Sant'Alessandro, Lucca

Sant’Alessandro Maggiore is a Romanesque-style, Roman Catholic parish church in Lucca, region of Tuscany, Italy.

| Church of Saint Alexander Sant'Alessandro (in Italian) | |

|---|---|

Façade of the church | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Province | Archdiose of Lucca |

| Rite | Latin Rite |

| Status | Parish church |

| Location | |

| Location | Lucca, Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 43°50′31.97″N 10°30′5.39″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 9th century |

| Website | |

| www | |

History

First mentioned in a document dated 893, the layout is that of a Romanesque basilica, with little decoration, giving the facade a sober classicism.[1][2]

The present building, however, contains the structures of an older church,[3] whose date of construction is still a matter of controversy, and whose features are surprisingly close to those of Roman architecture:[4] This church is a rare and good preserved example of medieval classicism, an evidence of survival in Italy, during the Dark Ages, of Roman architectural tradition. The small building can be compared only with monuments as the Baptistry in Florence or the Basilica of San Salvatore in Spoleto.

Description

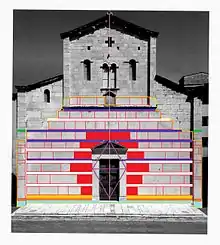

The building is entirely covered with perfectly polished limestone slabs and arranged in alternately high and low bands, according to an order evoking the monuments of Antiquity, this alternation has no purely decorative but compositional value: in the oldest parts of the façade, the lower bands stand in white "partition" bands, which simply ripple the surface and in gray "projecton" bands, which project horizontally the structural nodes. The symmetrical layout of the façade stones around the portal is comparable to that of the Visigothic, but very much restored, Chapel of São Frutuoso de Montélios near Braga, attributed to the VII century. In our case, however, the original apparatus is very well preserved and presents even more regular elements, which have no clue in the Romanesque churches of Lucca. Moreover, the entire composition of the façade is understandable only within the parameters of ancient architecture, as seen in the diagram that shows the different elements in color: the original façade (surrounded by yellow) rests on a podium, today undercut, roughly pointed at the tip of a chisel (highlighted in celestial), on this runs a stephole (in orange) that with the function of plinth (and as such is supported by the angular risers) departs from the portal and fascinates the whole church, similar to the attic base (yellow ocher) that overlaps it. On these basic elements, which overlap each other with a slight backslash and with an ever larger surface finish, the straight edge is set to perfectly polished alternating bands, similar to the opus quadratum pseudoisodomum of the ancient buildings. The scheme shows both the horizontal projection bands of the structural elements (in blue) and the simple partition bands (blank). The second projection line from the top, due to the late elevation of the church, does not correspond today to any structural element, but originally combined the terminal capitals (dark green) of the lower angular risers. The contour of the slabs (highlighted in red) allowes them to evaluate the symmetrical arrangement with respect to the vertical axis passing through the portal, generating element of the whole façade : up to the pedestal height the plates correspond to the right and left numbers; the joint of the two slabs above the gable materializes the axis of the composition; the ends of the bands corresponding to the architrave are completed by symmetrical, overlapping vertical slats, and symmetrical is the mounting of the angular risers. Around the portal (red) twelve large plates are formed to form a hexagon and appear to radiate from the portal itself, whose proportions are governed by a double equilater triangle (violet). The diagram also shows in clear green the position of the decorative laths on the side of the pediment and that of the bases of the columns of the loggia today missing. From all these elements so highlighted and from the triangular path that had to adjust their proportions, the appearance of the primitive façade, which is lower than the present and much closer to the forms of ancient architecture, can be reconstructed with good approximation.

The apertures framing sculpted details — within this rigorously geometric design — are also directly derived from the Ancient Roman architecture. This interpenetration of a static, geometric system can also be seen in the arches within the church, where the white and coloured stone is arranged symmetrically throughout, as is found in sixth and seventh century buildings such as the Mausoleum of Theodoric in Ravenna and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (or in peristyle of Diocletian's Palace in Split, ca. 300 AD). As is also to be seen in the early Christian basilicas in Rome, the interior of the church is divided into functional areas and crossed by a liturgical route which is clearly indicated, down to the smallest detail, by variations in the colour of the marble and by the different types of capital in pairs which match across the nave. There are further reminders in the taste for varietas which (in the same strictly symmetrical context) informs all the sculpted ornamentation, whose careful variations have parallels in the Basilica of San Salvatore in Spoleto and in the capitals of the Temple of Saturn in Rome, rebuilt in the fourth century A.D.

Finally, the character of the sculpture is unusual. On the one hand, the vegetal elements -geometric, flat and with finely incised details — are set out according to a predominantly paratactic/symmetrical system (such elements are typical of sculpture of later antiquity), while on the other, the designs which are repeatedly copied (including unusual Corinthian variations and rare motifs of the Augustan Age) are typical of the first and second centuries A.D. While the most recent parts of the building correspond to twelfth century architecture (in particular the work of Biduino and his school), the unusual features of the older Sant’Alessandro make it an isolated example in local medieval architecture.[5][6][7][8]

References

- Ragghianti, Carlo Ludovico (1949). "Architettura lucchese e architettura pisana". Critica d'arte (in Italian). 28.

- Taddei, Carlotta (2005). "Lucca tra XI e XII secolo. Territorio, architetture, città". Quaderni di Storia dell'Arte" (in Italian). 23: 117–156.

- Silva, Romano (1987). La chiesa di Sant'Alessandro Maggiore in Lucca (in Italian).

- Seidel, Max; Silva, Romano, eds. (2001). "La chiesa di Sant'Alessandro tra archeologia e ricerca documentaria". Lucca città d'arte e i suoi archivi. Opere d'arte e testimonianze documentarie dal Medioevo al Novecento (in Italian). pp. 59–96.

- Carrai, Giampaolo (2002). Tradizione tardoantica e derive medievali nella chiesa di Sant'Alessandro a Lucca (in Italian).

- Tigler, Guido (2006). Toscana romanica (in Italian). pp. 245–247.

- Frati, Marco (2014). Architettura romanica a Lucca (XI-XII secolo). Snodi critici e paesaggi storici, in Chiara Bozzoli - Maria Teresa Filieri (a cura di),Scoperta armonia. Arte medievale a Lucca (in Italian). pp. 177–224.

- Carrai, Giampaolo (2017). La chiesa di Sant'Alessandro Maggiore a Lucca : un exemplum di architettura sacra come figura teologica (in Italian).

External links

Media related to Sant'Alessandro (Lucca) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sant'Alessandro (Lucca) at Wikimedia Commons- "Church Sant'Alessandro". Lands of Lucca and Versilia. (in English)

- Church of Sant'Alessandro Maggiore

- On site investigation techniques for the structural evaluation of historic masonry buildings (1)

- On site investigation techniques for the structural evaluation of historic masonry buildings (2)