Sentry program

Sentry, known for most of its lifetime as LoADS for Low Altitude Defense System,[lower-alpha 1] was a short-range anti-ballistic missile (ABM) design made by the US Army during the 1970s. It was proposed as a defensive weapon that would be used in concert with the MX missile, a US Air Force ICBM that was under development.

The LoADS concept was one of a number of proposals that were made as part of a larger and acrimonious debate over the best way to base the MX missile. It was believed that by about 1980 Soviet ICBMs would improve to the point where it was possible to attack US ICBMs while they were still in their silos. A number of warfighting scenarios suggested that a surprise attack would significantly reduce the US stockpile and greatly blunt any counterattack. In the case of the MX, a single successful strike on a silo would mean ten warheads would not reach the USSR, making these extremely valuable targets. To ensure such an attack would fail, at least to the point where the Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) would be maintained, a wide variety of basing options were considered that would guarantee the survival of at least dozens of MX's.

One way to improve the survival of the ICBM force would be to actively defend it with an ABM system. However, the 1972 ABM treaty greatly limited the number and geographical deployment of any ABM, with the aim of preventing whole-country protection and thus ensuring MAD. LoADS addressed these limitations by being deployed along with the radars and engagement computers needed to make a successful attack at only very short ranges, 50,000 feet (15 km) or less. The entire system was packed into a cylinder that looked like an MX and would be shuffled between the silos. As the LoADS could be in any of the silos at a particular missile site, the enemy would have to expend two warheads on every silo to ensure a hit, as one would be assumed lost to LoADS. This would not stop a successful counterforce attack, but it would make it significantly more expensive in terms of the number of warheads used, potentially requiring more warheads than the Soviets had.

With President Jimmy Carter's decision to base the MX in a series of less-hardened horizontal silos in 1977, LoADS development was accelerated. The system as a whole was renamed Sentry, with the missile becoming the Baseline Terminal Defense System, or BTDS. Work on MX and Sentry was further accelerated by incoming President Ronald Reagan in 1981. However, after another review of the MX program, Reagan chose a different MX deployment concept and cancelled Sentry, stating that it would violate the ABM treaty. As the questionable security of the MX once again became an issue, Reagan briefly entertained an even shorter-range system known as Swarmjet, before the entire MX program was severely curtailed with the ending of the Cold War.

Background

ICBM vulnerability

Early ICBMs had accuracy on the order of 1 to 3 miles (1.6–4.8 km),[2] which made them useful against only the largest targets. Through the 1960s this was progressively improved, and the US estimated that the Soviets would have "substantial" capability[3] of directly attacking US missile silos by the 1980 time frame.[4]

This led to a worrying scenario coming to dominate US strategic thinking through the 1970s and 80s. If the Soviets launched a sneak attack on the US using only a portion of their missile fleet, about 1⁄3, aimed solely at US silos and airbases, they could hope to destroy as much as 90% of the US's fleet.[3] This attack would not kill many civilians, and leave the US with only a few ICBMs and bombers, along with the US Navy's Submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) fleet. However, the SLBMs of that era were not accurate enough to attack missile silos, the US would not be able to respond with a counterforce attack against the substantial numbers of remaining Soviet ICBMs. The only option left would be a general attack on Soviet cities, which would cause the Soviets to respond in kind with their remaining fleet. In this situation, the Soviets would be in an extremely advantageous position for a negotiated peace.[5]

When faced with such an attack, it might not be immediately clear what the targets are. The only way to be sure would be to wait until well into the attack and then respond in kind. This took long enough that some portion of the US fleet would be caught on the ground, and this "retaliation after ride-out" concept was considered too risky.[6] Instead, the US policy moved to launch on warning, where they would respond to an attack as soon as it was clear one was in the making. This was not ideal, as it required them to maintain a high alert level that increased the risk of an accidental launch.[7]

Missile, Experimental

In 1964 the Air Force issued a contract to TRW to consider the problem of ICBM survivability under the name "Golden Arrow", looking for ways to make their own missiles as invulnerable as the Navy's.[8] Ideally, the US ICBM fleet should be able to ride out an attack and then launch a response, which would require as many as 1,000 warheads, one for each Soviet ICBM silo.[9] Not only did they have to survive, but they had to have the ability to be quickly retargeted so the surviving US missiles could be aimed only at the remaining Soviet missiles, not empty silos.[10]

One early conclusion was that it was possible to build missile silos that would survive any conceivable warhead exploding at a distance of 1 mile (1.6 km). It was assumed that Soviet warheads during the late 1970s would have accuracy better than one mile, so the question became how to ensure the warheads would not approach within that distance. Among the many solutions studied, one quickly rose to the top, the idea of valley basing. This would rely on the physical barrier presented by surrounding hills or mountains to keep warheads away from the silos in the valleys between them. Warheads approach on a shallow trajectory, so mountains or mesas with steep sides would mean the warhead would impact the terrain before reaching the silo.[11]

TRW suggested building three bases with thirty missiles each, and estimated that one of the three bases would survive an all-out counterforce attack. To ensure that 600 warheads would survive, each missile would have to carry about 20 warheads.[12] These studies led to the Missile, Experimental, or MX, project, which started in 1971.[13] The design rapidly firmed up, emerging with ten-warheads on more missiles in order to raise the survivors to 1,000 warheads. But the basing became not so much a specific concept as a catch-all program for every possible concept, from railway deployments, to underground racetracks, to mobile systems. A review of the options written in the mid-1970s ran into hundreds of pages.[14]

Hardpoint and Hardsite

Through the 1950s and 60s, the US Army had been developing ABM systems as a defense against the ICBM. At first these were tasked with countering a force of dozens or maybe 100 warheads, targeted against US cities and large industrial sites. This was seen as a relatively simple task not unlike the Army's existing anti-aircraft role. However, as the numbers of ICBMs in the Soviet forces rapidly grew, the price of implementing such a system quickly ran out of control, reaching $40 billion ($315 billion in 2021), a significant amount of the total budget of the US Department of Defense.[15]

ARPA was asked to consider the problem of using the technology in a cost-effective way, and noticed one possible application. As Soviet warheads were accurate to within only a few kilometers, and they had to fall within less than a kilometer to kill a missile silo, that meant the Soviets would have to launch several warheads at every US silo in a counterforce attack. The defender had a significant advantage here; they could watch the incoming warheads, see if any were going to come within the lethal range of a silo, and then shoot just those ones. This meant a small number of ABMs would be effective against a huge number of Soviet warheads.[16]

ARPA began researching such a system under the name Hardpoint. To ensure they shot only at valid targets, it had to generate very accurate tracks for the enemy warheads. They also had only seconds to develop that track and launch a missile, assuming that that air would be filled with nuclear explosions that would render higher altitudes opaque to radar, an effect known as nuclear blackout. They began development of a new radar known as the Hardpoint Demonstration Array Radar, or HAPDAR, and a new extremely high-speed missile known as HIBEX. The entire engagement would last just over two seconds, with the intercept taking place at about 20,000 feet (6,100 m) altitude.[16] They later added a second stage to HIBEX known as UPSTAGE, demonstrating over 300 g of lateral acceleration, allowing it to counter maneuvering warheads.[17]

ARPA released its Hardpoint study in 1965. It presented a way for the Army to offer an effective ABM system at a reasonable cost. At the same time, it would ensure that the Air Force's missiles would survive any sort of small-scale attack envisioned by the military planners. This led to a series of Army-Air Force studies under the name Hardsite. Hardsite initially considered the idea of using the existing Nike-X hardware being proposed around large cities to deliberately offer additional protection to Air Force and other military bases in the area. A second series of studies considered cut-down deployments to protect remote bases, like the missile fields. This later concept quickly captured the majority of follow-up work.[18]

ABM treaty

Robert McNamara felt that deploying an ABM system would simply prompt the Soviets to built more ICBMs to overwhelm it, leading to a new arms race. He also felt that more missiles meant more chances for an accidental launch, which would actually increase the change of a war and lower overall security.[19] McNamara constantly delaying deployment of Nike-X, but faced increasing criticism for doing so. When the Chinese tested their first H-bomb in 1967, McNamara announced a much smaller deployment known as Sentinel as a "Chinese oriented" system.[20]

The President also offered to hold off construction on Sentinel if the Soviets did the same. As the Soviets continued construction of their ABM at Moscow, the President ordered the construction of the first Sentinel site outside Boston. This was met by a firestorm of protest on the part of local citizens who were not happy about a nuclear missile base being built literally in their back yard.[21]

The incoming President Nixon was forced to realign the system to something more similar to Hardsite, using the Nike-X systems for the defense of the Minuteman fields in a new system known as Safeguard. This placed the launch sites in distant locations that were less controversial.[22]

In the midst of construction of the first two Safeguard sites, the Soviets returned to the negotiations. This led to the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, limiting each side to a total of 100 interceptor missiles located in up to two ABM bases, and amending that to only one base in 1974. The Soviets chose to complete their system around Moscow while the US continued with construction of one of the Safeguard sites outside Grand Forks, North Dakota. The argument for and against the Safeguard system continued both in the military and public arenas, and the system was ultimately shut down in 1975 after only one day of official operation.[23]

LoADS

Continuing work

As a hedge against the possibility of the Soviets "breaking out" of the ABM treaty, the Army was given the go-ahead to continue development of ABM technologies, focusing on the Safeguard-like concept of defending the missile fields. The Army responded with two concepts, updates to the original Safeguard using a new radar and upgraded Sprint II missile, and a new concept for a high-altitude interceptor that would use hit-to-kill instead of a nuclear warhead.[24] Work on the former, known as Site Defence of Minuteman, went as far as building a radar at the Army's testing site on Meck Island in the Kwajalein Atoll, but work on this program ended in 1974 when it was clear the treaty was going to be followed by both countries.[24]

Work on MX also continued, and by the mid-1970s the preferred MX basing mode was the Multiple Protective Shelter (MPS) concept. In this system each MX missile would be installed in a network of hardened shelters, 23 in most plans, and moved between them at random. The transports would be camouflaged and duplicated so the Soviets would not know where the missiles were. A counterforce attack would thus require the Soviets to expend 23 warheads for every MX missile to ensure destruction. With a total of 4,500 shelters and 200 missiles moving between them, the system could soak up a significant portion of the Soviet's 5,928 ICBM warheads and survive.[25] In this basing mode, a system like Safeguard was of little use. If the Soviets needed to fire 4,500 warheads to ensure the destruction of the MX force, expending another 100 to soak up an ABM system was of little consequence.[26]

Through the 1970s a number of alternative concepts to defend the silos had been proposed. Richard Garwin outlined a series of alternatives to large-scale ABM systems like Safeguard.[27] Among these ideas were a "bed of nails" consisting of vertical steel spikes surrounding the silo that would destroy the warhead before it hit the ground and triggered, jamming systems to interrupt radar fuses, the dust defense where small nuclear warheads would be set off while the warheads approached and throw huge amounts of dust into the air that would abrade the warheads, and a non-nuclear version of the same concept, the "curtain of steel pellets".[28] The last of these was picked up by Bernard Feld and Kosta Tsipis in a major article in Scientific American in 1979. They proposed replacing the shotgun-like projectiles with swarms of small unguided rockets that would fire at a range of about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi). As they were unguided, they suggested that they would not be considered interceptor missiles under the ABM treaty, but also suggested that a renegotiation might be required.[29]

The Army picked up these options, developing two concepts. The first, Project Quick-Shot, was basically identical to the Feld and Tsipis version, although they did consider some sort of low-cost guidance system as well.[29] A second concept launched optical trackers into space in the path of the incoming missiles, and used their data to fine-tune the launch of unguided rockets that would work at longer ranges. As this had no radar component, it would bypass provisions in the ABM treaty over the number and placement of radar sites.[30]

However, they also considered a more conventional concept using what was essentially a version of HIBEX and UPSTAGE,[17] and in 1976 they placed a contract with McDonnell Douglas to study a low-altitude concept under the name ST-2, using a nuclear-tipped missile.[30] This proved the most interesting, and led to the LoADS program in 1977.[31]

LoADS concept

LoADS proposed placing one interceptor in one of the decoy shelters, thus every set of 23 shelters would have one MX, one LoADS and 21 decoys. At first glance it might appear that only one additional enemy warhead would be needed, using up the LoADS interceptor. However, only the defender knew where the MX was, and LoADS would only fire at the single warhead seen approaching that shelter. That meant that the MX would almost definitely survive a single warhead attack. In order to be sure the MX was hit, the Soviets would have to attack every shelter with two warheads, assuming one would be lost to the LoADS.[32] For a typical 23-site MPS, 46 warheads would be needed,[33] so if LoADS remained within the 100-interceptor limit of the ABM treaty, 4,600 warheads would be needed to attack just one-half of the 200-strong MX fleet, leaving 100 missiles and 1,000 warheads in the US counterattack. An attack against the entire fleet would require them to break the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks limits on the number of offensive warheads.[25]

This proposal, for the first time, made a solid argument for ABM deployment as a counterforce weapon. Previously each ABM required a corresponding warhead to offset it, but with LoADS and MPS, a single ABM required multiple warheads to offset it.[32] The same end could be achieved by simply building more shelters as well, but the size of the proposed MPS network already took up large portions of Nevada and Utah, and adding more would not be easy. Even a high unit price, LoADS would still be less expensive than building double the number of shelters.[33] Additionally, as each set of MPS shelters, or cells, would have only a single LoADS, the problems with nuclear blackout causing problems for follow-up shots was not an issue, a problem that had never been solved in Safeguard-like solutions.[34]

However, there was a concern in regards to the ABM treaty, involving its use of radars. In order to ensure ABM systems would be suitable for point defense only, the ABM treaty limited the number and placement of radar systems. LoADS had a radar with each missile, but these were very short-range and could not be considered part of a wide-area system, although observers suggested the Soviets would claim otherwise.[1] More importantly, the 1974 amendment to the treaty required those radars to be in the vicinity of Grand Forks, which would not help MPS, which was located well over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) to the southwest. The Army thus developed LoADS strictly as a technology demonstration program, with the option of rapid construction in case the ABM treaty ended.[35] Costs of a deployed system was estimated to be $8.63 billion in 1980 (27 billion in 2021).[36]

Sentry

Seeking to lower the spiralling cost of the MX system, which had reached at least $35 billion by the end of the 1970s,[37] Jimmy Carter announced a greatly simplified deployment using simpler silos and reduced number of false launchers. The launchers changed from vertical to horizontal, which would reduce the cost of building them and make it simpler to rapidly move the missiles in and out of the silos without it being easily seen. LoADS was adapted to work in these new shelters, and by the late 1970s was known as the Baseline Terminal Defense System.[1]

But Carter's choice had only just been made when Ronald Reagan won the presidency and set about re-examining the MX plans. In October 1981 they announced MX deployment would be sped up, cancelling the MPS basing and recommending the missiles temporarily be placed in existing Titan II and Minuteman silos until a final solution could be decided on. Work on LoADS continued, in and June 1982 was renamed Sentry. The program was told to be prepared to go into production on short notice.[32]

Work on the high-altitude non-nuclear concept was also ongoing through this period, and would ultimately be demonstrated in 1984's Homing Overlay Experiment.[26]

Cancellation

On 22 November 1982, Reagan held another conference on the MX issue. He announced that MPS was being abandoned and replaced by the Dense Pack concept. This would consist of new super-hardened silos that could withstand very close hits, packed together in groups of 100. The theory was that a warhead attacking any one of the silos would destroy others near it when it exploded, a concept known as nuclear fratricide. One of the arguments in favor of Dense Pack was that it "lends itself to ABM defense a little better".[1]

Nevertheless, Reagan went on to state that "we do not wish to embark on any course of action that could endanger the current ABM treaty so long as it is observed by the Soviet Union... we do not wish to build even the minimal ABM system allowed us by the treaty." In February 1983, Sentry was officially cancelled.[38]

Work on the radar system continued and was later renamed the Terminal Imaging Radar, with an expanded mission to provide accurate tracks over a wide area. Technologies from this program ultimately led to the X-band radar.[32][39] Work on the warhead design also continued, but was later moved to a "third generation" design, and in 1983 the Department of Energy noted there were nine such designs under consideration.[38]

Description

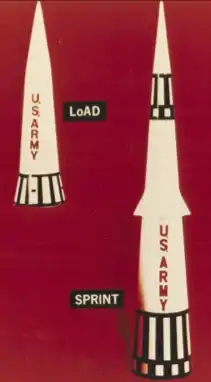

The baseline LoADS design was a single-stage missile consisting of three stacked conical sections; a pointed conical nose-cone, a slightly flared cylinder through the midsection forming the majority of the missile body, and a flared rear section surrounding the rocket nozzles. It was very similar to the upper stage of the Sprint missile, although lacking the Sprint's small aerodynamic fins.[24]

Each missile would be packaged into a container known as the "Defense Unit" that would look identical to the MX container.[40] The LoADS was much smaller than MX, which allowed the container to hold the missile, communications, radar and ejector systems needed to launch the missile.[32][41] Given warning of an attack, the LoADS would be pushed through the roof of the shelter (or raised in the case of a vertical silo) to reveal its radar and begin searching for incoming warheads. When one was determined to be approaching the location of the MX, LoADS would fire, attacking the warhead at very low altitude, about 40,000 feet (12 km).[42]

LoADS used a nuclear warhead to attack its targets, and its close proximity to the ground when it fired meant it was only able to be used over hardened targets like a missile silo.[24] The Army also worked on hit-to-kill warheads for a mid-range system, but at the time of its cancellation they had not been able to demonstrate the feasibility of this approach.[26]

Notes

- Sometimes known as LoAD, for Low Altitude Defense[1]

References

Citations

- Paine 1982, p. 5.

- Sorenson, H.W. (6 June 1960). Range and Guidance Accuracy Capability of the Atlas Missile System (PDF) (Technical report). p. 12.

- Soule & Davison 1979, p. 2.

- Soule & Davison 1979, p. xvii.

- Lackey, Douglas (1986). "Nuclear Weapons, Politics and Strategy, A Short History". Moral Principles of Nuclear Weapons. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8476-7116-8.

- Blair, Bruce (2011-04-01). The Logic of Accidental Nuclear War. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8157-1711-9.

- Burr, William (April 2001). "Launch on Warning: The Development of U.S. Capabilities, 1959–1979". The National Security Archive. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- Pomeroy 2006, p. 124.

- Soule & Davison 1979, p. 23.

- MacKenzie 1993, p. 203.

- Pomeroy 2006, p. 135.

- Pomeroy 2006, p. 136.

- MacKenzie 1993, pp. 225–226.

- Soule & Davison 1979.

- Ritter, Scott (2010). Dangerous Ground: America's Failed Arms Control Policy, from FDR to Obama. Nation Books. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7867-2743-8.

- Bell Labs 1975, pp. 2–12.

- Van Atta 1991, p. 3-1.

- Bell Labs 1975, pp. 2–13.

- Kent 2008, p. 49.

- McNamara, Robert (December 1967). "Remarks by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, September 18, 1967". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: 26–31.

- Clearwater, John (December 1996). Johnson, McNamara, and the Birth of SALT and the ABM Treaty 1963–1969. Universal-Publishers. pp. 117, 123. ISBN 978-1-58112-062-2.

- Kitchens III, James (6 September 1978). A History of the Huntsville Division, 15 October 1967 – 31 December 1976 (PDF). US Army Corps of Engineers. p. 32.

- Burns, Richard (2010). The Missile Defense Systems of George W. Bush: A Critical Assessment. ABC-CLIO. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-313-38466-0.

- Office 1986, p. 57.

- Soule & Davison 1979, p. xviii.

- Office 1986, p. 58.

- Garwin, Richard (Autumn 1976). "Effective Military Technology for the 1980s" (PDF). International Security. 1 (2): 50–77. doi:10.2307/2538499. JSTOR 2538499. S2CID 154011066.

- Baucom 1989, p. 218.

- Baucom 1989, p. 219.

- Baucom 1989, p. 220.

- Department of the Army Historical Summary: FY 1979. pp. 179, 183–184.

- Lang 2007, p. 14.

- Woolf 1981, p. 112.

- Woolf 1981, p. 116.

- Woolf 1981, p. 114.

- Woolf 1981, p. 125.

- Soule & Davison 1979, p. xxii.

- Arkin, Cochran & Hoenig 1984, p. 14s.

- "Terminal Imaging Radar (TIR)". Global Security.

- Woolf 1981, p. 118.

- Woolf 1981, p. 119.

- Woolf 1981, p. 120.

Bibliography

- Arkin, William; Cochran, Thomas; Hoenig, Milton (August–September 1984). "Resource Paper on the US Nuclear Arsenal". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. pp. 3s–15s.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baucom, Donald (December 1989). Origins of the Strategic Defense Initiative: Ballistic Missile Defense, 1944–1983. Strategic Defense Initiative Organization.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bell Labs (October 1975). ABM Research and Development at Bell Laboratories, Project History (PDF) (Technical report).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kent, Glenn (2008). Thinking About America's Defense. RAND. ISBN 978-0-8330-4452-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lang, Sharon (June–July 2007). "From LoAD to Sentry: Defense of the MX" (PDF). The Eagle. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacKenzie, Donald (1993). Inventing Accuracy: a historical sociology of nuclear missile guidance. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-63147-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strategic Defenses: Two Reports by the Office of Technology Assessment. Office of Technology Assessment. 1986. ISBN 978-1-4008-5509-4.

- Paine, Christopher (October 1982). "Arms buildup". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. pp. 5–8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pomeroy, Steven (11 August 2006). Echos That Never Were: American Mobile Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, 1956–1983 (PDF). US Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2016-11-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Soule, Robert; Davison, Richard (June 1979). The MX Missile and Multiple Protective Structure Basing: Long-Term Budgetary Implications (PDF) (Technical report). Congressional Budget Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Atta, Richard (1991). HIBEX - UPSTAGE (PDF). Institute for Defense Analysis.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woolf, Harry (September 1981). MX Missile Basing (PDF) (Technical report). Princeton Institute for Advanced Study.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)