Sixgill stingray

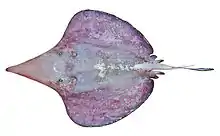

The sixgill stingray (Hexatrygon bickelli) is a species of stingray and the only extant member of the family Hexatrygonidae. Although several species of sixgill stingrays have been described historically, they may represent variations in a single, widespread species. This flabby, heavy-bodied fish, described only in 1980, is unique among rays in having six pairs of gill slits rather than five. Growing up to 1.7 m (5.6 ft) long, it has a rounded pectoral fin disc and a long, triangular, and flexible snout filled with a gelatinous substance. It is brownish above and white below, and lacks dermal denticles.

| Sixgill stingray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Hexatrygon Heemstra & M. M. Smith, 1980 |

| Species: | H. bickelli |

| Binomial name | |

| Hexatrygon bickelli Heemstra & M. M. Smith, 1980 | |

| |

| Range of the sixgill stingray[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Hexatrematobatis longirostris Chu & Meng, 1981 | |

Benthic in nature, the sixgill stingray is usually found over upper continental slopes and seamounts at depths of 500–1,120 m (1,640–3,670 ft). It has been recorded from scattered locations in the Indo-Pacific from South Africa to Hawaii. This species probably uses its snout to probe for food in the bottom sediment. Its jaws are greatly protrusible, allowing it to capture buried prey. The sixgill stingray gives live birth, with litters of two to five pups. The IUCN has assessed this ray as Least Concern, because it faces minimal fishing pressure across most of its range.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The first known sixgill stingray, an intact female 64 cm (25 in) across, was found on a beach near Port Elizabeth, South Africa. It was described as a new species and placed in its own family by Phillip Heemstra and Margaret Smith, in a 1980 article for the Ichthyological Bulletin of the J. L. B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology. The generic name Hexatrygon is derived from the Greek hexa ("six") and trygon ("stingray"), referring to the number of gill slits. The specific name bickelli honors Dave Bickell, a journalist who discovered the original specimen.[3][4]

Following the description of H. bickelli, four additional species of sixgill stingray were described on the basis of morphological differences. However, their validity was brought into question after comparative studies revealed that traits such as snout shape, body proportions, and tooth number vary greatly with age and among individuals. Taxonomists therefore concluded tentatively that there is only a single species of sixgill stingray,[4] though genetic analysis is needed to determine whether this is truly the case.[1] Phylogenetic studies using morphological and genetic data have generally concurred that the sixgill stingray is the most basal member of the stingray lineage.[5][6][7][8] An extinct relative, H. senegasi, lived during the Middle Eocene (49–37 million years ago).[9]

Description

The sixgill stingray has a bulky, flabby body with a rounded pectoral fin disc that is longer than wide. The triangular snout is much longer in adults than in juveniles (making up almost two-fifths of the disc length), and is filled with a clear gelatinous material; because of this, the snout of a dead specimen can shrink significantly when exposed to air or preservatives. The tiny eyes are placed far apart and well ahead of the larger spiracles. Between the widely spaced nostrils are a pair of short and fleshy flaps that are joined in the middle to form a curtain of skin. The mouth is wide and nearly straight. In either jaw are 44–102 rows of small, blunt teeth arranged in a quincunx pattern; the teeth are more numerous in adults. Six pairs of small gill slits occur on the underside of the disc; all other rays have five pairs (a few sharks also have six or more pairs of gill slits, for example in the genus Hexanchus).[2][4][10] One recorded specimen had six gill slits on the left side and seven on the right.[11] Their pelvic fins are rather large and rounded.[10]

The tail is moderately thick and measures about 0.5–0.7 times as long as the disc. One or two serrated stinging spines are present on its dorsal surface, well back from the base. The end of the tail bears a long, low leaf-shaped caudal fin that is nearly symmetrical above and below. The skin is delicate and entirely lacking dermal denticles. The disc is purplish to pinkish brown above, darkening slightly at the fin margins; the skin is easily abraded, leaving white patches. The underside of the disc is white with dark margins on the pectoral and pelvic fins. The snout is translucent, and the tail and caudal fin are almost black. The largest known specimen is a female 1.7 m (5.6 ft) long.[2][4][10]

Distribution and habitat

The sixgill stingray has been recorded at widely scattered locations in the Indo-Pacific. In the Indian Ocean, it has been reported from South Africa off Port Elizabeth and Port Alfred, southwestern India, several islands of Indonesia, and Western Australia from Exmouth Plateau to Shark Bay. In the Pacific Ocean, it has been found from Japan to Taiwan and the Philippines, as well as off Flinders Reef in Queensland, New Caledonia, and Hawaii.[1][11] This bottom-dwelling species typically inhabits upper continental slopes and seamounts at depths of 500–1,120 m (1,640–3,670 ft). However, it occasionally ventures into shallower water, with one ray observed feeding at a depth of 30 m (98 ft) off Japan. It can be found over sandy, muddy, or rocky bottom substrates.[1][10]

Biology and ecology

The long snout of the sixgill stingray is very flexible both vertically and horizontally, suggesting that the ray uses it to probe for food in the bottom sediment.[2] The underside of the snout is covered by well-developed ampullae of Lorenzini arranged in longitudinal rows, which are capable of detecting the minute electric fields produced by other organisms.[4] The mouth can be protruded downward farther than the length of the head, likely allowing the ray to extract buried prey. The jaws are poorly mineralized, suggesting that it does not feed on hard-shelled animals.[12] There is a record of a specimen with a wound from a cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis).[10] Reproduction in the sixgill stingray is viviparous, with documented litter sizes of between two and five pups.[4] Newly born rays measure around 48 cm (19 in) long. Both males and females mature sexually at approximately 1.1 m (3.6 ft) long.[1]

Human interactions

For the most part, little fishing activity occurs at the depths occupied by the sixgill stingray, thus the IUCN has listed it as Least Concern. In the waters around Taiwan, it is caught in small numbers as bycatch in bottom trawls. The catch rate seems to have decreased in recent years, leading to concerns that it may be locally overfished, though quantitative data are lacking.[1]

References

- McCormack, C.; Wang, Y.; Ishihara, H.; Fahmi, Manjaji, M.; Capuli, E.; Orlov, A. (2009). "Hexatrygon bickelli". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Last, P.R.; Stevens, J.D. (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 396–397. ISBN 978-0674034112.

- Heemstra, P.C.; Smith , M.M. (1980). "Hexatrygonidae, a new family of stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Batoidea) from South Africa, with comments on the classification of batoid fishes". Ichthyological Bulletin (J. L. B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology). 43: 1–17. hdl:10962/d1019701.

- Smith, J.L.B.; Smith, M.; Smith, M.M.; Heemstra, P. (2003). Smith's Sea Fishes. Struik. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-1-86872-890-9.

- Nishida, K. (1990). "Phylogeny of the suborder Myliobatoidei". Memoirs of the Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University. 37: 1–108.

- McEachran, J.D.; Dunn, K.A.; Miyake, T. (1996). "Interrelationships within the batoid fishes (Chondrichthyes: Batoidea)". In Stiassney, M.L.J.; Parenti, L.R.; Johnson, G.D. (eds.). Interrelationships of Fishes. Academic Press. pp. 63–84. ISBN 978-0-12-670951-3.

- Aschliman, N.C.; Claeson, K.M.; McEachran, J.D. (2012). "Phylogeny of Batoidea". In Carrier, J.C.; Musick, J.A.; Heithaus, M.R. (eds.). Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives (second ed.). CRC Press. pp. 57–98. ISBN 978-1439839249.

- Naylor, G.J.; Caira, J.N.; Jensen, K.; Rosana, K.A.; Straube, N.; Lakner, C. (2012). "Elasmobranch phylogeny: A mitochondrial estimate based on 595 species". In Carrier, J.C.; Musick, J.A.; Heithaus, M.R. (eds.). The Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives (second ed.). CRC Press. pp. 31–57. ISBN 978-1-4398-3924-9.

- Adnet, S. (2006). "Two new selachian associations (Elasmobranchii, Neoselachii) from the Middle Eocene of Landes (south-west of France). Implication for the knowledge of deep-water selachian communities". Palaeo Ichthyologica. 10: 5–128.

- Compagno, L.J.V.; Last, P.R. (1999). "Hexatrygonidae: Sixgill stingray". In Carpenter, K.E.; Niem, V.H. (eds.). FAO Identification Guide For Fishery Purposes: The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. 3. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 1477–1478. ISBN 978-92-5-104302-8.

- Babu, C.; Ramachandran, S.; Varghese, B.C. (2011). "New record of sixgill sting ray Hexatrygon bickelli Heemstra and Smith, 1980 from south-west coast of India". Indian Journal of Fisheries. 58 (2): 137–139.

- Dean, M.N.; Bizzarro, J.J.; Summers, A.P. (2007). "The evolution of cranial design, diet, and feeding mechanisms in batoid fishes". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1093/icb/icm034. PMID 21672821.