Slavic Native Faith's theology and cosmology

Slavic Native Faith (Rodnovery) has a theology that is generally monistic, consisting in the vision of an absolute, supreme God (Rod) who begets the universe and lives as the universe (pantheism and panentheism), present in all its phenomena. Polytheism, that is the worship of the gods or spirits, and ancestors, the facets of the supreme Rod generating all phenomena, is an integral part of Rodnovers' beliefs and practices.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavic Native Faith |

|---|

|

The swastika-like kolovrat is the symbol of Rodnovery.[1] According to the studies of Boris Rybakov, whirl and wheel symbols, which also include patterns like the "six-petaled rose inside a circle" (e.g. ![]() ) and the "thunder mark" (gromovoi znak), represent the supreme Rod and its various manifestations (whether Triglav, Svetovid, Perun or other gods).[2] The vision of Rodnover theology has been variously defined as manifestationism, genotheism, and rodotheism.

) and the "thunder mark" (gromovoi znak), represent the supreme Rod and its various manifestations (whether Triglav, Svetovid, Perun or other gods).[2] The vision of Rodnover theology has been variously defined as manifestationism, genotheism, and rodotheism.

Theological stances

Monism and polytheism: Rod and deities

Prior to their Christianisation, the Slavic peoples were polytheists, worshipping multiple deities who were regarded as the emanations of a supreme God. According to Helmold's Chronica Slavorum (compiled 1168–1169), "obeying the duties assigned to them, [the deities] have sprung from his [the supreme God's] blood and enjoy distinction in proportion to their nearness to the god of the gods".[3] Belief in these deities varied according to location and through time, and it was common for the Slavs to adopt deities from neighbouring cultures.[4] Both in Russia and in Ukraine, modern Rodnovers are divided among those who are monotheists and those who are polytheists;[5] in other words, some emphasise a unitary principle of divinity, while others put emphasis on the distinct gods and goddesses.[6] Some Rodnovers even describe themselves as atheists,[7] believing that gods are not real entities but rather symbolic and/or archetypal.[8]

Monotheism and polytheism are not regarded as mutually exclusive. The shared underpinning is a pantheistic view that is holistic in its understanding of the universe.[7] Similarly to the ancient Slavic religion, a common theological stance among Rodnovers is that of monism, by which the many different gods (polytheism) are seen as manifestations of the single, universal God—generally identified by the concept of Rod,[9] also known as Sud ("Judge") and Prabog ("Pre-God", "First God") among South Slavs.[10] The Rodnover movement of Peterburgian Vedism calls this concept Vsebog (Всебог, "All-God").[11]

In the Russian and Ukrainian centres of Rodnover theology, the concept of Rod has been emphasised as particularly important.[12][13] The root *rod is attested in sources about pre-Christian religion referring to divinity and ancestrality.[12][14] Mathieu-Colas defines Rod as the "primordial God", but the term also literally means the generative power of the family and "kin", "birth", "origin" and "fate" as well.[10] Its negative form, urod, means something wrenched, deformed, degenerated, monstrous.[9] Sometimes, the meaning of the word is left deliberately obscure among Rodnovers, allowing for a variety of different interpretations.[12] The Russian volkhvs Veleslav (Ilya Cherkasov) and Dobroslav (Aleksei Dobrovolsky) explain Rod as a life force that comes in nature and is "all-pervasive" or "omnipresent".[9]

Manifestationism

Cosmologically speaking, Rod is conceived as the spring of universal emanation, which articulates in a cosmic hierarchy of gods.[17] When emphasising this monism, Rodnovers may define themselves as rodnianin, "believers in God"[18] (or "in nativity", "in genuinity"). Already the pioneering Ukrainian leader Volodymyr Shaian argued that God manifests as a variety of different deities.[19]

This theological explanation is called "manifestationism" by some contemporary Rodnovers, and implies the idea of a spirit–matter continuum; the different gods, who proceed from the supreme God, generate differing categories of things not as their external creations (as objects), but embodying themselves as these entities. In their view, beings are the progeny of gods; even phenomena such as the thunder are conceived in this way as embodiments of these gods (in this case, Perun).[20] In the wake of this theology, it is common among Slavic Native Faith practitioners to say that "we are not God's slaves, but God's sons".[12] Some Rodnover groups espouse the idea that specific Slavic populations are the sons of peculiar facets of God; for instance, groups who rely upon the tenth-century manuscript The Lay of Igor's Host may affirm the idea that Russians are the grandchildren of Dazhbog (the "Giving God", "Day God").[12]

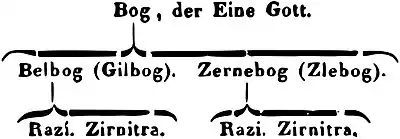

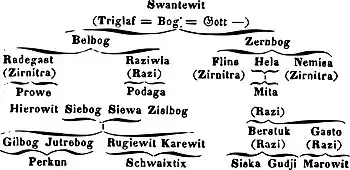

A Russian Rodnover leader, Nikolai Speransky (volkhv Velimir), emphasises a dualistic eternal struggle between forces of good and evil; the former represented by Belobog ("White God"), who created the human soul, and the latter by Chernobog ("Black God"), who created the human body.[21] They are the twofold dynamism through which the supreme God expresses its spirits, taking part in the characteristics of both categories.[22]

Clusters of deities

Pantheons of deities are not unified among practitioners of Slavic Native Faith.[24] Different Rodnover groups often have a preference for a particular deity over others.[6] The Union of Russian Rodnover Communities founded and led by Vadim Kazakov recognises a pantheon of over thirty deities emanated by the supreme Rod;[25] these include attested deities from Slavic pre-Christian and folk traditions, Slavicised Hindu deities (such as Vyshen, i.e. Vishnu, and Intra, i.e. Indra), Iranian deities (such as Simargl and Khors), deities from the Book of Veles (such as Pchelich), and figures from Slavic folk tales such as the wizard Koschei.[26] Rodnovers also believe and worship tutelary deities of specific elements, lands and environments,[27] such as waters, forests and the household. Gods may be subject to functional changes among modern Rodnovers; for instance, the traditional god of livestock and poetry Veles is called upon as the god of literature and communication.[20]

Sylenko's monotheism

In Ukraine, there has been a debate as to whether the religion should be monotheistic or polytheistic.[28] In keeping with the pre-Christian belief systems of the region, the groups who inherit Volodymyr Shaian's tradition, among others, espouse polytheism.[28] Conversely, Lev Sylenko's Native Ukrainian National Faith (RUNVira for short, called "Sylenkoism" in some academic scholarship) regards itself as monotheistic and focuses its worship upon a single God whom they identify by the name Dazhbog.[29] For members of this group, Dazhbog is regarded as the life-giving energy of the cosmos.[30]

Sylenko characterised Dazhbog as "light, endlessness, gravitation, eternity, movement, action, the energy of unconscious and conscious Being".[30] Based on this description, Ivakhiv argued that Sylenkoite theology might better be regarded as pantheistic or panentheistic rather than monotheistic.[30] Sylenko acknowledged that the ancient Ukrainian-Rus were polytheists but believed that a monotheistic view reflected an evolution in human spiritual development and thus should be adopted.[31] A similar view is adopted by the Russian Rodnover denomination of Ynglism.[20] Lesiv recorded one RUNVira member who related that "we cannot believe in various forest, field and water spirits today. Yes, our ancestors believed in these things but we should not any longer".[32] For RUNVira members, polytheism is regarded as backward.[32] Some polytheist Rodnovers have regarded the approach adopted by Sylenko's followers as an inauthentic approach to the religion.[33]

Cosmology

.png.webp)

Dual dynamism: Belobog and Chernobog

According to the Book of Veles, and to the doctrine accepted by many Rodnover organisations, the supreme Rod begets Prav (literally "Right" or "Order"; cf. Greek Orthotes, Sanskrit Ṛta) in primordial undeterminacy (chaos), giving rise to the circular pattern of Svarog ("Heaven", "Sky"; cf. Sanskrit Svarga), which constantly multiplies generating new worlds (world-eggs). Prav works by means of a dual dynamism, represented by Belobog ("White God"[10]) and Chernobog ("Black God"[10]); they are two aspects of the same, appearing in reality as the forces of waxing and waning, giving rise to polarities like up and down, light and dark, male and female, singular and plural. Man and woman are further symbolised by father Svarog itself and mother Lada.[17]

This supreme polarity is also represented by the relation between Rod and Rozanica, literally the "Generatrix", the mother goddess who expresses herself as the three goddesses who interweave destiny (Rozanicy, also known as Sudenicy among South Slavs, where Rod is also known as Sud, "Judge").[10] She is also known as Raziwia, Rodiwa or simply Dewa ("Goddess"), regarded as the singular goddess of whom all lesser goddesses are manifestations.[35] In kinships, while Rod represents the forefathers from the male side, Rozanica represents the ancestresses from the female side. Through the history of the Slavs, the latter gradually became more prominent than the former, because of the importance of the mother to the newborn child.[36]

Triglav

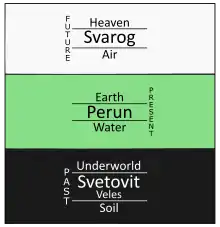

In duality, the supreme Rod's luminous aspect (Belobog) manifests ultimately as threefold, Triglav ("Three-Headed One"[10]). The first of the three persons is the aforementioned Svarog ("Heaven"), and the other two are Svarog's further expressions as Perun ("Thunder") and Svetovid (the "Worldseer", itself four-faced). They correspond to the three dimensions of the cosmos, and to the three qualities of soul, flesh and power. Svarog represents Prav itself and soul, Perun represents Yav and flesh, and Svetovit represents Nav and spiritual power.[37]

According to Shnirelman, this triune vision and associations were codified by Yuri P. Mirolyubov and further elaborated by Valery Yemelyanov, both interpreters of the Book of Veles.[37] In olden times, already Ebbo documented that the Triglav was seen as embodying the connection and mediation between Heaven, Earth and the underworld.[38] Adam of Bremen described the Triglav of Wolin as Neptunus triplicis naturae (that is to say "Neptune of the three natures/generations") attesting the colours that were associated to the three worlds, then further studied by Karel Jaromír Erben: white for Heaven, green for Earth and black for the underworld.[39] Other names of the two manifestations of Svarog are Dazhbog ("Giving God", "Day God") and Svarozhich (the god of fire, literally meaning "Son of Heaven").[10] According to the studies of Jiří Dynda, the three faces of Triglav are rather Perun in the heavenly plane (instead of Svarog), Svetovid in the centre from which the horizontal four directions unfold, and Veles in the underworld.[40] The netherworld, especially in its dark aspect, is indeed traditionally embodied by Veles, who in this function is the god of waters but also the one who guides athwart them in the function of psychopomp (cf. Sanskrit Varuna).[41]

In his study of Slavic cosmology, Dynda compares this axis mundi concept to similar ones found in other Indo-European cultures. He gives weight to the Triglav as a representation of what Georges Dumézil studied as the "Indo-European trifunctional hypothesis" (holy, martial and economic functions reflected by three human types and social classes).[39] The Triglav also represents the interweaving of the three dimensions of time, metaphorically represented as a three-threaded rope.[42] By Ebbo's words, the Triglav is summus deus, the god representing the "sum" of the three dimensions of reality as a mountain or tree (themselves symbols of the axis mundi).[43] In a more abstract theoretical formulation, Dynda says that the three (Triglav) completes the two by springing out as the middle term between the twosome (Belobog and Chernobog), and in turn the threesome implicates the four (Svetovid) as its own middle term of potentiality.[44]

Svetovid

Svetovid ("Worldseer", or more accurately "Lord of Power" or "Lord of Holiness", the root *svet defining the "miraculous and beneficial power", or holy power)[45] is the four-faced god of war and light, and "the most complete reflection of the Slavic cosmological conception", the union of the four horizontal directions of space with the three vertical tiers of the cosmos (Heaven, Earth and the underworld), and with the three times.[44] Helmold defined Svetovid as deus deorum ("god of all gods");[46] Dynda further defines Svetovid, by Jungian words, as a "fourfold (quaternitas) potentiality which comes true in threefoldness (triplicitas)".[44] His four faces are the masculine Svarog ("Heaven", associated to the north direction and the colour white) and Perun ("Thunder", the west and red), and the feminine Mokosh ("Wetness", the east and green) and Lada ("Beauty", the south and black). The four directions and colours also represent the four Slavic lands of original sacred topography.[note 2] They also represent the spinning of the four seasons.[47]

Ultimately, Svetovid embodies in unity the supreme duality (Belobog and Chernobog) through which Rod manifests itself as Prav, and the axial interconnection of the three times with the four dimensions of present space. In other words, he represents Prav spiritualising Yav as Nav; or Svarog manifesting as spirit (Perun) in the material world governed by Veles. Dynda says that this conception reflects a common Indo-European spiritual vision of the cosmos, the same which was also elaborated in early and medieval Christianity as God who is at the same time creator (father), creature (son) and creating activity (spirit).[48]

Prav, Yav and Nav—Heaven, Earth and humanity

_--_Maxim_Sukharev.jpg.webp)

Cosmology of the Book of Veles

According to the Book of Veles, reality has three dimensions, namely the aforementioned Prav, Yav and Nav.[49] Prav ("Right") itself is the level of the gods, who generate entities according to the supreme order of Rod; gods and the entities that they beget "make up" the great Rod. Yav ("actuality") is the level of matter and appearance, the here and now in which things appear in light, coalesce, but also dissolve in contingency; Nav ("probability") is the thin world of human ancestors, of spirit, consisting in the memory of the past and the projection of the future, that is to say the continuity of time.[17] Prav, the universal cosmic order otherwise described as the "Law of Heaven", permeates and regulates the other two hypostases.[50][51]

Genotheism and the worship of ancestors

In her theological commentaries to the Book of Veles, the Ukrainian Rodnover leader Halyna Lozko emphasises the cosmological unity of the three planes of Heaven, Earth and humanity between them. She gives a definition of Rodnover theology and cosmology as "genotheism". God, hierarchically manifesting as different hypostases, a multiplicity of gods emerging from the all-pervading force Svarog, is genetically (rodovid) linked to humanity. On the human plane God is incarnated by the progenitors/ancestors and the kin lineage, in the Earth. Ethics and morality ultimately stem from this cosmology, as harmony with nature is possible only in the relationship between an ethnic group and its own land.[52] The same vision of a genetic essence of divinity is called "rodotheism" by the Ynglists.[53]

This is also the meaning of the worship of human progenitors, whether the Slavs' general forefather Or or Oryi,[54] or local forefathers such as Dingling worshipped by Vladivostok Rodnovers.[55] Divine ancestors are the spirits who generate and hold together kins, they are the kins themselves. The Russian volkhv Dobroslav emphasises the importance of blood heritage, since, according to him, the violation of kinship purity brings about the loss of the relationship with the kin's divine ancestor.[56] The Ukrainian Rodnover and scholar Yuri Shylov has developed a theory of God as a spiral "information field" that expresses itself in self-conscious humanity, which comes to full manifestation in the Indo-European "Saviour" archetype.[52]

See also

Notes

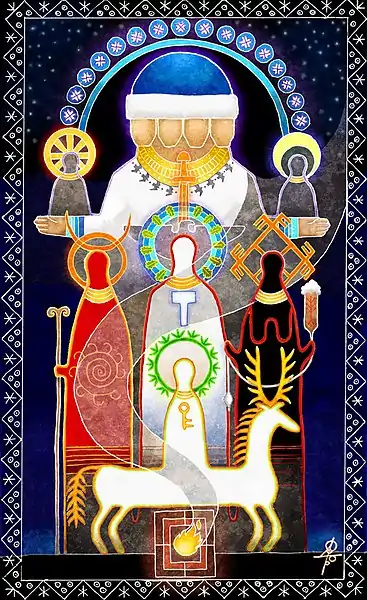

- The Seven Gods, by Russian Rodnover artist Maxim Sukharev, represents the seven major deities of Slavic theo-cosmology, together constituting the hierarchy emanating from the supreme God (Rod). The elements of the drawing are the following ones:

- The central axis is Svarog ("Heaven"), comprising his three forms: the four-faced Svetovid ("Worldseer"), Perun ("Thunder") at the very centre, and Svarozhich ("Son of Heaven") below. Further below Svarozhich there is another form of he himself contained in a squared receptacle, Ognebog ("Fire God").

- On the right and left hand of Svetovid there are, respectively, Belobog ("White God") and Chernobog ("Black God"), themselves in the guise of Dazhbog ("Day God") and Jutrobog ("Moon God"). They are the supreme polarity upon which all the alternating ways of divine manifestation rely.

- To the left and to the right of the white figure of Perun, there are, respectively, the black figure of the great goddess Mokosh/Mat Syra Zemlya ("Wetness/Damp Mother Earth") and the red figure of Veles (the male god belonging to the Earth and god of tamed animals).

- The three forms of Svarog and the three gods Perun, Veles and Mokosh constitute intersecting trinities (Triglav, Tribog), which correspond to the three dimensions: Prav, Yav and Nav. Prav, literally "Right", is ultimately the central axis of Heaven itself, functioning as the medium of all dimensions of space-time. In the guise of thunder (Perun) it impregnates matter (Mokosh), which retains its rhythmic squaring regulations (thus constituting Nav, which is the continuity of time); in the guise of the Son of Heaven it comes to light in present reality (Yav), and is fostered by humanity (Veles), and preserved as the hearth (Ognebog).

- The four faces of Svetovid, the four colours and four directions, also correspond to the four Russias of folk cosmology: White Ruthenia, Red Ruthenia, the Black Sea regions and Green Ukraine. See: Svetovid in the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedic Dictionary, 1987.

References

Citations

- Pilkington & Popov 2009, p. 282.

- Ivanits 1989, pp. 14, 17.

- Rudy 1985, p. 5.

- Shnirelman 2017, p. 89.

- Lesiv 2013a, p. 90; Aitamurto 2016, p. 65; Shnirelman 2017, p. 90.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 290.

- Shnirelman 2017, p. 102.

- Shizhenskii & Aitamurto 2017, p. 109.

- Aitamurto 2016, p. 65.

- Mathieu-Colas 2017.

- Popov 2016, Славянская народная религия (Родноверие) / Slavic indigenous religion (Native Faith).

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 188.

- Lesiv 2017, p. 142.

- Pilkington & Popov 2009, p. 288.

- Creuzer & Mone 1822, p. 197.

- Creuzer & Mone 1822, pp. 195–197; Heck 1852, pp. 289–290.

- Rabotkina 2013, p. 240.

- Pilkington & Popov 2009, p. 269.

- Lesiv 2013b, p. 130.

- Aitamurto 2016, p. 66.

- Shnirelman 2017, p. 93.

- Heck 1852, pp. 289–290.

- Hanuš 1842, p. 182.

- Laruelle 2008, pp. 289–290.

- Belov, Maxim; Garanov, Yuri (10 February 2015). "Adversus Paganos". astrsobor.ru. Journal of the Ascension Cathedral of Astrakhan. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- Shnirelman 2017, p. 95.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 204.

- Lesiv 2013a, p. 90.

- Ivakhiv 2005c, p. 225; Lesiv 2013a, p. 90; Lesiv 2013b, p. 130.

- Ivakhiv 2005c, p. 225.

- Lesiv 2013a, p. 91.

- Lesiv 2013a, p. 92.

- Ivakhiv 2005c, p. 223.

- Shkandrij, Miroslav. "Reinterpreting Malevich: Biography, Autobiography, Art". Canadian-American Slavic Studies. 36 (4). pp. 405–420. (see p. 415).

- Hanuš 1842, pp. 135, 281.

- Máchal 1918, p. 249.

- Shnirelman 1998, p. 8, note 35.

- Dynda 2014, p. 60.

- Dynda 2014, p. 63.

- Dynda 2014, pp. 74–75.

- Dynda 2014, p. 72.

- Dynda 2014, p. 74.

- Dynda 2014, p. 64.

- Dynda 2014, p. 75.

- Mathieu-Colas 2017; Rudy 1985, p. 18.

- Dynda 2014, p. 59, note 9.

- Leeming 2005, p. 369: Svantovit.

- Dynda 2014, p. 76.

- Shnirelman 2017, p. 101.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 202; Ivakhiv 2005c, p. 230.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 290; Aitamurto 2016, pp. 66–67.

- Ivakhiv 2005a, p. 23.

- "Rodotheism – the veneration of the Kin (Родотеизм – это почитание Рода)". Derzhava Rus. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017.

- Ivakhiv 2005a, p. 14, cites Or.

- Shnirelman 2007, p. 54, cites Oryi and Dingling.

- Shnirelman 2007, p. 54–55.

Sources

- Aitamurto, Kaarina (2006). "Russian Paganism and the Issue of Nationalism: A Case Study of the Circle of Pagan Tradition". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 8 (2): 184–210.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2016). Paganism, Traditionalism, Nationalism: Narratives of Russian Rodnoverie. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781472460271.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creuzer, Georg Friedrich; Mone, Franz Joseph (1822). Geschichte des Heidentums im nördlichen Europa. Symbolik und Mythologie der alten Völker (in German). 1. Georg Olms Verlag. ISBN 9783487402741.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dynda, Jiří (2014). "The Three-Headed One at the Crossroad: A Comparative Study of the Slavic God Triglav" (PDF). Studia mythologica Slavica. Institute of Slovenian Ethnology. 17: 57–82. ISSN 1408-6271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanuš, Ignác Jan (1842). Die Wissenschaft des Slawischen Mythus im weitesten, den altpreussisch-lithauischen Mythus mitumfassenden Sinne. Nach Quellen bearbeitet, sammt der Literatur der slawisch-preussisch-lithauischen Archäologie und Mythologie (in German). J. Millikowski.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heck, Johann Georg (1852). "The Slavono-Vendic Mythology". Iconographic Encyclopaedia of Science, Literature, and Art. 4. New York: R. Garrigue. pp. 289–293.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivakhiv, Adrian (2005a). "In Search of Deeper Identities: Neopaganism and "Native Faith" in Contemporary Ukraine". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 8 (3): 7–38. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2005.8.3.7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2005b). "Nature and Ethnicity in East European Paganism: An Environmental Ethic of the Religious Right?". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 7 (2): 194–225.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2005c). "The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith". In Michael F. Strmiska (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 209–239. ISBN 978-1851096084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765630889.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laruelle, Marlène (2008). "Alternative Identity, Alternative Religion? Neo-Paganism and the Aryan Myth in Contemporary Russia". Nations and Nationalism. 14 (2): 283–301.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leeming, David (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Sydney: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190288884.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lesiv, Mariya (2013a). The Return of Ancestral Gods: Modern Ukrainian Paganism as an Alternative Vision for a Nation. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0773542624.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2013b). "Ukrainian Paganism and Syncretism: 'This Is Indeed Ours!'". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 128–145. ISBN 978-1-844656622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2017). "Blood Brothers or Blood Enemies: Ukrainian Pagans' Beliefs and Responses to the Ukraine-Russia Crisis". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 133–156. ISBN 978-1-137-57040-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Máchal, Jan (1918). "Slavic Mythology". In L. H. Gray (ed.). The Mythology of all Races. III, Celtic and Slavic Mythology. Boston. pp. 217–389.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mathieu-Colas, Michel (2017). "Dieux slaves et baltes" (PDF). Dictionnaire des noms des divinités. France: Archive ouverte des Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société, Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Retrieved 24 May 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pilkington, Hilary; Popov, Anton (2009). "Understanding Neo-paganism in Russia: Religion? Ideology? Philosophy? Fantasy?". In George McKay (ed.). Subcultures and New Religious Movements in Russia and East-Central Europe. Peter Lang. pp. 253–304. ISBN 9783039119219.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Popov, Igor (2016). Справочник всех религиозных течений и объединений в России [The Reference Book on All Religious Branches and Communities in Russia] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rabotkina, S. (2013). "Світоглядні та обрядові особливості сучасного українського неоязичництва" [Worldview and ritual features of modern Ukrainian Neopaganism]. Herald of Dnipropetrovsk University. Philosophy, Sociology, Politology (in Ukrainian). 4 (23): 237–244.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rudy, Stephen (1985). Contributions to Comparative Mythology: Studies in Linguistics and Philology, 1972–1982. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110855463.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shizhenskii, Roman; Aitamurto, Kaarina (2017). "Multiple Nationalisms and Patriotisms among Russian Rodnovers". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 109–132. ISBN 978-1-137-57040-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shnirelman, Victor A. (1998). Russian Neo-pagan Myths and Antisemitism. Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism, Acta no. 13. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, The Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2007). "Ancestral Wisdom and Ethnic Nationalism: A View from Eastern Europe". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 9 (1): 41–61. doi:10.1558/pome.v9i1.41.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2017). "Obsessed with Culture: The Cultural Impetus of Russian Neo-Pagans". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 87–108. ISBN 978-1-137-57040-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)