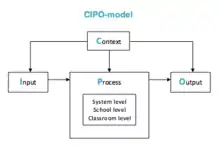

The CIPO-model

The context-input-process-output (CIPO) model is a basic systems model of school functioning, which can be applied to several levels within education, namely system level, school level and classroom level.[1] The model also functions as analytical framework through which the educational quality can be reviewed.[2]

According to his model, education can be seen as a production process, whereby input by means of a process results in output. Input, process and output are all influenced by context.[3] The context gives input, provides resources for the process and sets requirements to the output. In this way all components of the CIPO-model are interconnected to each other.

The CIPO-model is developed by Jaap Scheerens (1990).[4]

Four components

Context

Input

- Refers to the financial resources and the material infrastructure, like the school buildings and textbooks. In addition to these resources and materials, input refers to the knowledge level of students at commencement, student and teacher characteristics (like gender and ethnicities) and teachers’ qualifications.

Process

- Includes initiatives to get (desirable) output, like activities. Other process features are didactical and pedagogical approaches, school culture and school climate, peer-group processes and leadership (style).

Criticism

Existing criticism on the CIPO-model is that students are being seen as ‘raw materials’ who are ‘created’ through a production process. According to critics there is an exaggerated focus on measurable revenues. ‘Malleability’, however, is a sensitive topic with regard to systems thinking. This from systems theory derived terminology leads to resistance in educational and pedagogical communities.

However, according to others, input can be seen as children who enter school with certain characteristics. When they finish school, some characteristics will have (been) changed, more knowledge will have been acquired and new skills will have been obtained.[7]

Perspectives of quality of education

On the basis of the model’s analytical framework, five important perspectives of quality of education can be distinguished.[8]

Productivity

- From the perspective of productivity, quality of education is only assessed on the basis of revenues. The achieved results determine the extent to which education has met the expectations and thus the success of the whole system.

Effectiveness

- The effectiveness perspective focuses on context-, input- and process factors that are positively correlated to the output (revenues). The effectiveness is determined by the extent to which an education system is able to achieve predetermined goals. Like productivity, effectiveness is often expressed through student performance.

Efficiency

- This perspective seeks to achieve the highest possible effectiveness with the lowest possible of costs. This can be done in two different ways, namely achieving the same yields with fewer resources or by achieving better yields with the same resources.

Educational (in)equality

- From this perspective, quality of education is being reviewed by analysing the distribution of input, process and output (results) between different groups in education. The ideal is that all groups, like students from diverse socioeconomically backgrounds, can benefit from education equally. Academic achievement should not be, or as little as possible, the result of background factors.

Adaptivity

- The last perspective is the extent to which education adequately responds to specific questions from the broader social-, cultural- and economic context. Adaptivity can be achieved by choosing objectives that meet the expectations from society. Because of the constant changes in society and the flow of new developments this requires flexibility.

References

- Scheerens, J. (2015). School Effectiveness Research. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 21, 80-85. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.92080-4

- Cuyvers, G. (2002). Kwaliteitsontwikkeling in het onderwijs. Apeldoorn: Garant.

- Veen, H. (2015). Een brede kijk op onderwijskwaliteit: Een onderzoek naar percepties op onderwijskwaliteit binnen Stichting UN1EK. Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam.

- Scheerens, J. (1990). School Effectiveness and the Development of Process Indicators of School Functioning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 1, 61-80. doi: 10.1080/0924345900010106

- UNESCO. (2005). Understanding education quality. EFA Global Monitoring Report. Paris: Unesco.

- Onderwijsinspectie. (2010). Het CIPO-referentiekader van de onderwijsinspectie: de indicatoren, variabelen en omschrijvingen. Retrieved from http://www.onderwijsinspectie.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/CIPO_indicatoren_variabelen.pdf

- Scheerens, J. (2012). Wat is kwaliteit? In Dijkstra A. B. & Janssens F. J. G. (red) Om de kwaliteit van het onderwijs. Boom: Lemma.

- Dijkstra, A. B., & Janssens, F. J. G. (2012). Om de kwaliteit van het onderwijs: kwaliteitsbepaling en kwaliteitsbevordering. Boom: Lemma.