Sigananda kaSokufa

Sigananda kaZokufa (c. 1815–1906) was a Zulu aristocrat whose life spanned the reigns of four Zulu kings in southeastern Africa. In an address by Mangosuthu Buthelezi at Endlamadoda-Nkandla on 15 September 2001 he said that Inkosi Sigananda's grandfather was Inkosi Mvakela, who married a sister of Nandi, King Shaka's mother, and that his father was Inkosi Zokufa. He also said he had a son called Ndabaningi. At this occasion he unveiled a monument to Inkosi Sigananda.

Life and career

Perhaps the most venerable member of the old Zulu order, Sigananda kaZokufa's life and career spanned the reigns of Shaka kaSenzangakhona (c. 1818–1828), Dingane kaSenzangakhona (1828–1840), Mpande kaSenzangakhona (1840–1872) and Cetshwayo kaMpande (1872–1879). His father had been one of Shaka's contemporaries. In fact Shaka had never managed to defeat the amaChube people, of which Zokufa was chief, but the small clan shrewdly allied itself with Shaka's Zulu kingdom. As a boy, Sigananda was a mat-bearer for Shaka, and under Dingane he served in a military regiment known as the uMkhulutshane ibutho. He was present at the murder of the Voortrekker, Piet Retief, and his followers at Dingane's royal homestead of uMgungundlovu (Zulu for Place of the Great-Elephant).

This massacre and its aftermath had a profound effect on early South African race relations as it led to the Battle of Blood River on 16 December 1838 when Dingane was overthrown by the Voortrekkers. After Dingane's overthrow, he was succeeded by his half-brother Mpande. Sigananda remained an important ally of the king but they fell out after the Battle of Ndondakusuka in 1856, when Sigananda sided with the young prince Cetshwayo against his half-brother (and Mpande's favourite son) Mbuyazi.

Battle of Ndondakusuka

This battle had been about who was the rightful heir to Mpande's throne on his death. Although it had always been assumed Cetshwayo was the rightful heir, Mpande had apparently grown wary of his elder son's ambitions and had encouraged his favourite, Mbuyazi, to stake a claim. The result was a tremendous confrontation between the two sides, which resulted in Mbuyazi's defeat and death.[1][2] Mpande grudgingly acknowledged his son's claim, but shortly afterwards Sigananda was forced into exile.

Cetshwayo's ascension

He crossed into the coastal region known as Natal, which bordered Zululand and took refuge with the Zondi clan. However, on Cetshwayo's ascension to the throne in 1872, he remembered Sigananda's loyalty and recalled him back to Zululand, where he was installed as chief of the amaChube people. Sigananda's base was in the rainy Nkandla Forest, and the amaChube were iron-working people. The traditional stronghold was at Manziphambana, between the Thukela and Mhlathuze rivers.

Sigananda survived the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, in which the British invaded Zululand and overthrew the Zulu kingdom. After the war, Zululand was divided into 13 chieftainships and Cetshwayo was exiled to Cape Town. Sigananda became involved in the civil war which broke out as a result of Britain's divide-and-rule tactics. The Zulu essentially split into two camps: the Mandlakazi (led by a powerful former ally of the royal house, Zibhebhu kaMaphitha) and the royalist uSuthu (led by Cetshwayo on his return from exile, his half-brothers, and other elders such as Sigananda).

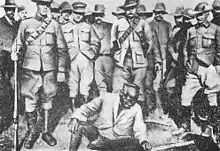

Bambatha Rebellion

When the Mandlakazi beat and scattered the uSuthu, Sigananda came to the rescue of his king by providing refuge for him in the Nkandla forest. Cetshwayo died soon after, and was buried in Sigananda's territory. The old man remained as feisty as ever, though, and in 1906 became embroiled in the Battle of Mome Gorge, after allying himself with the young firebrand Bambatha kaMancinza of the Zondi clan.

His support for Bambatha may have had something to do with the fact that Sigananda had been shielded by Bambatha's grandfather during his exile in Natal all those years ago. But when the rebellion collapsed, Sigananda surrendered to the British. While in captivity he entertained his captors with stories of the great Zulu kings. One soldier was moved to remark that an old man nearing 100, and so obviously adored by his people, had no place in the dank prison to which he had been confined. But, while awaiting his sentence under martial law, Sigananda died of natural causes.