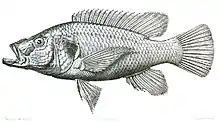

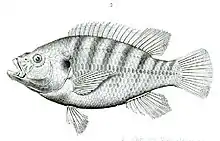

Tristramella simonis

Tristramella simonis, the short jaw tristramella, is a vulnerable species of cichlid fish from the Jordan River system, including Lake Tiberias (Kinneret), in Israel and Syria, with introduced populations in the Nahr al-Kabir and Orontes basins in Syria.[1][2] It prefers waters with little or no movement.[2] Along with other tilapias, T. simonis is commonly caught as a food fish in parts of its range and it is commercially important in Lake Tiberias.[1][3]

| Tristramella simonis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration from Poissons et Reptiles du lac de Tibériade et de quelques autres parties de la Syrie (Lortet, 1883) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cichliformes |

| Family: | Cichlidae |

| Genus: | Tristramella |

| Species: | T. simonis |

| Binomial name | |

| Tristramella simonis (Günther, 1864) | |

| Synonyms | |

Conservation status and taxonomy

It is the only member of the genus Tristramella that remains extant,[2] but it is vulnerable according to the IUCN.[1] Primary threats are water extraction and climate change reducing the rain in its range.[1] Other potential threats are uncontrolled fishing,[1] and outbreaks of a viral disease that causes blindness in tilapia, including T. simonis.[3] The species survives in less than ten locations. The primary location is Lake Tiberias where it remained common, the population was not threatened and fisheries are well-controlled (unlike other parts of its range).[1] However, in a review of catches in Lake Tiberias, a strong and serious decline was observed in 2006–2016 compared to 1996–2005, which was even more extreme if compared to 1986–1995. If looking at each year in 2000–2015, there was a sudden strong decline to very low levels in 2005–2006, with a slight rebound in 2010, then followed by very low levels again. It likely has the potential to rebound, as small juveniles are still common.[4] Two northern populations, intermidia from Lake Hula and magdelainea from the vicinity of Damascus, are extinct,[5][6] but their taxonomic status is uncertain.[2] In the past, they were recognized as subspecies of T. simonis by FishBase and they are still recognized as valid, separate species by the IUCN, which however has not reviewed their status since 2006.[5][6] Today FishBase and Catalog of Fishes consider both intermidia and magdelainea as synonyms of T. simonis.[7][8]

In contrast to the conservation status in much of its native range, a survey in Syria in 2008 found that T. simonis had been introduced to the Nahr al-Kabir and Orontes basins. It was abundant at some of these locations, even thriving in man-made habitats like reservoirs.[2]

Appearance and behavior

This species can reach a total length of 25.8 cm (10.2 in),[11] but adults typically are 18–21 cm (7–8.5 in).[9] It resembles a typical tilapia, usually being overall olive–brownish to golden–brownish, sometimes with a banded pattern. Compared to the extinct T. sacra, T. simonis has a proportionally shorter head and its lower jaw at most protrudes slightly past the upper jaw.[9][10] They also differ in their teeth (number and shape) and certain meristics.[10][11] If recognized as valid, the extinct intermidia and magdelainea only differ slightly in proportions and other details compared to T. simonis.[9][10]

T. simonis mostly feeds on phytoplankton and macrophytes, but also takes zooplankton and small benthic invertebrates.[9][12] In Lake Tiberias, adults are found in open-water schools for much of the year, while the young live in sheltered habitats near the coast.[3] The species can reach maturity when 16 cm (6.5 in) long,[9] and breeding is from March to August, with a female being able to spawn two or three times in a season.[12] It is a mouthbrooder, but some sources indicate this only is done by the female,[1][9] while others indicate it is done by both parents.[12] There are up to 250 relatively large eggs,[9] which are laid on the open bottom in a "nest" in water less than 3 m (10 ft) deep.[4] Shortly after they are picked up in the parent's mouth. The juveniles stay in the mouth after they hatch from the eggs, only leaving their parent when they reach about 1.4 cm (0.55 in).[9]

Although hybrids are well-known among tilapias, hybrids between Tristramella and other tilapias are unknown. Despite both living in Lake Tiberias and them being close relatives, hybridization between T. simonis and the now-extinct T. sacra also is not known to have occurred.[11] A species of fish louse, Argulus tristramellae, apparently is host specific, only parasitizing T. simonis (even when still common, T. sacra was not attacked by this fish louse).[11]

References

- Goren, M (2014). "Tristramella simonis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T61362A19010371. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T61362A19010371.en.

- Borkenhagen, K.; J. Freyhof (2009). "New records of the Levantine endemic cichlid Tristramella simonis from Syria". Cybium. 33 (4): 335–336.

- Gophen, M. (2018). Ecological Research in the Lake Kinneret and Hula Valley (Israel) Ecosystems. pp. 10–11, 234, 247–248.

- Gophen, S. (2017), Ecological Dynamics in the Kinneret Littoral Ecosystem

- Goren, M. (2006). "Tristramella intermedia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006: e.T60792A12399367. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2006.RLTS.T60792A12399367.en.

- Goren, M. (2006). "Tristramella magdelainae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006: e.T61365A12468486. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2006.RLTS.T61365A12468486.en.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2019). Species of Tristramella in FishBase. November 2019 version.

- Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Species in the genus Tristramella". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Serruya, C., ed. (1978). Lake Kinneret. Dr. W. Junk bv Publishers, The Hague–Boston–London. pp. 420–424. ISBN 978-94-009-9954-1.

- Steinitz, H.; A. Ben-Tuvia (1960). "The Cichlid fishes of the genus Tristramella Trewavas". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13. 27 (3): 161–175. doi:10.1080/00222936008650912.

- Kornfield, I.L.; U. Ritte; C. Richler; J. Wahrman (1979). "Biochemical and Cytological Differentiation Among Cichlid Fishes of the Sea of Galilee". Evolution. 33 (1): 1–14. doi:10.2307/2407360. JSTOR 2407360.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2019). "Tristramella simonis" in FishBase. November 2019 version.