Skipsea Castle

Skipsea Castle was a Norman motte and bailey castle near the village of Skipsea, East Riding of Yorkshire, England. Built around 1086 by Drogo de la Beuvrière, apparently on the remains of an Iron Age mound, it was designed to secure the newly conquered region, defend against any potential Danish invasion and control the trade route across the region leading to the North Sea. The motte and the bailey were separated by Skipsea Mere, an artificial lake that was linked to the sea during the medieval period via a navigable channel. The village of Skipsea grew up beside the castle church, and the fortified town of Skipsea Brough was built alongside the castle around 1160 to capitalise on the potential trade.

| Skipsea Castle | |

|---|---|

| Skipsea, East Riding of Yorkshire, England | |

The castle's motte | |

Skipsea Castle | |

| Coordinates | 53.978668°N 0.229589°W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Earthworks only remain |

| Site history | |

| Built | c. 1086 |

| Built by | Drogo de la Beuvrière |

| Events | Rebellion of William de Forz |

In 1221 the castle's owner, William de Forz, the Count of Aumale, rebelled against Henry III; the fortification was captured by royalist forces and the King ordered it to be destroyed. The remains of the castle had little value by the end of the 14th century and Skipsea Brough failed to attract many inhabitants. The castle passed into the control of the state in the early 20th century and various archaeological investigations were carried out between 1987 and 2001. In the 21st century, Skipsea Castle is managed by English Heritage and open to visitors.

History

Iron Age

The mound which Skipsea Castle was built upon a much earlier Iron Age structure[1] of comparable construction to Silbury Hill in Wiltshire. Internal examination in 2016, through core sample drilling revealed seeds and other organic matter dating the period of construction to around 400 BC.[2]

11th – 12th centuries

Skipsea Castle was built around 1086 by Drogo de Beavriere, a Flemish mercenary and the first Lord of Holderness, following the Norman conquest of England and the Harrying of the North.[3] The region was on the frontier of Norman power and the lordship was intended to protect central Yorkshire against potential Danish raids across the North Sea.[4] Skipsea formed the administrative centre of Drogo's huge estates, which stretched from the Humber to Bridlington, as well as serving as his caput, or principal residence.[5]

The name "Skipsea" has Scandinavian roots and meant a lake that was navigable by ships.[6] In the medieval period the site was an inland harbour, connected via a navigable channel to the North Sea, which in the 21st century is only around 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) away.[7] The surrounding region was referred to as an "island" during this period, due to the surrounding estuary and flood plains.[8] The site of the castle was strategically important, as it lay on the main trading route through the marshes and was accessible by the sea; the castle had military and economic functions, being designed both to control the newly conquered Norman lands and to manage trade in and out of the inland harbour.[9]

The castle took the form of a motte and bailey design, and a dam was probably constructed to turn the surrounding marshy, low-lying land into an artificial lake, called Skipsea Mere, in turn connected the channel leading to the sea.[10] The complex had its own private harbour, and probably a boat yard and a fresh-water fishery.[11] By the end of the 11th century a church had been built to the east of the castle across the mere, and the village of Skipsea soon grew up alongside the church.[6] Drogo settled 10 knights on lands near the castle in an arrangement known as a castlery or castle-guard system, under which the knights helped to guard the castle in return for their estates, and one of them probably built his own smaller fortification at nearby Aldborough.[12]

After the suspicious death of his wife Drogo fled England, and the castle was reassigned by William the Conqueror to Odo, the Count of Aumale.[11] In 1096 it passed to Arnulf de Montgomery, but returned to the Aumales in 1102, who held it until 1221.[11] Trade initially flourished and as a result William le Gros founded the fortified town of Skipsea Brough along the ridgeway just south of the castle, probably around 1160.[13] The town was intended to bring in valuable revenue to the earls, but would also have helped to defend the castle on its most vulnerable, overlooked side.[14] The castle-guard system lapsed, with the surrounding estates paying their rents in cash instead.[6]

13th – 14th centuries

After around 1200 the castle declined in importance: it was poorly situated, the threat of Danish raids had now passed, and so the nearby manor of Burstwick became the new administrative centre for the lordship instead.[15] In January 1220 William de Forz, the Count of Aumale by marriage, rebelled against Henry III; part of their dispute involved the ownership of the estate of Driffield, 11 miles (18 km) away from Skipsea Castle, which Henry had seized the previous year, but William had been in disagreement with Henry's policies for several years before.[16]

William was promptly excommunicated and Henry moved quickly to suppress the revolt.[17] The barons in the north were ordered to besiege William's castles, including Skipsea, and William shortly surrendered himself to the King and was ultimately pardoned.[18] Following the rebellion, Henry ordered Skipsea Castle to be destroyed, although it is uncertain to what extent this order was actually carried out.[19] William passed on the castle to his own son, another William, but on the death of his son's widow, Isabella, it passed to the Crown in 1293.[20]

Skipsea Mere was drained in the second half of the 14th century and by 1397 the castle was considered worthless: the 20 acres (8.1 ha) of land around it became used for pasturing animals.[21] The counts of Aumale used the manor house at nearby Cleeton when they visited the area.[6] Probably because of its poor location, the town of Skipsea Brough also proved unsuccessful as a commercial site.[22] There were only three burgesses in the town paying rent in 1260, and by the late 14th century the town was largely abandoned; in 1377 there were only 95 people registered for the poll tax in the two settlements of Skipsea and Skipsea Brough combined.[22]

15th – 21st centuries

Further drainage of the mere occurred around 1720 and its land was reclaimed for farming.[11] The ground remained marshy and still occasionally flooded at the start of the 20th century.[23] In 1911 the castle was placed into the guardianship of the Commissioners of Works and Public Buildings, later passing into the control of the government heritage agency English Heritage.[6] Archaeological surveys of the site were carried out in 1987, 1988, 1992 and 2001.[11]

The castle is protected as a Scheduled Monument under UK law and the remaining earthworks generally well preserved, but between 2010 and 2014 English Heritage expressed concerns about its condition and the impact of drainage, and the consequent drying out of the land, on the castle's earthworks.[24] Only a handful of buildings survive in the castle's planned town of Skipsea Brough.[25]

Architecture and landscape

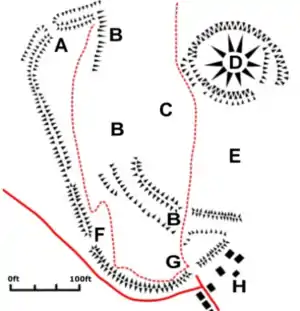

Skipsea Castle was a motte and bailey design, with the two parts of the fortification divided by Skipsea Mere.[11] The mere surrounded the motte; the south-east corner of the mere was cut off by two causeways to the south and east of the motte.[11] Eels were recorded being caught in the lake during the 13th century, and the south-eastern corner may have formed a fresh-water fishery.[26] A curved channel, approximately 25 by 200 metres (82 by 656 ft) in size and ultimately leading to the North Sea, flowed around down the south-west side of the motte, giving boats access to wharves along the inside of the bailey, and concluded in a possible boat yard at the eastern end of the channel.[11] There may have been an additional inland harbour just to the west of the bailey, but archaeologists are divided on this issue.[27]

The motte, constructed from sand and gravel, was deliberately built on a natural glacial mound, making it appear unusually large.[10] It is 100 metres (330 ft) in diameter and 11 metres (36 ft) high, with a 0.25 acres (0.10 ha) of space on the top, protected around the base by a 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) high bank and a ditch up to 10 metres (33 ft) wide, although when first built these would have been taller and deeper than today.[26] There was a timber keep on the motte, and possibly a stone gatehouse at the south-east corner, leading onto the earthwork causeway that crossed the mere south to link the motte with the bailey.[11] The eastern causeway linked the motte with the church in Skipsea village.[11]

The bailey was approximately 300 by 100 metres (980 by 330 ft), covering an area of around 8.25 acres (3.34 ha), curving around the west and south side of the castle.[26] Its earthworks were built from clay, with a rampart up to 4 metres (13 ft) high, protected by a 10-metre (33 ft) wide ditch, originally up to 4 metres (13 ft) deep.[11] The main entrance to the bailey was positioned on the southern side, and was known as Bail Gate and guarded by a gatehouse, with a subsidiary entrance on the north side, linked by a path.[11] A break in the earthworks, now called Scotch Gap, was cut out during the 13th-century destruction of the castle, and the bank has been damaged in other ways from the installation of drainage works.[11]

References

- "Norman Neighbours", Episode 11, Series 12, Time Team, 2005

- "Skipsea Castle was built on Iron Age mound, excavation reveals", The Guardian, 3 October 2016, retrieved 3 October 2016

- "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; Wessex Archaeology 2005, pp. 5–6

- Pounds 1994, p. 40; "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015

- "List Entry", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; Pounds 1994, p. 40

- Allison, K. J.; Baggs, A. P.; Cooper, T.N.; Davidson-Cragoe, C.; Walker, J., Kent, G. H. R. (ed.), "North division: Skipsea", British History Online, retrieved 22 February 2015

- Creighton 2002, p. 42; Allison, K. J.; Baggs, A. P.; Cooper, T.N.; Davidson-Cragoe, C.; Walker, J., Kent, G. H. R. (ed.), "North division: Skipsea", British History Online, retrieved 22 February 2015; "List Entry", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015

- Creighton 2002, p. 104

- "List Entry", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; Dalton 1994, p. 77; "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; Creighton 2002, pp. 104–105

- "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; "List Entry", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015

- "List Entry", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015

- Pounds 1994, p. 40; Dalton 1994, p. 75; Allison, K. J.; Baggs, A. P.; Cooper, T.N.; Davidson-Cragoe, C.; Walker, J., Kent, G. H. R. (ed.), "North division: Skipsea", British History Online, retrieved 22 February 2015

- Allison, K. J.; Baggs, A. P.; Cooper, T.N.; Davidson-Cragoe, C.; Walker, J., Kent, G. H. R. (ed.), "North division: Skipsea", British History Online, retrieved 22 February 2015; "List Entry", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015

- "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015

- "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; Pounds 1994, p. 40

- Carpenter 1990, pp. 229–231

- Carpenter 1990, pp. 229, 233

- Carpenter 1990, pp. 233–234

- Allison, K. J.; Baggs, A. P.; Cooper, T.N.; Davidson-Cragoe, C.; Walker, J., Kent, G. H. R. (ed.), "North division: Skipsea", British History Online, retrieved 22 February 2015; List Entry; Historic England, "Skipsea Castle (80781)", PastScape, retrieved 22 February 2015

- "William de Forz", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29480, retrieved 22 February 2015; "Isabella de Forz", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, 2008, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/47209, retrieved 22 February 2015; Allison, K. J.; Baggs, A. P.; Cooper, T.N.; Davidson-Cragoe, C.; Walker, J., Kent, G. H. R. (ed.), "North division: Skipsea", British History Online, retrieved 22 February 2015

- "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; Allison, K. J.; Baggs, A. P.; Cooper, T.N.; Davidson-Cragoe, C.; Walker, J., Kent, G. H. R. (ed.), "North division: Skipsea", British History Online, retrieved 22 February 2015; Wessex Archaeology 2005, p. 6

- Creighton 2002, p. 172; Allison, K. J.; Baggs, A. P.; Cooper, T.N.; Davidson-Cragoe, C.; Walker, J., Kent, G. H. R. (ed.), "North division: Skipsea", British History Online, retrieved 22 February 2015; List Entry; "History and Research: Skipsea Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015

- Armitage 1912, p. 210

- "Heritage At Risk Register, 2014" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 21, retrieved 22 February 2015; "Heritage At Risk Register, 2010" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 36, retrieved 22 February 2015; Historic England, "Skipsea Castle (80781)", PastScape, retrieved 22 February 2015

- Creighton 2002, pp. 171–172

- "List Entry", English Heritage, retrieved 22 February 2015; Armitage 1912, p. 210

- Historic England, "Skipsea Castle (80781)", PastScape, retrieved 22 February 2015

Bibliography

- Armitage, Ella (1912), The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles, London, UK: John Murray, OCLC 752419931

- Carpenter, D. A. (1990), The Minority of Henry III, Berkeley, US and Los Angeles, US: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07239-8CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creighton, O. H. (2002), Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England, London, UK: Equinox, ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8

- Dalton, Paul (1994), Conquest, Anarchy, and Lordship : Yorkshire, 1066–1154, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521450980CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994), The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wessex Archaeology (2005), Skipsea Grange, Skipsea, Holdenress, East Riding of Yorkshire: A Report on an Archaeological Evaluation and an Assessment of the Results, Salisbury, UK: Wessex Archaeology

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skipsea Castle. |