Te Kooti's War

Te Kooti's War was among the last of the New Zealand wars, the series of 19th century conflicts between the Māori and the colonising European settlers. It was fought in the East Coast region and across the heavily forested central North Island and Bay of Plenty between New Zealand government military forces and followers of spiritual leader Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki.

| Te Kooti's War | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of New Zealand Wars | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

Ngāti Porou Māori Ngāti Kahungunu Māori |

Māori Ringatū adherents Māori Pai Mārire adherents Ngāi Tūhoe Māori Ngati Hineuru Māori Rongowhakaata Māori | ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

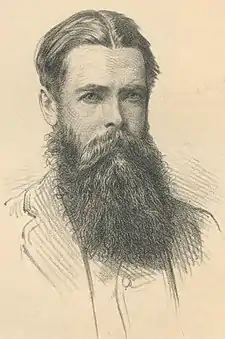

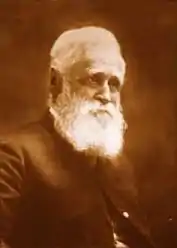

Colonel George Whitmore Major Thomas McDonnell Major Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui Major Ropata Wahawaha Major William Mair Hotene Porourangi Captain Gilbert Mair Henare Tomoana Renata Kawepo |

Te Kooti Te Rangitahau | ||||

The conflict was sparked by Te Kooti's return to New Zealand after two years of internment on the Chatham Islands, from where he had escaped with almost 200 Māori prisoners of war and their families. Te Kooti, who had been held without trial on the island for two years, told the government he and his followers wished to be left in peace and would fight only if pursued and attacked. But two weeks after their return to New Zealand, members of Te Kooti's party found themselves being pursued by a force of militia, government troops and Māori volunteers. Te Kooti's force routed them in an ambush, seizing arms, ammunition, food and horses. The engagement was the first in what became a four-year guerrilla war, involving more than 30 expeditions[1] by colonial and Māori troops against Te Kooti's dwindling number of warriors.

Although initially fighting defensively against pursuing government forces, Te Kooti went on the offensive from November 1868, starting with the Poverty Bay massacre, a well-organised lightning strike against selected European settlers and Māori opponents in the Matawhero district, in which 51 men, women and children were slaughtered and their homes set alight. The attack prompted another vigorous pursuit by government forces, which included a siege at Ngatapa pā that came to a bloody end: although Te Kooti escaped the siege, Māori forces loyal to the government caught and executed more than 130 of his supporters, as well as prisoners he had earlier seized.

Dissatisfied with the Māori King Movement's reluctance to continue its fight against European invasion and confiscation, Te Kooti offered Māori an Old Testament vision of salvation from oppression and a return to a promised land. Wounded three times in battle, he gained a reputation for being immune to death, uttered prophecies that had the appearance of being fulfilled, and developed an image of a mighty warrior riding a white horse, reflecting themes of Christian apocalypticism.[2]

In early 1870 Te Kooti gained refuge with Tūhoe tribes, which consequently suffered a series of damaging raids in which crops and villages were destroyed, as other Māori iwi were lured by the promise of a £5000 reward for Te Kooti's capture. Te Kooti was finally granted sanctuary by the Māori king in 1872 and moved to the King Country, where he continued to develop rituals, texts and prayers of his Ringatū faith. He was formally pardoned by the government in February 1883 and died in 1893.

A 2013 Waitangi Tribunal report said the action of Crown forces on the East Coast from 1865 to 1869, the East Coast Wars and the start of Te Kooti's War, resulted in the deaths of proportionately more Māori than in any other district during the New Zealand wars. It condemned the "illegal imprisonment" on the Chatham Islands of a quarter of the East Coast region's adult male population and said the loss in war of an estimated 43 per cent of the male population, many through acts of "lawless brutality", was a stain on New Zealand's history and character.[3]

Background to war

Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki was born about 1832 into the Ngati Maru sub-tribe of the Māori people in Poverty Bay on the south shore of East Cape. By the age of 20 he had become known as one of a group of "bother boys" or "social bandits" who led protests over land rights in the Makaraka district near present-day Gisborne, seizing horses and cattle that were being grazed without agreement on Māori land and also plundering settlers' homes, often taking alcohol. The protests were part of a movement to recover occupied land and set up a "coalition" against the government.[4]

Despite his involvement in land politics, Te Kooti stayed clear of the Pai Mārire (Hauhau) religion when it spread to the East Coast in early 1865.[5] He fought with kūpapa ("loyal") Māori and government troops against Pai Mārire men, women and children in the week-long siege of Waerenga-a-Hika in October 1865. Te Kooi claimed to have killed two Pai Mārire fighters in the battle, but was accused of being a spy and was arrested after the siege ended. He was released after an investigation, but five months later, on 3 March 1866, he was seized again—for reasons now unclear, but probably after accusations by prominent Māori and settlers he had antagonised—and shipped with several hundred Pai Mārire prisoners and their families to the Chatham Islands for internment without trial.[5] His repeated pleas to be told of what offence he had been accused of, and to be put on trial, were ignored.[6]

Prisoners were kept in poor conditions with minimal health care and forced to build roads and barracks and plough cultivations without the aid of animals. In April 1867, a year after their arrival, prisoners were told they would not be repatriated until East Coast land confiscations had been determined. By 1868 the mood of the exiles darkened as they realised there were no plans to return them to New Zealand.[7] On 4 July 1868 Te Kooti led a carefully planned and executed breakout from their internment, overpowering guards, seizing arms and ammunition and commandeering a schooner, the Rifleman, which was moored at the settlement of Waitangi. A total of 298 people—163 men, 64 women and 71 children—sailed out of the Chatham Islands, arriving at a secluded cove at Whareongaonga, south of Turanga (modern-day Gisborne), on 9 July.[8]

During his time of exile Te Kooti claimed he experienced a series of spiritual revelations that formed the basis of what became known as the Ringatū ("Raised hand") faith,[9] which was strongly influenced by Old Testament prophecies of divine direction and deliverance from enemies. The apparently unerring fulfillment of Te Kooti's predictions won him the unwavering support of other whakarau (prisoners), and in a letter given to the crew of the Rifleman after arrival in New Zealand, he wrote that Jehovah had intervened to deliver his people from their captivity. The letter also asked that they be left in peace and not be pursued as they made their way to the interior of the North Island.[8]

While in the Chathams Te Kooti also learned of the sale of disputed Poverty Bay land in which he held an interest. The transactions involved many of those, both Māori and European settler, whom he later killed in his Poverty Bay campaigns.[10]

First engagements

On the morning of 12 July 1868, three emissaries arrived at Whareongaonga, passing on a demand from Major Reginald Biggs, Turanga's resident magistrate and militia commanding officer, that they were to surrender their arms and await the government's decision on their future. Te Kooti rejected the demand, declaring he would fight only if he was pursued and attacked.[11] As Biggs scrambled to assemble a force with which to confront Te Kooti at Whareongaonga—his militia volunteers, the Mounted Rifles under Captain Charles Westrup, as well as other men from Wairoa and Napier—the whakarau, whose fighting force then numbered about 60, set off on 14 July, bound for the King Country, where Te Kooti hoped to challenge the mana of Māori King Tāwhiao, who similarly claimed to be the mouthpiece of God. Te Kooti intended to eventually settle in the village of Tauranga, on the eastern shore of Lake Taupo.[11] Biggs, arriving at Whareongaonga and discovering he had missed Te Kooti, marched his 70-strong force to Paparatu, about 40 km away, across a more direct route through open country, intending to cut off his quarry as they crossed the Arai Stream. Biggs left Westrup in command at Paparatu and returned to Turanga to organise a resupply. On the morning of 20 July Te Kooti lured Westrup's force into an ambush, killing two Europeans and forcing a retreat. He seized food, arms and ammunition and 80 horses.[11][12][13]

Further victories were achieved at Te Koneke on 24 July and then at Ruakitori Gorge, near their new base at the ancient pā at Puketapu, on 8 August, when Te Kooti's force defeated a column led by the commandant of the Armed Constabulary, Colonel George Whitmore, whom Te Kooti now dubbed "Witi koaha", or "witless". The succession of victories attracted more recruits to Te Kooti's party, including Ngati Kohatu chief Korohina Te Rakiroa, who brought with him up to 20 men with government-issued rifles.[12][13][14] A crucial bond was also struck between Te Kooti and a high-ranking chief of inland Wairoa, Te Waru Tamatea, a Pai Mārire convert whose son had been taken prisoner in October 1865 during the East Cape War and executed at Biggs' command. Te Waru and fellow chief Nama, survivors of the Waerenga-a-Hika siege, had earlier fought for autonomy for themselves and their people but were now bitterly opposed to the land confiscations that had followed the East Cape War; the failure of the Crown to return their land despite a confiscation settlement a year earlier deepened their resentment. Te Kooti's force was now even stronger, and he was also now committed to aiding Te Waru to achieve utu over his son's death.[14]

In Taranaki, meanwhile, government forces were suffering humiliating defeats at the hands of bush warrior and Pai Mārire prophet Riwha Titokowaru. In the wake of their devastating loss at Te Ngutu o Te Manu in early September 1868, Whitmore was sent to Taranaki to assume command, and took the entire east coast Armed Constabulary force with him. The government, eager to free further resources for use against Titokowaru, seized the moment to offer Te Kooti a peace agreement. In mid-October Defence Minister Theodore Haultain directed that a message be sent to Te Kooti at Puketapu stating that if the prisoners surrendered themselves and their arms, no further proceedings would be taken against them and land would be found for them to live on. Historian James Belich commented that the offer was almost certainly genuine and, if accepted, "could easily have made Te Kooti's first campaign his last". Catholic missionary Father Euloge Reignier was chosen to act as the emissary and negotiator, but was prevented from reaching Te Kooti and instead passed the message on via Pai Mārire warriors. If Te Kooti did receive the offer, he rejected it, suspicious of the government's intentions and aware they planned to storm Puketapu.[12][15]

Unable to move forward or backward without the threat of attack, Te Kooti launched an intensive campaign for Māori support, seeking Tāwhiao's assent to enter the King Country and also asking Tuhoe chiefs permission to enter their land. While Tuhoe deferred their decision, Tāwhiao sent an outright rejection, warning they would be repelled if they encroached on his territory. Three months after arriving at Puketapu, and by now with a fighting force of about 250—many of them drawn from tribes who shared his outrage at spreading land confiscations—Te Kooti announced they would return to Turanga. He told his followers: "They did not listen. Now we must turn and strike them. Now Turanga shall be given us to dwell in."[15]

Poverty Bay massacre, Ngatapa siege

On the night of 9 November 1868 Te Kooti led a war party towards Turanga, a district that was home to about 150 European settlers and 500 Māori, in preparation for what became known as the Poverty Bay Massacre or Matawhero Massacre.[16] He emerged about midnight from the Patutahi valley, about 15 km northwest of the European township, accompanied by a 100-man kokiri, or attack party, 60 of whom were mounted. The kokiri was split into two main contingents, with almost all their targets in the farming district of Matawhero, on Turanga's outskirts, where land formerly owned by Te Kooti had been sold and settled during his internment. The first attack force, led by Nama, struck first at the family of Captain James Wilson, killing Wilson, a servant and three of his four children and fatally wounding his wife. The second, and larger, kokiri led by Te Kooti surrounded Biggs' home where he, his wife, their baby and servants were fatally shot, clubbed and bayoneted. The attackers moved on to other homes, slaughtering the families of other settlers who had fought with the militia forces and setting fire to their houses. Many of the killings were followed by the singing of Psalm 63, which concluded: "They who seek my life will be destroyed ... they will be given over to the sword and become food for jackals."[17] A total of 29 Europeans and part-Māori were killed, as well as 22 Māori, specifically selected by Te Kooti for slaughter for what he perceived as double-dealing or disloyalty over his land during his exile.[18]

By the following morning Te Kooti was in control of all land between the Waipaoa River and Makaraka. He remained in the district until 13 November, continuing to take Māori prisoners, before marching his followers and prisoners inland to Oweta pā, where he took more prisoners and executed four chiefs. When he left the pā on 19 November, satisfied he had "reclaimed" Turanga, he was leading 600 people, half of them prisoners, including women and children.[18]

The whakerau arrived at Te Karetu, a small pā at the junction of the Wharekopae and Makaretu rivers, on 22 November.[19] By then they were already being pursued by a force of 340 Ngāti Kahungunu raised from Napier and Mahia as well as a contingent from Ngāi Tahupo at Muriwai in Poverty Bay. The pursuit force reached Te Karetu on 23 November, but despite having more than double the number of Te Kooti's men—only 150 of whom had rifles—they were kept at bay until the arrival on 2 December of 180 Ngāti Porou fighters led by Ropata Wahawaha. Whitmore, having put on hold his pursuit of Titokowaru on the west coast, arrived in Poverty Bay with 220 Armed Constabulary divisions two days later and joined the campaign.[20] About 40 of Te Kooti's rearguard were killed in the subsequent assault, while Nama was captured, tied up and then dragged repeatedly through fire until he died.[19] It was a hollow victory for Ropata, however, with the pā found to be almost empty. Te Kooti had moved most of his fighters, along with women, children, food and livestock, to the ancient hilltop fortress of Ngatapa, about 5 km further inland.

Ngatapa was a formidable pā, standing 700 metres above sea level and surrounded by cliffs on three sides and dense bush on the side facing any opposing force. Te Kooti had hastily begun strengthening its defences with trenches, earth banks and palisades, as well as covered walkways connecting the trenches. The interior of the pā was a maze of rifle pits. Ropata moved his force towards Ngatapa on 3 December, but a day later suffered a blow as Ngāti Kahungunu members of his contingent quit the battle and withdrew after a dispute with Ngāti Porou fighters, who wished to kill some of the prisoners. The next day, with as few as 150 men, he gained some ground in a rush on the pā, but was forced to abandon the assault a day later and return to Turanga, short of gunpowder and men. Yet Te Kooti's losses were also mounting: since 23 November he had lost at least 57 men and 60 of his rifles had been captured and many of his Turanga prisoners had also escaped.[21][22]

Desperate for arms and ammunition, Te Kooti led a second lightning raid on Turanga with about 50 men on 12 December, killing four locals but failing to secure the supplies they needed. The raid galvanised Whitmore to renew his campaign against Te Kooti, which he had decided just days earlier to abandon after false reports that Te Kooti had quit Ngatapa and retired inland. His troops, who were already being prepared for a return to Wanganui, were turned around and planning began for a second, better equipped assault on Ngatapa.[20][21] The 600-man force—250 Europeans in the Armed Constabulary, 60 Arawa led by European officers and over 300 Ngāti Porou led by Ropata and Hotene Porourangi—massed at Ngatapa on 31 December and launched the attack the following day, quickly besieging the 300 occupants of the pā and cutting off their water supply from a hidden spring. Whitmore placed his men on all sides of Ngatapa except one, a high rocky precipice on the north side which was considered far too steep for use as an escape route. Heavy rain fell as the siege continued and when it began to clear on the fourth day, Whitmore commenced a mortar attack, briefly pounding the pā before halting its use when shrapnel ricocheted off the hill and also went right over it, landing among Hotene's men on the far side. Te Kooti abandoned his outer defences on 5 January after Arawa and Ngāti Porou fighters climbed the rock face and kept up heavy fire, while others in Whitmore's force began an offensive sap towards the remaining rampart.

Alerted by a woman's cry early on 6 January that there were no men left in the pā, the attackers entered to find just 20 women and children, most of them prisoners, inside. During the previous night at least 190 occupants of Ngatapa had descended from the unguarded steep rock outcrop, lowering themselves more than 20 metres down the almost perpendicular face on vines woven to form a rope or ladder. Ngāti Porou set off in immediate pursuit and flushed out 130 male prisoners from the bush and gorges below. The prisoners were marched up the hill to the pā's outer parapet, stripped naked, then shot dead. Some were then beheaded. Just 80 prisoners, including 50 women and 16 children—most of them emaciated and skeletal—were spared execution, with most taken by Ngāti Porou as their own prisoners. About 14 male prisoners were kept to be put on trial.[21]

While kupapa losses were between 40 and 50 killed and wounded,[22] the defeat for Te Kooti was far more critical, with 136 men, most of his fighting support, killed and 60 of his male prisoners escaping.[21]

Retreat to the wilderness

Te Kooti and his remaining followers retreated into the Urewera mountains, where he forged alliances with Tuhoe leaders from the Upper Wairoa and Waikeremoana districts who had similarly been dispossessed of their land by the government's punitive confiscation policies, declaring: "I take you as my people, and I will be your God." Historian Judith Binney claims Te Kooti offered the Tuhoe chiefs a new form of Māori unity:

"This new order rejected the Maori kingship as a failed experiment, already being eroded by whispering words from the government. This judgment was harsh, but it recognised that the King would no longer fight. Te Kooti instead sought to direct people through his vision, based in the covenant promises to the Chosen of God. He also warned them of the consequences of faltering in the pursuit of this vision: their own destruction. It was a fearsome vision, to which many of the Tuhoe were drawn."[23]

Yet other Tuhoe chiefs remained wary of an alliance, anticipating the trouble he would bring to the region and its people. It was not long in coming.

On 2 March 1869 he launched the first of a new wave of east coast guerrilla raids aimed at gaining arms and ammunition and persuading other Māori groups to join his cause and boost his force of warriors. Te Kooti's men raided both the Whakarae pā at Ohiwa, near Whakatane, and nearby Hokianga Island, taking all occupants without resistance, before killing a surveyor, Robert Pitcairn. A week later, on 9 March, he besieged a Ngāti Pukeko pā, Rauporoa, on the west bank of the Whakatane River, taking the pa but losing key Taupo ally Wirihana Te Koekoe, who had earlier assured him of sanctuary at the lake. He took more prisoners at Paharakeke, on the Rangitaiki River, then gained more supporters as his forces rode further inland, pursued unsuccessfully by a government force of 450 led by Major William Mair.[24] His new series of raids prompted the evacuation to Auckland of most European women and children in the Bay of Plenty.[25]

Early on 10 April 1869, five months to the day after his infamous Poverty Bay raid, he launched another devastating surprise strike, this time on Mohaka, south of Wairoa. Te Kooti's aim was twofold: to seize supplies from the well-equipped kupapa tribes and to exact revenge on Ngāti Kahungunu for their war against Te Kooti in 1868. Divided into two kohiri with Tuhoe and Ngāti Hineuru fighters prominent among his 150-strong force, they swept through the village of Te Arakinihi at Mohaka, killing 31 men, women and children and seven nearby settlers, some of whom had served in the militia, before moving to their primary targets, Te Huki pā and the bigger Hiruharama pā on the coast. Te Huki was besieged overnight before being taken the next morning amid a slaughter of its 26 occupants, most of them women and children. The raid netted Te Kooti enough ammunition to assault Hiruharama, but an attempted siege of the bigger pā collapsed when outside reinforcements arrived to help the defenders and the cache of ammunition within the pā exploded, rendering pointless any further battle. Once again Te Kooti retreated to the Tuhoe heartland.[23]

News of the March raids near Whakatane had already reached Whitmore in Taranaki, who by then was abandoning his pursuit of Titokowaru. Whitmore and Native Affairs Minister James Richmond resolved to shift the main colonial force to the east coast and by 20 April Whitmore and 600 Armed Constabulary were in Opotoki, preparing for the formidable task of invading the Urewera mountains with the twin aims of capturing Te Kooti[24] and destroying all Tuhoe settlements, and therefore their ability to shelter him.[23] Whitmore organised a three-pronged invasion, all converging on Ruatahuna, the likely centre of resistance: the first from Wairoa in the south and crossing Lake Waikeremoana, led by Lieutenant-Colonel J. L. Herrick, a second under Lieutenant-Colonel St John that would leave Opotiki in the Bay of Plenty and invade from the north, pushing up the Whakatane River; and a third led by Whitmore himself, that would move up the Rangitaki River from Whakatane, building a chain of forts to Tauaroa, and entering the Urewera from the west. The force totaled about 1300 troops: 620 constabulary, 95 militia and 500 kupapa, evenly divided between the three columns—more than the entire population of the Urewera.[24][26] Whitmore's column took the first blood about noon on 6 May, killing six men defending Te Harema pā and taking 50 prisoners, most of them women and children, who were given to the Arawa contingent. The pā was looted and later burned.

Whitmore continued on to Ruatahuna, rendezvousing with St John on 7 May 1869. The two commanders spent the next few days systematically destroying all settlements, crops and livestock in Ruatahuna in an attempt to drive the Tuhoe people to starvation. The mission faltered on 12 May when, after a brief clash with Te Kooti's advance guard, the Arawa fighters refused to advance beyond Ruatahuna[26] and dozens of government forces, including Whitmore, succumbed to dysentery. Whitmore's men withdrew from the Ureweras within a week.[24] Herrick's expedition, however, pushed on, finally reaching Onepoto, at the Lake Waikaremoana's south, on 24 May, and labored at building a fleet of boats to cross to the north side of the lake to where Te Kooti was sheltering—a venture that continued until 8 July when Herrick scuttled his boats and returned south.[27] But Whitmore's scorched earth strategy had achieved its aim: in late May Tuhoe chiefs turned on Te Kooti and demanded he leave their territory.

Te Kooti turned again towards Taupo, travelling in a convoy of about 200 people, 50 of them mounted. He seized prisoners and livestock at the settlement of Heruiwi, before launching a daring raid on an encampment of volunteer cavalry at Opepe, 20 km west of Lake Taupo, on 7 June, killing nine soldiers and capturing all their arms and horses.[23][24][28] He destroyed the pā of two hapu who had earlier refused to give him refuge or assistance, then arrived on 10 June at Tauranga, at the southern end of Lake Taupo, occupying the settlement for more than a week before moving to Moerangi, southwest of the lake, taking more prisoners as he travelled.

Early in July Te Kooti and his followers and prisoners, a group of possibly more than 800, set off for Tokangamutu, the temporary residence of Māori King Tāwhiao near Te Kuiti, where he hoped to either force Tāwhiao into an alliance or topple him.

Challenge to King Tāwhiao

A meeting between Te Kooti and Tāwhiao, had it taken place, would have been a confrontation of two prophets and leaders, each of whom had taken diametrically opposed positions on further war with the government. While Te Kooti viewed warfare as the means by which his vision of the return of their land would be fulfilled, Tawhiao had renounced armed conflict and declared 1867-68 as the "year of the lamb" and "year of peace"; in April 1869 he had issued another proclamation that "the slaying of man by man is to cease".[29] Though there were radical elements in the Kingitanga movement who favoured a resumption of war, including Rewi Maniapoto and possibly Tāwhiao himself, moderates continued to warn the King that they had little chance of success and risked annihilation by becoming involved in Te Kooti's actions.[30] Te Kooti had been angered by Tāwhiao's refusal the previous November to send reinforcements during their campaigns near Gisborne and had then threatened that if he remained aloof he would be cursed by Jehovah, who would command Te Kooti to march to Te Kuiti and put the king and his people to the sword.[29]

Tamati Ngapora, a senior adviser to the King, had invited Te Kooti to Te Kuiti, but on the proviso that he came in peace. Te Kooti's response was one of defiance, warning that he was coming to "assume himself the authority which he coming directly from God was entitled to".[31] His chief aim for the visit was simple: to rouse Tāwhiao's support for renewed war against the government and wrest back the confiscated land. Accompanied by Horonuku and about 200 Tuwharetoa, he arrived at Te Kuiti on 10 July 1869, immediately declaring that he was the host (tangata whenua) and that the Waikato were his visitors. At an assembly attended by 200 Waikato Māori, Te Kooti urged them to hold the land and keep up the fighting. But though Te Kooti remained there for 15 days, with the village in a heightened state of tension as he continued to challenge the mana of the king, Tāwhiao refused to emerge from his home to meet him. Te Kooti was finally offered every support short of actual hostilities—as well as a place of sanctuary inland on the Mokau River under the protection of Ngāti Maniapoto.[23][30][32]

News of Te Kooti's presence in Te Kuiti, and the prospect of the two Māori leaders forming an alliance, alarmed the government. Premier William Fox said the development heightened "the probability of a combined attack on the settled districts in the neighbourhood of Auckland" and both Houses of Parliament accepted government motions asking Major-General Sir Trevor Chute, commander of the British forces in New Zealand, to cancel orders for a planned withdrawal of the 18th Regiment, the sole remaining British regiment in New Zealand.[33] Yet Binney has speculated that history could well have turned had Tāwhiao decided to join Te Kooti's campaign. In official correspondence between Auckland and London in 1869, Governor George Bowen advocated granting "a separate principality" for Tāwhiao as a means of attaining peace, while the British government similarly urged the colonial government to "cede the lands conquered by the Queen's troops" and surrender "the Queen's sovereignty" in those areas, while recognising "absolute dominion" by the King within his borders. Premier Fox, who was desperately trying to cut military expenditure, strongly opposed proposals for Māori self-government under the Māori king, as urged by Bowen and former Chief Justice Sir William Martin, but the formation of a more robust pan-Māori alliance could have become a tipping point to create a system of separate Māori rule in their territory.[33][34][35]

Taupo campaign and defeat at Te Pōrere

Accompanied by Rewi Maniapoto, Te Kooti and his followers left Te Kuiti and returned to Taupo, settling briefly at its southern end on 18 August before launching a Taupo campaign that took him to the brink of defeat. News of his return prompted the formation near Taupo of a 700-strong government force, with all but about 100 of them kupapa: Ngāti Kahungunu (230 men), Wanganui (160), Ngāti Tuwharetoa (130) and Arawa (50).[30] On 10 September 1869 Te Kooti's force of about 280 mounted a pre-emptive strike against a 120-man mounted Ngāti Kahungunu contingent, led by Henare Tomoana, which was camped at Tauranga-Taupo. But although Te Kooti took their horses and much of their equipment, he was forced to retreat under heavy fire. Three of his force were killed and several wounded. They then retreated to Moerangi, inside the relative security of the Rohe Potae or King's territory—an area the government considered too dangerous to attack, for fear of reviving Kingitanga aggression. At this point Rewi separated from Te Kooti and returned to the Waikato, unimpressed by Te Kooti's performance in battle and angered by the slaughter at Rotoaira on 7 September of four Māori scouts with Waikato connections. Any chance of a compact between Te Kooti and the Kingitanga had now vanished.[36]

Less than two weeks later, on the morning of 25 September, Te Kooti returned to Tokaanu with 250 to 300 fighters for what eventuated as a disastrous attack. After striking from the densely forested hills of Te Ponanga saddle south of Tokaanu, they were driven back by a joint force of Henare Tomoana's Ngāti Kahungunu and Hohepa Tamamutu's Tuwharetoa. Te Kooti dug in at nearby Te Ponanga, but lost seven in battle, including Wi Piro, a close relative who had been prominent in all the Ringatu raids. The heads of his wounded warriors were severed by members of the government force.[36][37]

But the most ignominious defeat was to come. Amid sleet, snow and driving winds, Te Kooti began preparing an earthwork redoubt at Te Pōrere near Papakai village, about 9 km west of Lake Rotoaira on the lower northwest slopes of Mount Tongariro. The redoubt was built in the form of a European fortification, about 20 metres square, with 3 metre-high walls built of sod and pumice, bound with layers of fern. The structure was designed for a fixed battle, a style of conflict that Te Kooti had previously avoided. Government forces, under the command of Major Thomas McDonnell, arrived at Papakai in the first week of October and launched an assault with 540 men on the morning of 4 October in heavy rain. Ngāti Kahungunu and Arawa forces led by Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui—better known to Pākehā as Major Kemp—quickly took the outer trenches, then stormed the redoubt, discovering a fatal design flaw hindered the ability of those inside to effectively maintain fire on an attack force: the loopholes in the parapets had been built without allowing warriors to depress their gun barrels and aim at targets below. As the fight raged, Captain John St George—who had fought since 1865 against Pai Marire and Ringatu forces—was killed while leading his force on a charge, and a bullet struck Te Kooti in the hand and severed a finger. It was his third injury in battle, after sustaining an ankle injury at Puketapu and a shoulder wound at Ngatapa. In what turned out to be the last major battle of the New Zealand Wars, between 37 and 52 of Te Kooti's force were killed—a sixth of his fighting force—and more than 20 women and children taken prisoner at Te Porere. The government loss was four killed and four wounded. Within days Horonuku, who had been sheltering in the bush after escaping, surrendered.[37][38][39] Belich noted: "Te Porere was Te Kooti's last stand in a prepared position, and his last attempt at anything other than raid, ambush and the evasion of pursuit."[30]

Flight

Te Kooti and his followers—men, women and children—separated and scattered after the Te Pōrere defeat, many of them finding shelter in bushland in the upper Whanganui River. On 9 November Defence Minister Donald McLean met Rewi Maniapoto, Tamati Ngapora and other Kingitanga chiefs, demanding that they surrender Te Kooti. Rewi refused, declaring that he would provide a sanctuary for Te Kooti within the Rohe Potae as long as he remained peaceful, but would hand him over if he caused trouble. But at a hui of upper Whanganui chiefs 10 days later, influential chief Topia Turoa declared that in revenge for earlier killings by Te Kooti of several kinsmen and a priest in the Taupo district, he would start his own search for the Ringatu leader from the east, while Te Keepa (Major Kemp) would comb the forest from Taupo in the west. Topia's campaign against Te Kooti and his 30 immediate followers gained the approval of Tāwhiao, who now reversed his oath to sheath the sword, and the Whanganui chief sent out almost 400 scouts in search of his quarry.[40]

At the end of December 1869 to the first week of January 1870 both Te Keepa and Topia and their combined force of 600 came close to capturing Te Kooti—again with a fighting force of about 90 and 200 women and children—in the upper Whanganui River near Taumarunui but were thwarted by floodwaters.[40] On 16 January he reappeared at Tapapa, in the Waikato district, and arranged a meeting with Matamata settler and runholder Josiah Firth a day later. He sought Firth's help in achieving a truce with the government. He told him he would not surrender to the authorities, but said: "I am weary of fighting, and desire to live quietly at Tapapa. If I am let alone I will never fight more, and will not hurt man, woman or child."

Firth passed the message to Daniel Pollen, the government's agent for Auckland province, who promised that no military movement would occur while the two negotiated. But when Pollen returned to Auckland to pass on Te Kooti's proposal, he was rebuked by Fox, who ordered the agent to cease interfering in the military campaign. Fox wrote to Pollen that Te Kooti was "a midnight murderer of defenceless women and helpless children ... a man of atrocious cruelty and outrage" who was "repudiated and abhorred by the bulk of his people".[40]

Fox continued preparations for a large-scale confrontation and within days substantial forces were closing in on Tapapa: McDonnell and 250 men approached from Tokaanu up the eastern side of Lake Taupo; Te Keepa, Topia and 370 Wanganuis moved up the west side; Lieutenant-Colonel William Moule and 135 constabulary and militia came south from Cambridge and Lieutenant-Colonel James Fraser with 90 constabulary and 150 Arawa moved to block Te Kooti's retreat to the Urewera. Another 210 Arawa were also on the march to join McDonnell. Against those 1200 men, Te Kooti may have had as few as 100 men.[41] Te Kooti slipped out of Tapapa as the force arrived, and on 24 January the government forces seized and burned the deserted village. Early the next morning Te Kooti launched a surprise raid on the military camp, with each side losing about four men before te Kooti was driven off. Although Te Keepa managed to recapture about 100 of the horses Te Kooti had been using, the government party lost the trail of the skilled guerrilla fighter.

On 3 February 1870 there was one more skirmish as Te Kooti and 40 warriors, camping in dense bush at Paengaora as they travelled north towards present-day Te Puke, ambushed a 236-strong force led by Fraser, killing three or four, before vanishing again as they headed south. Four days later they appeared beside Lake Rotorua, where Te Kooti sought a truce directly with Te Mamaku and local Arawa, and asked local Māori for permission for his party—240 men and 100 women—to cross their land towards Ruatahuna in the Ureweras. Gilbert Mair, who arrived soon after with a contingent of Arawa fighters, was angered by the request, which was being considered by local chiefs, and ordered his men to pursue Te Kooti. Following just 3 km behind, Mair's force began a 12 km chase that turned into a series of running battles, engaging the rearguard of Te Kooti's forces before being halted by an ambush. Two of Te Kooti's two key fighters, Peka Makarini and Timoti Hakopa died in that engagement and as night fell, Te Kooti and about 200 with him plunged into the bush, moving rapidly southeast through the night beyond Lake Rotokakahi before emerging in the Urewera, and under the protection of the Tuhoe.[42] In 1886 Mair was awarded the New Zealand Cross for his bravery in the events of 7 February 1870.[43]

Pursuit

.jpg.webp)

Within days McDonnell was relieved of his command and McLean, as Native Minister, announced that from 11 February 1870 Māori would control all the expeditions, with no European involvement. There would be no daily pay for soldiers, instead they would compete for £5000 reward offered for Te Kooti's capture.[44] The pursuit was instead led by both Te Keepa with his Whanganui warriors, and Ropata and his Ngati Porou, with two companies of Arawa Armed Constabulary, picked from the tribes at Rotorua, Rotoiti, Tarawera, Matata and Maketu, also joining the fight.[45]

On February 28 Te Kooti struck south of Whakatane, destroying a mill of an enemy chief, then a week later raided Opape, east of Opotiki, seizing arms and gunpowder and capturing more than 170 men, women and children, intending to hold them ransom to gain more male fighters for his force. He retreated to the Maraetahi region, about 10 km south of Opotiki, where he had established earlier a small village, complete with acres of maize and other crops. Te Kooti remained undisturbed there for a month until the arrival on March 25 of forces led by both Ropata—picking their way up the boulder-strewn Waioeka River from the south—and Te Keepa, who was marching down the river from the north. An hour-long firefight erupted before the village and nearby Raipawa pā were taken. About 300 occupants were taken prisoner, all but 87 of them being Whakatohea prisoners, and about 19 taken captive were executed in the riverbed by tomahawk or gun. Te Kooti managed to flee with about 20 men.[44]

This was the end of Te Keepa's war. He and his men had pursued Te Kooti right across the North Island for seven months. They were operating far from their own territory, fighting on behalf of the Government against an enemy who had never threatened his own people. They felt they had done enough. The New Zealand Wars were over and it was time to go home.

But the pursuit of Te Kooti was not over, for it was to continue for another two years. In July 1871 Ropata Wahawaha, Tom Porter and Ngati Porou were joined by Captain Gilbert Mair and Captain George Preece leading a taua (war party) of Arawa. Together they ranged through the Urewera Mountains, subjugating the Tuhoe and forcing them to hand over any fugitives they were sheltering.[46] One welcome catch who fell into Ropata's hands was Kereopa Te Rau, accused of Volkner's murder – he was worth 1000 pounds to his captors.

On 22 September 1871, Captains Mair and Preece started from Fort Galatea on another Urewera expedition. The Arawa forces unexpectedly came upon Te Kooti's camp, which was taken after a brief skirmish. Wi Heretaunga was captured. He was believed to a participant in the murders of Captain James Wilson and his family at Matawhero in November 1868.[47] He was also accused of being involved in the Mohaka massacre in April 1869. It was decided, that he should be shot, and this summary execution was carried out.[46] When in camp Te Kooti usually slept some distance away from his followers. This habit had saved him at Maraetahi and it did so again. He was almost killed but another man intercepted the bullet. He fired one shot and fled, naked, into the bush, and the hunt continued.[46]

Early in February 1872, Preece received good information about the whereabouts of Te Kooti, at the junction of the Waiau and Mangaone Streams. On 13 February they found a camp that had been occupied only a few days previously. The next day they found a camp with a fire still burning and then spotted a group of people climbing the cliff on the opposite side of the flooded stream. One of them was Te Kooti. Shots were exchanged and the chase was on. Later the same day Nikora te Tuhi spotted Te Kooti in the distance and fired two shots at him. They both missed but they were the last shots fired in the New Zealand Wars.

Te Kooti continued to elude the pursuers. On 15 May 1872 he crossed the Waikato River and once again entered the territory of the Māori King, Tawhiao. This time he approached the King as supplicant and was granted asylum.

Pardon and later years

In 1883, the Government formally pardoned Te Kooti[48] as part of a deal with Tawhiao to put the Main Trunk Line through the King Country.[49] Almost immediately Te Kooti showed his gratitude by rescuing a surveyor, Wilson Hursthouse, who had been taken prisoner, stripped and chained up by Te Whiti o Rongomai's men from Parihaka.[50] However Te Kooti remained unrepentant and belligerent. He went about armed with a revolver and threatened to take his gang back to Poverty Bay. He travelled extensively holding meetings to spread the ringatu message. He was often accompanied by large groups of supporters to places such as Whakatane and Opotiki. An observer noted 1,000 people gathered to hear him and the resident magistrate commented that for once Te Kooti was sober. Te Kooti was still far from popular with all Maori and was accused by chiefs of practicing maketu (black magic) to kill senior chiefs who he had previously opposed him. Chiefs were concerned that groups such as Ngati Awa and Ngati Pukeko would hand over the land to Te Kooti without any authority. The chiefs wrote to parliament to complain that Te Kooti was claiming mana over their land and instructing that the land should not be bought before the Native land Court. The chiefs were also concerned that the supplies of the communities were being drained by massive hui leading to the people being ill-prepared to face winter. Chiefs complained that Te Kooti was forcing his adherents to raise money for him by selling family crops and animals. School teachers and native officers sent report to the government that this was resulting in children being malnourished.[51] Bush, the local magistrate, became concerned about "Te Kooti-ism" -Te Kooti was telling his followers that confiscated land would be returned by driving the Pakeha from the country.[52] This alarmed the government and the people of Poverty Bay. In February a telegram signed by 20 chiefs went to parliament saying they would rise up if Te Kooti did not turn back.[53] The government was keen to keep the peace. The Minister of Defence was concerned that Te Kooti had been directly threatened by his old adversaries Ropata and the Ngati Porou. The Prime Minister arranged a meeting in Auckland between himself, Te Kooti and the Native Minister where he was offered government land if he stayed away from Gisborne. Although cordial, Te Kooti told the officials that he determined to return. As a token of his peaceful intentions he surrendered a small revolver that he normally carried.[54] The government shipped troops and artillery to Gisborne to form a military force of 377 under Major Porter in early 1889. Rumours of threats continued until the force went to Waioeka Pa and found Te Kooti drunk with 4 of his wives and some 400 supporters, who were arrested.[55] He was bound over to keep the peace but as he could not afford the fine or bond he was taken to Mt Eden jail in Auckland where he was persuaded by the Ladies Temperance Movement to take the pledge against drinking alcohol and imprisoned for a short time before being released. Te Kooti wrote a letter of apology to the government explaining that his recent conduct had been caused by drink.[56] Eventually in 1891 the government gave him an area of land at Wainui, where a marae for the Ringatu church was later established. Te Kooti died in 1893 in a cart accident while on his way to the land the government had given him.

Aftermath

In May 2013, at the tangi of MP Parekura Horomia, the Tuhoe iwi, who had initially supported Te Kooti and the rebel Hau Hau movement in their 19th century war against the government, gave a gift to Ngati Porou to end nearly 150 years of bitterness between the tribes. Ngati Porou had provided many of the soldiers who tracked down the guerilla leader in the late 1860s and had numerous conflicts with Tuhoe Hau Hau. During one conflict 120 Tuhoe Hau hau were captured and killed. Tuhoe leader Tu Waaka said he did not want successive generations to be encumbered by the events of the past.[57]

In fiction

- Maurice Shadbolt's novel Season of the Jew is set during Te Kooti's War

- The movie Utu is based very loosely around some incidents from Te Kooti's War

References

- Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars. Auckland: Penguin. p. 216. ISBN 0-14-027504-5.

- Binney, Judith (30 October 2012). "Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki". Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "The Mangatu Remedies Report" (PDF). Waitangi Tribunal. 23 December 2013.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 16, 21–22, 35. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 44–57. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 63–73. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 84–88. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- "Exile and Deliverance - Te Kooti's War". NZHistory.net. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 20 December 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 106–115. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 90–95. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars. Auckland: Penguin. pp. 221–226. ISBN 0-14-027504-5.

- Cowan, James (1922). "25, First engagements with Te Kooti". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, Vol. 2, 1864-72. Wellington: RNZ Government Printer.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 100–103. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Cowan, James (1922). "27, The Poverty Bay Massacre". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, Vol. 2, 1864-72. Wellington: RNZ Government Printer.

- "Matawhero - Te Kooti's War". NZHistory.net. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 20 December 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 121–129. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 131–135. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars. Auckland: Penguin. pp. 258–267. ISBN 0-14-027504-5.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 135–147. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars. Auckland: Penguin. pp. 232–233. ISBN 0-14-027504-5.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 151–181. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars. Auckland: Penguin. pp. 275–288. ISBN 0-14-027504-5.

- Dalton, B.J. (1967). War and Politics in New Zealand 1855–1870. Sydney: Sydney University Press. p. 270.

- Binney, Judith (2009), Encircled Lands: Te Urewera, 1820-1921, Bridget Williams Books, pp. 148–159, ISBN 978-1-877242-44-1

- McLean, Gavin (2013). "Armed Constabulary Boat". NZHistory.net. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- Cowan, James (1922). "33, The Surprise at Opepe". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, Vol. 2, 1864-72. Wellington: RNZ Government Printer.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars. Auckland: Penguin. pp. 280–281. ISBN 0-14-027504-5.

- "Te Kooti goes to Te Kuiti - Te Kooti's War". NZHistory.net. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 20 December 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Boast, Richard (2013), Ford, Lisa (ed.), Between Indigenous and Settler Governance, Routledge, pp. 78–80, ISBN 978-0-415-69970-9

- Dalton, B.J. (1967). War and Politics in New Zealand 1855-1870. Sydney: Sydney University Press. pp. 272–273.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 179, 595 footnotes 138–139. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Orange, Claudia (1987). The Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. p. 154. ISBN 086861-634-6.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 184–185. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Cowan, James (1922). "34, The Taupo Campaign". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, Vol. 2, 1864-72. Wellington: RNZ Government Printer.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 185–190. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- "Te Porere and retreat - Te Kooti's War". NZHistory.net. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 20 December 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 190–200. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars. Auckland: Penguin. pp. 284–288. ISBN 0-14-027504-5.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 200–208. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Cowan, James (1922). "35, Defeat of Te Kooti". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, Vol. 2, 1864-72. Wellington: RNZ Government Printer.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 209–214. ISBN 0-8248-1975-6.

- Cowan, James (1940). Sir Donald Maclean. Wellington: Reed Publishing. p. 102.

- "40". The New Zealand Wars: A History Of The Maori Campaigns And The Pioneering Period: Volume Ii: The Hauhau Wars, (1864–72) Te Kooti Defeated At Waipaoa. Early New Zealand Books (NZETC). 1939. pp. 432–446.

- Binney, Judith (2010). Encircled Lands: Te Urewera, 1820-1921. Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 9781877242441.

- "How Te Kooti Gained a Pardon", Historic Poverty Bay and the East Coast, Joseph Angus Mackay

- "The Main Trunk Railway", The New Zealand Railways Magazine

- Redemption Songs. p 312.

- Redemption Songs. p 384

- Redemption Songs. J Binney. Auckland University Press. 1996. pp 282-285.

- Redemption Songs. p 391-393.

- Redemption Songs. p 390.

- Redemption Songs. p 410.

- Redemption Songs. p 413.

- Waikato Times May 3, 2013

Literature and references

- Belich, James (1988). The New Zealand Wars. Penguin.

- Belich, James (1996) Making Peoples. Penguin.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs: A Life of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Crosby, Ron (2004). "Gilbert Mair, Te Kooti's Nemesis". Reed.

- Cowan, J., & Hasselberg, P. D. (1983) The New Zealand Wars. New Zealand Government Printer. (Originally published 1922)

- Maxwell, Peter (2000). Frontier, the Battle for the North Island of New Zealand. Celebrity Books.

- Simpson, Tony (1979). Te Riri Pakeha. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Sinclair, Keith (ed.) (1996). The Oxford Illustrated History of New Zealand (2nd ed.) Wellington: Oxford University Press.

- Stowers, Richard (1996). Forest Rangers. Richard Stowers.

- "The people of many peaks: The Māori biographies". (1990). From The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Vol. 1, 1769-1869. Bridget Williams Books and Department of Internal Affairs.

External links

- Te Kooti at Maori Independence website

- Te Kooti in 1966 An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

- Entry at history-nz.org

- Editorial objection to the pardon, Hawera & Normanby Star, 1883

- Te Kooti the Guerilla Fighter, James Graham

- Dictionary of New Zealand Biography.Te Kooti.Judith Binney

- Memorial to victims of 1868 Matawhero Massacre