Terrarium

A terrarium (plural: terraria or terrariums) is usually a sealable glass container containing soil and plants, and can be opened for maintenance to access the plants inside. However, terraria can also be open to the atmosphere rather than being sealed. Terraria are often kept as decorative or ornamental items. Closed terraria create a unique environment for plant growth, as the transparent walls allow for both heat and light to enter the terrarium.

The sealed container combined with the heat entering the terrarium allows for the creation of a small scale water cycle. This happens because moisture from both the soil and plants evaporates in the elevated temperatures inside the terrarium. This water vapour then condenses on the walls of the container, and eventually falls back to the plants and soil below.

This contributes to creating an ideal environment for growing plants due to the constant supply of water, thereby preventing the plants from becoming over dry. In addition to this, the light that passes through the transparent material of the terrarium allows for the plants within to photosynthesize, a very important aspect of plant growth.

History

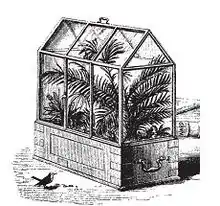

The first terrarium was developed by botanist Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward in 1842.[1] Ward had an interest in observing insect behaviour and accidentally left one of the jars unattended. A fern spore in the jar grew, germinated into a plant, and this jar resulted in the first terrarium. The trend quickly spread in the Victorian Era amongst the English. Instead of the terrarium, it was known as the Wardian case.[2]

Ward hired carpenters to build his Wardian cases to export native British plants to Sydney, Australia. After months of travel, the plants arrived well and thriving. Likewise, plants from Australia were sent to London using the same method and Ward received his Australian plants in perfect condition. His experiment indicated that plants can be sealed in without ventilation and continue thriving.[3] Wardian cases were used for many decades, by Kew Gardens and others, to ship plants around the British Empire.[4]

Types

Because of the different conditions within, terrariums can be classified into two types: closed and open.

Closed terraria

Tropical plant varieties, such as mosses, orchids, ferns, and air plants, are generally kept within closed terraria due to the conditions being similar to the humid and sheltered environment of the tropics.[1] Keeping the terrarium sealed allows for the circulation of water. The terrarium may be opened once a week to remove excess moisture from the air and walls of the container. This is done to prevent growth of mold or algae which could damage the plants and discolour the sides of the terrarium.[5] Terraria must also be watered occasionally, the absence of condensation on the walls of the terrarium or any wilting of the plants is an indicator that the terrarium requires water.[5]

Closed terraria also require a special soil mix to ensure both good growing conditions and to reduce the risks of microbial damage. A common medium used is 'peat-lite', a mixture of peat moss, vermiculite, and perlite.[5] The mixture must be sterile in order to avoid introducing potentially harmful microbes.[5]

Open terraria

Open terraria are better suited to plants that prefer less humidity and soil moisture, such as temperate plants. Not all plants require or are suited to the moist environment of closed terraria. For plants adapted to dry climates, open, unsealed terrariums are used to keep the air in the terrarium free from excess moisture.[6] Open terraria also work well for plants that require more direct sunlight, as closed terraria can trap too much heat potentially killing any plants inside.

Note that succulents, despite being a popular option, are a poor choice for terraria - open or closed. The intrinsic lack of drainage in a terrarium will inflict root rot or require under watering.

See also bottle garden.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terrariums. |

- Honigsbaum, Mark (2001). The Fever Trail: The Hunt for the Cure for Malaria. MacMillan. ISBN 9780333901854.

- "The History of Terrariums". StormTheCastle.com. Kalif Publishing and StormtheCastle.com. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "Dr. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward". Plantexplorers.com. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Maylack, Jen (12 November 2017). "How a Glass Terrarium Changed the World". The Atlantic. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Trinklein, David H. "Terrariums". University of Missouri Extension. University of Missouri. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Mo, Denny. "Laws of The Terrarium". Terrarium-Life in A Glass. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2014.