Special linear Lie algebra

In mathematics, the special linear Lie algebra of order n (denoted or ) is the Lie algebra of matrices with trace zero and with the Lie bracket . This algebra is well studied and understood, and is often used as a model for the study of other Lie algebras. The Lie group that it generates is the special linear group.

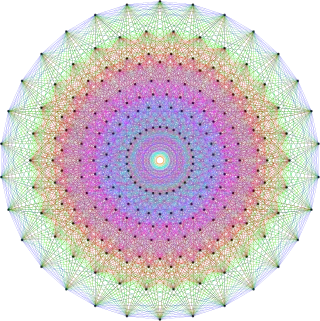

| Lie groups |

|---|

|

Applications

The Lie algebra is central to the study of special relativity, general relativity and supersymmetry: its fundamental representation is the so-called spinor representation, while its adjoint representation generates the Lorentz group SO(3,1) of special relativity.

The algebra plays an important role in the study of chaos and fractals, as it generates the Möbius group SL(2,R), which describes the automorphisms of the hyperbolic plane, the simplest Riemann surface of negative curvature; by contrast, SL(2,C) describes the automorphisms of the hyperbolic 3-dimensional ball.

Representation theory

Representation theory of

By definition, the Lie algebra consists of two-by-two complex matrices with zero trace. There are three standard basis elements, ,, and , with

- , , .

The commutators are

- , , and

The Lie algebra can be viewed as a subspace of its universal enveloping algebra and, in , there are the following commutator relations shown by induction:[1]

- ,

- .

Note that, here, the powers , etc. refer to powers as elements of the algebra U and not matrix powers. The first basic fact (that follows from the above commutator relations) is:[1]

Lemma — Let be a representation of and a vector in it. Set for each . If is an eigenvector of the action of ; i.e., for some complex number , then, for each ,

- .

- .

- .

From this lemma, one deduces the following fundamental result:[2]

Theorem — Let be a representation of that may have infinite dimension and a vector in that is a -weight vector ( is a Borel subalgebra).[3] Then

- Those 's that are nonzero are linearly independent.

- If some is zero, then the -eigenvalue of v is a nonnegative integer such that are nonzero and . Moreover, the subspace spanned by the 's is an irreducible -subrepresentation of .

The first statement is true since either is zero or has -eigenvalue distinct from the eigenvalues of the others that are nonzero. Saying is a -weight vector is equivalent to saying that it is simultaneously an eigenvector of ; a short calculation then shows that, in that case, the -eigenvalue of is zero: . Thus, for some integer , and in particular, by the early lemma,

which implies that . It remains to show is irreducible. If is a subrepresentation, then it admits an eigenvector, which must have eigenvalue of the form ; thus is proportional to . By the preceding lemma, we have is in and thus .

As a corollary, one deduces:

- If has finite dimension and is irreducible, then -eigenvalue of v is a nonnegative integer and has a basis .

- Conversely, if the -eigenvalue of is a nonnegative integer and is irreducible, then has a basis ; in particular has finite dimension.

The beautiful special case of shows a general way to find irreducible representations of Lie algebras. Namely, we divide the algebra to three subalgebras "h" (the Cartan Subalgebra), "e", and "f", which behave approximately like their namesakes in . Namely, in an irreducible representation, we have a "highest" eigenvector of "h", on which "e" acts by zero. The basis of the irreducible representation is generated by the action of "f" on the highest eigenvectors of "h". See the theorem of the highest weight.

Representation theory of

When for a complex vector space , each finite-dimensional irreducible representation of can be found as a subrepresentation of a tensor power of .[4]

Notes

- Kac 2003, § 3.2.

- Serre 2001, Ch IV, § 3, Theorem 1. Corollary 1.

- Such a is also commonly called a primitive element of .

- Serre 2000, Ch. VII, § 6.

References

- Etingof, Pavel. "Lecture Notes on Representation Theory".

- Kac, Victor (1990). Infinite dimensional Lie algebras (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46693-8.

- Hall, Brian C. (2015), Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 222 (2nd ed.), Springer

- A. L. Onishchik, E. B. Vinberg, V. V. Gorbatsevich, Structure of Lie groups and Lie algebras. Lie groups and Lie algebras, III. Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, 41. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1994. iv+248 pp. (A translation of Current problems in mathematics. Fundamental directions. Vol. 41, Akad. Nauk SSSR, Vsesoyuz. Inst. Nauchn. i Tekhn. Inform., Moscow, 1990. Translation by V. Minachin. Translation edited by A. L. Onishchik and E. B. Vinberg) ISBN 3-540-54683-9

- V. L. Popov, E. B. Vinberg, Invariant theory. Algebraic geometry. IV. Linear algebraic groups. Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, 55. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1994. vi+284 pp. (A translation of Algebraic geometry. 4, Akad. Nauk SSSR Vsesoyuz. Inst. Nauchn. i Tekhn. Inform., Moscow, 1989. Translation edited by A. N. Parshin and I. R. Shafarevich) ISBN 3-540-54682-0

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (2000), Algèbres de Lie semi-simples complexes [Complex Semisimple Lie Algebras], translated by Jones, G. A., Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-67827-4.