Tripartite alignment

In linguistic typology, tripartite alignment is a type of morphosyntactic alignment in which the main argument ('subject') of an intransitive verb, the agent argument ('subject') of a transitive verb, and the patient argument ('direct object') of a transitive verb are each treated distinctly in the grammatical system of a language.[1] This is in contrast with nominative-accusative and ergative-absolutive alignment languages, in which the argument of an intransitive verb patterns with either the agent argument of the transitive (in accusative languages) or with the patient argument of the transitive (in ergative languages). Thus, whereas in English, "she" in "she runs" patterns with "she" in "she finds it", and an ergative language would pattern "she" in "she runs" with "her" in "he likes her", a tripartite language would treat the "she" in "she runs" as morphologically and/or syntactically distinct from either argument in "he likes her".

| Linguistic typology |

|---|

| Morphological |

| Morphosyntactic |

| Word order |

| Lexicon |

Which languages constitute genuine examples of a tripartite case alignment is a matter of debate;[2] however, Wangkumara, Nez Perce, Ainu, Vakh dialects of Khanty, Semelai, Kalaw Lagaw Ya, Kham, and Yazghulami have all been claimed to demonstrate tripartite structure in at least some part of their grammar.[3][4][5][6] While tripartite alignments are rare in natural languages,[1] they have proven popular in constructed languages, notably the Na'vi language featured in 2009's Avatar.

In languages with morphological case, a tritransitive alignment typically marks the agent argument of a transitive verb with an ergative case, the patient argument of a transitive verb with the accusative case, and the argument of an intransitive verb with an intransitive case.

Tripartite, Ergative and Accusative systems

A tripartite language does not maintain any syntactic or morphological equivalence (such as word order or grammatical case) between the core argument of intransitive verbs and either core argument of transitive verbs. In full tripartite alignment systems, this entails the agent argument of intransitive verbs always being treated differently from each of the core arguments of transitive verbs, whereas for mixed system intransitive alignment systems this may only entail that certain classes of noun are treated differently between these syntactic positions.[1]

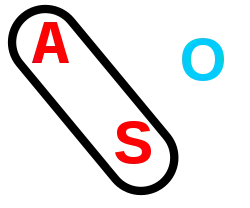

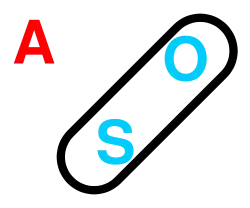

The arguments of a verb are usually symbolized as follows:

- A = 'agent' argument of a transitive verb (traditional transitive subject)

- O = 'patient' argument of a transitive verb (traditional transitive object)

- S = argument of an intransitive verb (traditional intransitive subject)

The relationship between accusative, ergative, and tripartite alignments can be schematically represented as follows:

| Ergative-Absolutive | Nominative-Accusative | Tripartite | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | ERG | NOM | ERG |

| O | ABS | ACC | ACC |

| S | ABS | NOM | INTR |

See morphosyntactic alignment for a more technical explanation.

The term 'subject' has been found to be problematic when applied to languages which have any morphosyntactic alignment other than nominative-accusative, and hence, reference to the 'agent' argument of transitive sentences is preferred to the term 'subject'.[7]

Types of tripartite systems

Languages may be designated as tripartite languages in virtue of having either a full tripartite morphosyntactic alignment, or in virtue of having a mixed system which results in tripartite treatment of one or more specific classes of nouns.[1]

Full tripartite systems

A full tripartite system distinguishes between S, A and O arguments in all classes of nominals.[1] It has been claimed that Wangkumara has the only recorded full tripartite alignment system.[3][8][1]

Example

Wangkumara consistently differentiates marking on S, A, and O arguments in the morphology, as demonstrated in example (1) below:[9]

(1) Wangkumara a. karn-ia yanthagaria makurr-anrru man-NOM walk.PRES stick-INSTR 'The man walks with a stick.' b. karna-ulu kalkanga thithi-nhanha man-ERG hit.PAST dog-ACC.NONM.SG 'The man hit the (female) dog.'

In the above example, the intransitive case in (a) is glossed NOM, in accordance with Breen's original transcription. Across (1), we see differential case suffixes for each of intranstive (NOM), ergative (ERG), and accusative (ACC) case.[10]

The same tripartite distinction is clear in the pronominal system:[11]

Palu-nga nganyi die-PAST 1sg.NOM "I died." Ngkatu nhanha kalka-nga 1sg.ERG 3sg.ABS hit-PAST "I hit him/her." Nulu nganha kalka-ng 3sg.ERG 1sg.ABS hit-PAST "S/he hit me."

In the above examples, we see the first person singular pronoun taking different forms for each of the S, A, and O arguments (marked NOM, ERG and ABS respectively), indicating the tripartite alignment in pronominal morphology.

Syntactic surveys of Wangkumara suggest this is generally true of the language as a whole.[3] Hence, Wangkumara represents a case of a full tripartite alignment.

Mixed systems

More common than full tripartite systems, mixed system tripartite alignments either demonstrate tripartite alignment in some subsection of the grammar, or else lacks the ergative, the accusative, or both in some classes of nominals.[1] An example of the former kind of mixed system may be Yazghulami, which exhibits tripartite alignment but only in the past tense.[6] An example of the latter would be Nez Perce, which lacks ergative marking in the first and second person.[1]

The following examples from Nez Perce illustrate the intransitive-ergative-accusative opposition that holds in the third person:[12]

(2) Nez Perce a. Hi-páay-na háama-Ø 3SG-arrive-PERF man.NOM 'The man arrived.' b. Háamap-im 'áayato-na pée-'nehne-ne man-ERG woman-ACC 3SG-3SG-take-PERF 'The man took the woman away.'

In the above examples, (2a) demonstrates the intranstive case marking (here coded as NOM), while (2b) demonstrates differential ergative and accusative markings. Thus, Nez Perce demonstrates tripartite differentiations in its third person morphology.

Realizations of tripartite alignment

Passive and anti-passive constructions

Ainu also shows the passive voice formation typical of nominative-accusative languages and the antipassive of ergative-absolutive languages. Like Nez Percé, the use of both the passive and antipassive is a trait of a tripartite language.

Distribution of tripartite alignments

References

- Blake, Barry J. (2001). Case. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 125. ISBN 9780521807616.

- Baker, Mark (2015). Case. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 1107055229.

- Breen, J. G. (1976). 'Ergative, locative, and instrumental case inflections - Wangkumara', in Dixon, R.M. (ed.), Grammatical Categories in Australian Languages. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, pp. 336-339.

- Rude, N. (1985). Studies in Nez Perce grammar and discourse. University of Oregon: doctoral dissertation.

- Watters, D. E. (2002). A Grammar of Kham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 69.

- Dixon, R.M.W. (1994). Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 40.

- Falk, Y. N. (2006). Subjects and Universal Grammar: An explanatory theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1139458566.

- McDonald, M.; Wurm, S. A. (1979). Basic materials in Wankumara (Galali): Grammar, sentences, and vocabulary. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Wangkumara examples from Breen, 1976: 337-338.

- Siewierska, Anna. (1997). 'The formal realization of case and agreement marking: A functional perspective', in Simon-Vandenberg, A.M., Kristin Davidse, and Dirk Noel (eds.), Reconnecting Language: Morphology and Syntax in Functional Perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, p.184

- Siewierska, Anna (2004). Person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 55.

- Nez Perce examples from Rude, 1985: 83, 228.

Bibliography

- Blake, Barry J. (2001). Case. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nicole Kruspe, 2004. A Grammar of Semelai. Cambridge University Press.

- Nez Perce Verb Morphology

- Noel Rude, 1988. Ergative, passive, and antipassive in Nez Perce. In Passive and Voice, ed. M. Shibatani, 547-560. Amsterdam: John Benjamins