Rossia

Rossia is a genus of 10 species of benthic bobtail squid in the family Sepioidae found in all oceans. They live at depths greater than 50 m (164 ft) and can grow up to 9 cm (3.5 in.) in mantle length.[2] This genus was first discovered in 1832 by Sir John Ross and his nephew James Clark Ross in the Arctic Seas, showing a resemblance to another genus under the same family, Sepiola. After returning from their expedition, Sir Richard Owen officially classified Rossia to be a new genus, naming it after Sir John and James Clark Ross. [3]

| Rossia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rossia glaucopis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Rossia |

Description

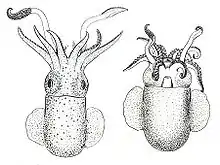

Rossia are categorized under the subfamily Rossiinae, which are identified by their short mantles and lack of ventral shield due to the unextended anterior ventral edge of the mantle.[4]

Rossia are distinguished by their dome-shaped mantles. which are not fused to their head.[2] They are shorter in length compared to many other bobtail squid, with mantle length varying from 1.4 cm (0.5 in) to 9 cm (3.5 in). Males do not grow to be as large as females.[2]

Each squid under genus Rossia have broadly separated fins with free anterior and posterior lobes.[5] Its tentacular club is expanded, with club suckers in series of 6 to 12 and no enlarged suckers are found on the lateral arms.[4] They lack photophores, but do possess functioning ink sacs. They also have small internal, chitinous pens.[2][6]

Distribution and habitat

Rossia are distributed throughout marine, benthic habitats worldwide. Most are commonly found in sandy or muddy bottoms on the seafloor. There is currently an insufficient amount of information to know the conservation status of Rossia.

| Species name | Common name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Rossia brachyura[2] | Short-tailed Bobtail Squid | Tropical western Atlantic, commonly the Greater and Lesser Antilles. |

| Rossia bullisi[7] | Gulf Bobtail Squid | Predominately in the Gulf of Mexico. From eastern Texas to the Bahamas. |

| Rossia glaucopis[2] | Chilean Bobtail Squid | Southeastern Pacific Ocean, predominately Chile. |

| Rossia macrosoma[8] | Stout Bobtail Squid | Coasts of Great Britain and Ireland. Found in depths from 50 to 600 m. |

| Rossia megaptera[2] | Big-fin Bobtail Squid | Northwestern Atlantic, from Greenland to New York. Found in depths ranging from 179- 1536 m. |

| Rossia moelleri[2] | Arctic Bobtail Squid | Northern Atlantic and Arctic oceans. Depth range from 17 to 250 m. |

| Rossia mollicella[2] | Mushroom-hat Bobtail Squid | Western North Pacific along Japanese coast. Found at depths on the outer shelf from 729 to 805m. |

| Rossia pacifica[2] | Stubby Bobtail Squid | Northern Pacific Ocean, ranging from Asia to the Pacific Northwest of North America. Found at depths ranging from 20 to 1,350 m. |

| Rossia palpebrosa[2] | Warty Bobtail Squid | Tropical and Northern Atlantic Ocean. Depth ranges from 75 to 549 m. |

| Rossia tortugaensis[7] | Tortugas Bobtail Squid | Coast of Southern Florida, USA in the Strait of Florida. |

Behavior

Rossia commonly bury themselves in sand by excavating a hole from underneath them by forcefully blowing water out of their siphon and throwing sand over their mantle with their arms. When predators are near, they release ink and jet themselves out of the sand, allowing for escape.[9]

Feeding habits

For species that have been studied, Rossia's diet consists of shrimps and prawns, but they have sharp and hardened beak which allows them to consume small crabs, along with fish and other cephalopods. They often use two tentacles to grasp their prey.

Reproduction and development

Males perform a variety of acts to attract potential females partners for reproduction. Rossia commonly reproduce by internal fertilization. During mating, the male inserts the hectocotlyus into the mantle cavity of the female where fertilization takes place.[10]

Spawning takes place year round, where small egg masses are found on seaweed or smooth objects on the ocean floor. Male and female adults often die shortly after mating.[11]

Egg cases have a thick, dense outer layer to protect the embryos, and are an average of 10 mm in diameter; however, the egg does not expand with development, and the embryo grows inside the casing. [12] When the egg masses of Rossia are ready to hatch, they push the tip of the mantle against the casing to break it, followed by the rest of its body.[13]

References

- Barratt, I.; Allcock, L. (2012). "Rossia megaptera". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T162575A920117. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T162575A920117.en. Downloaded on 10 February 2018.

- Jereb, P; Roper, C.F.E. "Cephalopods of the World". FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes No. 4. 1: 183–187. ISSN 1020-8682.

- Ross, Sir John; Ross, Sir James Clark (1835). Narrative of a second voyage in search of a north-west passage, and of a residence in the Arctic regions during the years 1829, 1830, 1831, 1832, 1833. London: A.W. Webster. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.11196.

- Roper, C.F.E; Jereb, P. "Cephalopods of the World". FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes No 4. 2: 212–213. ISSN 1020-8682.

- Llano, George A.; Schmitt, Waldo L. (1967). Biology of the Antarctic Seas III. Washington D.C.: American Geophysical Union.

- Sanchez, Gustavo; Jolly, Jeffrey; Reid, Amanda; Sugimoto, Chikatoshi; Azama, Chika; Marletaz, Ferdinand; Simakov, Oleg; Rokhsar, Daniel S. (2019). "New bobtail squid (Sepiolidae: Sepiolinae) from the Ryukyu islands revealed by molecular and morphological analysis". Communications Biology. 2: 465. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0661-6. PMC 6906322. PMID 31840110.

- Voss, Gilbert L. (1956). "A Review of the Cephalopods of the Gulf of Mexico". www.ingentaconnect.com. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- "Species Distribution Map Viewer". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- Anderson, R.C.; Steele, Craig; Mather, J.A. "Burying and associated behaviors of Rossia pacifica (Cephalopoda : Sepiolidae)". Vie et Milieu. 54: 13–19.

- Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology: a function evolutionary approach. Belmont, CA: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. pp. 360–367.

- Rodrigues, Marcelo; Guerra, Angel; Garci, Manuel E.; Troncoso, Jesus Souza. "Mating Behavior of the Atlantic Bobtail Squid (Sepiola Atlantica (Cephalopoda: Sepiodidae)". Vie et Milieu- Life and Environment. 59: 271–275.

- Boletzky, S.; Boletzky, M. V. (1973). "Observations on the embryonic and early post-embryonic development ofRossia macrosoma (Mollusca, Cephalopoda)". Helgoländer Wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen. 25 (1): 135–161. Bibcode:1973HWM....25..135V. doi:10.1007/BF01609965. ISSN 0017-9957.

- Laptikhovsky, V.V.; Nigmatullin, C.M.; Hoving, H.J.T.; Onsoy, B.; Salman, A.; Zumholz, K; Shevtsov, G.A. (2008). "Reproductive strategies in female polar and deep-sea bobtail squid genera Rossia and Neorossia (Cephalopoda: Sepiolidae)". Polar Biology. 31 (12): 1499–1507. doi:10.1007/s00300-008-0490-4.