Small heath (butterfly)

The small heath (Coenonympha pamphilus) is a butterfly species belonging to the family Nymphalidae, classified within the subfamily Satyrinae (commonly known as "the browns"). It is the smallest butterfly in this subfamily. The small heath is diurnal and flies with a noticeable fluttering flight pattern near the ground. It rests with closed wings when not in flight.[3][4][5] It is widespread in colonies throughout the grasslands of Eurasia and north-western Africa, preferring drier habitats than other Coenonympha, such as salt marshes, alpine meadows, wetlands, and grasslands near water (i.e. streams).[6][7][8] However, habitat loss caused by human activities has led to a decline in populations in some locations.[4]

| Small heath | |

|---|---|

_P.jpg.webp) | |

| In Poland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Nymphalidae |

| Genus: | Coenonympha |

| Species: | C. pamphilus |

| Binomial name | |

| Coenonympha pamphilus | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The larval host plants are grasses, found in various habitats, while adult butterflies feed on nectar from flowers.[9][10] The males of this species are territorial, which plays a large role in obtaining a female mate. To establish dominance, they partake in lekking, a mating display in which males aggregate in a competitive display to attract passing females.[11]

Taxonomy

The small heath is one of 40 species classified within the genus Coenonympha and placed in the family Nymphalidae. It belongs to the tribe Satyrini and its Coenonymphina subtribe.[12] The small heath was first described in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist and zoologist, in his book Systema Naturae.[13] Originally, the female C. pamphilus butterfly was referred to as the Golden Heath Eye and the male as the Selvedged Heath Eye. Entomologist Moses Harris later described it as the Small Heath or the Gatekeeper. However, the Gatekeeper now describes the Pyronia tithonus.[14]

Description in Seitz

C. pamphilus. Small butterflies which on the upper side are the colour of reddish yellow sand. Forewing beneath reddish yellow, bordered with grey and bearing a small pupilled apical ocellus; hindwing diluted with grey, with a shortened, curved, whitish median band shaded with brown. The ocelli are generally completely absent or only indicated by faint and indistinct vestiges of dots or rings. — The ground-colour of the hindwing of the Northern form, pamphilus L. (= nephele Hbn., menaleas Poda, gardetta Loche) (48 g) is mouse grey beneath; it is the only form in the North, and extends throughout North and Central Europe to Anterior Asia, Turkestan, Ferghana and Persia. — In ab. bipupillata Cosm. the apical ocellus is greatly enlarged and doubly pupilled. — marginata Stgr. (48 g) has a very broad dark distal margin on all the wings, but its underside resembles that of lyllus. (A broadening of the blackish distal margin occurs in the summer brood in many localities.) — lyllus Esp. is the summer form from Southern Europe, North Africa and the southern part of Anterior Asia. In this form the wings are broader, the apex of the forewing is more rounded, the margin of the hindwing often undulating, the underside of the hindwing not mouse-grey but also sandy yellow with a fine, curved, median line. — In thyrsides Stgr. (48 g), from Sicily-, Dalmatia and the southern portion of Anterior Asia, of which I also found typical specimens in the valleys of the Atlas, the hindwing on both sides bears a submarginal row of ocelli, which are sometimes pupilled. — Larva bright green with a thin, double, white dorsal stripe and yellow lateral one. Head pale green; throughout the summer on grasses.Pupa stout, green, with darker markings. The butterflies are the commonest Satyrids in the whole of Europe and are on the wing from the end of April until October, everywhere on meadows and fallow fields, cornfields and bare summits of hills. They almost fly only when disturbed, and soon settle again, affecting roads and bare patches of ground, sometimes inclining their always closed wings to one side. Their flight is jumping, slow, and low. They even fly into the towns, wandering over gardens and yards, and one sometimes sees them hopping along on paved streets for traffic, and settling for a moment on the pavement.[15]

Subspecies

Subspecies of the Coenonympha pamphilus include:[16][17]

- C. p. lyllus (Esper, 1806) (southern Europe and Siberia, the Crimea, the Caucasus and Transcaucasia)

- C. p. marginata Heyne, [1894] (southern Europe and Siberia, the Crimea, the Caucasus and Transcaucasia)

- C. p. fulvolactea Verity (1926) (middle Asia)

- C. p. centralasiae Verity (1926) (middle Asia)

- C. p. infrarasa Verity (1926) (middle Asia)

- C. p. juldusica Verity (1926) (middle Asia)

- C. p. ferghana Stauder (1924) (middle Asia)

- C. p. nitidissima Verity (1924) (middle Asia)

- C. p. asiaemontium Verity (1924) (Altai Mountains)

- C. p. rhoumensis Harrison (1948)

Similar species

The butterfly loosely resembles a small meadow brown, but the brown of the wings appears noticeably paler in flight. Unlike the meadow brown and other common members of the subfamily Satyrinae, the small heath is a lateral basker, only ever resting with its wings closed and angled at 90° to the sun.[18] It more closely resembles Coenonympha caeca (forewing without apical spots), Coenonympha tullia (forewing apical spot smaller), and Coenonympha symphita (underside of hindwing without white spot and almost always with a complete row of spots on the forewing).[19]

Distribution and habitat

The small heath is spread throughout the Western Palearctic, particularly in Europe where it has been reported in at least 40 different countries since 2002.[20][21] It is commonly found in the United Kingdom, largely in England and Wales. Populations are also found in southwest Siberia, regions of Asia, and north Africa.[14]

As a grasslands species, the small heath prefers open habitats with shorter grass compared to other related species. It is also found in an extensive range of environments including meadows, heaths, mountains (in the subalpine zone), and alongside railways.[3][22] It has been sighted in calcareous grasslands throughout nineteen countries in Europe.[20][23] For mating and oviposition, small heath butterflies prefer territories that are close to vegetation over areas that are open and clear.[22]

The small heath also resides in biodiverse patches of green habitats (i.e. greenways, gardens, and parks) in urban areas. These fragments create less-isolated corridors throughout cities, which help butterflies disperse throughout this habitat.[24]

Food resources

Caterpillars

The primary food resources for small heath larvae are different varieties of grass species. These include the Anthoxanthum odoratum, Poa pratensis, Agrostis stolonifera, and Festuca rubra, which commonly appear on some calcerous grasslands.[21][9]

Adults

.jpg.webp)

Adult small heath butterflies feed on floral nectar of a variety of flowers such as bramble, yarrow, and ragwort.[3] This nectar has a high content of minerals and nutrients (particularly amino acids and sugar), and is highly important for male and female butterfly reproductive success.[10]

Parental care

Oviposition

The small heath is a plurivoltine butterfly, having multiple generations in a year.[25] Oviposition varies throughout the lifespan of a female small heath. The rate of oviposition is high for young females, particularly at the beginning of their reproductive life, while older females eventually lay fewer and yellower eggs.[26]

Host plant selection for egg laying

Small heath females prefer to lay eggs in grassland.[3] They use a biological adhesive to lay its eggs directly onto host plants, plants near host plants, or wilting leaves. If the eggs are laid on or near host plants, the larvae are able to feed on the host plant. If attached to the dead grasses, they are forced to find their own food immediately after hatching.[27]

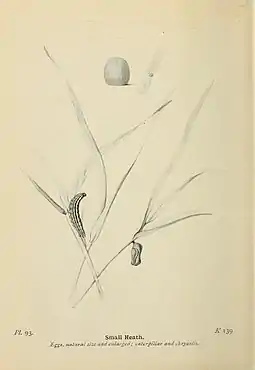

Life cycle

Eggs

Small heath eggs are round and sometimes laid on blades of grass. The eggs are occasionally in clusters, but usually alone. Initially, the egg is a light green with a slight depression on the top and an overall ridged texture. It later gains a white hue with a brown band wrapped around the middle and irregular brown speckles on the surface.[14]

Egg color and weight changes throughout a female's lifespan. Younger females initially tend to lay heavier, greener eggs at a higher frequency. These eggs then transition to an intermediate green-yellow color. After about 100 eggs are laid, or near the end of their lifespans, older females lay lighter, yellow eggs.[26] Adult small heath butterflies have at least one or usually two broods of offspring depending on environmental factors (such as location and altitude).[21]

Larvae

Butterflies like the small heath typically undergo multiple stages of development called instars, through which the insect grows noticeably larger in size. The small heath typically goes through four instars and molts three times. The third instar signals a diapause in which the larva hibernates. By the end of the fourth instar, the small heath larvae are a leafy green color with a green stripe running along its back and stripes a lighter shade of green on its sides. It has pink anal points, a protrusion at the end of the caterpillar. Larvae will sometimes undergo a fifth instar and enter diapause, which possibly signals an adapted response to environmental factors (primarily temperature). In diapause, the larva's resources are used to reinforce and strengthen its already-existing larval adult structures. These larvae then develop into larger male and smaller female pupae.[21][14]

Pupae

The small heath remains in the pupae stage for approximately 3 weeks. The color of the chrysalis fully develops in four days. The pupa is light yellow-green and suspends from a plant stem with the head facing downward. The cremaster is a series of hooks at the rear of the pupa, which allows it to hang from the stem. The pupae is thick and has a length of 8.5 mm. It is slightly curved with dark dorsal stripes around the sides and light-yellow bumps on the abdomen. The wing covers along the side are a white pigment with small accents of red-brown.[3][14]

Adult

The wings of an adult small heath butterfly are light brown. Males are darker and sometimes have gray-brown hues, while females are paler and occasionally a white-brown or yellow-white color. Other variations include a redder or yellower pigment with the occasional purple-brown color. Both males and females can have a brownish-gray border circling the edge of the wing. This border varies in thickness and appears to be more common in males than in females. The forewing can have a prominent or faint dark spot or, sometimes, no spot at all near the wing tip. The hindwings may also have eyespots or white dots. A white band runs along the underside of the wing and varies in width and fullness.[14] Female small heath butterflies have a wingspan of 37 mm and tend to be larger than males, which have a wingspan of 33 mm.[3]

The small heath is diurnal, or is active in the daytime. It flies near the ground with a fluttering flight pattern.[5] Small heaths are also lateral baskers, angling their bodies 90° to the sun with their wings closed when resting.[18]

A brown variation in wing pattern

A brown variation in wing pattern.jpg.webp) A yellow variation in wing pattern

A yellow variation in wing pattern_underside_Italy.jpg.webp) showing dark spots on rear wing underside

showing dark spots on rear wing underside

Mating

Aggression between males

Male small heath butterflies often establish their own territories and become stationary. Males with their own territories are more likely to mate successfully with females. This prompts aggressive male behavior between stationary males and wandering males who may contest territory ownership. The stationary male sometimes engages the wandering male in an attempt to determine its sex, and these interactions remain short to reduce vulnerability to predation. Longer interactions between males are typically territorial disputes. Larger males are typically more successful in territorial disputes with other males, as they have longer wing spans and are superior in size and weight to smaller males. Thus, larger males have a significantly higher chance of successfully mating a female.[22]

Temperature plays a role in male-male interactions as well. Both females and males increase vagrancy with increased temperatures, and vice versa. In low-temperature conditions, it is advantageous for a male to remain stationary in order to defend his territory as a potential mating site. This leads to longer male-male interactions when territorial disputes are more likely to occur. However, when temperatures are high, choosing not to defend territory is the preferred and advantageous strategy in mating. This is because males who become vagrant will have a higher chance of intercepting a wandering female in competition with other vagrant males. This leads to shorter male-male interactions as males are not defending territory.[3][5][22]

Interactions between males and females

Mate choice

Male small heath butterflies find mates either by defending their ownership of a territory or by drifting in search for a female. Virgin females also spend time in the air to find a potential mate, but females who have already mated avoid claimed territories. Due to its longer lifespan, virgin females seek mates less urgently than, for example, females of the C. tullia species. Virgin small heaths females will allow males to pass by instead of seeking them out to begin courtship. They choose to perform a long, elaborate zig-zag flight pattern to draw attention after they reach a group of perching males, who will take part in lekking as a show of dominance. The female then selectively chooses her mate and begins a monandrous relationship.[11] Most matings occur with residents within territories than with the wandering non-residents. Females often mate with males with larger wings, as territory owners are usually larger, and generally mate only once or twice in their short overall lifetimes.[3][22]

Lekking

Male small heaths aggregate and form leks often around bushes or trees, creating an elaborate visual display to attract a female's attention. The female will approach by circling the lek, which attracts the males' attention more than being stationary. There are both costs and benefits of lekking for the female. Females benefit by typically mating with the dominant male and producing offspring with beneficial, heritable genes, as a result of their free choice in mates. They also have increased survival and maintained health because males cannot force the females to copulate. A few fitness costs include lost time to obtain more resources, risk of mortality through predation, and less time for oviposition, which all lead to decreased fecundity. The leks themselves do not contain resources for the females.[28]

Copulation

Copulation between male and female small heath butterflies lasts between 10 minutes and 5 hours, occurring at any time in the day.[3] In 1985, a study observed that males often mate within their own territory (86.7% of 30 matings), and these copulations are generally lengthy, lasting over 100 minutes. Otherwise, copulations lasted approximately 10–30 minutes, especially for vagrant males. The study also found that either the male or female (but generally the male) is forced to leave the territory after copulation.[22]

Nuptial gifts

During copulation, male small heath butterflies transfer a nuptial gift to a female in the form of a spermatophore, which contains both additional nutrients and sperm. Males can use amino acids found in nectar from food resources to help produce these spermatophores, which are then passed to the female when reproducing. The spermatophore increases female fitness and aids female performance in reproduction, and its nutrients are also assimilated later into the eggs that are laid, leading to heavier larvae.[29]

Thermoregulation

Small heath butterflies typically live well in dry, open landscapes with higher temperatures, in comparison to other species of satyrine butterflies. When temperatures are significantly high, lifespan is shortened but the small heath will fare better than shade-dwelling species, such as the speckled wood, Pararge aegeria. Like other butterflies, it has a small range of optimum temperatures and can regulate its temperatures in a small variety of ways, such as positioning its body to maximally absorb sunlight. In high temperature habitats, the small heath produces eggs at a relatively high rate, has good fecundity, and survives well as compared to woodland butterflies.[30] Male butterflies will also tend to drift and be vagrant in their search for females rather than perch in their territories and wait, as they would do in optimum or sub-optimum temperatures.[22]

Threats

Parasitism

The Trogus lapidator (parasitic wasp) and other varieties of Ichneumoninae species will often parasitize Lepidoptera pupae as parasitoids. The parasite eventually emerges from the host pupae as an adult by slicing out a cap at the terminal end of the chrysalis and breaking through. In small heath pupae, staining can sometimes be seen around the cut site of the cap.[31]

Interactions with humans

As a grassland species, the effects of intense, widespread agriculture is a concern for the welfare of the small heath. Grassland management through periodic ecological disturbances (i.e. mowing) is considered necessary to maintain “semi-natural” grasslands. Negative effects of mowing include the loss of biodiversity, the conversion of natural grasslands into agricultural fields, mortality, and loss of nectar resources. However, a study shows that such disturbances of these habitats may actually lead to an increase in the population of grassland butterflies including the small heath.[23]

Conservation

Overall, the small heath is generally common and abundant throughout its geographic distribution, particularly in Europe.[14] Urban habitats have become a significant focus in the conservation of the small heath due to the widespread green fragments forming chains of ecological biodiversity.[24] In a study of elevated atmospheric CO2 levels on development, it was determined that larval development time increased due to elevated CO2 levels, suggesting an effect of CO2 on larval performance. Additionally, it was found that food-plant preferences of larvae might also be affected, which could play a future evolutionary role, although this is an area that requires further research.[9]

Status in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the distribution of the Coenonympha tullia is significantly reduced as a result of climate change. Also satyrine species of the genus Coenonympha, the C. hero and C. arcania have gone extinct. One study shows that the small heath has adapted well to climate change and will continue to survive because it can adapt biologically to altered environments. In response to these environmental changes (i.e. temperature), the small heath can overwinter in diapause, which promotes its survival through rapid development.[32]

Status in England

The small heath, like its cousin the wall brown, has been in serious decline across much of southern England for reasons unclear, and was accordingly designated as a UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Species (research only) by DEFRA in 2007.[3] These butterflies typically live in colonies, which have been negatively impacted by construction, human development, and general habitat loss in recent years. In 2007, the IUCN category status listed the small heath as near threatened.[4]

References

- van Swaay, C., Wynhoff, I., Verovnik, R., Wiemers, M., López Munguira, M., Maes, D., Sasic, M., Verstrael, T., Warren, M. & Settele, J. (2010). "Coenonympha pamphilus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T174461A7076327. Retrieved 13 December 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Coenonympha pamphilus Linnaeus, 1758". Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "UK Butterflies - Small Heath - Coenonympha pamphilus". www.ukbutterflies.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- "British Butterflies - A Photographic Guide by Steven Cheshire". www.britishbutterflies.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- Wickman, Per-Clof. “The Influence of Temperature on the Territorial and Mate Locating Behaviour of the Small Heath Butterfly, Coenonympha Pamphilus (L.) (Lepidoptera: Satyridae).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, vol. 16, no. 3, 1985, pp. 233–238., doi:10.1007/bf00310985.

- Org, Registry-Migration.Gbif (2017). "GBIF Backbone Taxonomy". GBIF Secretariat. doi:10.15468/39omei. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sei, M. (2004). "Larval Adaptation of the Endangered Maritime Ringlet Coenonympha tullia nipisiquit Mc Donnough (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) to a Saline Wetland Habitat". Environmental Entomology. 33 (6): 1535–1540. doi:10.1603/0046-225X-33.6.1535. S2CID 85755768.

- Brau, Markus; Dolek, Matthias; Stettmer, Christian (2010). "Habitat requirements, larval development and food preferences of the German population of the False Ringlet Coenonympha oedippus (FABRICIUS, 1787) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) - Research on the ecological needs to develop management tools" (PDF). Oedippus. 26: 41–51.

- Goverde, Marcel; Erhardt, Andreas (2003-01-01). "Effects of elevated CO2 on development and larval food-plant preference in the butterfly Coenonympha pamphilus (Lepidoptera, Satyridae)". Global Change Biology. 9 (1): 74–83. Bibcode:2003GCBio...9...74G. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00520.x.

- Cahenzli, Fabian; Erhardt, Andreas (2012-09-01). "Nectar sugars enhance fitness in male Coenonympha pamphilus butterflies by increasing longevity or realized reproduction". Oikos. 121 (9): 1417–1423. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20190.x.

- Wickman, Per-Olof (1992). "Mating systems of Coenonympha butterflies in relation to longevity". Animal Behaviour. 44: 141–148. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80763-8. S2CID 53195723.

- "Coenonympha". ftp.funet.fi. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- Linné, Carl von; Lange, Johann Joachim; Linné, Carl von (1760). Caroli Linnaei ... Systema naturae: per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. LuEsther T. Mertz Library New York Botanical Garden. Halae Magdeburgicae : Typis et sumtibus Io. Iac. Curt.

- South, Richard (1906). The butterflies of the British Isles. London: F. Warne. pp. 136–138.

- Seitz. A. in Seitz, A. ed. Band 1: Abt. 1, Die Großschmetterlinge des palaearktischen Faunengebietes, Die palaearktischen Tagfalter, 1909, 379 Seiten, mit 89 kolorierten Tafeln (3470 Figuren)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Coenonympha Hübner, [1819]" at Markku Savela's Lepidoptera and Some Other Life Forms

- Brakefield, P.M.; Emmet, A. M. (1990), Emmet, A. M.; Heath, J. (eds.), "Coenonympha pamphilus (Linnaeus). Pages", The Moths and Butterflies of Great Britain and Ireland, 7 (1 (Hesperiidae to Nymphalidae)): 277–279

- Dennis, R. L. H. (20 March 1989). "Butterfly wing morphology variation in the British Isles: the influence of climate, behavioural posture and the hostplant-habitat". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 38 (4): 323–348. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1989.tb01581.x.

- Tuzov, V.K. (2000). Guide to the butterflies of Russia and adjacent territories (Lepidoptera, Rhopalocera). Vol. 2. Libytheidae, Danaidae, Nymphalidae, Riodinidae, Lycaenidae. Sofia: Pensoft. ISBN 978-9546420954. OCLC 45109002.

- Wallisdevries, Michiel F.; Poschlod, Peter; Willems, Jo H. (2002). "Challenges for the conservation of calcareous grasslands in northwestern Europe: Integrating the requirements of flora and fauna". Biological Conservation. 104 (3): 265–273. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00191-4.

- Garcia-Barros, Enrique (January 2006). "Number of larval instars and sex-specific plasticity in the development of the small heath butterfly, Coenonympha pamphilus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)". European Journal of Entomology. 103: 47–53. doi:10.14411/eje.2006.007.

- Wickman, Per-Olof (1985). "TErritorial defence and mating success in males of the small heath butterfly, coenonympha pamphilus L. (Lepidoptera: Satyridae)". Animal Behaviour. 33 (4): 1162–1168. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80176-7. S2CID 53165861.

- Lebeau, Julie; Wesselingh, Renate A.; Dyck, Hans Van (2015-08-18). "Butterfly Density and Behaviour in Uncut Hay Meadow Strips: Behavioural Ecological Consequences of an Agri-Environmental Scheme". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0134945. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1034945L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134945. PMC 4540417. PMID 26284618.

- Angold, P. G.; Sadler, J. P.; Hill, M. O.; Pullin, A.; Rushton, S.; Austin, K.; Small, E.; Wood, B.; Wadsworth, R.; Sanderson, R.; Thompson, K. (2006). "Biodiversity in urban habitat patches". Science of the Total Environment. 360 (1–3): 196–204. Bibcode:2006ScTEn.360..196A. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.08.035. PMID 16297440.

- Besold, Joachim; Huck, Stefan; Schmitt, Thomas (2008). "Allozyme Polymorphisms in the Small Heath,Coenonympha pamphilus: Recent Ecological Selection or Old Biogeographical Signal?". Annales Zoologici Fennici. 45 (3): 217–228. doi:10.5735/086.045.0307. S2CID 54675292.

- Wickman, Per-Olof; Karlsson, Bengt (1987). "Changes in egg colour, egg weight and oviposition rate with the number of eggs laid by wild females of the small heath butterfly, Coenonympha pamphilus". Ecological Entomology. 12 (1): 109–114. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1987.tb00989.x. S2CID 85045063.

- Wiklund, Christer (1984). "Egg-Laying Patterns in Butterflies in Relation to Their Phenology and the Visual Apparency and Abundance of Their Host Plants". Oecologia. 63 (1): 23–29. Bibcode:1984Oecol..63...23W. doi:10.1007/bf00379780. JSTOR 4217346. PMID 28311161. S2CID 29210301.

- Wickman, Per-Olof; Jansson, Peter (1997). "An estimate of female mate searching costs in the lekking butterfly Coenonympha pamphilus". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 40 (5): 321–328. doi:10.1007/s002650050348. S2CID 25290065.

- Cahenzli, Fabian; Erhardt, Andreas (January 2013). "Nectar amino acids enhance reproduction in male butterflies" (PDF). Oecologia. 171 (1): 197–205. Bibcode:2013Oecol.171..197C. doi:10.1007/s00442-012-2395-8. PMID 22744741. S2CID 14761851.

- Karlsson, Bengt; Wiklund, Christer (2005-01-01). "Butterfly life history and temperature adaptations; dry open habitats select for increased fecundity and longevity". Journal of Animal Ecology. 74 (1): 99–104. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2004.00902.x.

- Shaw, Mark; Kan, Pieter; Limburg Stirum, Brigitte Kan-van (2015). "Emergence behaviour of adult Trogus lapidator (Fabricius) (Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, Ichneumoninae, Heresiarchini) from pupa of its host Papilio machaon L. (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae), with a comparative overview of emergence of Ichneumonidae from Lepidoptera pupae in Europe". Journal of Hymenoptera Research. 47: 65–85. doi:10.3897/JHR.47.6508.

- Bink, F.A. (2010). "Coenonympha species in The Netherlands (Lepidoptera)". Entomologische Berichten. 70: 37–44.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Coenonympha pamphilus. |

- Butterfly Conservation species page

- Images of small heath

- Small heath, Moths and Butterflies of Europe and North Africa