Theodosia Ivie

Lady Theodosia Ivie (1628–1697) was an aristocratic heiress and a figure of notoriety in the east end of London in the 17th century.[1] Famed for her “wit, beauty and cunning in law above all others,” her claims to own land stretching from Wapping to Ratcliff[2] led to a constant stream of litigation which ran for almost 75 years.[3] At one particular trial, presided over by Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys (later called the Hanging Judge),[4] evidence emerged that Ivie had presented the court with forged deeds on which she made her land claims and Jeffreys subsequently arranged for charges to be brought against her for forgery.[5]

Land disputes

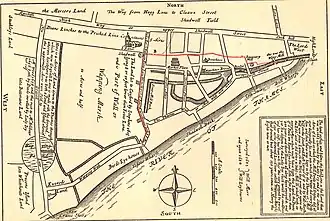

Born Theodosia Stepkin,[6] much of the ancestral land she inherited was in Wapping, on former marsh land which had been drained by the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vanderdelf. Ivie's confidence to challenge so many people over titles to land in this area rested largely on an Act of Parliament her ancestors had secured which stated the family owned: "CXXX acres, lyeing and being besydes Seynt Katheryns nygh unto the Tower of London and in the parysshe and town of Stebunhyth, which CXXX acres abutten upon the High waye ledying from London to Ratcliffe on the Northe parte and upon Thamys on the south parte, and the east part abbutyth upon the Towne of Ratcliffe".[7] It was prime land next to the River Thames and central London but, such was the rapid development in the area[8] that hamlets expanded and boundaries significantly drifted over time and hence disputes occurred. By successfully challenging both the boundaries of her land, as well as those holding land contiguous to her own, Lady Ivie built up a portfolio of properties in Wapping alone to over 800 messuages – far in excess of her original inheritance.[9]

In neighbouring Shadwell, where the projector Thomas Neale[10] had transformed the area with huge investment, Ivie claimed his entire development fell within her ancestral inheritance and succeeded in taking the land from him. Neale immediately launched a legal challenge against Lady Ivie and, in the following trial of 1684, he not only succeeded in getting his Shadwell land restored to him but, in the process, demonstrated to the court that Lady Ivie’s deeds – on which her title depended – were entirely false.[11] Two specific deeds Ivie produced were self-evidently forged as they contained elementary and irrefutable errors. For instance, the styling of her deeds of 1555 referred to Philip and Mary as being King and Queen of Spain[12] on a date before that had even happened, when Philip and Mary were still Princes of Spain only.[13] There was also a witness produced who claimed to have personally observed Lady Ivie working on the forgeries, scribing the initial, ornate opening letters on the deeds.[14] At the conclusion of the trial, after Lady Ivie lost Shadwell and faced criminal charges, she took flight, escaping to the Whitefriars liberty where she was beyond the reach of the law.[5]

Her accomplice Stephen Knowles, who inadvertently incriminated himself during the opening minutes of the trial, likewise fled, though in his case to the Liberty of the Mint in Southwark. Knowles, under close questioning from Judge Jeffreys, had wholeheartedly vouched for Ivie’s deeds and then had to watch, uncomfortably, as Ivie’s case unravelled before him as those same deeds were dramatically exposed as forgeries.[5] Eventually, Lady Ivie (though not Knowles) came out of the liberty and she immediately set about pacifying her anxious creditors and tenants by publishing a document clarifying her land holding titles.[5] The law quickly caught up with her and she was charged and faced a trial for forgery.[15] The verdict of the trial was a surprise, in one sense, because her deeds were obviously false, but she was found not guilty because it was impossible to bring the crime home to her personally.[16] Afterall, any one of her ancestors could, in theory at least, have created the false deeds and she had simply taken them at face value. Only after Ivie’s not guilty verdict did Knowles leave the Mint. He was in no hurry to leave as, throughout his time there, he had been living with his family who had joined him and his accommodation was being paid for by Lady Ivie.[5]

The contest over Shadwell was the culmination of years of land disputes in Wapping between Ivie and Thomas Neale – Neale having interests in both parishes. Though Ivie did properly inherit many properties and parcels of land in Wapping, the disputes usually occurred with those holding land bordering hers – where there could be some argument about precise boundaries. Vague descriptions in old deeds, or the loss or moving of boundary markers over the years, meant constant challenges and disputes. In 1677 there was such a dispute over 22 acres of land, all of which Ivie claimed was hers by inheritance. The land was held by a certain Mr Bateman and, rather than go to court to challenge the title in the conventional manner, Lady Ivie purchased the lease on five acres of the disputed land via a third party and then simply held on to the land after the lease expired. The onus was then on the land owners to try and evict her. Having secured five acres, she then challenged for the remainder.[17] Her opponents were called Bateman’s Creditors (and included Thomas Neale). One particular creditor was Sir John Ireton[18] – an eminent alderman, former Mayor of London and brother of the regicide, Henry Ireton (son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell). Ireton engaged a solicitor called George Johnson who was tasked with exposing the key lease Lady Ivie relied on to make her title claims (Glover’s Lease) as fraudulent. That was no easy task when the lease had been endorsed by Sir John Bramston the Elder – former Lord Chief Justice of England[19] - who happened to be Lady Ivie’s great-uncle and protector of her family.

Johnson subornation

Accounts vary as to what happened next. Lady Ivie claimed that solicitor Johnson offered £500 to anyone who had evidence that her deed was forged. When she discovered this, Ivie brought his fraudulent actions to the attention of the authorities and he was subsequently charged with subornation of perjury. At least two trials took place on aspects of his subornation: the first was King v Johnson which took place at the Guildhall in 1677-78 Hilary term, when Johnson was found guilty.[20] The second trial was held two years later in 1679 where not only was Johnson was found guilty again, but he was also struck off the attorneys' roll, fined 45 marks and forced to enter into sureties against his future good behaviour. Lady Ivie’s opponents interpreted events differently. Though they could not deny that Johnson had, indeed, been guilty of subornation, they believed that Ivie had enticed Johnson into entrapment. This is quite a compelling argument when it is considered that the person Johnson was liaising with and who gave him a confession that he had been forging for Ivie was her very own accomplice Thomas Duffett.[21] Duffett was the first of Ivie’s two accomplices. After confessing to forging, Duffett mysteriously vanished and gave no evidence against Ivie at Johnson’s trials.[5] Her opponents claimed that Johnson was devastated by these verdicts against him as, now his career was over, his spirits sank low and he faded away, dying shortly afterwards. From Lady Ivie’s point of view, however, Johnson was justly punished by the courts for breaking the law.

Salkeld mortgage

Thomas Duffett’s confession to forging documents for Lady Ivie throws light on an earlier incident of false documents which occurred in 1670. Ivie was living in the household of one of her trustees, Sir William Salkeld, a man who happened to die shortly after her arrival. Ivie then proceeded to present Salkeld’s widow with a mortgage deed for £1,500 and claimed the Salkeld house was now hers. Not only was her claim vehemently rejected by the Salkeld family but also another distinguished person residing there – Sir Charles Cotterell, Master of Ceremonies to both King Charles I and II. Cotterell later gave evidence against Lady Ivie in the 1684 trial where she was charged with forgery. The uproar which followed was only quelled when Lady Ivie surrendered her supposed mortgage to the Salkeld’s daughter, Lucy. Lady Ivie only escaped forgery charges by further conciliatory action by another of her trustees, Colonel Edward Grosvenor, who was obliged to enter into a £1,000 surety bond for Lady Ivie’s future good behaviour, and an assurance that she would never again meddle in the Salkeld family’s affairs. Grosvenor also acted as arbitrator in Ivie’s matrimonial separation from her husband. It is significant to note that the person Ivie surrendered the false mortgage to, Lucy Salkeld, was the wife of Ivie’s accomplice, Thomas Duffett. The Duffetts would later separate before Thomas fled the country to escape justice.[22] The quid pro quo between Ivie and Duffett was that, in return for Ivie promoting his career as a playwright,[23] he wrote out and altered deeds to help her win title claims.[5] Critics have not been kind to his writing. The Dictionary of National Biography entry for Thomas Duffett calls him a “dramatist … who unfortunately took to play-writing … as literature, his productions are beneath criticism”. Duffett’s plays were bawdy burlesque, which was popular at the time, but the language used was sometimes so offensive that some audience members walked out during performances.[24]

Family

Lady Ivie was the direct descendant of Thomas Stepkyn[25] and Macheline c. 1510-67 – German immigrants who settled at the Wapping Marshes in lower Whitechapel. Stepkyn was the King’s beer maker[26] and had a lucrative role supplying the Navy from his home/business at the Hermitage (or Swansnest)[27] just east of the Tower of London. With increasing prosperity, Stepkyn acquired many hundreds of acres of land from the nearby Cistercian Abbey of St Mary Graces, as well as from the Lord of the Manor (Baron Wentworth) and the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral. These free, lease and copyhold lands were eventually to become Lady Ivie’s inheritance and the subject of her litigation. Part of the area was later demolished and redeveloped into St Katharine Docks. Lady Ivie’s mother was Judith Atwood 1605-34 (daughter of Dr Thomas Atwood, a renowned oculist of Worcester) and her father was John Stepkin 1605-52, was a Catholic Royalist and oculist to King Charles I and his wife. Lady Ivie had two brothers and she only became her father’s heir after one brother died and the second was disinherited by the father. After her mother’s death when she was young, Ivie’s welfare was in the hands of an assortment of female relations who would have tried to instil in her the expectation that she would be obedient and compliant – to defer to male relations in business matters.[28] From her Bramston relations, she acquired knowledge of the law and from the Atwoods, knowledge of eye care.[29]

Lady Ivie married at least three times: firstly, to George Garratt (son of Sir George Garratt) in 1647; secondly to Thomas Ivie (later knighted) in 1649 and, finally, to James Bryan in 1674. Thomas Ivie, before meeting Theodosia, had been an agent for the East India Company in Madras.[30] With George Garratt, she had one son (George 1647-67)[31] and with Thomas Ivie, she had one daughter (Theodosia 1661-68). Also, she had a step-daughter from her marriage to James Bryan (Frances Bryan b.1666 – married to Sir Robert Clerke). Lady Ivie outlived all her husbands and her biological children. Lady Ivie’s grandmother was Mary Bramston, daughter of John Bramston the Elder – Lord Chancellor of England in 1635. The Bramstons of Skreens in Essex[32] took an active role in supporting their Stepkin relations – acting as trustees for the Stepkin estate, giving pivotal and authoritative testimony in support of both Lady Ivie and her father in their legal battles.

Alimony battle

Alimony was a new notion, only becoming law on 22 June 1649[33] and so, long before she became engulfed in high-profile land disputes, Lady Ivie had already gained notoriety when details of her tortuous marriage, and a novel attempt to extract alimony, became public knowledge.[34] Husband and wife fought each other, fought each other’s relatives, fought each other’s trustees and friends, through every type of court at their disposal: Court of Chancery, Court of King's Bench, Court of Equity, Ecclesiastical Court and the Arches Court. Often cases overlapped and conflicted with one other.[35] Eventually, the estranged husband, Sir Thomas Ivie, submitted an appeal to the highest authority in the land, the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, and begged him to overturn his wife’s alimony award.[36] He failed. Thomas Ivie’s family hailed from Malmesbury in Wiltshire and the antiquarian John Aubrey attended school at Malmesbury and knew the family well. Aubrey came to read a copy of Ivie’s Appeal to Cromwell and said it contained “As much baudry and beastliness as can be imagined”.[37] Lady Ivie had, earlier, tried to extract matrimonial compensation from the family of her first husband. When she was just 20 years old she petitioned (through her father John Stepkin) the House of Lords following the death of her husband George Garrett. Ivie claimed her husband’s family had promised her an estate for her widowhood. She failed, though her infant son was granted an annuity.[38]

Personal

Like her father and grandfather, Lady Ivie was renowned for skill in healing eye problems. She also had a close interest in theatre and was related to William Killigrew[39] and his son Robert (William’s brother Thomas ran the King’s Playhouse on Drury Lane). Both William and Robert acted as trustees for Lady Ivie’s estate.[40] She had a keen interest in mystical matters and regularly consulted with fortune-tellers. She was called “The Catholic Patroness of alchemy”[41] and owned a bezoar, a stone thought to have magical healing properties, including being an antidote to poison.[42] In addition to land and property acquisitions, Ivie dabbled in a range of business ventures including paper-making and salvaging shipwrecks for treasure. She was also sufficiently acquainted with both King James II and the great Quaker, William Penn, to act as liaison between them and her friend Goodwin Wharton, who needed access to the King to get his permission for his treasure-hunting voyage to a wreck in Jersey in 1688.[43] Ivie invested £300[44] in the scheme, which failed, however, to find any trove.

Portrayal in fiction

The Victorian fiction writer M. R. James wrote "A Neighbour’s Landmark", published 17 March 1924 in the magazine The Eton Chronicle, which was based on Lady Ivie. She was depicted as a wailing ghost, eternally tormented by her theft of neighbouring land from some orphaned children. In 1659 – at the time when her alimony battle was raging, a comedy play appeared called ‘Lady Alimony, or, The Alimony Lady’ which was fortuitous. It was anonymous in origin and quite likely based on Lady Ivie herself. There are reasons for believing that Thomas Duffett made reference to the Ivies in at least one of the early plays he wrote: ‘The Amorous Old Woman: or, tis well if it takes’ concerns an heiress having a stump (wooden leg). Lady Ivie, of course, was significantly older than Duffett and Sir Thomas Ivie’s first wife was from the Stump family of Wiltshire. In a similar vein, a comedy written in 1676 by Thomas Rawlins called “Tom Essence, or, The Modish Wife” seems to parody our principal characters. Lead character Tom Essence was a perfume seller and milliner of New Exchange – exactly as Thomas Duffett had been (he too had been a milliner of New Exchange) and two ladies were fighting over this man. The two characters were named Theodosia and Lucy in the play. Lady Theodosia Ivie and Duffett’s wife Lucy Duffett/Salkeld were rivals for Thomas Duffett’s affections at the time.[45]

Downfall

As the 1680s progressed, Lady Ivie’s fortunes began to spiral downwards. The loss of Shadwell (and the credit such an acquisition had briefly brought), her absence in a liberty for so long and the serious nature of the charges against her had unnerved her many creditors. She also suffered significant losses during the Wapping Fire of 1682[46] and had, briefly, fled overseas at the Glorious Revolution in 1688, though she returned a few weeks later only to find bailiffs waiting who narrowly missed seizing her person and had to satisfy themselves by taking all her personal possessions.[47] It made no difference that the trial verdict was ‘not guilty’ because her opponents now gained momentum against her and began to overwhelm her with litigation and challenges to all her land titles. Ivie began losing her remaining Wapping properties in such a rapid succession that, by the time of her death, her one solitary property in Wapping was on the point of being taken from her as Thomas Neale declared her in contempt because she had failed to return papers to the court. With her death ended five generations of Stepkin descendants holding prime Wapping land.[48] None of the bequests in her will were able to be met and the majority of her numerous creditors received nothing from her estate; the legal battles continued for 30 years after her demise.

References

- Proudler, Karen (24 June 2018). Lady Ivie: Queen of Wapping. KP Publishing. ISBN 9781911472063.

- Description by her opponent Thomas Neale in a pamphlet he published immediately after her death: ‘The Famous Tryal in B.R. between Thomas Neale Esq and the late Lady Theodosia Ivy, the 4th June [sic 3rd] before the Right Honourable the Late Lord Jeffreys, Lord Chief Justice of England for part of Shadwell in the county of Middlesex. As also the Title of the Creditors of Sir Anthony Bateman and the Heirs of Whichcott, compared with that of the Lady Ivy to certain lands in Wapping’ together with a pamphlet heretofore writ and set out by Sir Thomas Ivy (her husband) himself and here now reprinted again. In Perpetuam Rei Memoriam. 1696. London Metropolitan Archives: LMA: ACC/0445/001 Ivy Family. Note: the first pamphlet mentions a trial date of 4th June whereas, in fact, it was 3rd; the second pamphlet by the heirs of Whichcote was dated 1687 and the final pamphlet by Sir Thomas Ivie was dated 1655

- Litigation ran from 9 Oct 1648 House of Lords HL/PO/JO/10/1/275 to 1723 ACC/0445/002 Legal Case before the Master of the Rolls, LMA, Ivy Family/Personal Records

- Sequence of trials was: Baron v Witwrod in 1682 which Lady Ivie lost (Witwrod being one of her tenants). Ivie retaliated by bringing an Action of Ejectment (Alcock versus Baron) at Easter 1683 where she won all of Thomas Neale’s Shadwell lands. Neale immediately retaliated by bringing the second trial Mossam versus Ivie (Mossam being Neale’s proxy/tenant). Only this last trial has been preserved in verbatim as it took place at the King’s Bench. A full transcript is available in ASIN-B00086B21W ‘The Lady Ivie’s Trial, for great part of Shadwell in the county of Middlesex before Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys in 1684’, Sir John Fox, published by Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1929.

- Proudler, Karen (2018). Lady Ivie's Audacious Quest for Shadwell. KP Publishing. p. 280-282. ISBN 9781911472100.

- The Stepkin Family of Tudor London ISBN 978-1-911472-09-4, Karen Proudler, 2018

- The National Archives TNA: C 89/1/12 dated 5 Nov 1565. An Act for the assurance of the moiety of 130 acres of land lying by St Katherine’s near the Tower of London to Richard Hill, being formerly sold to him by Cornelius Vanderdelf. Act 27, Hen VIII, c1535 Parliamentary Archives: HL/PO/PB/1/1535/27 H8n51 and HL/PO/PU/1/1535/27 H8n51

- Wapping 1600-1800: a social history of an early Modern London suburb, ELHS, 2009. Also, Dr Michael J. Powers 1971 PhD dissertation The Urban Development of East London 1550-1700

- Lady Theodosia IVIE (1696). Begin. The Lady Ivy, etc. [A statement by the creditors of Sir Anthony Bateman and the heirs of Rebecca Whichcot in support of their claims to land in the possession of Lady Ivie. With a plan.]. pp. 1–9.

- J.H. Thomas ‘Thomas Neale, a seventeenth century projector’ PhD dissertation, University of Southampton, 1979. Also, The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1660-90: Introductory Survey, Appendices, Constituences, members A – B, Basil Duke Henning, 1983. Also, Thomas Levensen ‘Newton and the Counterfeiter’, p136

- William Cobbett (1811). Cobbett's Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason. R. Bagshaw. p. 555.

- ‘Renuncia de Carlos V en favor de Filip II de los reinos de Castilla’ pp 511-513 by E. Simancas

- ‘A Compendium of the Law of Evidence’ by Thomas Peake, Serjeant-at-Law, 1802

- Lucy Salkeld/Duffett was the witness, cited in Lady Ivy’s Trial, for Great Part of Shadwell in the County of Middlesex, Die Martis, 3 Junii 1684. Ter. Trin 36 Car II. B.R. Elam Mossam (Plaintiff) versus Dame Theodosia Ivy (Defendant)

- Six Criminal Women by Elizabeth Jenkins, 1949 ISBN 978-0836980691

- In respect of Theodosia Bryan alias Ivy, Records of the Court of King’s Bench, University of Houston ref KB29/345 “The jurors at the bar say that she is not guilty …”

- Lady Ivie: Queen of Wapping, 2018, Karen Proudler ISBN 978-1-911472-06-3

- Gentlemans Magazine Dec. 1837, Sylvanus Urban

- In Sir John Bramston (junior)’s autobiography he stated “The Lady Ivie was sued ….. in which the validity of Glover’s lease was the maine question; to which my father’s name and Richard Archbold’s name were endorsed as witnesses” The Autobiography of Sir John Bramston K.B. of Skreens in the Hundred of Chelmsford. Camden Society, 1845. ISBN 978-551-918-5776

- Report of Cases Adjudged in the Court of King’s Bench, during the reigns of Charles II, James II and William III. Vol II, 1794 by Bartholomew Shower

- Calendar of State Papers: CSPD, Car II, 393, No. 112 letter from Sir Robert Cotton to the King asking for a pardon for Thomas Duffett who had confessed to forging, so he could give evidence against Lady Ivie. CSPD.

- Calendar of State Papers: CSPD, Car II, 393, No. 112 letter from Sir Robert Cotton to the King asking for a pardon for Thomas Duffett who had confessed to forging, so he could give evidence against Lady Ivie. CSPD, Car II, Vol 19, 1677-78, CSPD, Car II, 393, No. 112. W. Jones, 7 May 1677. Also, Lambeth Palace Library divorce records: LPL: CA, Case 2891 (1676) Eee6, f93v-94r and LPL: E 5/101 Duffett v Duffett, 1676

- The influence of English Colonial Discourse on Early Irish Adaptations of Shakespeare 1674-1754 by Liam O’Down, 2011. National University of Ireland, Maynooth, discusses Duffett’s influence on English/Irish relations. Also, see Frederick James Furnival’s Fresh Allusions to Shakespeare from 1594 to 1694 p242. 1886,

- Cited by Gerard Langborn of one of Duffett’s plays in Dublin

- The Stepkin Family of Tudor London ISBN 978-1-911472-09-4, Karen Proudler, 2018 c1500-54

- TNA: C 1/675/14 Stepkyn v Bayly 1529-32 refers to Stepkin’s occupation

- TNA: MPB 1/4/1 Plan of The Hermitage, dated 1590. Also, an article from The Copartnership Herald, Vol II, 19 (September 1932), “Stepney in other days” by Sydney Maddocks describes the Stepkin home as “the King’s brewhouse on the east of St Katherine’s stood at a place which bore the name of The Hermitage”. Also, LMA: Q/HAL/283, 1665 lease of The Hermitage/Swansnest. Also, Tower Hamlets LHL: P/SLC/2/16/48/1, Lady Ivie’s Lease of The Hermitage, 1651

- Pollock, Linda (August 1989). "'Teach her to live under obedience': the making of women in the upper ranks of early modern England". Continuity and Change. 4 (2): 231–258. doi:10.1017/S0268416000003672. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Female Education in the late 16th and Early 17th Centuries in England a Wales: a study of attitudes and practices. 1996, PhD dissertation, Caroline Mary Kynaston. Bowden University of London

- IRS: Vestiges of Old Madras 1640-1800, Vol. 1, p. 63, Henry Davidson Love

- TNA: PROB 11/324 Will of George Garrett, 1667

- The Autobiography of Sir John Bramston K.B. of Skreens in the Hundred of Chelmsford. Camden Society, 1845. ISBN 978-551-918-5776

- The Historical Background of Alimony and its Present Statutory Structure by Chester G. Vernier and John B. Hurlbut. 1939

- Lady Ivie: Queen of Wapping ISBN 978-1-911472-06-3 by Karen Proudler, 2018. See also TNA: C78/532 Theodosia Ivy v Thomas Ivy ref alimony, 12 Nov 1655; TNA: C10/13/63 Ivy v Stepkin, 1651 and TNA: E 214/527 Stepkin – Ivie – Bramston marriage settlement, dated 1650

- TNA: C 6/52/47 Ivie v Bramston; TNA: C5/434/78 Ivy v Bramston, 1652; TNA: C 5/394/29 Crowder v Ivye, 1652; Essex Record Office ERO: D/Deb/1/6 – Agreement T Ivie/EIC and Bramston, 1650; TNA: C10/13/64 Ivy v Stepkin, 1651

- Alimony Arraign’d, or, the Remonstrance and Humble Appeal of Thomas Ivie Esq from the High Court of Chancery to his Highness the Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland wherein are set forth the unheard of Practices and Villainies of Lewd and Defamed Women in order to Separate Man and Wife, 1654. Also, House of Lords Journal, Vol 6, Alimony, 23rd May 1649 and TNA: C7/416/54 Grosvenor v Ivie, 1655 and TNA: C6/52/47 Ivie v Bramston, 1671

- Bodleian Library: Aubrey 12, pp238-239

- House of Lords Journal: Vol 10: 10th Oct 1648, pp534-54, Garrett’s Cause

- William Killigrew’s wife was Mary Hill, related to the Moundford Hills (including Richard/Jasper) who married the Bramstons – Mary Moundford was instrumental in raising Lady Ivie for some years

- TNA: C6/47/82 Ivy v Killigrew (Sir Robert), 2nd Apr 1670

- Alchemical Poetry 1575-1700 from previously unpublished sources by Arthur & Kit Knight. Ed. By Robert M. Schuler, 1979

- Stated in Thomas Ivie’s pamphlet Alimony Arraign’d, or, the Remonstrance and Humble Appeal of Thomas Ivie Esq from the High Court of Chancery to his Highness the Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland wherein are set forth the unheard of Practices and Villainies of Lewd and Defamed Women in order to Separate Man and Wife, 1654. Also, House of Lords Journal, Vol 6, Alimony, 23rd May 1649 and TNA: C7/416/54 Grosvenor v Ivie, 1655 and TNA: C6/52/47 Ivie v Bramston, 1671

- British Library, London, Vol 1, Add. MSS 20006, fol 6 verso, The Autobiography of Goodwin Wharton 1653-1704

- The Magical Adventures of Mary Parish: the occult world of seventeenth century London by Frances Timbers, 2016, p115 (Mary Parish being Goodwin Wharton’s partner for many years)

- Lambeth Palace Library divorce records: LPL: CA, Case 2891 (1676) Eee6, f93v-94r and LPL: E 5/101 Duffett v Duffett, 1676

- Published pamphlet at the British Library G3713 “Sad and Lamentable News from Wapping, giving a true and just account of a most horrible and dreadful fire which happened on Sunday the 17th of November 1682”. J. Clarke. 1682

- British Library, London, Vol 1, Add. MSS 20006, fol 6 verso, The Autobiography of Goodwin Wharton 1653-1704

- The Stepkin Family of Tudor London, Karen Proudler, 2018, ISBN 978-1-911472-09-4