The Tale of Peter and Fevronia

The Tale of Peter and Fevronia of Murom (Russian: Повесть о Петре и Февронии Муромских, Povest o Petre i Fevronii Muromskikh) is a 16th-century Russian tale by Hermolaus-Erasmus, often referred to as a hagiography.

| |

| Author | Hermolaus-Erasmus |

|---|---|

| Original title | Повесть о Петре и Февронии Муромских |

| Translator | Serge Zenkovsky |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Tale, hagiography |

Publication date | mid-16th century |

Peter and Fevronia of Murom Prince and Princess of Murom | |

|---|---|

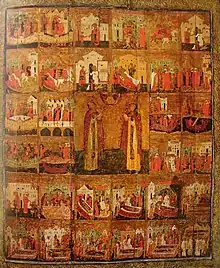

.jpg.webp) 16th century Russian Icon of Sts. Peter and Fevronia of Murom | |

| Holy Couple and Wonderworker | |

| Born | 12th century |

| Died | June 25, 1228 Murom, Russia |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodoxy |

| Canonized | 1547 by Russian Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Holy Trinity Monastery Murom, Russia |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Crown Cross Dove Monastic habit Sword |

| Patronage | Family Fidelity Love Marriage |

Plot summary

Apanage prince Paul (Russian: Павел) is much disturbed as a guileful snake has gotten into the habit of visiting his wife, disguising itself as the prince. His wife finds out that the only one who can destroy the snake, using a magiс sword, is Paul's brother, Peter (Russian: Пётр). Peter kills the snake but its blood spills over him and his body becomes covered with painful scabs. No doctors are able to help but then Peter hears of Fevronia (Russian: Феврония), a wise young peasant maiden, who promises to heal him. In reward he agrees to marry her. However, once healed he does not keep his promise but instead sends her rich gifts. Soon Peter's body is again covered with scabs. Fevronia heals him once more and this time they get married. Soon after this Prince Paul dies and Peter and Fevronia come to reign in Murom. The boyars are unhappy to have a peasant woman for princess and they ask Fevronia to leave the city, taking with her whatever riches she wants. Fevronia agrees, asking them to let her choose just one thing. The boyars find out that the wise maiden's wish is to only take her husband so Peter and Fevronia leave Murom together. Because the city no longer has a prince, a power struggle begins among the boyars, leading to havoc in Murom and finally Peter and Fevronia are asked to return. They reign wisely and happily until their last days, which they spend in separate cloisters. Knowing that they will die on the same day they ask to be buried in the same grave. The Russian Orthodox tradition does not allow for a monk and a nun to be buried together but the bodies are twice found to disappear from the original coffins and finally remain in a common grave forever.

The Text

Redactions

There exist four redactions and abundant copies of the tale, indicating the immense popularity of this piece in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Authorship

The author of the tale is Hermolaus-Erasmus (Ермолай-Еразм), who came to Moscow from Pskov in the mid 16th century to become a protopope of one of the palace cathedrals. In the 1560s he became a monk and is thought to have left Moscow. Despite the established authorship of the piece, most scholars posit that its basis lies in the oral legends of Murom.[1]

Origins

Dmitry Likhachev asserts that the story of Peter and Fevronia existed in written form already in the 15th century, before Hermolaus-Erasmus. This assertion is supported by a recorded church service from the 15th century, which praised the Murom prince Pyotr (Peter), the victor over the snake, and his young wife Fevronia with whom he was buried in the same grave. It is surmised that the main characters of the piece are historical figures. Pyotr stands for the Murom prince David Yurievich (Russian: Давид Юрьевич), who reigned in Murom but died as a monk in 1228. This prince supposedly married a peasant woman. However a lot of the details about the prince in the tale are imaginary and were created and modified over time in the oral legends of Murom.[2]

Genre and Literary Importance

The folkloric origin of this tale explains the stark differences between this work and canonical hagiographical works. In 1547 Peter and Fevronia were canonized and the tale started to be interpreted as a hagiographical piece. It was not, however, included in the Great Menaion Reader (Velikie Minei Chetii in Russian) because of its unconventional form and largely secular contents.

Soviet scholars have looked at The Tale of Peter and Fevronia as the initial stage of the secularization of Russian literature.[2] Many scholars notice the personalized nature of the piece, its focus on the life of an individual. This indicates the growing interest and attention of the society to the individual and foreshadows the development of the Enlightenment values in Russia.[3]

Folkloric Motifs

Many of the motifs found in the tale come not only from Russian folklore, but can also be found in Western European literature of the Middle Ages. The motifs of a prince's victory over a snake or dragon, his magical healing by a beautiful maiden and the motif of wise women outwitting lustful men and protecting their honor, can be seen, among others, in the Legend of Tristan and Isolde and in Boccaccio's The Decameron.

Adaptations

The Tale of Peter and Fevronia served as one of the sources to the Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov opera The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya (Russian: Сказание о невидимом граде Китеже и деве Февронии, Skazaniye o nevidimom grade Kitezhe i deve Fevronii).

Translations

An English translation is available as "Peter and Fevronia of Murom" in Medieval Russia's Epics, Chronicles and Tales by S. Zenskovsky (New York: Meridian, 1974).

References

- Kuskov, V. V. (2001). Drevnerusskie kniiezheskie zhitiia. Moskva, Krug.

- Likhachev, D. i. S. and Institut russkoi literatury (Pushkinskii dom) (1980). Istoriia russkoi literatury X-XVII i.e. desiatykh-semnadtsatykh vekov : uchebnoe posobie. Moskva, Prosveshchenie.

- R. P. Dmitrieva, Povest' o Petre i Fevronii (Leningrad: Nauka, 1979)

External links

- Full Old Russian text online http://old-russian.chat.ru/10fevron.htm