SPAdes (software)

SPAdes (St. Petersburg genome assembler)[1] is a genome assembly algorithm which was designed for single cell and multi-cells bacterial data sets. Therefore, it might not be suitable for large genomes projects.[1][2]

| Developer(s) | St. Petersburg State University, Russia St. Petersburg Academic University, Russia University of California, San Diego, USA |

|---|---|

| Stable release | 3.12.0

/ May 14th, 2018 |

| Repository | |

| Operating system | Linux, Mac OS |

| Type | Bioinformatics |

| License | free use |

| Website | cab.spbu.ru/software/spades/ |

SPAdes works with Ion Torrent, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore, and Illumina paired-end, mate-pairs and single reads.[1] SPAdes has been integrated into Galaxy pipelines by Guy Lionel and Philip Mabon.[3]

Background

Studying the genome of single cells will help to track changes that occur in DNA over time or associated with exposure to different conditions. Additionally, many projects such as Human Microbiome Project and antibiotics discovery would greatly benefit from Single-cell sequencing (SCS).[4][5] SCS has an advantage over sequencing DNA extracted from large number of cells. The problem of averaging out the significant variations between cells can be overcome by using SCS.[6] Experimental and computational technologies are being optimized to allow researchers to sequence single cells. For instance, amplification of DNA extracted from a single cell is one of the experimental challenges. To maximize the accuracy and quality of SCS, a uniform DNA amplification is needed. It was demonstrated that using multiple annealing and looping-based amplification cycles (MALBAC) for DNA amplification generates less biasness compared to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or multiple displacement amplification (MDA).[7] Furthermore, it has been recognized that the challenges facing SCS are computational rather than experimental.[8] Currently available assembler, such as Velvet,[9] String Graph Assembler (SGA)[10] and EULER-SR,[11] were not designed to handle SCS assembly.[2] Assembly of single cell data is difficult due to non-uniform read coverage, variation in insert length, high levels of sequencing errors and chimeric reads.[8][12][13] Therefore, the new algorithmic approach, SPAdes, was designed to address these issues.

SPAdes assembly approach

SPAdes uses k-mers for building the initial de Bruijn graph and on following stages it performs graph-theoretical operations which are based on graph structure, coverage and sequence lengths. Moreover, it adjusts errors iteratively.[2] The stages of assembly in SPAdes are:[2]

- Stage 1: assembly graph construction. SPAdes employs multisized de Bruijn graph (See below), which detects and removes bulge/bubble and chimeric reads.

- Stage 2: k-bimer (pairs of k-mers) adjustment. Exact distances between k-mers in the genome (edges in the assembly graph) are estimated.

- Stage 3: paired assembly graph construction.

- Stage 4: contig construction. SPAdes outputs contigs and allows to map reads back to their positions in the assembly graph after graph simplification (backtracking).

Details on SPAdes assembly

SPAdes was designed to overcome the problems associated with the assembly of single cell data as follows:[2]

1. Non-uniform coverage. SPAdes utilizes multisized de Bruijn graph which allows employing different values of k. It has been suggested to use smaller values of k in low-coverage regions to minimize fragmentation, and larger values of k in high coverage regions to decrease repeat collapsing (Stage 1 above).

2. Variable insert sizes of paired-end reads. SPAdes employs the basic concept of paired de Bruijn graphs. However, paired de Bruijn works well on paired-end reads with fixed insert size. Therefore, SPAdes estimates 'distances' instead of using 'insert sizes'. Distance (d) of a paired-end read is defined as, for a read length L, d = insert size – L. By utilizing k-bimer adjustment approach, distances are exactly estimated. A k-bimer consisting of k-mers ‘α’ and ‘β’ together with the estimated distance between them in a genome (α|β,d). This approach breaks the paired–end reads into pairs of k-mers which are transformed to define pairs of edges (biedges) in the de Bruijn graphs. These sets of biedges are involved in the estimation of distances between edges paths between k-mers α and β. By clustering, the optimal distance estimate is chosen from each cluster (stage 2, above). To construct paired de Bruijn graph, the rectangle graphs are employed in SPAdes (stage 3). Rectangle graphs approach was first introduced in 2012[15] to construct paired de Bruijn graphs with doubtful distances.

3. Bulge, tips and chimeras. Bulges and tips occur due to errors in the middle and ends of reads, respectively. A chimeric connection joins two unrelated substrings of the genome. SPAdes identifies these based on graph topology, the length and coverage of the non-branching paths included in them. SPAdes keeps a data structure to be able to backtrack all corrections or removals.

SPAdes modifies the previously used bulge removal approach[16] and iterative de Bruijn graph approach from Peng et al (2010)[17] and creates a new approach called ‘‘bulge corremoval’’, which stands for bulge correction and removal. The bulge corremoval algorithm can be summarized as follows: a simple bulge is formed by two small and similar paths (P and Q) connecting the same hubs. If P is a non-branching path (h-path), then SPAdes maps every edge in P to an edge projection in Q and removes P from the graph, as a result the coverage of Q increases. Unlike other assemblers, which use a fixed coverage cut-off bulge removal, SPAdes removes or projects the h-paths with low coverage step by step. This is achieved by employing gradually increasing cut-off thresholds and iterating through all h-paths in increasing order of coverage (for bulge corremoval and chimeric removal) or length (for tip removal). Moreover, in order to guarantee that no new sources/sinks are introduced to the graph, SPAdes deletes an h-path (in chimeric h-path removal) or projects (in bulge corremoval) only if its start and end vertices have at least two outgoing and ingoing edges. This helps to remove low coverage h-paths occurring from sequencing errors and chimeric reads but not from repeats.

SPAdes pipelines and performance

SPAdes is composed of the following tools:[1]

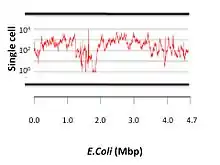

- Read error correction tool, BayesHammer (for Illumina data) and IonHammer (for IonTorrent data) .[14] In traditional error correction, rare k-mers are considered errors. This can not be applied for SCS because of non-uniform coverage. Therefore, BayesHammer employs probabilistic subclustering which examine multiple central nucleotide, which will be better covered than others, of similar k-mers .[14] It was claimed that for Escherichia coli (E. coli) single cell data set, BayesHammer runs in about 75 min, takes up to 10 Gb of RAM to carry out read error correction and requires 10 Gb additional disk space for temporary files.

- Iterative short-read genome assembler, SPAdes. For the same data set, this step runs for ~ 75 min. It takes ~ 40% of this time to perform stage 1 (see SPAdes assembly approach above) when using three iterations (k=22, 34 and 56), and ~ 45%, 14% and 1% for completing stages 2, 3 and 4, respectively. It also takes up to 5 Gb of RAM to perform assembly and needs 8 Gb additional disk space.

- Mismatch corrector (which uses the BWA tool). This module requires the longest time (~ 120 min) and the largest additional disk space (~21 Gb) for temporary files. It takes up to 9 Gb RAM to complete mismatch correction of assembled E. coli single cell data set.

- Module for assembling highly polymorphic diploid genomes, dipSPAdes. dipSPAdes constructs longer contigs by taking advantage of divergence between haplomes in repetitive genome regions. Afterwards, it produces consensus contigs construction and performs haplotype assembly.

Comparing assemblers

A study[18] compared several genome assemblers on single cell E. coli samples. These assemblers are EULER-SR,[11] Velvet,[9] SOAPdenovo,[19] Velvet-SC, EULER+ Velvet-SC (E+V-SC),[16] IDBA-UD[20] and SPAdes. It was demonstrated that IDBA-UD and SPAdes performed the best.[18] SPAdes had the largest NG50 (99,913, NG50 statistics is the same as the N50 except that the genome size is used rather than the assembly size).[21] Moreover, using E. coli reference genome,[22] SPAdes assembled the highest percentage of genome (97%) and the highest number of complete genes (4,071 out of 4,324).[18] The assemblers’ performances were as follows:[18]

- Number of contigs:

IDBA-UD < Velvet < E+V-SC < SPAdes < EULER-SR < Velvet-SC < SOAPdenovo

- NG50

SPAdes > IDBA-UD >>> E+V-SC > EULER-SR >Velvet >Velvet-SC > SOAPdenovo

- Largest contig:

IDBA-UD > SPAdes > > EULER-SR > Velvet= E+V-SC > Velvet-SC > SOAPdenovo

- Mapped genome (%):

SPAdes > IDBA-UD > E+V-SC > Velvet-SC > EULER-SR > SOAPdenovo > Velvet

- Number of misassemblies:

E+V-SC = Velvet = Velvet-SC < SOAPdenovo < IDBA-UD < SPADes < EULER-SR

See also

References

- http://spades.bioinf.spbau.ru/release3.0.0/manual.html

- Bankevich A; Nurk S; Antipov D; Gurevich AA; Dvorkin M; Kulikov AS; Lesin VM; Nikolenko SI; Pham S; Prjibelski AD; Pyshkin AV; Sirotkin AV; Vyahhi N; Tesler G; Alekseyev MA; Pevzner PA. (2012). "SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing". Journal of Computational Biology. 19 (5): 455–477. doi:10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. PMC 3342519. PMID 22506599.

- Galaxy tool shed

- Gill S; Pop M; Deboy R; Eckburg P; Turnbaugh P; Samuel B; Gordon J; Relman D; Fraser-Liggett C; Nelson K (2006). "Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome". Science. 312 (5778): 1355–1359. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1355G. doi:10.1126/science.1124234. PMC 3027896. PMID 16741115.

- Li J; Vederas J (2009). "Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless frontier?" (PDF). Science. 325 (5937): 161–165. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..161L. doi:10.1126/science.1168243. PMID 19589993. S2CID 206517350.

- Lu S; Zong C; Fan W; Yang M; Li J; Chapman A; Zhu P; Hu X; Xu L; Yan L; F B; Qiao J; Tang F; Li R; Xie X (2012). "Probing meiotic recombination and aneuploidy of single sperm cells by whole-genome sequencing". Science. 338 (6114): 1627–1630. Bibcode:2012Sci...338.1627L. doi:10.1126/science.1229112. PMC 3590491. PMID 23258895.

- http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2013/01/one-cell-is-all-you-need/

- Rodrigue S; Malmstrom RR; Berlin AM; Birren BW; Henn MR; Chisholm SW (2009). "Whole genome amplification and de novo assembly of single bacterial cells". PLOS ONE. 4 (9): e6864. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.6864R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006864. PMC 2731171. PMID 19724646.

- Zerbino D; Birney E (2008). "Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs". Genome Research. 18 (5): 821–829. doi:10.1101/gr.074492.107. PMC 2336801. PMID 18349386.

- Simpson JT; Durbin R (2012). "Efficient de novo assembly of large genomes using compressed data structures". Genome Research. 22 (3): 549–556. doi:10.1101/gr.126953.111. PMC 3290790. PMID 22156294.

- Pevzner PA; Tang H; Waterman MS (2001). "An Eulerian path approach to DNA fragment assembly". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (17): 9748–9753. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.9748P. doi:10.1073/pnas.171285098. PMC 55524. PMID 11504945.

- Medvedev P; Scott E; Kakaradov B; Pevzner P (2011). "Error correction of high-throughput sequencing datasets with non-uniform coverage" (PDF). Bioinformatics. 27 (13): i137–141. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr208. PMC 3117386. PMID 21685062.

- Ishoey T; Woyke T; Stepanauskas R; Novotny M; Lasken RS (2008). "Genomic sequencing of single microbial cells from environmental samples". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 11 (3): 198–204. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2008.05.006. PMC 3635501. PMID 18550420.

- Nikolenko SI; Korobeynikov AI; Alekseyev MA. (2012). "BayesHammer: Bayesian clustering for error correction in single-cell sequencing" (PDF). BMC Genomics. 14 (Suppl 1): S7. arXiv:1211.2756. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-S1-S7. PMC 3549815. PMID 23368723.

- Vyahhi N; Pham SK; Pevzner P (2012). From de Bruijn graphs to rectangle graphs for genome assembly. Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 7534. pp. 249–261. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-33122-0_20. ISBN 978-3-642-33121-3.

- Chitsaz H; Yee-Greenbaum JL; Tesler G; Lombardo MJ; Dupont CL; Badger JH; Novotny M; Rusch DB; Fraser LJ; Gormley NA; Schulz-Trieglaff O; Smith GP; Evers DJ; Pevzner PA; Lasken RS (2011). "Efficient de novo assembly of single-cell bacterial genomes from short-read data sets". Nat Biotechnol. 29 (10): 915–921. doi:10.1038/nbt.1966. PMC 3558281. PMID 21926975.

- Peng Y.; Leung H.C.M.; Yiu S.-M; Chin FYL (2010). IDBA—a practical iterative de Bruijn graph de novo assembler. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 6044. pp. 426–440. Bibcode:2010LNCS.6044..426P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.157.195. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12683-3_28. hdl:10722/129571. ISBN 978-3-642-12682-6.

- Gurevich A; Saveliev V; Vyahhi N; Tesler G (2013). "QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies" (PDF). Bioinformatics. 29 (8): 1072–1075. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. PMC 3624806. PMID 23422339.

- Li R; Zhu H; Ruan J; Qian W; Fang X; Shi Z; Li Y; Li S; Shan G; Kristiansen K; Li S; Yang H; Wang J; Wang J (2010). "De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing" (PDF). Genome Research. 20 (2): 265–272. doi:10.1101/gr.097261.109. PMC 2813482. PMID 20019144.

- Peng Y; Leung HCM; Yiu SM; Chin FYL (2012). "IDBA-UD: a de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth" (PDF). Bioinformatics. 28 (11): 1–8. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts174. PMID 22495754.

- http://bioinf.spbau.ru/spades/

- Blattner FR; Plunkett G; Bloch C; Perna N; Burland V; Riley M; Collado-Vides J; Glasner J; Rode C; Mayhew G; Gregor J; Davis N; Kirkpatrick H; Goeden M; Rose D; Mau B; Shao Y (1997). "The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12". Science. 277 (5331): 1453–1462. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. PMID 9278503.