish institutions.[77]

The crucial question of legality did not only arise in the UGIF. In 1943, the OSE, that practised illegal actions on a large scale, retained its legal cover and hesitated to proceed to a hasty dissolution of its children's homes, which risked becoming a mousetrap. It is certainly easier to run a children's home properly if it has a more or less official character.[78] On the 19 October 1943, the Marseille UGIF was informed that the Gestapo was preparing an operation at the Verdière home in the Bouches-du-Rhône. Like the "blocked children" in Paris, the children at La Verdière had been entrusted to the UGIF by the Gestapo. One of the leaders was of the opinion that the children should be dispersed, but Lambert's replacement - already interned in Drancy - decided to play the legality card. On 20 October, the Gestapo took all the boarders, thirty Jewish children and fourteen adults, including nine mothers to Drancy then to Auschwitz.[79] The director of the château Alice Salomon, decided to accompany the children being deported.[78] From the beginning of 1943, the legalism of the UGIF was denounced by rescue organisations more involved in clandestinity. In February 1943, Solidarity carried out a kind of kidnapping by clandestinely taking 163 children out of the UGIF homes.[80]

Arrests of UGIF members

The deportations of the summer of 1942 had shown that being an employee of UGIF offered relative protection against arrest. The same German practice was found in the Judenrat of Eastern Europe. However, in 1943, this protection offered by the UGIF became increasingly illusory.[81]

Without any known German pressure, the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs decided to abolish the legal protection still enjoyed by immigrants employed by the UGIF. The virulently anti-Semitic Louis Darquier de Pellepoix,[82] Vallat's successor since May 1942, and cabinet director Antignac had contacts in this regard with Baur and Lambert, mostly separately. It was finally in March that the dismissal of foreign personnel was imposed in both zones.[81] In Paris, Heinz Röthke, Dannecker's deputy, immediately arrested the dismissed employees during the night of 17 to 18 March. Many former employees could be warned, but 60 to 80 people were still rounded up.[81] The police were also able to arrest many former employees. In the southern zone, under the single facade of the UGIF, the various social aid organizations operated practically independently. Thus, in Lyon, at 12 Rue Sainte-Catherine, the OSE, the CAR and the Federation were based at the UGIF premises. On February 9, 1943, the local Gestapo commanded by Klaus Barbie raided these offices and arrested 84 people, employed or assisted, who were immediately transferred to Drancy (Rue Sainte-Catherine Roundup). The pretext was that these organizations were helping immigrants to escape to Switzerland with false papers, which corresponded to a certain reality.[81] The same kind of scenario was repeated in Marseilles, after two SS men were killed by the Resistance on May 1: Bauer, Röthke's delegate in Marseilles, asked Lambert for a list of 200 Jewish notables. Lambert refused, but the following day Bauer carried out a raid on the offices of the UGIF in Marseilles.[81] The list of 200 Jewish notables was sent to Lambert.

In Paris, the financial situation of the UGIF was much worse than in the Southern zone even after March 1943, when Baur succeeded in convincing Lambert to transfer funds. From May, Jews were able to make "donations" to the UGIF and the Commissariat decreed a tax of 120 francs per Jewish adult in the Northern zone and 360 francs in the Southern zone. The results of this new tax were very meagre, since the lists of Jews from the 1940 census were becoming less and less reliable, with more and more Jews living illegally.[81] The results of this new tax were very meagre.

In the Southern zone, in 1944, the offices of the UGIF became veritable mousetraps. It seems that when the German regional commanders had to provide a certain number of Jews, they went to the simplest of lengths. Round-ups thus took place in Nice, Lyon, Marseille, Chambéry, Grenoble, Brive and Limoges.[83]

Income Assistance

Welfare represented more than half of UGIF's budget and consisted of soup kitchens and direct aid distributed directly to the most needy. The soup kitchens depended in part on Rue Amelot. 2,500 needy people received aid from the UGIF at the beginning of 1942. From the end of 1942, they numbered about 10,000. There is no evidence that lists of UGIF aid recipients could have been used to arrest the families.[81] The UGIF was not able to arrest the families.

The UGIF was also active in the camps in the Northern zone. These included parcels of food, clothing, and hygiene products. Through its interventions the UGIF obtained several hundred releases. As of July 1943, these interventions were no longer of any use.[81]

Arrests

In the first three months of 1943, despite the determination of the Nazis to continue the deportations, and the opportunity created by the invasion of the former free zone, it appeared that France was lagging behind other European countries. The slow progress of the Germans gave hope to Lambert, who rejected the suggestion made by one of his colleagues to advise the Jews of Marseille to disperse (Marseille roundup). Confident in the justice and honour of France," writes Hilberg,

On 21 August 21, 1943 Lambert and his family were arrested and interned in Drancy before being deported to Auschwitz.[86] He wrote to one of his former assistants to request that the Jewish children entrusted to the UGIF refuges be dispersed.[84]

A month before Lambert's arrest, André Baur, head of the UGIF in Paris had already been arrested. At the end of June 1943, the new head of the Drancy camp, Alois Brunner, had asked the UGIF to use its influence to ensure that the families of the internees voluntarily joined them at Drancy. Baur had refused and asked to be received by Laval. It was the first time he had made such a request since his appointment to the UGIF. He had requested the interview of Antignac, secretary general of the CGQJ. Ten days later, he was arrested and interned in Drancy.[81] A week later, Israélowicz, the Viennese imposed by the SD was also arrested.[81] Helbronner, the president of the consistory was arrested on the 23 October 1943.[87]

The final days of UGIF

In 1944, before the departure of the Germans, when the last deportation campaign was launched, many of the 30,000 Jews living in Paris in broad daylight only benefited from the help of the UGIF, which also took care of 1,500 children entrusted to its care.[88] The fact that the Germans seemed to have given up making round-ups of Jews in the Paris region one of their priorities did not prevent Brunner from launching a series of operations on the children's homes of the Parisian UGIF in July 1944, three weeks before the liberation of Paris. 250 children were arrested and deported whereas the clandestine networks were able to take care of all the children entrusted to the UGIF, including the "blocked children ".[88][89]

Not only did the UGIF did not accept the proposals of the clandestine organisations, but Georges Edinger, André Baur's successor, procrastinated and after having ordered the dispersal of the children and staff, reversed his decision and makes everyone come back, including the children.[90] These latest arrests, which could have been avoided, are the biggest charge Serge Klarsfeld has brought against the UGIF.

- This shameful task has marked the UGIF forever, leading to the neglect of the contribution of this institution, initially designed by the Germans to facilitate the Final Solution and which, undeniably, statistically speaking, has helped the Jews much more than it has served them [91]

Wording of the Decree

The wording of the decree that created the Union générale des israélites de France on 29 November 1941.[92]

We, Marshal of France, Head of the French State, the Council of Ministers, having heard the following decrees:

- Article 1. - A General Union of Israelites of France is hereby established within the Commissariat aux Questions Juives. The purpose of this Union is to ensure the representation of the Jews before the public authorities, in particular for questions of assistance, welfare and social rehabilitation. It fulfils the tasks entrusted to it in this field by the government. The Union générale des Israélites de France is an autonomous public institution with civil personality. It is represented in court as well as in acts of civil life by its president, who may delegate all or part of his powers to an agent of his choice.

- Article 2. - All Jews domiciled or resident in France must be affiliated to the General Union of Israelites of France. All Jewish associations are dissolved with the exception of legally constituted Jewish religious associations. The property of the dissolved Jewish associations devolves to the Union générale des Israélites de France. The conditions for the transfer of these assets will be fixed by decree issued on the report of the Secretary of State for the Interior.

- Article 3. - The resources of the General Union of Israelites of France are made up of: 1°, By the sums that the General Commissariat for Jewish Questions deducts for the benefit of the Union from the Jewish solidarity funds instituted by article 22 of the law of 22 July 1941. 2°, By the resources coming from the property of the dissolved Jewish associations. 3°, by contributions paid by Jews, the amount of which is fixed by a Board of Directors of the Union according to the financial situation of those subject to the fund and according to a scale approved by the Commissioner General for Jewish Questions.

- Article 4. - The General Union of Jewish Women of France is administered by a Board of Directors of eighteen members chosen from among Jews of French nationality, domiciled or resident in France and appointed by the General Commissioner for Jewish Questions.

- Article 5. - The Board of Directors is placed under the control of the Commissioner General for Jewish Affairs. The members are accountable to him for their management. The deliberations of the Board of Directors may be cancelled by order of the Commissioner General for Jewish Affairs.

- Article 6. - The contributions fixed by the Board of Directors of the General Union of Israelites of France are collected by enforceable statements as provided for in article 2 of the decree of 30 October 1935.

- Article 7. - As long as the communication difficulties resulting from the occupation remain, the Board of Directors may be divided, if necessary, into two sections whose headquarters will be determined by the General Commissioner for Jewish Affairs. Each section shall consist of nine members and shall be chaired by the Chairman and the Vice-Chairman.

- Article 8. - The present decree shall be published in the Official Gazette and executed as a law of the State.

Done at Vichy, 29 November 1941.

The text was signed by Philippe Pétain, François Darlan, Joseph Barthélemy, Pierre Pucheu and Yves Bouthillier.

Literature

- Adler, Jacques (1985). Face à la persécution : les organisations juives à Paris de 1940 à 1944. Paris: Calmann-Lévy. ISBN 9782702113455. OCLC 477153811.

- "The Organization of the "Ugif" in Nazi-Occupied France". Jewish Social Studies. Indiana University Press. 3 (3): 239–256. July 1947. JSTOR 4464773.

- Hazzan, Suzette (2007). "La maison de la Verdière à La Rose : d'une halte précaire à la déportation des enfants et des mères". Provence-Auschwitz: De l'internement des étrangers à la déportation des juifs 1939-1944. Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence. pp. 181–202. doi:10.4000/books.pup.6872. ISBN 9782821885578.

- Kaspi, André. (1997). Les Juifs pendant l'Occupation (in French) (Éd. rev. et mise à jour par l'auteur ed.). Paris: Éd. du Seuil. ISBN 9782020312103. OCLC 1063258628.

- Klarsfeld, Serge (1983). Vichy-Auschwitz : le rôle de Vichy dans la solution finale de la question juive en France (in French). [Paris]: Fayard. ISBN 9782213015736. OCLC 958199681.

- Laffitte, Michel (2001). "Between Memory and Lapse of Memory". In Roth, John K; Maxwell, Elisabeth; Levy, Margot; Whitworth, Wendy (eds.). Remembering for the Future: The Holocaust in an Age of Genocide. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 674–687. ISBN 978-1-349-66019-3.

- Poznanski, Renée. "Jewish Responses to Persecution: The Case of France". EHRI. Amsterdam: European Holocaust Research Infrastructure. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Rajsfus, Maurice (1980). Des juifs dans la collaboration : l'UGIF (1941-1944) : précédé d'une courte étude sur les juifs de France en 1939. Paris: Etudes et documentation internationales. ISBN 9782851390578.

- Lambert, Raymond-Raoul; Richard I Cohen; United States Holocaust Memorial Council (2007). Diary of a witness: 1940-1943 (English ed.). Chicago: Chicago Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 9781566637404. OCLC 934223973.

Monograph

- Schwarzfuchs, Simon (1998). Aux prises avec Vichy : histoire politique des Juifs de France, 1940-1944 (in French). Paris: Calmann-Lévy. ISBN 9782702128237. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Archives

- Lauvergeon, Cécile. "Union générale des israélites de France (U.G.I.F.)". EHRI (in French). EHRI Consortium. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Union générale des Israélites de France (U.G.I.F.)". France Archives (in French). Archives de France. AJ/38/5777-AJ/38/5808, AJ/38/6383-AJ/38/6404. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Archives de l'Union générale des Israélites de France, commission des campsE". Archival Portal Europe. Archival Portal Europe Foundation. Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

See also

Citations

- Ayoun & Bennett 2005, pp. 85–103.

- "L'Union générale des Israélites de France (UGIF)" (PDF). Akadem (in French). Fonds Social Juif unifié, Holocaust Memorial Foundation. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Ayoun & Bennett 2005, p. 94.

- Fogg 2017, p. 49–55.

- Curtis 2002, p. 418.

- Rajsfus 1980.

- Lévy 1985, pp. 146–147.

- Poznanski, Renée. "Jewish Responses to Persecution: The Case of France". EHRI online course in holocaust studies EHRI. NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 4d. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Bédarida & Bédarida 1993, pp. 149–182.

- Poznanski 2001, pp. 3-4.

- Bonaparte 1808.

- Schnapper, Bordes-Benayoun & Raphael 2011, p. 1.

- Adler 2003, p. 13.

- Lazare 1996, pp. 44–45.

- Edelheit 2018, p. 351.

- Aboulker 2018, pp. 33–48.

- Wieviorka 2016, p. 208.

- Kieval 1980, pp. 339–366.

- Schor 1985, p. 191.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 28–29.

- "1 FONDS FSJF-APRÈS-GUERRE (MDLXXXIV)FÈDÈRATION DES SOCIÈTÈS JUIVES DEFRANCE, 1944–1994 2017.21.1, RG-43.161" (PDF). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives (in French). Biographical Information. February 2017. p. 2. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Rozett & Spector 2013, p. 211.

- Fineltin, Marc. "JARBLUM Marc, Mordehaï". Mémoire et Espoirs de la Résistance (in French). Association des amis de la Fondation de la Résistance. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Patrick Henry (20 April 2014). Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis. CUA Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8132-2589-0. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Children's Aid Society.

- Yivo Institute For Jewish Research, p. 358.

- Yivo Institute For Jewish Research 2019, p. 358.

- Beizer 2017.

- Curtis 2002, p. 214.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 107–108.

- Cohen 1993, p. 101.

- Mordecai Paldiel (1 April 2017). Saving One's Own: Jewish Rescuers During the Holocaust. University of Nebraska Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-8276-1297-6. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 83–84.

- Alexandra Garbarini (16 August 2011). Jewish Responses to Persecution: 1938–1940. AltaMira Press. p. 519. ISBN 978-0-7591-2041-9. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Renée Poznanski (2001). Jews in France During World War II. University Press of New England. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-58465-144-4. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 84–85.

- Szajkowski, Zosa (July 1947). "The Organization of the "Ugif" in Nazi-Occupied France". Jewish Social Studies. Indiana University Press. 9 (3): 243. JSTOR 4464773.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 84-85.

- "Comité de Coordination des Oeuvres de Bienfaisance du Grand Paris". EHRI. EHRI Consortium. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 174-176.

- Adler 2014, p. 41.

- Geoffrey P. Megargee; Joseph R. White (29 May 2018). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, Volume III: Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. Indiana University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-253-02386-5. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- "Commissariat général aux questions juives et Service de restitution des biens des victimes des lois et mesures de spoliation" [General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs and Service for the Restitution of Property of Victims of Spoliation Laws and Measures]. Archives of France. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "Décrets, Arrêtés, Circulaires". Journal of the French Republic (in French). Laws and decrees: Gallica. 90 (1): 1387. 31 March 1941. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Cohen 1993, p. 130.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 127-128.

- Taguieff, Pierre-André; Kauffmann, Grégoire; Lenoire, Michaël (1999). L'antisémitisme de plume, 1940-1944: études et documents (in French). Berg. p. 95. ISBN 978-2-911289-16-3. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Berlière, Jean-Marc; Chabrun, Laurent (2001). Les policiers français sous l'Occupation : d'après les archives inédites de l'épuration [French policemen under the Occupation: according to the unpublished archives of the purges] (in French). Paris: Perrin. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9782262016265. OCLC 421901027.

- Kitson, Simon (1 May 2014). Police and Politics in Marseille, 1936-1945. BRILL. p. 75. ISBN 978-90-04-26523-3. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Cohen 1993, p. 134.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 135-136.

- Cohen 1993, p. 136.

- Cohen 1993, p. 138.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 116-117.

- Cohen 1993, p. 150.

- "Institut D'études des Questions Juives,1941‐1953" (PDF). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Administrative history: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 166-167.

- Michael Robert Marrus; Robert O. Paxton (1995). Vichy France and the Jews. Stanford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8047-2499-9. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 169.

- Laffitte, Michel (2006). "L'UGIF, collaboration ou resistance?". Revue d;Histoire de la Shoah (in French). 185 (2): 45. doi:10.3917/rhsho.185.0045.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 169-170.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 171-173.

- Henry, Patrick, ed. (2014). Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press. p. 88. ISBN 9780813225890. OCLC 861497294.

- Szajkowski, Zosa (1966). Analytical Franco-Jewish Gazetteer, 1939-1945. Judaic studies collection. sn. p. 57. LCCN 66008041. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 176-177.

- Jäckel, Eberhard (1968). La France dans l'Europe de Hitler. Les Grandes études contemporaines (in French). Paris: Fayard. pp. 280–284. OCLC 567977372.

- Hilberg 2006, pp. 1162–1166.

- Hilberg 2006, p. 1145.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 274-276.

- Hilberg 2006, pp. 1182-1184.

- Adler, Jacques (1985). Face à la persécution : les organisations juives à Paris de 1940 à 1944. Collection Diaspora. Paris: Calmann-Lévy. p. 112. ISBN 9782702113455. OCLC 477153811.

- Rajsfus, Maurice (1980). Des juifs dans la collaboration : l'UGIF (1941-1944) : précédé d'une courte étude sur les juifs de France en 1939 (in French). Paris: Etudes et documentation internationales. p. 308. ISBN 9782851390578. OCLC 615345891.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 286-287.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 339-340.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 363-365.

- Adler, Jacques (1985). Face à la persécution : les organisations juives à Paris de 1940 à 1944. Collection Diaspora. Paris: Calmann-Lévy. p. 114. ISBN 9782702113455. OCLC 477153811.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 366-372.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 464-465.

- Hazzan, Suzette (2007). "La maison de la Verdière à La Rose : d'une halte précaire à la déportation des enfants et des mères". In Mencherini, Robert (ed.). Provence-Auschwitz: De l'internement des étrangers à la déportation des juifs 1939-1944 (in French). Presses universitaires de Provence. pp. 181–202. ISBN 9782821885578. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Kaspi, André (1997). Les Juifs pendant l'Occupation. Points., History;, H238. (in French) (Revised and updated ed.). Paris: Seuil. pp. 347–348. ISBN 9782020312103. OCLC 1063258628.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 403-410.

- Goodfellow, Samuel (2008). "Goodfellow on Lambert, 'Diary of a Witness, 1940-1943'". H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. Michigan State University Department of History. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 481-482.

- Hilberg 2006, pp. 1209-1210.

- Raymond-Raoul Lambert (15 October 2007). Diary of a Witness, 1940-1943. Ivan R. Dee. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4617-3950-0. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Goodfellow, Samuel (2008). "Goodfellow on Lambert, 'Diary of a Witness, 1940-1943'". H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. Michigan State University Department of History. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Klarsfeld 1983, pp. 86-87.

- Hilberg 2006, pp. 1216.

- Cohen 1993, pp. 494-500.

- Adler 2014, p. 154.

- Klarsfeld 1983, p. 175.

- Danièle Lochak (6 November 2019). Le droit et les juifs. En France depuis la Révolution - 2e éd (in French). Dalloz. p. 96. ISBN 978-2-247-19824-5. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

Bibliography

- Aboulker, Marie (2018). "Le Comité de bienfaisance israélite de Paris: Ses membres dans l'espace philanthropique parisien (1887-1905)". Histoire urbaine (in French). n° 52 (2). doi:10.3917/rhu.052.0033. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Adler, Jacques (1 April 2014). Face à la persécution: Les organisations juives à Paris de 1940 à 1944. Calmann-Lévy. ISBN 978-2-7021-5268-3. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Adler, K. H. (7 August 2003). Jews and Gender in Liberation France. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-43550-5. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Ayoun, Richard; Bennett, Ofra (2005). "אהרון אפלפלד באיטליה / Les allemands et l'union générale des israélites de France" [The Germans and the General Union of Israelites in France]. Revue Européenne des Études Hébraïques (in French). Institut Europeén d'Études He'braiques. 11. JSTOR 23492924.

- Bédarida, François; Bédarida, Renée (1993). "La Persécution des Juifs". In Azéma, Jean-Pierre; Bédarida, François (eds.). La France des années noires: De l'Occupation à la Libération. France des années noires (in French). 2. Paris: Seuil. pp. 149–182. ISBN 9782020183048. OCLC 474077715.

- Beizer, Michael (25 July 2017). "American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Bonaparte, Napoleon (17 March 1808). "Imperial decree of 17 March, 1808, prescribing measures for the execution of the regulation of 10 december, 1806, regarding the Jews". Fondation Napoléon. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Children's Aid Society (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants)". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 23 August 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Cohen, Asher (1993). Persécutions et sauvetages: Juifs et Français sous l'Occupation et sous Vichy [Persecutions and rescues: Jews and French under the Occupation and under Vichy]. Histoire (in French). Paris: Editions du Cerf. ISBN 9782204044912. OCLC 30070726.

- Curtis, Michael (2002). Verdict on Vichy: Power and Prejudice in the Vichy France Regime. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970-689-6. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Edelheit, Abraham; Edelheit, Hershel (8 October 2018) [1st pub. 1994:Westview Press]. History Of The Holocaust: A Handbook And Dictionary. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-96228-8. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Fogg, Shannon Lee (2017). Stealing Home: Looting, Restitution, and Reconstructing Jewish Lives in France, 1942–1947. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-878712-9. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- Hilberg, Raul (2006). La destruction des juifs d'Europe. Folio/histoire, 142-144. (in German) (Final, completed and updated ed.). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 9782070309856. OCLC 85366683.

- Kieval, Hillel J. (10 October 1980). "Legality and Resistance in Vichy France: The Rescue of Jewish Children". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society. 124 (5). JSTOR 986573.

- Klarsfeld, Serge (1983). Vichy-Auschwitz : le rôle de Vichy dans la solution finale de la question juive en France [Vichy-Auschwitz: the role of Vichy in the final solution of the Jewish question in France] (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 9782213015736.

- Lazare, Lucien (1996). Rescue as Resistance: How Jewish Organizations Fought the Holocaust in France. Translated by Green, Jeffrey M. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10124-0. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Lévy, Claude (1985). "Lambert Raymond-Raoul, Carnet d'un témoin, 1940–1943" [Lambert Raymond-Raoul, Witness Notebook, 1940–1943]. Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire (in French). Persee. 8. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- Poznanski, Renée (2001). "1940:Jews and Israelites in France". Jews in France During World War II. University Press of New England. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-58465-144-4. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Rajsfus, Maurice (1980). Des juifs dans la collaboration: l'UGIF (1941–1944): précédé d'une courte étude sur les juifs de France en 1939 [Jews in collaboration: UGIF (1941–1944): preceded by a short study on the Jews of France in 1939] (in French). Paris: Etudes et documentation internationales. ISBN 2-85139-057-0.

- Rozett, Robert; Spector, Shmuel (26 November 2013). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-96950-9. OCLC 869091747. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Schnapper, Dominique; Bordes-Benayoun, Chantal; Raphael, Freddy (31 December 2011). Jewish Citizenship in France: The Temptation of Being among One's Own. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-4456-7. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Schor, Ralph (1985). "L'Esprit de Communauté". L'opinion française et les étrangers en France, 1919–1939 (in French). Publications de la Sorbonne. ISBN 978-2-85944-071-8. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- Wieviorka, Olivier (26 April 2016) [1st pub. 2013: Éditions Perrin, Paris]. The French Resistance. Translated by Todd, Jane. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97039-7. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Yivo Institute For Jewish Research (8 August 2019). "Rue Amelot (France)". Guide to the YIVO Archives. Taylor & Francis. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-315-50319-6. Retrieved 19 October 2020.