Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation

Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation (Chinese: 冥王聖幀; lit. 'Sacred Scroll of the King of the Underworld') is a Yuan dynasty silk hanging scroll, measuring 142 × 59 centimetres and dating from the 13th century, with didactic themes: a multi-scenic narrative that depicts Mani's Teachings about the Salvation combines a sermon subscene with the depictions of soteriological teaching in the rest of the painting.[1]

| Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation | |

|---|---|

| Chinese: 冥王聖幀 | |

| |

| Artist | Unknown |

| Year | 13th century |

| Type | Hanging scroll, paint and gold on silk |

| Dimensions | 142.0 cm × 59.2 cm (55.9 in × 23.3 in) |

| Location | Museum of Japanese Art, Nara |

The painting was regarded as a depiction of the six realms of saṃsāra by Japanese Buddhists, therefore it was called "Painting of the Six Paths of Rebirth" (Japanese: 六道図).[2] After being studied by scholars like Takeo Izumi, Yutaka Yoshida, Zsuzsanna Gulácsi and Jorinde Ebert, they concluded that the painting is a Manichaean work of art.[3] It was probably produced by a 13th-century painter from Ningbo, a city in southern China,[4] and is kept today in the Museum of Japanese Art Yamato Bunkakan in Nara, Nara.

Description

The painting is divided into five scenes, with titles given by Zsuzsanna Gulácsi, a Hungarian specialist on Manichaeism.[5]

- The Light Maiden's Visit to Heaven: the first section at the top depicts heaven as a palatial building that forms the focus of a narration of events with the repeated images of a few mythological beings: the Maiden of Light visiting the heaven. It shows on the left the greetings by the host of heaven upon the arrival of Maiden of Light, meeting with the host in the palace in the middle and the Maiden leaving heaven on the right.

- Sermon Around a Statue of Mani: the second scene is the main section and largest among the five, it depicts a sermon performed around the statue of a Manichaean deity (Mani) by two Manichaean elects dressing in white on the right. The elect giving the sermon is seated, while his assistant is standing. On the left seated the layman dressing in red and his attendant, listen to the sermon.

- States of Good Reincarnation: the third section is further divided into four small squares, each portraying one of four classes of Chinese society in order to capture what seems to be the daily life of the Chinese Manichaean laity. From left to right, the first scene represents itinerant labourers; the second, craftsmen; the third, farmers, and the fourth, aristocrats.

.jpg.webp)

- The Light Maiden's Intervention in a Judgement: the fourth scene shows a judge seated behind a desk surrounded by his aides in a pavilion on an elevated platform, to the front of which two pairs of demons lead their captives to hear their fates. In the upper left corner, the Maiden of Light arrives on a cloud formation with two attendants, to intervene on behalf of the man about to be judged. This section is a depiction of the Manichaean view of judgement after death. The French historian Étienne de la Vaissière compared the judgement scene with that displayed on the Sogdian Wirkak's sarcophagus, and concluded that they are strikingly similar.[6]

- States of Bad Reincarnation: the final scene depicting four fearful images of hell that include, from left to right, a demon shooting arrows at a person suspended from a red frame in the upper left corner; a person hung upside down and being dismembered by two demons; a fiery wheel rolled over a person; and lastly a group of demons waiting for their next victims.

Analysis

Zsuzsanna Gulácsi states in her article A Visual Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation:

The Manichaean origin of this Chinese painting is unquestionable for three principal reasons: its dedicatory inscription that bestowed the object on a Chinese Manichaean temple most likely at Ningbo, in Zhejiang province; the iconography of its main deity, Mani, as well as that of the elect (Manichaean priests), who are shown in Chinese versions of characteristically Manichaean attire; and the significant amount of documentary evidence on the worship of Manichaean deities (Mani and Jesus) represented in pictorial and sculptural forms by the Manichaean communities of southern China, especially Fujian and Zhejiang provinces, between the 10th and 17th centuries. […] This hanging scroll is clearly not a devotional work of art that was used for the purposes of religious worship. It is dominated by a narrative character displayed throughout its complex pictorial program that relies on a large set of uniquely arranged individual scenes. Although the sequence of the scenes is logical, it is not self-evident. Their comprehension implies a beholder familiar with Manichaean religious teaching. We have seen that various compositional elements, just as a comprehensive theme, unite the individual registers (scenes) into this intricate image that is hardly suitable for casual viewing. Therefore, this silk painting can be best interpreted as a didactic work of art designed as a visual aid for religious instruction. If so, this painting constitutes a prime example of such an image that was used by a Manichaean community in ca. 13th-century southern China, possibly in the region of Ningbo, in Zhejiang province.[4]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Detail of the main register: the Mani statue

Detail of the main register: the Mani statue.jpg.webp) Detail of the fourth register: the judgement scene

Detail of the fourth register: the judgement scene.jpg.webp) Detail of the fourth register: the judgement scene

Detail of the fourth register: the judgement scene

Excursus

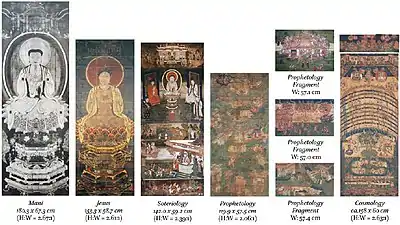

Eight silk hanging scrolls with Manichaean didactic images from southern China from between the 12th and the 15th centuries, which can be divided into four categories:

- Mono-scenic icons

- Icon of Mani

- Painting of the Buddha Jesus

- Soteriology scroll

- Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation

- Prophetology scrolls

- Mani's Parents

- Mani's Birth

- Episodes from Mani's Missionary Work

- Mani's Community Established

- Cosmology scroll

See also

References

- Gulácsi, Zsuzsanna (2015). Mani's Pictures: The Didactic Images of the Manichaeans from Sasanian Mesopotamia to Uygur Central Asia and Tang-Ming China. "Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies" series. 90. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 245. ISBN 9789004308947.

- "「六道図(大和文華館)」をめぐって" (PDF). kintetsu-g-hd.co.jp (in Japanese). 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- Ma, Xiaohe (2014). 霞浦文書研究 [A Study of the Xiapu Manichaean Manuscripts] (PDF) (in Chinese). Lanzhou: Lanzhou University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9787311046699.

- Gulácsi, Zsuzsanna (2008). "A Visual Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation: A Contextualized Reading of a Chinese Manichaean Silk Painting in the Collection of the Yamato Bunkakan in Nara, Japan". academia.edu. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- Gulácsi, Zsuzsanna (2011). "Searching for Mani's Picture-Book in Textual and Pictorial Sources". Heidelberg University Publishing. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- La Vaissière, Étienne de (2015). "Wirkak: Manichaean, Zoroastrian, Khurramî?". academia.edu: 100. Retrieved 27 November 2018.