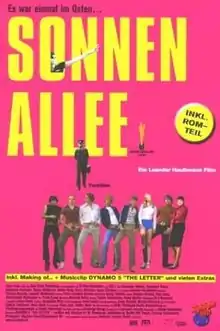

Sonnenallee

Sonnenallee (Sun Avenue or Sun Alley[1]) is a 1999 comedy film about life in East Berlin in the late 1970s. The movie was directed by Leander Haußmann. The film was released shortly before the corresponding novel, Am kürzeren Ende der Sonnenallee (At the Shorter End of Sonnenallee). Both the book and the screenplay were written by Thomas Brussig and while they are based on the same characters and setting, differ in storyline significantly. Both the movie and the book emphasize the importance of pop-art and in particular, pop music, for the youth of East Berlin. The Sonnenallee is an actual street in Berlin that was intersected by the border between East and West during the time of the Berlin Wall, although it bears little resemblance to the film set. Sonnenallee was broadcast in the Czech Republic under the title Eastie Boys.[2]

| Sonnenallee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Leander Haußmann |

| Produced by | Claus Boje |

| Written by | |

| Starring |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Language | German |

Cast

- Alexander Scheer as Michael "Micha" Ehrenreich

- Alexander Beyer as Mario Naujoks

- Robert Stadlober as Wuschel

- David Mueller as Brötchen

- Teresa Weißbach as Miriam Sommer

- Katharina Thalbach as Doris Ehrenreich

- Henry Hübchen as Hotte Ehrenreich

- Elena Meißner as Sabrina

- Detlev Buck as Sergeant (Major) Horkefeld

- Winfried Glatzeder makes a brief cameo appearance, reprising his role as Paul from the East German film The Legend of Paul and Paula.

Plot

Michael "Micha" Ehrenreich (Scheer) is a 17-year-old growing up on Sonnenallee on the East German side of the street in Berlin in the 1970s. Micha and his friends enjoy contraband records, cassette tapes, and other pop culture. While listening to the newest tape Micha has ripped, Sergeant Major Horkefeld, the neighborhood's overzealous policeman, approaches them and confiscates the tape, but announces he is going to make himself a copy. Micha then spies Miriam for the first time and is spellbound. Shortly after, Heinz, Micha's smuggler uncle from the West, visits and harangues Micha over his intention to join the National People's Army. Later, at a disco, Micha tries to dance with Miriam, but she is more interested in her West German boyfriend, who is thrown out of the disco by the overzealous sergeant major. For allowing a West German into the disco, Miriam is made to deliver a self-critical lecture at the next meeting of the Free German Youth.

At school the next day, Mario (Beyer) vandalizes a sign in their classroom, but Micha claims responsibility in order to win over Miriam with a self-critical lecture of his own. After the lecture, Mario berates Micha for getting into "the system" for the sake of a woman. Micha then sees Horkefeld, who has been demoted to Sergeant for playing contraband music in the presence of a higher officer at a party. At a black market gathering, Mario meets Sabrina, an existentialist, and feigns an interest in Sartre in order to sleep with her. After a run-in with Mr. Fromm, a sinister-looking neighbor thought by the entire apartment to be a Stasi agent, Micha's father, Hotte, reveals that he has been provided a telephone due to a chronic illness. Miriam phones Micha, who runs to a pay phone in order to have more privacy. Having forgotten his ID card, he is hauled in by Horkefeld and held for over ten hours.

That night, Mario hosts a party at his parents' house, as they are gone for the weekend. Fueled by drugs, the party becomes raucous, and Micha and Mario escape to the balcony, where they are photographed urinating onto the border wall below. Miriam arrives to a chaotic scene, and leaves after encountering a stoned Micha, who claims that he has written many diaries about his feelings toward Miriam. The next day, Micha and Mario are called into their headmistress' office, where a Stasi agent informs the pair that the photographs of them urinating on the Berlin Wall made it into West German press. The headmistress berates the pair for disrespecting the sacrifices of the country, and strips Micha of his student stipend, expelling Mario entirely. No longer tied to the city, Mario and Sabrina begin to journey through the East German countryside. Micha sees Miriam, who reminds him that he promised to let her read his diaries. Caught in his lie, Micha goes home and begins to write many years' worth of diaries. Doris, Micha's mother, carries out a plan to defect to the West using a stolen passport and makeup, but changes her mind at the border station.

Some time later, Heinz returns, and is pulled aside by a border guard who shows him confiscated material. While plugging in a Japanese stereo, which uses different voltage amounts, the guard overloads the power grid and knocks the street into darkness. Among the chaos, Sabrina confides in Mario that she is pregnant, and Micha's young friend Wuschel makes a run for the border. He is shot by Horkefeld, but the copy of Exile on Main St. he is carrying stops the bullet. Discovering the record has shattered, he is heartbroken.

Nearing the end of his diary forgeries, Micha has a sudden realization about his political beliefs, and reneges on his promise to join the army. As he is leaving, he sees Mario at the recruitment station, who confesses that he is joining the army to provide for his new child. Micha grows outraged, and the two scuffle. When Micha returns home, he discovers Heinz – who always claimed the asbestos in East German dwellings would kill someone – dead of lung cancer. Here, the family discovers that Fromm is not a Stasi agent, and works for a funeral company instead. Doris is allowed back into the West for his funeral, and smuggles his ashes back in a coffee can in order to bury him with their mother. Micha goes to Miriam's house and delivers her the diaries, as her now ex-boyfriend waits outside, growing impatient. As he exits his car, he hits Wuschel with the door and bribes him not to talk to the police. While Micha and Miriam share an intimate moment, the Westie is stopped at the border with a trunk full of weapons. With border guards pointing weapons in his face, he reveals that his fancy cars come from the hotel where he serves as a valet.

Back in Micha's room, he and Wuschel listen to the new Exile On Main St. album purchased by Wuschel with his bribe money. They discover that the black market salesman has forged the album, but play air guitar to it on the balcony in front of a crowd of people, including a now-jobless Horkefeld, newly-married Mario and Sabrina, and the rest of the characters. The film ends with the crowd massing at the border, followed by a long black and white shot of the border gates opened and the street abandoned.

Controversy

Writing for Der Spiegel, Marianne Wellershoff argued that the film glorified the GDR and played down the negative aspects of life in East Germany under Erich Honecker.[3] But other reviewers saw this criticism as unfair, and the film was well received by German viewers.[4][5]

Further reading

Preuss, Evelyn. "The Wall You Will Never Know" . Perspecta 36: The Yale Architectural Journal. Eds. Jennifer Silbert and Sidney McCleary. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005: 19-31.

References

- Sonnenallee at IMDb

- "Eastie Boys". Česko-Slovenská filmová databáze (in Czech).

- Wellershoff, Marianne (4 October 1999). "Sonnenallee: Musik der Freiheit" [Sun Alley: Music of Freedom]. Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- de Wit, Elke (6 March 2000). "The Sunnier Side of East Germany". Central Europe Review. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- Cassidy, Tim. "Sonnenallee". CultureVulture. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

External links

- Sonnenallee at IMDb