Tugboats in New York City

The tugboat is a New York City icon. Once all steam powered, they soon became iconic, starting with the first hull, the paddler tug Rufus W. King of 1828.

Context and early history

New York Harbor at the confluence of the East River, Hudson River, and Atlantic Ocean is among the world's largest natural harbors and was chosen in the 17th century as the site of New Amsterdam for its potential as a port. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 to the upper Hudson River ensured that New York would be the center of trade for the Eastern Seaboard, and as a result, the city boomed. At the port's peak in the period of 1900–1950, ships moved millions of tons of freight, immigrants, millionaires, and GI service men serving in wars.

Shepherding the traffic around the harbor were hundreds of tugs; over 700 steam tugs worked the harbor in 1929. Firms such as McAllister, and Moran Tugs came into the business. Cornelius Vanderbilt started his empire with a sailboat and went on to greatness with the New York Central Railroad, incidentally owning many tugs.

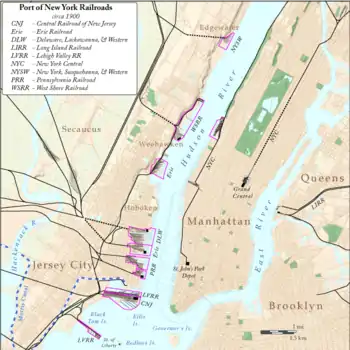

After the American Civil War, New York became a focal point of railroads including the Erie, Pennsylvania, B & O, Lackawanna, and Long Island. New York's geography, with Manhattan separated from the main part of the continent by the large Hudson River, presented a problem. Ferries took people over to the New Jersey side to board westbound trains. Freight was a more difficult problem which was solved by the car float, or car barge which would take loaded boxcars into town for unloading at freight sheds. Each railroad had its own freight sheds. Over 600,000 railcars were moved around the port annually. 19th century pictures of New York show the island bristling with hundreds of piers. Freight was manually unloaded from the boxcars, still on the barge, and wheeled by dolly across ramps onto the freight shed. To move the large number of barges, steam tugs were used. Each railway had dozens of tugs and the harbor was a hive of activity. New York was also a busy international port with large ocean ships docking, which needed 'ship assist' tugs to aid in berthing. A ship as large as the RMS Queen Mary needed many tugs. Passenger ferries to Brooklyn, New Jersey, Staten Island and Long Island, however, didn't need tugs.

The Port of New York was really eleven ports in one. It boasted a developed shoreline of over 650 miles (1,050 km) comprising the waterfronts of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island as well as the New Jersey shoreline from Perth Amboy to Elizabeth, Bayonne, Newark, Jersey City, Hoboken and Weehawken. The Port of New York included some 1,800 docks, piers, and wharves of every conceivable size, condition, and state of repair. Some 750 were classified as "active" and 200 were able to berth 425 ocean-going vessels simultaneously in addition to the 600 able to anchor in the harbor. These docks and piers gave access to 1,100 warehouses containing some 41,000,000 square feet (3,800,000 m2) of inclosed storage space. In addition, the Port of New York had thirty-nine active shipyards, not including the huge New York Naval Shipyard on the Brooklyn side of the East River. These facilities included nine big ship repair yards, thirty-six large dry-docks, twenty-five small shipyards, thirty-three locomotive and gantry cranes of fifty ton lift capacity or greater, five floating derricks, and more than one hundred tractor cranes. Over 575 tugboats worked the Port of New York.[1]

The Brooklyn Navy Yard had its own fleet of tugs to handle its own products as well as dozens of other naval vessels visiting the harbor. The New York City Department of Sanitation had tugs to move trash—city garbarge was collected by carts and loaded on slips onto barges, from there it was towed several miles out to sea and dumped into the Atlantic Ocean. Later it was moved to garbage dumps, the last largest being the Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island.

Later history

In 1946 a tugboat strike seriously impaired the operations of the port.[2]

New York City developed its own style of tugboat. The vessels had tall, narrow houses, with high pilothouses to aid in seeing over the tops of railroad boxcars on carfloat barges towed alongside "on the hip". Machinery was unique among marine steam engines in that many compound steam engines were non-condensing and exhausted to the air. The New York Central tug 16 had a single-cylinder non-condensing engine. Old films of the harbor exhibit puffs of steam as the tugs make their journey. This feature was unique in tug marine architecture. Hulls were usually iron or steel and boilers were fired with Appalachian anthracite coal.

In the last half of the 20th century, trade moved to cars, trucks and airplanes. Railroads went bankrupt, new tugboats used diesel engines, and not one of the hundreds of New York City steam tugs built still serve the harbor.

Incidents

Tugs were involved in several incidents in the harbor including the Black Tom explosion where German saboteurs blew up an ammunition pier in 1916; and another, in 1943, when a munition ship SS El Estero caught fire in the harbor with almost 1400 tons of TNT aboard. German U-boats prowled near the harbor of New York (U-123), and the USS Turner (DD-648) sank after an internal explosion in January 1944. Over the years there were many marine boiler explosion including the ferry Westfield in 1871.

See also

- Binghamton (ferryboat)

- Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal

- Catawissa (tugboat)

- Chemical Coast

- History of New York City transportation

- Hoboken, New Jersey

- List of ferries across the Hudson River to New York City

- Mobro 4000

- New York Central Tugboat 13

- New York Central Tugboat 16

- New York Tugboat Race

- North River piers

- North River Tunnels

- Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

- Port of New York and New Jersey

- Standard Oil Company No. 16 (harbor tug)

- Staten Island Ferry

- Tugboat Annie

- Weehawken, New Jersey

References

- Life Magazine, Nov 1944

- New York Tugboat strike