Specifier (linguistics)

Under the X-bar theory of Syntax, phrases are formed of specifiers, head words, complements and adjuncts. Specifiers differ from complements and adjuncts because they are non-recursive, and phrases can only have one specifier.[1] The specifier of a phrase is the daughter of the maximal projection and the sister of an intermediate projection.

Theory 1: the Jackendovian specifier

Structural definition of specifier

In technical syntax terminology, the specifier of an XP is a YP that is the sister of X′, and the daughter of XP. The phrase structure rule is given by XP → (YP) X′, where YP is the specifier. The X-bar schema of this phrase structure can be seen in the tree diagram below (with XP corresponding to the maximal projection X″):

In recent transformational grammar, the term specifier is not normally used to refer to a type of word or phrase, but rather to a structural position provided by X-bar theory or some derivative thereof. In this usage, a phrase (usually a full XP, though in bare phrase structure it could in theory be an intermediate category) is said to occupy the specifier (SpecXP for short) of a head X.

Semantic definition of specifier

In English, some example of specifiers are determiners such as the, a, this, quantifiers such as no, some, every, and possessives such as John’s and my mother’s, which can precede noun phrases. Verb phrases can be preceded by quantifiers such as each, and all. Adjective phrases and adverbial phrases can be preceded by degree words such as very, extremely, rather and quite.[2]

These specifiers are so called because they further qualify the category of the head - in these examples nouns and adverbs - in the phrase.

For example:

- My friend likes [Jane Austen’s novels] - Jane Austen’s specifies novels in this noun phrase

- She is [quite certain of success] - quite specifies certain of success in the adverbial phrase quite certain of success

Different form classes can occupy a specifier position, typically determiners and possessors in noun phrases (N″), and an auxiliary verb in a verb phrase (V″).

Theory 2: the post-Jackendovian Specifier

Spec,CP

[Spec, CP] is a Wh-movement landing site. Wh-movement is moving the smallest XPwh to available CP specifier position[3] and XPwh mean question word or wh- (eg. who, what , when...). Wh-movement could raise XPwh to [Spec, CP] but it only moves under Subjacency Condition, that means if it violates Subjacency Condition then it will stop raising XPwh[4].

Example:

a) Lucy loves [DP2 cake].

b) [DP2 What] does Lucy love ___?

Spec,TP

[Spec, TP] is Extended Projection Principle (EPP) landing site. EPP moves the subject DP from [Spec, VP] to [Spec, TP] when the sentence is tensed.[5] Note that the subject is in [Spec, TP] in most sentences[1] but [Spec, TP] can have an object.

Example:

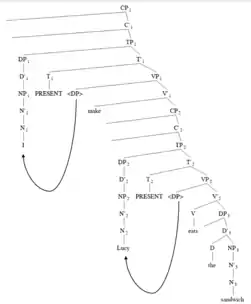

a) [CP [TP [DP Lucy ] will eat the sandwich ] ].

b) [CP1 [TP1 [DP1 I ] make [CP2 [TP2 [DP2 Lucy ] eat the sandwich ] ] ] ].

Spec,DP

In determiner phrase, possessive phrase DP is at DP specifier position the and possessive -'s is a determiner of the DP complement.

Example:

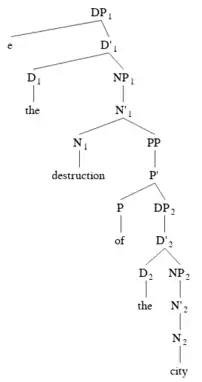

a) [DP The destruction of the city]

b) [DP [DP The city]'s destruction]

From these two examples, we can see that [DP the city] specifies [NP destruction] in example b). In contrast, example a) do not have any specifier but it has Preposition Phrase as NP complement.

References

- Carnie, Andrew (2013). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-470-65531-3.

- Sobin, Nicholas (2011). Syntactic Analysis: The Basics. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 104–13. ISBN 978-1-4443-3507-1.

- Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward. (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell.

- Ross, John Robert (1968). Constraints on variables in syntax. [Bloomington] : Linguistics Club, Indiana University.

- Chomsky, Noam (1982). Some Concepts and Consequences of the Theory of Government and Binding. Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press.

- Chomsky, Noam (1969). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-53007-1.