Sialic acid

Sialic acid is a generic term for a family of derivatives of neuraminic acid, an acidic sugar with a nine-carbon backbone.[1] It is also the name for the most common member of this group, N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac or NANA).

Sialic acids are found widely distributed in animal tissues and to a lesser extent in other organisms, ranging from fungi to yeasts and bacteria, mostly in glycoproteins and gangliosides (they occur at the end of sugar chains connected to the surfaces of cells and soluble proteins).[2] That is because it seems to have appeared late in evolution. However, it has been observed in Drosophila embryos and other insects and in the capsular polysaccharides of certain strains of bacteria.[3] Generally, plants do not contain or display sialic acids.[4]

In humans the brain has the highest sialic acid concentration, where these acids play an important role in neural transmission and ganglioside structure in synaptogenesis.[2] More than 50 kinds of sialic acid are known, all of which can be obtained from a molecule of neuraminic acid by substituting its amino group of one of its hydroxyl groups.[1] In general, the amino group bears either an acetyl or a glycolyl group, but other modifications have been described. These modifications along with linkages have shown to be tissue specific and developmentally regulated expressions, so some of them are only found on certain types of glycoconjugates in specific cells.[3] The hydroxyl substituents may vary considerably; acetyl, lactyl, methyl, sulfate, and phosphate groups have been found.[5]

The term "sialic acid" (from the Greek for saliva, σίαλον - síalon) was first introduced by Swedish biochemist Gunnar Blix in 1952.

Structure

The sialic acid family includes 43 derivatives of the nine-carbon sugar neuraminic acid, but these acids rarely appear free in nature. Normally they can be found as components of oligosaccharide chains of mucins, glycoproteins and glycolipids occupying terminal, nonreducing positions of complex carbohydrates on both external and internal membrane areas where they are very exposed and develop important functions.[2]

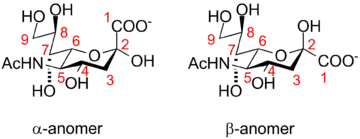

The numbering of the sialic acid structure begins at the carboxylate carbon and continues around the chain. The configuration that places the carboxylate in the axial position is the alpha-anomer.

The alpha-anomer is the form that is found when sialic acid is bound to glycans. However, in solution, it is mainly (over 90%) in the beta-anomeric form. A bacterial enzyme with sialic acid mutarotase activity, NanM, that is able to rapidly equilibrate solutions of sialic acid to the resting equilibrium position of around 90% beta/10% alpha has been discovered.[6]

Biosynthesis

Sialic acid is synthesized by glucosamine 6 phosphate and acetyl-CoA through a transferase, resulting in N-acetylglucosamine-6-P. This becomes N-acetylmannosamine-6-P through epimerization, which reacts with phosphoenolpyruvate producing N-acetylneuraminic-9-P (sialic acid). For it to become active to enter in the oligosaccharide biosynthesis process of the cell, a monophosphate nucleoside is added, which comes from a cytidine triphosphate, turning sialic acid into cytidine monophosphate-sialic acid (CMP-sialic acid). This compound is synthesized in the nucleus of the animal cell.[7][8]

In bacterial systems, sialic acids are biosynthesized by an aldolase enzyme. The enzyme uses a mannose derivative as a substrate, inserting three carbons from pyruvate into the resulting sialic acid structure. These enzymes can be used for chemoenzymatic synthesis of sialic acid derivatives.[9]

Function

Sialic acid-rich glycoproteins (sialoglycoproteins) bind selectin in humans and other organisms. Metastatic cancer cells often express a high density of sialic acid-rich glycoproteins. This overexpression of sialic acid on surfaces creates a negative charge on cell membranes. This creates repulsion between cells (cell opposition)[10] and helps these late-stage cancer cells enter the blood stream. Recent experiments have demonstrated the presence of sialic acid in the cancer-secreted extracellular matrix.[11]

Many bacteria also use sialic acid in their biology, although this is usually limited to bacteria that live in association with higher animals (deuterostomes). Many of these incorporate sialic acid into cell surface features like their lipopolysaccharide and capsule, which helps them evade the innate immune response of the host.[12]

Sialic acid-rich oligosaccharides on the glycoconjugates (glycolipids, glycoproteins, proteoglycans) found on surface membranes help keep water at the surface of cells. The sialic acid-rich regions contribute to creating a negative charge on the cells' surfaces. Since water is a polar molecule with partial positive charges on both hydrogen atoms, it is attracted to cell surfaces and membranes. This also contributes to cellular fluid uptake.

Sialic acid can "hide" mannose antigens on the surface of host cells or bacteria from mannose-binding lectin. This prevents activation of complement.

Sialic acid in the form of polysialic acid is an unusual posttranslational modification that occurs on the neural cell adhesion molecules (NCAMs). In the synapse, the strong negative charge of the polysialic acid prevents NCAM cross-linking of cells.

Administration of estrogen to castrated mice leads to a dose-dependent reduction of the sialic acid content of the vagina. Conversely, the sialic acid content of mouse vagina is a measure of the potency of the estrogen. Reference substances are estradiol for subcutaneous application and ethinylestradiol for oral administration.[13]

Immunity

Sialic acids are found at all cell surfaces of vertebrates and some invertebrates, and also at certain bacteria that interact with vertebrates.

Many viruses such as the Ad26[14] serotype of adenoviruses (Adenoviridae), rotaviruses (Reoviridae) and influenza viruses (Orthomyxoviridae) can use host-sialylated structures for binding to their target host cell. Sialic acids provide a good target for these viruses since they are highly conserved and are abundant in large numbers in virtually all cells. Unsurprisingly, sialic acids also play an important role in several human viral infections. The influenza viruses have hemagglutinin activity (HA) glycoproteins on their surfaces that bind to sialic acids found on the surface of human erythrocytes and on the cell membranes of the upper respiratory tract. This is the basis of hemagglutination when viruses are mixed with blood cells, and entry of the virus into cells of the upper respiratory tract. Widely used anti-influenza drugs (oseltamivir and zanamivir) are sialic acid analogs that interfere with release of newly generated viruses from infected cells by inhibiting the viral enzyme neuraminidase.[15]

Some bacteria also use host-sialylated structures for binding and recognition. For example, evidence indicates that free Sia can behave as a signal to some specific bacteria, like Pneumococcus. Free sialic acid possibly can help the bacterium to recognize that it has reached a vertebrate environment suitable for its colonization. Modifications of Sias, such as the N-glycolyl group at the 5 position or O-acetyl groups on the side chain, may reduce the action of bacterial sialidases. [15]

Metabolism

The synthesis and degradation of sialic acid are distributed in different compartments of the cell. The synthesis starts in the cytosol, where N-acetylmannosamine 6 phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate give rise to sialic acid. Later on, Neu5Ac 9 phosphate is activated in the nucleus by a cytidine monophosphate (CMP) residue through CMP-Neu5Ac synthase. Although the linkage between sialic acid and other compounds tends to be a α binding, this specific one is the only one that is a β linkage. CMP-Neu5Ac is then transported to the endoplasmic reticulum or the Golgi apparatus, where it can be transferred to an oligosaccharide chain, becoming a new glycoconjugate. This bond can be modified by O-acetylation or O-methylation. When the glycoconjugate is mature it is transported to the cell surface.

The sialidase is one of the most important enzymes of the sialic acid catabolism. It can cause the removal of sialic acid residues from the cell surface or serum sialoglycoconjugates. Usually, in higher animals, the glycoconjugates that are prone to be degraded are captured by endocytosis. After the fusion of the late endosome with the lysosome, lysosomal sialidases remove sialic acid residues. The activity of these sialidases is based on the removal of O-acetyl groups. Free sialic acid molecules are transported to the cytosol through the membrane of the lysosome. There, they can be recycled and activated again to form another nascent glycoconjugate molecule in the Golgi apparatus. Sialic acids can also be degraded to acylmannosamine and pyruvate with the cytosolic enzyme acylneuraminate lyase.

Some severe diseases can depend on the presence or absence of some enzymes related to the sialic acid metabolism. Sialidosis would be an example of this type of disorder.[16]

Brain development

Scientists who are investigating the functions of sialic acid are trying to determine whether sialic acid is related to fast brain growth and whether it produces advantages in brain development. It has been demonstrated that human milk contains high levels of sialic acid glycoconjugates. In fact, one study has shown that premature infants, and full-term breast-fed infants at five months of age, had more salivary sialic acid than did formula-fed infants. However human milk varies in sialic acid content, depending upon genetic inheritance, lactation, etc. Investigations are focused on comparing sialic acid’s effects upon breast-fed children versus non-breast-fed children. Brain development is complex but it occurs quickly: by two years of age, a child’s brain reaches about 80% of its adult weight. Children are born with a complete number of brain neurons, but the synaptic connections between them will be elaborated after birth. Sialic acid plays an essential role in proper brain development and cognition, and it is important that the child has an adequate supply at the time when it is needed.

It has been demonstrated that the human brain has more sialic acid than the brains of other mammals (2 – 4 times more). Neural membranes have 20 times more sialic acid than other cellular membranes. It is believed that sialic acid has a decisive role in enabling neurotransmission between neurons. The effects of sialic acid supplementation on learning and memory behaviour has been studied in rodents, as well as in piglets (whose brain structure and function more closely resemble those of humans).

Rat pups supplemented with sialic acid showed improved learning and memory as adults.[17] A diet rich in sialic acid was given to newborn piglets for five weeks. Then learning and memory were evaluated using a visual cue in a maze. A relationship between dietary sialic acid supplementation and cognitive function was seen: the piglets that had been fed high doses of sialic acid learned more quickly and made fewer mistakes. This suggests that sialic acid has an influence upon brain development and learning.[18]

Diseases

Sialic acids are related to some diseases observed in humans.

Salla disease

Salla disease is an extremely rare illness which is considered the mildest form of the free sialic acid accumulation disorders[19] though its childhood form is considered an aggressive variant and people who suffer from it have mental retardation.[20] It is an autosomic recessive disorder caused by a mutation of the chromosome 6.[21] It mainly affects the nervous system [19] and it is caused by a lysosomal storage irregularity which comes from a deficit of a specific sialic acid carrier located on the lysosomal membrane[22] Currently, there is no cure for this disease and the treatment is supportive, focusing on the control of symptoms.[19]

Atherosclerosis

Subfractions of LDL cholesterol that are implicated in causing atherosclerosis have reduced levels of sialic acid.[23] These include small high density LDL particles and electronegative LDL.[23] Reduced levels of sialic acid in small high density LDL particles increases the affinity of those particles for the proteoglycans in arterial walls.[23]

Influenza

All influenza A virus strains need sialic acid to connect with cells. There are different forms of sialic acids which have different affinity with influenza A virus variety. This diversity is an important fact that determines which species can be infected.[24] When a certain influenza A virus is recognized by a sialic acid receptor the cell tends to endocytose the virus so the cell becomes infected.

References

- Varki, Ajit; Roland Schauer (2008). "Sialic Acids". in Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Press. pp. Ch. 14. ISBN 9780879697709.

- Wang, B.; Brand-Miller, J. (2003). "The role and potential of sialic acid in human nutrition". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 57 (11): 1351–1369. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601704. PMID 14576748.

- Mandal, C.; Mandal, C. (1990). "Sialic acid binding lectins". Experientia. 46 (5): 433–441. doi:10.1007/BF01954221. PMID 2189746. S2CID 27075067.

- Varki, Ajit; Roland Schauer (2008). "Sialic Acids". in Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Press. pp. Ch. 14. ISBN 9780879697709.

- Schauer R. (2000). "Achievements and challenges of sialic acid research". Glycoconj. J. 17 (7–9): 485–499. doi:10.1023/A:1011062223612. PMC 7087979. PMID 11421344.

- Severi E, Müller A, Potts JR, Leech A, Williamson D, Wilson KS, Thomas GH (2008). "Sialic acid mutarotation is catalyzed by the Escherichia coli beta-propeller protein YjhT". J Biol Chem. 283 (8): 4841–91. doi:10.1074/jbc.M707822200. PMID 18063573.

- Fulcher CA, "MetaCyc Chimeric Pathway: superpathway of sialic acid and CMP-sialic acid biosynthesis", "MetaCyc, March 2009"

- Warren, Leonard; Felsenfeld, Herbert (1962). "The Biosynthesis of Sialic Acids" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 237 (5): 1421.

- Hai Yu; Harshal Chokhawala; Shengshu Huang & Xi Chen (2006). "One-pot three-enzyme chemoenzymatic approach to the synthesis of sialosides containing natural and non-natural functionalities". Nature Protocols. 1 (5): 2485–2492. doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.401. PMC 2586341. PMID 17406495.

- Fuster, Mark M.; Esko, Jeffrey D. (2005). "The sweet and sour of cancer: Glycans as novel therapeutic targets". Nature Reviews Cancer. 5 (7): 526–42. doi:10.1038/nrc1649. PMID 16069816. S2CID 10330140.

- Dasgupta, Debayan; Pally, Dharma; Saini, Deepak; Bhat, Ramray; Ghosh, Ambarish (2020). "Nanomotors Sense Local Physicochemical Heterogeneities in Tumor Microenvironments". Angewandte Chemie. doi:10.1002/anie.202008681.

- Severi E.; Hood D.W.; Thomas G.H. (2007). "Sialic acid utilization by bacterial pathogens". Microbiology. 153 (9): 2817–2822. doi:10.1099/mic.0.2007/009480-0. PMID 17768226.

- Jürgen Sandow; Ekkehard Scheiffele; Michael Haring; Günter Neef; Klaus Prezewowsky; Ulrich Stache (2007), "Hormones", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–81, doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_089, ISBN 978-3527306732

- "Human adenovirus type 26 uses sialic acid–bearing glycans as a primary cell entry receptor". Science Advances.

- Varki A.; Gagneux P. (2012). "Multifarious roles of sialic acids in immunity". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1253 (1): 16–36. Bibcode:2012NYASA1253...16V. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06517.x. PMC 3357316. PMID 22524423.

- Traving, C.; Schauer, R. (1998). "Structure, function and metabolism of sialic acids". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 54 (12): 1330–1349. doi:10.1007/s000180050258. PMC 7082800. PMID 9893709.

- Oliveros E, Vázquez E, Barranco A, Ramírez M, Gruart A, Delgado-García JM, Buck R, Rueda R, Martín MJ (2018). "Sialic Acid and Sialylated Oligosaccharide Supplementation during Lactation Improves Learning and Memory in Rats". Nutrients. 10 (10): E1519. doi:10.3390/nu10101519. PMC 6212975. PMID 30332832.

- Wang B. (2012). "Molecular Mechanism Underlying Sialic Acid as an Essential Nutrient for Brain Development and Cognition". Adv. Nutr. 3 (3): 465S–472S. doi:10.3945/an.112.001875. PMC 3649484. PMID 22585926.

- "Salla disease | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program".

- "Free sialic acid storage disease". Orphanet. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Ponsot, G. (2007). "Enfermedades por depósito de ácido siálico libre: enfermedad de Salla (incluida su forma infantil grave) y sialuria". EMC - Pediatría (in Spanish). 42: 1–3. doi:10.1016/S1245-1789(07)70257-3.

- "Enfermedades por depósito de ácido siálico libre: Enfermedad de Salla (incluida su forma infantil grave) y sialuria" (in Spanish).

- Ivanova EA, Myasoedova VA, Melnichenko AA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN (2017). "Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein as Biomarker for Atherosclerotic Diseases". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2017 (10): 1273042. doi:10.1155/2017/1273042. PMC 5441126. PMID 28572872.

- Racaniello, Vincent (5 May 2009). "Influenza virus attachment to cells: role of different sialic acids". Virology Blog. Retrieved 10 April 2019.