SS United States

SS United States is a retired ocean liner built in 1950–51 for the United States Lines at a cost of $79.4 million.[1] The ship is the largest ocean liner constructed entirely in the United States and the fastest ocean liner to cross the Atlantic in either direction, retaining the Blue Riband for the highest average speed since her maiden voyage in 1952. She was designed by American naval architect William Francis Gibbs and could be converted into a troopship if required by the Navy in time of war. The United States maintained an uninterrupted schedule of transatlantic passenger service until 1969 and was never used as a troopship.

United States docked at Pier 82 in Philadelphia, August 2020 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | United States |

| Owner: | SS United States Conservancy |

| Operator: | United States Lines |

| Port of registry: | New York City |

| Route: | Transatlantic |

| Ordered: | 1949[1] |

| Builder: | Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company[1] |

| Cost: | $79.4 million[1]($636 million in 2019[2]) |

| Yard number: | Hull 488[3] |

| Laid down: | February 8, 1950 |

| Launched: | June 23, 1951[4] |

| Christened: | June 23, 1951[4] |

| Maiden voyage: | July 3, 1952 |

| Out of service: | November 14, 1969[5] |

| Identification: |

|

| Nickname(s): | "The Big U"[6] |

| Fate: | Laid up in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Status: | Sold in 1978 |

| Owner: | Various |

| Acquired: | 1978 |

| Fate: | Laid up in Philadelphia in 1996.[7] |

| Notes: | United States changed ownership multiple times from 1978 to 1996[8] |

| Owner: | SS United States Conservancy |

| Acquired: | February 1, 2011 |

| Status: | Laid up in Philadelphia[9] |

| Notes: | Continual fundraising towards conservation efforts since 2011.[9] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 53,330 GRT |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 101.5 ft (30.9 m) maximum |

| Draft: |

|

| Depth: | 75 ft (23 m) |

| Decks: | 12 |

| Installed power: | |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | |

| Capacity: | 1,928 passengers |

| Crew: | 900 |

SS United States (Steamship) | |

| |

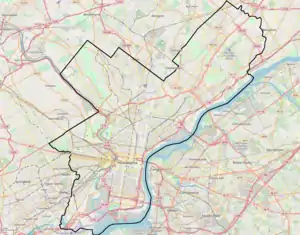

| Location | Pier 82, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 39°55′4.6″N 75°8′12.8″W |

| Architect | William Francis Gibbs |

| NRHP reference No. | 99000609[10] |

| Added to NRHP | June 3, 1999 |

The ship has been sold several times since the 1970s, with each new owner trying unsuccessfully to make the liner profitable. Eventually, the ship's fittings were sold at auction, and hazardous wastes, including asbestos panels throughout the ship, were removed, leaving her almost completely stripped by 1994. Two years later, she was towed to Pier 82 on the Delaware River, in Philadelphia, where she remains today.

Since 2009, a preservation group called the SS United States Conservancy has been raising funds to save the ship. The group purchased her in 2011 and has drawn up several unrealized plans to restore the ship, one of which included turning the ship into a multi-purpose waterfront complex. In 2015, as its funds dwindled, the group began accepting bids to scrap the ship; however, sufficient donations came in via extended fundraising. Large donations have kept the ship berthed at its Philadelphia dock while the group continues to further investigate restoration plans.[11]

Design and construction

Inspired by the service of the British liners RMS Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, which transported hundreds of thousands of US troops to Europe during World War II, the US government sponsored the construction of a large and fast merchant vessel that would be capable of transporting large numbers of soldiers. Designed by American naval architect and marine engineer William Francis Gibbs (1886–1967), the liner's construction was a joint effort by the United States Navy and United States Lines. The US government underwrote $50 million of the $78 million construction cost, with the ship's prospective operators, United States Lines, contributing the remaining $28 million. In exchange, the ship was designed to be easily converted in times of war to a troopship. The ship has a capacity of 15,000 troops, and could also be converted to a hospital ship.[12]

In 1942, during World War II, the French liner SS Normandie, which had been seized by US authorities in New York and renamed the USS Lafayette, caught fire while being converted to a troopship by the US Navy. After millions of gallons of water had been pumped into her in an attempt to extinguish the flames, she capsized onto her port side and came to rest on the mud of the Hudson River at Pier 88, the current site of the New York Passenger Ship Terminal. As a result of this disaster, the design of the United States incorporated the most rigid US Navy standards.[13] To minimize the risk of fire, the designers of United States prescribed using no wood in the ship's framing, accessories, decorations, or interior surfaces, although the galley did feature a wooden butcher's block. Fittings, including all furniture and fabrics, were custom made in glass, metal, and spun-glass fiber, to ensure compliance with fireproofing guidelines set by the US Navy. Asbestos-laden paneling was used extensively in interior structures.[14] The clothes hangers in the luxury cabins were aluminum. The ballroom's grand piano was made from mahogany — although originally specified in aluminum — and accepted only after a demonstration in which gasoline was poured upon the wood and ignited, without the wood itself ever catching fire.[15] Specially commissioned artwork included pieces by fourteen artists, including Nathaniel Choate, muralist Austin M. Purves, Jr., and sculptor Gwen Lux.[16]

The vessel was constructed from 1950 to 1952 at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in Newport News, Virginia. The hull was constructed in a dry dock. United States was built to exacting Navy specifications, which required that the ship be heavily compartmentalized, and have separate engine rooms to optimize wartime survival.[17] A large part of the construction was prefabricated. The ship's hull comprised 183,000 pieces.[18]

The construction of the ship's superstructure involved the most extensive use of aluminum in any construction project up to that time, which posed a galvanic corrosion challenge to the builders in joining the aluminum superstructure to the steel decks below. However, the extensive use of aluminum meant significant weight savings, as well.[19] United States had the most powerful steam turbines of any merchant marine vessel at the time, with a total power of 240,000 shaft horsepower (180 MW) delivered to four 18-foot (5.5 m)-diameter manganese-bronze propellers. The ship was capable of steaming astern at over 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), and could carry enough fuel and stores to steam non-stop for over 10,000 nautical miles (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at a cruising speed of 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph).[20]

History

1952–1996

On her maiden voyage—July 3–7, 1952—United States broke the eastbound transatlantic speed record (held by the RMS Queen Mary for the previous 14 years) by more than 10 hours, making the maiden crossing from the Ambrose lightship at New York Harbor to Bishop Rock off Cornwall, UK in 3 days, 10 hours, 40 minutes at an average speed of 35.59 knots (65.91 km/h; 40.96 mph).[21] and winning the coveted Blue Riband.[22] On her return voyage United States also broke the westbound transatlantic speed record, also held by RMS Queen Mary, by returning to America in 3 days 12 hours and 12 minutes at an average speed of 34.51 knots (63.91 km/h; 39.71 mph). In New York her owners were awarded the Hales Trophy, the tangible expression of the Blue Riband competition.[23] The maximum speed attained for United States is disputed as it was once held as a military secret.[24] The issue stems from an alleged value of 43 knots (80 km/h; 49 mph) that was leaked to reporters by engineers after the first speed trial. In a 1991 issue of Popular Mechanics, author Mark G. Carbonaro wrote that while she could do 43 knots (80 km/h; 49 mph) it was never attained.[25] Other sources, including a paper by John J. McMullen & Associates, places the ship's highest possible sustained top speed at 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph).[26]

By the mid-to-late 1960s, the market for transatlantic travel by ship had dwindled—America was sold in 1964, Queen Mary was retired in 1967, and Queen Elizabeth in 1968—and United States was no longer profitable. While United States was at Newport News for an annual overhaul in 1969, United States Lines decided to withdraw her from service, leaving the ship docked at the port. After a few years, the ship was relocated to Norfolk, Virginia. Subsequently, ownership passed between several companies.[27]

In 1977, a group headed by Harry Katz sought to purchase the ship and dock it in Atlantic City, New Jersey, where it would be used as a hotel and casino. However, nothing came of the plan.[28] The vessel was sold in the following year for $5 million to a group headed by Seattle developer Richard H. Hadley, who hoped to revitalize the liner in a time share cruise ship format.[29] In 1979, Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) was reportedly interested in purchasing the ship and converting her into a cruise ship for cruises in the Caribbean, but decided on purchasing the former SS France instead. During the 1980s, United States was considered by the US Navy to be converted into a troopship or a hospital ship, to be called USS United States. This plan never materialized, being dropped in favor of converting two San Clemente class supertankers.[30]

In 1984, to pay creditors, the ship's remaining fittings and furniture were sold at auction in Norfolk. Some of the furniture was installed in Windmill Point, a restaurant in Nags Head, North Carolina. Richard Hadley's plan of a time-share style cruise ship eventually failed financially, and the ship, which had been seized by US marshals, was put up for auction by MARAD in 1992. At auction, Marmara Marine Inc.—which was headed by Edward Cantor and Fred Mayer, but with Juliedi Sadikoglu, of the Turkish shipping family, as majority owner—purchased the ship for $2.6 million.[31][32] The ship was towed to Turkey and then Ukraine, where, in Sevastopol Shipyard, she underwent asbestos removal which lasted from 1993 to 1994.[33] The interior of the ship was almost completely stripped during this time. In the US, no plans could be finalized for repurposing the vessel, and in 1996, the United States was towed to South Philadelphia.[34]

1997–2010

In November 1997, Edward Cantor purchased the ship for $6 million.[35] Two years later, the SS United States Foundation and the SS United States Conservancy (then known as the SS United States Preservation Society, Inc.) succeeded in having the ship placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2003, Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) purchased the ship at auction from Cantor's estate after his death. NCL's intent was to fully restore the ship to a service role in their newly announced American-flagged Hawaiian passenger service called NCL America. The United States is one of the few ships eligible to enter such service because of the Passenger Service Act, which requires that any vessel engaged in domestic commerce be built and flagged in the US and operated by a predominantly American crew.[36] NCL began an extensive technical review in late 2003, after which they stated that the ship was in sound condition. The cruise line cataloged over 100 boxes of the ship's blueprints.[37] In August 2004, NCL commenced feasibility studies regarding a new build-out of the vessel; and in May 2006, Tan Sri Lim Kok Thay, chairman of Malaysia-based Star Cruises (the owner of NCL), stated that SS United States would be coming back as the fourth ship for NCL after refurbishment.[38] Meanwhile, the Windmill Point restaurant, which had contained some of the original furniture from the United States, closed in 2007. The ship's furniture was donated to the Mariners' Museum and Christopher Newport University, both in Newport News, Virginia.[39]

When NCL America first began operation in Hawaii, it used the ships Pride of America, Pride of Aloha, and Pride of Hawaii, rather than United States. NCL America later withdrew Pride of Aloha and Pride of Hawaii from its Hawaiian service. In February 2009, it was reported that SS United States would "soon be listed for sale".[40][41]

The SS United States Conservancy was then created that year as a group trying to save United States by raising funds to purchase her.[42] On July 30, 2009, H. F. Lenfest, a Philadelphia media entrepreneur and philanthropist, pledged a matching grant of $300,000 to help the United States Conservancy purchase the vessel from Star Cruises.[43] A noteworthy supporter, former US president Bill Clinton, has also endorsed rescue efforts to save the ship, having sailed on her himself in 1968.[17][44]

In March 2010, it was reported that bids for the ship, to be sold for scrap, were being accepted. Norwegian Cruise Lines, in a press release, noted that there were large costs associated with keeping United States afloat in her current state—around $800,000 a year—and that, as the SS United States Conservancy was not able to tender an offer for the ship, the company was actively seeking a "suitable buyer".[45] By May 7, 2010, over $50,000 was raised by The SS United States Conservancy.[46] The Conservancy eventually bought SS United States from NCL in February 2011 for a reported $3 million with the help of money donated by philanthropist H.F. Lenfest.[47] The group had funds to last 20 months (from July 1, 2010) that were to go to supporting a development plan to clean the ship of toxins and make the ship financially self-supporting, possibly as a hotel or other development project.[48][49] SS United States Conservancy executive director Dan McSweeney stated that he planned on placing the ship at possible locations that include Philadelphia, New York City, and Miami.[48][50]

In November 2010, the Conservancy announced a plan to develop a "multi-purpose waterfront complex" with hotels, restaurants, and a casino along the Delaware River in South Philadelphia at the proposed location of the stalled Foxwoods Casino project. The results of a detailed study of the site were revealed in late November 2010, in advance of Pennsylvania's December 10, 2010, deadline for a deal aimed at Harrah's Entertainment taking over the casino project. However, the Conservancy's deal soon collapsed, when on December 16, 2010, the Gaming Control Board voted to revoke the casino's license.[51]

2011–2015

The SS United States Conservancy assumed ownership of United States on February 1, 2011.[7][52] Talks about possibly locating the ship in Philadelphia, New York City, or Miami continued into March. In New York City, negotiations with a developer were underway for the ship to become part of Vision 2020, a waterfront redevelopment plan costing $3.3 billion. In Miami, Ocean Group, in Coral Gables, was interested in putting the ship in a slip on the north side of American Airlines Arena.[53] With an additional $5.8 million donation from H. F. Lenfest, the conservancy had about 18 months from March 2011 to make the ship a public attraction.[53] On August 5, 2011, the SS United States Conservancy announced that after conducting two studies focused on placing the ship in Philadelphia, it was "not likely to work there for a variety of reasons". However, discussions to locate the ship at her original home port of New York, as a stationary attraction, were reported to be ongoing.[54] The Conservancy's grant specifies that the refit and restoration must be done in the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard for the benefit of the Philadelphia economy, regardless of her eventual mooring site.

On February 7, 2012, preliminary work began on the restoration project to prepare the ship for her eventual rebuild, although a contract had not yet been signed.[55] In April 2012, a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) was released as the start of an aggressive search for a developer for the ship. A Request for Proposals (RFP) was issued in May.[56] In July 2012, the SS United States Conservancy launched a new online campaign called "Save the United States", a blend of social networking and micro-fundraising that allowed donors to sponsor square inches of a virtual ship for redevelopment, while allowing them to upload photos and stories about their experience with the ship. The Conservancy announced that donors to the virtual ship would be featured in an interactive "Wall of Honor" aboard the future SS United States museum.[57][58]

By the end of 2012, a developer was to be chosen, who would put the ship in a selected city by summer 2013.[59] In November 2013, it was reported that the ship was undergoing a "below-the-deck" makeover, which lasted into 2014, in order to make the ship more appealing to developers as a dockside attraction. The SS United States Conservancy was warned that if its plans were not realized quickly, there might be no choice but to sell the ship for scrap.[60] In January 2014, obsolete pieces of the ship were sold to keep up with the $80,000-a-month maintenance costs. Enough money was raised to keep the ship going for another six months, with the hope of finding someone committed to the project, New York City still being the likeliest location.[61]

In August 2014, the ship was still moored in Philadelphia and costs for the ship's rent amounted to $60,000 a month. It was estimated that it would take $1 billion to return United States to service on the high seas, although a 2016 estimate for restoration as a luxury cruise ship was said to be, "as much as $700 million".[62][63] On September 4, 2014, a final push was made to have the ship bound for New York City. A developer interested in re-purposing the ship as a major waterfront destination made an announcement regarding the move. The Conservancy had only weeks to decide if the ship needed to be sold for scrap.[64] On December 15, 2014, preliminary agreements in support of the redevelopment of SS United States were announced. The agreements included providing for three months of carrying costs, with a timeline and more details to be released sometime in 2015.[65][66] In February 2015, another $250,000 was received by the Conservancy from an anonymous donor which went towards planning an onboard museum.[67]

As of October 2015, the SS United States Conservancy had begun exploring potential bids for scrapping the ship. The group was running out of money to cover the $60,000-per-month cost to dock and maintain the ship. Attempts to re-purpose the ship continued. Ideas included using the ship for hotels, restaurants, or office space. One idea was to install computer servers in the lower decks and link them to software development businesses in office space on the upper decks. However, no firm plans were announced. The conservancy said that if no progress was made by October 31, 2015, they would have no choice but to sell the ship to a "responsible recycler".[68] As the deadline passed it was announced that $100,000 had been raised in October 2015, sparing the ship from immediate danger. By November 23, 2015, it was reported that over $600,000 in donations had been received for care and upkeep, buying time well into the coming year for the SS United States Conservancy to press ahead with a plan to redevelop the vessel.[69]

2016–present

On February 4, 2016, Crystal Cruises announced that it had signed a purchase option for the SS United States. Crystal would cover docking costs, in Philadelphia, for nine months while conducting a feasibility study on returning the ship to service as a cruise ship based in New York City.[70][71] On April 9, 2016, it was announced that 600 artifacts from the SS United States would be returned to the ship from the Mariners' Museum and other donors.[72]

On August 5, 2016, the plan was formally dropped, Crystal Cruises citing the presence of too many technical and commercial challenges. The cruise line then made a donation of $350,000 to help with preservation through the end of the year.[73][74][75] The SS United States Conservancy continued to receive donations, which included one for $150,000 by cruise industry executive Jim Pollin.[9] In January 2018, the conservancy made an appeal to US president Donald Trump to take action regarding "America's Flagship".[76] If the group runs out of money, alternative plans for the ship include sinking it as an artificial reef rather than scrapping her.[9]

On September 20, 2018, the conservancy consulted with Damen Ship Repair & Conversion about redevelopment of the United States. Damen had converted the former ocean liner and cruise ship SS Rotterdam into a hotel and mixed-use development.[77]

On December 10, 2018, the conservancy announced an agreement with the commercial real estate firm RXR Realty, of New York City, to explore options for restoring and redeveloping the ocean liner.[78] In 2015, RXR had expressed interest in developing an out-of-commission ocean liner as a hotel and event venue at Pier 57 in New York.[79] The conservancy requires that any redevelopment plan preserve the ship's profile and exterior design, and include approximately 25,000 sq ft (2,323 m2) for an onboard museum.[77] RXR's press release about the United States stated that multiple locations would be considered, depending on the viability of restoration plans.[78][79]

In March 2020, RXR Realty announced its plans to repurpose the ocean liner as a permanently-moored 600,000 sq ft (55,740 m2) hospitality and cultural space, requesting expressions of interest from a number of major US waterfront cities including Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Miami, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego.[80]

Artifacts

Interior décor included a children's playroom designed by Edward Meshekoff.[81] Other artwork was designed by Charles Gilbert of Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana. His work included glass panels that divided the ballroom into sections. The panels were etched with sea creatures and plants which were highlighted with gold and silver leafing.[82]

The ship used four 60,000 lb (27,000 kg) manganese bronze propellers, two four-bladed screws outboard, and two inboard five-bladed. One of the four-bladed propellers is mounted at the entrance to the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City, while the other is mounted outside the American Merchant Marine Museum on the grounds of the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York. The starboard-side five-bladed propeller is mounted near the waterfront at SUNY Maritime College in Fort Schuyler, New York, while the other is at the entrance of the Mariner's Museum in Newport News, Virginia, mounted on an original 63 ft (19 m) long drive shaft.[83]

The ship's bell is kept in the clock tower on the campus of Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virgina. It is used to celebrate special events, including being rung by incoming freshman and by outgoing graduates.[84]

Speed records

With both the eastbound and westbound speed records, the United States obtained the Blue Riband which marked the first time a US-flagged ship had held the record since the SS Baltic claimed the prize 100 years earlier. United States maintained a 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) crossing speed on the North Atlantic in a service career that lasted 17 years. United States remained unchallenged for the Blue Riband throughout her career. During this period the fast trans-Atlantic passenger trade moved to air travel, and many regard the story of the Blue Riband as having ended with the United States.[85] Her east-bound record has since been broken several times (first, in 1986, by Virgin Atlantic Challenger II), and her west-bound record was broken in 1990 by Destriero, but these vessels were not passenger-carrying ocean liners. The Hales Trophy itself was lost in 1990 to Hoverspeed Great Britain, setting a new eastbound speed record for a commercial vessel.

Gallery

.jpg.webp) SS United States at sea, 1950s

SS United States at sea, 1950s Sun deck of SS United States, 1964 eastbound voyage

Sun deck of SS United States, 1964 eastbound voyage SS United States disembarking at Le Havre, 1964

SS United States disembarking at Le Havre, 1964 SS United States in dock at Pier 86 in New York the morning of July 31, 1964 sailing to Le Havre and Southampton

SS United States in dock at Pier 86 in New York the morning of July 31, 1964 sailing to Le Havre and Southampton SS United States laid up in Hampton Roads, 1989

SS United States laid up in Hampton Roads, 1989 SS United States docked on the Delaware River, Philadelphia, 2006

SS United States docked on the Delaware River, Philadelphia, 2006 SS United States bow at Pier 82, Philadelphia, 2017

SS United States bow at Pier 82, Philadelphia, 2017 Commodore Alexanderson

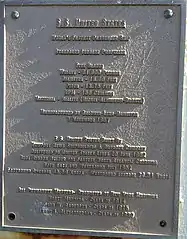

Commodore Alexanderson Details of ship's performance

Details of ship's performance Prop, looking to the northwest. Throgs Neck Bridge in background.

Prop, looking to the northwest. Throgs Neck Bridge in background.

See also

- SS Constitution

- SS Independence

- SS America (1939)

- SS United States: Lady in Waiting, a 2008 documentary

References

- Ujifusa, Steven (July 2012). A Man and his Ship. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-4516-4507-1.

- Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2020). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved September 22, 2020. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- Cudahy, Brian J. (February 1997). Around Manhattan Island and Other Tales of Maritime NY. Fordham University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8232-1761-8. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Horne, George (June 24, 1951). "Biggest US Liner 'Launched' in Dock; New Superliner After Being Christened Yesterday". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2012.(subscription required)

- Weinraub, Bernard (November 15, 1969). "Liner United States Laid Up; Competition From Jets a Factor; The United States Cancels Voyages and Is Laid Up". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2012.(subscription required)

- Koeppel, Dan (June 2008). "World's Fastest Superliner Awaits Rebirth—or the Scrap Yard". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- Griffin, John (February 1, 2011). "Save Our Ship: Passionate Preservationists Buy a National Treasure". ABC News. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "Retirement and Layup". SS United States Conservancy. 2011. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Adam Leposa (July 19, 2017). "SS United States Gets Last-Minute Reprieve". www.travelagentcentral.com. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "SS United States Receives $100,000 Donation". SS United States Conservancy. July 29, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- "The Great Oceanliners (Flip through website for reference)". Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "HISTORY: DESIGN & LAUNCH – SS United States Conservancy".

- "SS United States Saved, Perhaps to Sail Once More".

- "Steinway Baby Grand Piano from America's Flagship Now on Public Display". SS United States Conservancy.

- "Early Years". SS United States Conservancy. 2012. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Life and Times of the SS United States". The Big U: The Story of the SS United States. ssunitedstates-film.com. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- Dempewolff, Richard F. (June 1952). "America Bids for the Atlantic Blue Ribbon". Popular Mechanics: 81–87, 252, 254. ISSN 0032-4558. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "SS United States". ss-united-states.com. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "Designing and Constructing Superliner SS United States". ss-united-states.net. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- Driscoll, Larry (2009). "The Race for the Blue Riband". Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- "Atlantic Riband for America". The Times. London. July 8, 1952. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved April 27, 2017 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- NY Times (November 13, 1952). Ship speed trophy is presented here.

- Mimi Sheller (February 14, 2014). Aluminum Dreams: The Making of Light Modernity. MIT Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-262-02682-6.

- Mark G. Carbonaro (March 1991). "Fast Ferry". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- McKesson, Chris B., ed. (February 13, 1998). "Hull Form and Propulsor Technology for High Speed Sealift" (PDF). John J. McMullen Associates, Inc. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2005. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- "United States – Passenger Ship, IMO: 5373476". Vesselfinder.com. Retrieved October 29, 2020. This page gives a list of registered owners of the ship.

- "Times Daily – Google News Archive Search". Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- "Richard Hadley, 80; Planned Floating Condos for Ocean Line". The New York Times. April 15, 2002.

- Moore, John, Capt., RN, FRGS, editor, "Jane's Fighting Ships, 1987-88", Jane's Publishing Company Limited, London, UK, 1987, ISBN 0-7106-0842-X, page 790.

- "S.S. United States Sold to Turkish-Backed Group". Daily News. April 29, 1992.

- "$2.6 million bid wins SS United States International group plans renovation". The Baltimore Sun. April 28, 1992.

- "Асбестовый след корабля "Юнайтед Стейтс"". July 12, 2007.

- "Famed Liner's Moving, But There's No Money Yet For A Huge Fixup Will Ship Make City Seasick?". Philadelphia Daily News. August 15, 1996. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014.

- "S.S. UNITED STATES, The Turkish Years 1992–1996: What Might Have Been". maritimematters.com.

- Deflitch, Gerard (September 28, 2003). "S.S. United States may get chance to relive glory days". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

- David Tyler (February 28, 2007). "Return of 'Big U' delayed by problems with Pride of America". professionalmariner.com. Navigator Publishing LLC. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- "Those Three Two Stackers". Maritime Matters. May 24, 2006. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Morris, Rob (March 1, 2011). "Windmill Point Set to Go Out in a Blaze of Glory". Outer Banks Voice. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- Niemelä, Teijo (February 11, 2009). "SS United States may be offered for sale". Cruise Business Online. Cruise Media Oy Ltd. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "United States impending sale?". Maritime Matters. February 10, 2009. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- "Our History". SS United States Conservancy. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- Moran, Robert (July 30, 2009). "Phila. philanthropist to aid purchase of iconic ship". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia Newspapers LLC. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- "SS United States: America's Ship of State". SS United States Trust. July 4, 2009. Archived from the original on March 24, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- Ujifusa, Steven B. (March 3, 2010). "SS United States now in grave peril". PlanPhilly. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Fund Aims To Save S.S. United States". Myfoxphilly.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- Julie Shaw (January 29, 2016). "Is SS United States shipping out for New York?". Philly.com. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- Pesta, Jesse (July 1, 2010). "Famed Liner Steers Clear of Scrapyard". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 2, 2010. (subscription required)

- Cox, Martin (June 30, 2010). "Preservationists Perched To Buy SS UNITED STATES". Maritime Matters. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "POWERSHIPS FALL 2010". Steamship Historical Society of America. Fall 2010. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- Wittkowski, Donald (December 16, 2010). "Gambling panel revokes license for proposed Foxwoods casino project in Philadelphia". The Press of Atlantic City. The Press of Atlantic City Media Group. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- "Video of February 1 Title Transfer Event". SS United States Conservancy. February 9, 2011. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- Knego, Peter (March 16, 2011). "SS United States Latest". Maritime Matters. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "An Update From Conservancy Executive Director Dan McSweeney". SS United States Conservancy. August 5, 2011. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "Work Begins to Prepare the SS United States for Future Redevelopment". SS United States Conservancy. February 7, 2012. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "SS United States Redevelopment Project Releases Request for Qualifications" (Press release). SS United States Conservancy. April 5, 2012. Archived from the original on September 3, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "New Online Campaign Launches to Save the United States" (Press release). SS United States Conservancy. July 11, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- "Save the United States". SS United States Conservancy. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "SS United States To be "Repurposed"". Cruise Industry News. April 5, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "SS United States is being prepared for a new life". Associated Press. November 28, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "Will the SS United States find new life in 2014?". philly.com. January 6, 2014. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "America's flagship: Admirers of SS United States send an S.O.S." america.aljazeera.com. August 12, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- "The World's Fastest Ocean Liner May Be Restored to Sail Again". National Geographic News. February 8, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- Backwell, George (September 4, 2014). "SS United States Supporters Push for NY Return". Marine Link. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- "Encouraging New SS UNITED STATES Developments". maritimematters.com. December 15, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- "Agreement reached to redevelop SS United States". www.bizjournals.com. December 16, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- "SS United States gains $250,000 donation". Philly.com. February 11, 2015. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "Friends of the S.S. United States Send Out a Last S.O.S." The New York Times. October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- "Donations Help the S.S. United States Fend Off the Scrapyard". msn.com. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- "Can the SS United States again sail the seas?". philly.com. February 4, 2016. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "S.S. United States, Historic Ocean Liner of Trans-Atlantic Heyday, May Sail Again". The New York Times. February 4, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- "SS United States getting artifact donations from Mariners' Museum, others". Dailypress. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- "Crystal Drops SS United States Project". Cruise Industry News. August 5, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- Pesta, Jesse (August 6, 2016). "The S.S. United States Won't Take to the Seas Again After All". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- Adomaitis, Greg (August 8, 2016). "Abandoned ship: Deal to save SS United States 'too challenging'". NJ.com. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- Trina Thompson (January 26, 2018). "Once-majestic cruise ship, the S.S. United States, could be 'America's Flagship' once again". Fox News. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- "Leading Rotterdam Ship Repair & Conversion Firm Welcomed by Conservancy". wearetheunitedstates.org. SS United States Conservancy. September 20, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- Susan Gibbs (December 10, 2018). "Breaking News: New Agreement with RXR Realty". wearetheunitedstates.org. SS United States Conservancy. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- Jacob Adelman (December 12, 2018). "NYC developer with Manhattan pier project in deal to explore reviving SS United States". philly.com. Philly.com/Philadelphia Media Network (Digital), LLC. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- The Maritime Executive (March 11, 2020). "U.S. Cities Offered SS United States as Cultural Space". Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Dunlap, David (March 9, 2016). "Beloved Anachronisms, Times Square Mosaics of the City May Be Preserved". New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Steven Ujifusa (June 4, 2013). A Man and His Ship: America's Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the S.S. United States. Simon and Schuster. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-4516-4509-5.

- "The SS United States' Preserved Propellers" (PDF). SS United States Conservancy. June 2014.

- "Traditions – Who We Are". Christopher Newport University. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Kludas, Arnold (April 2002). Record Breakers of the North Atlantic: The Blue Riband Liners, 1838–1952. Brassey, Inc. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-57488-458-6. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

Further reading

- Braynard, Frank Osborn (1968). By their works ye shall know them: the life and ships of William Francis Gibbs, 1886–1967. New York: Gibbs & Cox. OCLC 1192704.

- Braynard, Frank Osborn (June 2002). SS United States. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-56311-824-1.

- Britton, Andrew (2012). SS United States. Classic Liners series. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7953-8.

- Ujifusa, Steven (July 10, 2012). A Man and His Ship: America's Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the S.S. United States. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4507-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to IMO 5373476. |

| External image | |

|---|---|

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. PA-647, "SS United States"

- SS United States Conservancy, current owner of SS United States

- Williams, C. K. (April 16, 2007). "Poetry – The United States". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Information on SS United States from vesselfinder.com This page gives a list of registered owners of the ship.

- SS United States, archive of various stories from the united-states-lines.org website

- SS United States, ss-united-states.com, an outdated conservation website

- SS United States photographs, archive of the ssmaritime.com website

- SS United States photographs, maritimematters.com website

- 2007 news article from USA Today

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Queen Mary |

Holder of the Blue Riband (eastbound record) 1952–present |

Succeeded by None[1] |

| Blue Riband (westbound record) 1952–present | ||

| Preceded by Normandie |

Holder of the Hales Trophy 1952 – 1990 |

Succeeded by Hoverspeed Great Britain |

- The story of the Blue Riband is regarded by many as having ended with the United States (see Kludas p136). The east-bound record has been broken several times (first time in 1980), and west-bound record in 1990, but these vessels were not passenger-carrying ocean liners