Typhoon Joe (1980)

Typhoon Joe, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Nitang, affected the Philippines, China, and Vietnam during July 1980. An area of disturbed weather formed near the Caroline Islands on July 14. Shower activity gradually became better organized, and two days later, the system was upgraded into a tropical depression. On July 18, the depression was classified as Tropical Storm Joe. Initially, Joe moved northwest, but began to turn to the west-northwest, anchored by a subtropical ridge to its north. Joe started to deepen at a faster clip, and attained typhoon intensity on July 19. The eye began to clear out, and the next day, Joe reached its highest intensity. Shortly thereafter, Joe moved ashore the Philippines. There, 31 people were killed and 300,000 others were directly affected. Around 5,000 homes were destroyed, resulting in an additional 29,000 homeless. Damage in the nation was estimated at $14.5 million (1980 USD).[nb 1]

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 3 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

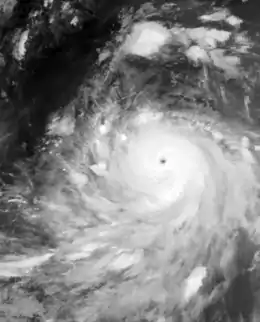

Joe during the late morning hours of July 20 | |

| Formed | July 15, 1980 |

| Dissipated | July 24, 1980 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 155 km/h (100 mph) 1-minute sustained: 195 km/h (120 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 940 hPa (mbar); 27.76 inHg |

| Fatalities | 351 total |

| Damage | $14.5 million (1980 USD) |

| Areas affected |

|

| Part of the 1980 Pacific typhoon season | |

The storm weakened rapidly over land, but re-intensified over the open waters of the South China Sea. Joe crossed the Leizhou Peninsula on July 22, where it became the strongest system to hit the peninsula in 26 years. A total of 188 people were killed in the area. Further north, in Hong Kong, two people were killed and 59 were injured. After weakening slightly, Joe made its final landfall in Vietnam while still at typhoon intensity. In Vietnam, 130 people were killed, 300,000 were directly affected, 165,000 lost their homes, 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) of rice paddies were flooded. In addition, 15,800 buildings were destroyed while 16,300 homes were flooded. Inland over Vietnam, Joe dissipated on July 24.

Meteorological history

An area of disturbed weather developed over the Caroline Islands on July 14. Tracking westward, convective activity gradually increased in both convection and coverage.[1] At 18:00 UTC on July 22, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) started tracking the system.[2][nb 2] Less than four hours later, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert (TCFA). On July 16, a Hurricane Hunter aircraft found a weak surface circulation and minimum sea level pressure of 1006 mbar (29.7 inHg). Initially, the low- and mid-level circulations were not vertically stacked, with the low-level center exposed from the deep convection. By 00:00 UTC on July 17, the surface center and the deep convection moved closer together, prompting the JTWC to classify the system as Tropical Depression 09.[1] Post-season analysis indicated that the depression had actually developed about 24 hours earlier than initially indicated.[4] Meanwhile, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) also monitored the storm and assigned it with the local name Nitang.[5]

Moving northwest in response to a shortwave trough an elongated area of lower air pressure aloft that was passing to its east,[1] the newly developed depression passed approximately 300 km (185 mi) west-southwest of Guam.[6] The depression began to develop at a quicker pace, and early on July 18, the JTWC upgraded it to a tropical storm.[7][nb 3] Six hours later, the JMA declared Joe a tropical storm.[2] At this time, the tropical system was located roughly 555 km (345 mi) west of Guam.[6] Joe then began to move on a constant and brisk westward course that it would maintain for the rest of its life in response to an unusually strong subtropical ridge that was east of its climatological position and to the north of the cyclone.[1] After Joe developed a central dense overcast – a large mass of deep convection,[6] the JMA upgraded Joe into a severe tropical storm.[2] At midday, hints of an eye became apparent on satellite imagery,[6] which led to the JTWC and JMA upgrading Joe into a typhoon.[7] This intensity estimate was confirmed by a Hurricane hunter plane later on July 19, which measured a pressure of 974 mbar (28.8 inHg). An eye began to clear out on July 20. That same day, a Hurricane hunter aircraft recorded a pressure of 940 mbar (28 inHg).[6] At midday, the JTWC estimated that Joe peaked in intensity, with winds of 195 km/h (120 mph), equal to a Category 3 hurricane on the United States-based Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS). Meanwhile, the JMA estimated maximum intensity of 160 km/h (100 mph).[7]

Six hours after its peak, Joe made landfall in central Luzon.[1] At the time of landfall, the JMA indicated winds of 90 mph (145 km/h).[2] Over land, Joe weakened rapidly, falling to tropical storm strength according to the JTWC.[1] After entering the South China Sea on July 21, the JTWC expected Joe to turn northwest and threaten China. However, this did not occur due to the strong ridge to its north. Joe began to re-intensify; data from the JTWC suggested that Joe regained typhoon intensity almost immediately thereafter.[1] Around this time, the JMA estimated that Joe reached its secondary peak of 135 km/h (85 mph). At 00:00 UTC on July 22, the JTWC estimated that Joe attained a secondary peak of 170 km/h (105 mph) based on a Dvorak classification of T5.0. Despite maintaining its structure[1] as it tracked over the Leizhou Peninsula, the storm weakened as it entered the Gulf of Tonkin[6] and approached the coast of Vietnam.[4] Both the JTWC and JMA agree that Joe had winds of 130 km/h (80 mph) when it moved ashore near Haiphong in Vietnam later on July 22.[1][7] A combination of land interaction and vertical wind shear resulted in rapid weakening. At 00:00 UTC on July 23, the JTWC issued its last warning on Joe. The remnants of Joe later moved into Laos.[1] The JMA stopped watching Joe on July 24.[2]

Preparations and impact

Prior to its first landfall, storm warnings were posted for most of the Philippines.[9] Across the Philippines, 31 citizens were killed,[10] including eight fisherman.[11] There, 300,000 people were directly affected.[10] Around 5,000 homes were destroyed, resulting in an additional 29,000 homeless.[11] Damage totaled $14.5 million.[10] Less than a week later, the same areas were affected by Typhoon Kim.[12][13]

The typhoon also tracked over the Leizhou Peninsula, becoming the strongest system to affect the region in 26 years.[6] Two large ships, a 20,000 short tons (18,145 t) liner and a 50,000 short tons (45,360 t) tanker, were washed ashore in Chankiang.[14] Throughout the area, 188 people were killed and at least 100 others were left homeless.[10] Further north, in Hong Kong, a No 1. hurricane signal was issued early on July 21. Later that day, the signal was increased to a No 3. hurricane signal and then elevated to a No 8. hurricane signal. All signals were dropped late on July 22, after Joe made its closest approach to Hong Kong. A minimum pressure of 1001.2 mbar (29.57 inHg) was recorded at the Hong Kong Royal Observatory (HKO) early on July 22. Tate's Cairn recorded a peak wind speed of 87 km/h (54 mph) and a peak wind gust of 154 km/h (96 mph) occurred in Stanley. HKO observed 61.9 mm (2.44 in) of rain over a 72-hour period. Within the vicinity of Hong Kong, two people were killed at a construction site in Kwai Chung. A total of 59 people were injured,[6] including seven that were hospitalized,[15] most from fallen debris. Three boats were also lost at sea after their anchors to the harbor broke. Air and sea traffic came to a halt. Overall, damage in the Hong Kong area was slight.[6]

In Vietnam, 130 people were killed, 300,000 others were directly affected, and 165,000 others lost their homes.[10] An additional 15,800 buildings were destroyed, 16,300 homes were flooded, and many boats sunk.[16] The storm inundated 20,235 ha (50,000 acres) of rice paddies, uprooted trees, and blew off roofs from houses.[17] It also brought additional flooding to provinces of Ha nam ninh, Ha bac, Hai hung, and Ha son binh; these areas were already inundated by prior flooding.[18]

See also

- Similar early season Philippine typhoons

Notes

- All currencies are converted to United States Dollars using Philippines Measuring worth with an exchange rate of the year 1980.

- The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[3]

- Wind estimates from the JMA and most other basins throughout the world are sustained over 10 minutes, while estimates from the United States-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center are sustained over 1 minute. 10‑minute winds are about 1.14 times the amount of 1‑minute winds.[8]

References

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center (1981). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1980 (PDF) (Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Japan Meteorological Agency (October 10, 1992). RSMC Best Track Data – 1980–1989 (Report). Archived from the original (.TXT) on December 5, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo – Typhoon Center 2000" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. February 2001. p. 3. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Typhoon 9W Best Track (TXT) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. December 17, 2002. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- Padua, Michael V. (November 6, 2008). PAGASA Tropical Cyclone Names 1963–1988 (TXT) (Report). Typhoon 2000. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Hong Kong Observatory (1981). "Part III – Tropical Cyclone Summaries". Meteorological Results: 1980 (PDF). Meteorological Results (Report). Hong Kong Observatory. pp. 22–24. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1980 Joe (1980197N07154). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Christopher W Landsea; Hurricane Research Division (April 26, 2004). "Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions:. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "International News". Associated Press. July 20, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Disaster History: Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900–Present (PDF) (Report). United States Agency for International Development. August 1993. pp. 147, 168. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "Typhoon Joe Blasts Philippines, Hong Kong". Associated Press. July 22, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Destructive Typhoons 1970–2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2004. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Destructive Typhoons 1970–2003 (Report). National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2004. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "Report 188 Chinese Die In Typhoon". Associated Press. July 27, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "International News". Associated Press. July 22, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "International News". Associated Press. August 3, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Second Typhoon In Week Hits Philippines". Associated Press. July 25, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "typhoon sweeps northern viet nam". Xinhua General News Service. July 24, 1980. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)