Sojourner Truth Project

As a strikingly controversial project in 1941, Sojourner Truth Project (alternately named the Sojourner Truth Project) set precedents for Detroit housing project policy through the next decade. Created by the Detroit Housing Commission (DHC) and United States Housing Authority (USHA), the proposed two-hundred-units would alleviate housing shortages caused by the wartime climate of World War II. However, the project was met with extreme backlash from white residents and middle-class black homeowners in Conant Gardens.[2] Violence erupted in 1942 when black families moved into the project housing. More than a thousand black supporters and white opponents crowded streets culminating in violent displays later characterized as the Sojourner Truth riot. White racists opposed to integrated public housing exploited the riot's sensationalized violence to manipulate policy makers to oppose future projects.[1]

| Sojourner Truth Homes | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Residential |

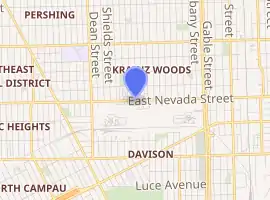

| Address | 4801 E. Nevada, 48234 |

| Town or city | Detroit, Michigan |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 42°25′34″N 83°03′19″W |

| Groundbreaking | 1941 |

| References | |

| [1] | |

History

In 1941, during World War II, the DHC and USHA announced the Sojourner Truth project located in northeast Detroit at the heart of Seven Mile-Fenelon neighborhood. The location was purposely chosen because of its proximity to existing concentrations of black communities in an attempt to circumvent controversy. The 200 proposed units acted to alleviate wartime housing shortages.

Resident reactions

Backlash

White residents, outraged by public housing projects for impoverished and oppressed Blacks, adamantly opposed the Sojourner Truth project. The Seven Mile-Fenelon Improvement Association, formed by white residents between June 1941 and February 1942, viciously opposed the project's fruition. Black middle class residents of Conant Gardens perpetuated the visceral housing oppression of impoverished Blacks by briefly aligning their values and efforts with the improvement association' opposition to the project.[3] Residents showcased their antipathy through regular meetings, protests, picket lines at city officers, thousands of angry letters, meetings with city officials, attendance of Common Council meetings, and lobbying congressmen in opposition to the public housing.

Support

The Sojourner Truth project, however, found dedicated support from civil rights groups, left-leaning unionists, and pro-public housing groups. The supporters pressured government officials to provide the necessary black housing proposed by the project.[1]

Influence

The continual pressure from opposing sides influenced the Federal Government to switch positions on the racial profile of those occupying the project three times. Original proposals of black occupancy resulted in the Federal Housing Administration's (FHA) refusal to insure mortgage loans for the Seven Mile-Fenelon because of its proximity to the public housing. The racist FHA policy instilled in white residents fears that black residence would directly result in their inability to finance new construction on vacant lots or personal improvement projects.[4][5] Bending to white pressure, in January 1941, the DHC designated the Sojourner Truth as a project of white occupancy. After a subsequent eruption of two week long protests, city officials promised the project to black war workers. However, this resulted in opposing picketing and protesting by white residents of Seven Mile-Felon who demanded "Rights to Protect, Restrict and Improve [their] Neighborhood." However, black families moved into the newly constructed housing on February 28, 1942.[6]

Sojourner Truth riot

On February 28, 1942, as the first black families moved into their houses, black supporters and white opponents flooded the streets by the thousands. Passionate protest turned to visceral violence as 40 people were injured, 220 arrested, and 109 held for trial—all but three were black. White segregists utilized this violent eruption as an established precedent to detrimentally affect Detroit's public housing for decades. Influenced by the riot, DHC established a viciously oppressive mandate for racial segregation in all public housing projects. Utilizing the language of the National Associate of Real Estate Boards, city officials vowed that their projects would "not change the racial pattern of a neighborhood".[7] White community groups maliciously utilized threats of a repetition of Sojourner Truth Riots as ammunition to shoot down political support of public housing. City officials strongly wanted to avoid bloodshed and therefore surrendered to their elitist demands.[1]

Later impacts

The controversy of the Sojourner Truth project continued into 1944 with the proposal of a three-hundred-unit housing expansion. However, the DHC rejected the proposal out of belief that it "would be inviting a major controversy while gaining only a very small percentage of the houses needed to solve the immediate housing problem".[8] However, 250 black families successfully moved into the Sojourner Truth housing contrasting the starkly incremental trickle of black occupancy in other parts of the neighborhood. Although representative of racial movements, the transitions of families into the area continued to support the racial divide defined by the Eight-Mile wall that perpetuated systematic and racist housing oppression. Blacks moved into the area between Conant Gardens and the Sojourner Truth or eastern blocks—showcasing this vicious divide.[9]

References

- Sugrue, Thomas J. (1996). The origins of the urban crisis: race and inequality in postwar Detroit. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069101101X. OCLC 34472849.

- Capeci. Race Relations in Wartime Detroit. pp. 75–99.

- Clive, Alan (1979). "State of War: Michigan in World War II". Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Capeci. Race Relations in Wartime Detroit. p. 80.

- Abrams, Charles (1955). Forbidden Neighbors: A Study of Prejudice in Housing. New York. p. 95.

- Capeci. Race Relations in Wartime Detroit. p. 88.

- Jenkins. The Racial Policies of the DHC. p. 21.

- Abrams. Forbidden Neighbors. pp. 99–101.

- 1950 Census, tract 603; 1960 Census, tracts 603A, 603B.