Sophia Wells Royce Williams

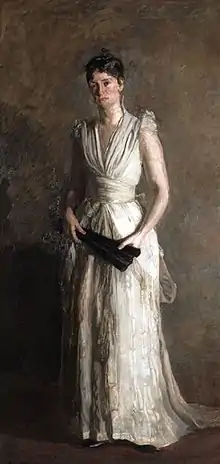

Sophia Wells Royce Williams (1850 – 1928) was an American civic activist, philanthropist, and photographer, who with her husband, Talcott Williams, donated a substantial collection of Moroccan ceramics and other materials to the Smithsonian Institution and the Penn Museum. She was the subject of a Thomas Eakins portrait, entitled The Black Fan, now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[1]

Origin and Family

Sophia Wells Royce was born in 1850 and grew up in Albion, New York. Her father was Julius H. Royce,[2] a one-time director of the Niagara River and New York Airline Railroad.[3] Her mother, Harriette A. Wells Royce, came from New Bedford, New York and attended Mount Holyoke College.[4]

On May 28, 1879 Sophia Wells Royce married a distant cousin, Talcott Williams, who was born in Abeih, near Beirut. She was a newspaper reporter at the time of her marriage.[5] Talcott Williams was the son of William Frederic Williams and Sarah Pond Williams, missionaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.[6] A graduate of Amherst College, Talcott Williams was a journalist and went on to become first director of the Columbia School of Journalism.[7] His portrait, also by Thomas Eakins, is now in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.[8]

In 1881, Sophia Wells Royce Wiliams moved with her husband to Philadelphia.[9] Together Sophia and Talcott Williams moved in a social circle that included many prominent Philadelphia artists, writers, and thinkers, including Thomas Eakins, Eadweard Muybridge, Cecilia Beaux, Horace Howard Furness, and others.[10]

Sophia Wells Royce Williams became an active member of the Civic Club in Philadelphia and in 1895 ran for a position on the school board of Philadelphia's Seventh Ward. She was also secretary for many years of the Contemporary Club, a society in Philadelphia that gathered men and women who were interested in the arts and in social and political issues of the day.[11]

Political Activism

In 1895, the Civic Club in Philadelphia circulated to the Municipal League and to city newspapers the names of women who were willing to serve as School Directors, if supported by the Republican and Democratic leadership. The Municipal League responded by nominating two women, including Sophia Wells Royce Williams, for the Seventh District, which roughly corresponded to today's Society Hill neighborhood. The Civic Club organized a campaign committee which promoted the two women; the committee then organized a widespread canvass of eligible voters. In spite of their involvement, neither secured the election.[12] Her effort to run for the school board reflected what historians have called the “social housekeeping” movement of the period which represented an early foray for women into electoral politics.[13]

Museum Donations

Sophia Wells Royce Williams and her husband Talcott Williams traveled to Morocco from 1897 to 1898 and collected hundreds of objects which they donated to the Penn Museum.[14] In 2020, fifteen of these objects were on public display. Some of the objects are pottery created in the 1890s that feature ornate, blue patterning and a shiny glaze. The collection also includes wooden carvings, clothing, food containers, Arabic manuscripts, woven baskets, and more.[15]

During the same expeditions, Sophia Wells Royce Williams and Talcott took photographs and collected objects which they donated to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Currently, the Smithsonian Institution's onine catalogue attributes 280 objects in its collections to Talcott Williams. The Smithsonian does not cite Sophia Wells Royce Williams who also collected and donated the objects.[16]

Criticism of Clara Barton and the American Red Cross

In The Review of Reviews, a progressive reformist journal that flourished in the 1890s in British and American editions, Sophia Wells Royce Williams published an article in 1894 on “Miss Clara Barton and the Red Cross.” Williams traced the history of what became the American Red Cross by discussing Barton's efforts, during the U.S. Civil War, to collect and distribute money and stores for wounded soldiers, including her own brother. After the war, Barton expanded efforts of the Red Cross into general disaster relief, helping U.S. communities from California in the west to the Carolinas in the east that were struck by events like earthquakes, droughts, and hurricanes.[17]

While Williams applauded Barton's success in securing the support of the U.S. president and Congress for ratification of the Geneva Convention, and while she praised Barton's efforts to secure large donations to sustain the work of the Red Cross in the United States, Williams criticized Barton's total domination of the society. In her words, “Miss Clara Barton has been the National Red Cross Society” (p. 314).[17] Williams also criticized Barton's lack of organization, record-keeping, and transparency in management of funds. Williams concluded that the ideal Red Cross would be governed by a board of men, including male surgeons, doctors, military officials, and business leaders like “Pierrepont Morgan” (John Pierpont Morgan).[17]

Photography and Friendship with Eakins and Whitman

In Philadelphia, Sophia Wells Royce Williams and her husband Talcott Williams were close friends of the artist Thomas Eakins, who painted both of them. The Philadelphia Museum of Art preserves the oil painting called The Black Fan: Portrait of Mrs. Talcott Williams. Eakins displayed the painting to acclaim but never finished it; according to the art historian Carolyn Kinder Carr, Sophia Williams refused to continue sitting for him “after a male visitor to the studio had departed [and…] Eakins poked her in the stomach and told her she could relax.”[10]

The Williamses were also close friends with the poet Walt Whitman, whom they knew from as early as 1882. They visited Whitman often during the last years of his life, when he was living in Camden, New Jersey. Talcott Williams introduced Thomas Eakins to Whitman, and Eakins went on to paint Whitman's portrait.[10]

Possibly because of Eakins's fame and known acquaintance with Whitman, many scholars used to ascribe a portrait photograph of Whitman to Eakins. The discovery of a new copy of this photograph in 1986 confirmed the claims of descendants of Talcott Williams's sister, Cornelia Williams Chambers, that Sophia Wells Royce Williams, and not Eakins, had been the photographer.[10]

In a study of this photograph, published in 1989, Carolyn Kinder Carr, a curator in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, assembled archival and material evidence (including signatures on copies of the portraits) to confirm that Sophia Wells Royce Williams was the photographer of Walt Whitman's portrait. Among the significant pieces of evidence are records in the Library of Congress, from an exhibit that it held in 1955, showing that Williams had registered copyright for this image in 1896. Carr notes that this famous image of Whitman, which shows the aged poet seated near a window, “cannot be considered a great photograph from an aesthetic point of view", but notes its significance as one of the only images of Walt Whitman from the final years of his life. Among the institutions that preserve copies of Sophia Wells Royce Williams's famous photograph of Walt Whitman, are the Library of Congress, the Yale Beinecke Library, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University.[10]

Carr also found archival evidence, including correspondence from Talcott and Sophia to each other, showing that Sophia Wells Royce Williams was a proficient photographer, interested in camera equipment, and aware of their technical requirements and artistic capacities. Carr suggested that the Williams's may have developed some awareness of this medium through their long friendship with Eadward Muybridge, who pioneered studies of animal locomotion and who was also affiliated with the museum at the University of Pennsylvania.[10][18] Sophia Williams took many photographs during the couple's trips to Morocco; the Smithsonian Institution preserves seventy-five of them.

References

- Eakins, Thomas (1891). "The Black Fan, Portrait of Mrs Talcott Williams". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Marquis, Albert Nelson (1908–1909). Who's Who in America. Chicago: A.N. Marquis. p. 2073.

- "Albion Entrepreneur Partnered with George Pullman | Orleans County Department of History". Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Society, Mount Holyoke Female Seminary Memorandum (1867). Catalogue of the Memorandum Society, of Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, for Thirty Years, Ending 1867.

- "Talcott Williams of Columbia Dead" (PDF). The New York Times. January 25, 1928. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Staff, New England Historic Genealogical Society (April 1996). The New England Register,: Volume 34 1880. Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-0431-3.

- "Search results for: Williams, Talcott, Catalog cards, page 1 | Collections Search Center, Smithsonian Institution". collections.si.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Eakins, Thomas Cowperthwaite (c. 1889). "Talcott Williams". National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- "Philadelphia Museum of Art - Collections Object : The Black Fan (Portrait of Mrs. Talcott Williams)". www.philamuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Carr, Carolyn Kinder (1989). "A Friendship and a Photograph: Sophia Williams, Talcott Williams, and Walt Whitman". American Art Journal. 21 (1): 3–12. doi:10.2307/1594519. ISSN 0002-7359. JSTOR 1594519.

- "Contemporary Club (Philadelphia, Pa.) records 1981". www2.hsp.org. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Philadelphia, Civic Club of (1895). The Story of a Woman's Municipal Campaign by the Civic Club for School Reform in the Seventh Ward of Philadelphia. American academy of political and social Science.

- Gustafson, M.S. (2011). "Good City Government is Good Housekeeping: Women and Municipal Reform". Pennsylvania Legacies. 11:2.

- "My Finds list". Penn Museum. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Pezzati, Alex (2012). "Moroccan Pottery in the African Collection". Expedition. 54:3: 27.

- Carr, Carolyn Kinder (1989). A Friendship and a Photograph: Sophia Williams, Talcott Williams, and Walt Whitman. The American Art Journal. pp. 2–12.

- Williams, Sophia Wells Royce (1894). "Miss Clara Barton and the Red Cross". The Review of Reviews: 312–316.

- Gordon, Sarah Anne (2015). Indecent Exposures: Eadweard Muybridge's Animal Locomotion Nudes. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0300209488.