Richard Goldschmidt

Richard Benedict Goldschmidt (April 12, 1878 – April 24, 1958) was a German-born American geneticist. He is considered the first to attempt to integrate genetics, development, and evolution.[1] He pioneered understanding of reaction norms, genetic assimilation, dynamical genetics, sex determination, and heterochrony.[2] Controversially, Goldschmidt advanced a model of macroevolution through macromutations popularly known as the "Hopeful Monster" hypothesis.[3]

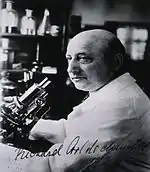

Richard Goldschmidt | |

|---|---|

In his laboratory | |

| Born | April 12, 1878 Frankfurt am Main, Germany |

| Died | April 24, 1958 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Heidelberg |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | genetics |

| Doctoral advisor | Otto Bütschli |

Goldschmidt also described the nervous system of the nematode, a piece of work that influenced Sydney Brenner to study the wiring diagram of Caenorhabditis elegans,[4] winning Brenner and his colleagues the Nobel Prize in 2002.

Childhood and education

Goldschmidt was born in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany to upper-middle class parents of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.[5] He had a classical education and entered the University of Heidelberg in 1896, where he became interested in natural history. From 1899 Goldschmidt studied anatomy and zoology at the University of Heidelberg with Otto Bütschli and Carl Gegenbaur. He received his Ph.D. under Bütschli in 1902, studying development of the trematode Polystomum.[2]

Career

In 1903 Goldschmidt began working as an assistant to Richard Hertwig at the University of Munich, where he continued his work on nematodes and their histology, including studies of the nervous system development of Ascaris and the anatomy of Amphioxus. He founded the histology journal Archiv für Zellforschung while working in Hertwig's laboratory. Under Hertwig's influence, he also began to take an interest in chromosome behavior and the new field of genetics.[2]

In 1909 Goldschmidt became professor at the University of Munich and, inspired by Wilhelm Johannsen's genetics treatise Elemente der exakten Erblichkeitslehre, began to study sex determination and other aspects of the genetics of the gypsy moth of which he was crossbreeding different races. He observed different stages of their sexual development. Some of the animals were neither male, nor female, nor hermaphrodites, but represented a whole spectrum of gynandromorphism. He named them 'intersex', and the phenomenon accordingly 'intersexuality' (Intersexualität).[6] His studies of the gypsy moth, which culminated in his 1934 monograph Lymantria, became the basis for his theory of sex determination, which he developed from 1911 until 1931.[2] Goldschmidt left Munich in 1914 for the position as head of the genetics section of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology.[7]

During a field trip to Japan in 1914 he was not able to return to Germany due to the outbreak of the First World War and got stranded in the United States. He ended up in an internment camp in Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia for "dangerous Germans".[8] After his release in 1918 he returned to Germany in 1919 and worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Sensing that it was unsafe for him to remain in Germany he emigrated to the United States in 1936, where he became professor at the University of California, Berkeley. During World War 2, the Nazi party published a propaganda poster entitled "Jewish World Domination" displaying the Goldschmidt family tree.[9]

Evolution

Goldschmidt was the first scientist to use the term "hopeful monster". He thought that small gradual changes could not bridge the divide between microevolution and macroevolution. In his book The Material Basis of Evolution (1940), he wrote "the change from species to species is not a change involving more and more additional atomistic changes, but a complete change of the primary pattern or reaction system into a new one, which afterwards may again produce intraspecific variation by micromutation." Goldschmidt believed the large changes in evolution were caused by macromutations (large mutations). His ideas about macromutations became known as the hopeful monster hypothesis, a type of saltational evolution, and attracted widespread ridicule.[10]

According to Goldschmidt, "biologists seem inclined to think that because they have not themselves seen a 'large' mutation, such a thing cannot be possible. But such a mutation need only be an event of the most extraordinary rarity to provide the world with the important material for evolution".[11] Goldschmidt believed that the neo-Darwinian view of gradual accumulation of small mutations was important but could account for variation only within species (microevolution) and was not a powerful enough source of evolutionary novelty to explain new species. Instead he believed that large genetic differences between species required profound "macro-mutations", a source for large genetic changes (macroevolution) which once in a while could occur as a "hopeful monster".[12][13]

Goldschmidt is usually referred to as a "non-Darwinian"; however, he did not object to the general microevolutionary principles of the Darwinians. He veered from the synthetic theory only in his belief that a new species develops suddenly through discontinuous variation, or macromutation. Goldschmidt presented his hypothesis when neo-Darwinism was becoming dominant in the 1940s and 1950s, and strongly protested against the strict gradualism of neo-Darwinian theorists. His ideas were accordingly seen as highly unorthodox by most scientists and were subjected to ridicule and scorn.[14] However, there has been a recent interest in the ideas of Goldschmidt in the field of evolutionary developmental biology, as some scientists, such as Günter Theißen and Scott F. Gilbert, are convinced he was not entirely wrong.[15][16] Goldschmidt presented two mechanisms by which hopeful monsters might work. One mechanism, involving "systemic mutations", rejected the classical gene concept and is no longer considered by modern science; however, his second mechanism involved "developmental macromutations" in "rate genes" or "controlling genes" that change early development and thus cause large effects in the adult phenotype. These kinds of mutations are similar to those considered in contemporary evolutionary developmental biology.[17]

Selected bibliography

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1917). "Intersexuality and the endocrine aspect of sex". Endocrinology. 1 (4): 433–456. doi:10.1210/endo-1-4-433.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1923). The Mechanism and Physiology of Sex Determination, Methuen & Co., London. (Translated by William Dakin)

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1929). "Experimentelle Mutation und das Problem der sogenannten Parallelinduktion. Versuche an Drosophila". Biologisches Zentralblatt. 49: 437–448.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1931). Die sexuellen Zwischenstufen, Springer, Berlin.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1934). "Lymantria". Bibliographia Genetica. 111: 1–185.

- Goldschmitdt, R. B. (1940). The Material Basis of Evolution, New Haven CT: Yale Univ.Press. ISBN 0-300-02823-7

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1946). "'An empirical evolutionary generalization' viewed from the standpoint of phenogenetics". American Naturalist. 80 (792): 305–17. doi:10.1086/281447. PMID 20982737.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1960) In and Out of the Ivory Tower, Univ. of Washington Press, Seattle.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1945). "Podoptera, a homoeotic mutant of Drosophila and the origin of the insect wing". Science (published Apr 13, 1945). 101 (2624): 389–390. doi:10.1126/science.101.2624.389. PMID 17780329.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1948). "New Facts on Sex Determination in Drosophila melanogaster". PNAS (published Jun 1948). 34 (6): 245–252. doi:10.1073/pnas.34.6.245. PMC 1079103. PMID 16588805.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1949). "Research and Politics". Science (published Mar 4, 1949). 109 (2827): 219–227. doi:10.1126/science.109.2827.219. PMID 17818053.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1949). "The intersexual males of the beaded minute combination in Drosophila melanogaster". PNAS (published Jun 15, 1949). 35 (6): 314–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.35.6.314. PMC 1063025. PMID 16588896.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (Oct 1949). "Phenocopies". Scientific American. 181 (4): 46–9. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1049-46. PMID 18148325.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1949). "The beaded minute-intersexes in Drosophila melanogaster Meig". J. Exp. Zool. (published Nov 1949). 112 (2): 233–301. doi:10.1002/jez.1401120205. PMID 15400338.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1949). "The interpretation of the triploid intersexes of Solenobia". Experientia (published Nov 15, 1949). 5 (11): 417–25. doi:10.1007/BF02165248. PMID 15395346.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1950). ""Repeats" and the Modern Theory of the Gene". PNAS (published Jul 1950). 36 (7): 365–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.36.7.365. PMC 1063204. PMID 15430313.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1951). "Chromosomes and genes". Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 16: 1–11. doi:10.1101/sqb.1951.016.01.003. PMID 14942726.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1954). "Different philosophies of genetics". Science (published May 21, 1954). 119 (3099): 703–10. doi:10.1126/science.119.3099.703. PMID 13168356.

- Goldschmidt, R. B.; Piternick, L K (1957). "The genetic background of chemically induced phenocopies in Drosophila". J. Exp. Zool. (published Jun 1957). 135 (1): 127–202. doi:10.1002/jez.1401350110. PMID 13481293.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1957). "A REMARKABLE ACTION OF THE MUTANT "RUDIMENTARY" IN Drosophila Melanogaster". PNAS (published Aug 15, 1957). 43 (8): 731–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.43.8.731. PMC 528529. PMID 16590077.

- Goldschmidt, R. B.; Piternick, L K (1957). "The genetic background of chemically induced phenocopies in Drosophila. II". J. Exp. Zool. (published Nov 1957). 136 (2): 201–228. doi:10.1002/jez.1401360202. PMID 13525585.

- Goldschmidt, R. B. (1957). "On Some Phenomena in Drosophila Related to So-Called Genic Conversion". PNAS (published Nov 15, 1957). 43 (11): 1019–1026. doi:10.1073/pnas.43.11.1019. PMC 528575. PMID 16590117.

References

- Hall, B. K. (2001), "Commentary", American Zoologist, 41 (4): 1049–1051, doi:10.1668/0003-1569(2001)041[1049:C]2.0.CO;2

- Dietrich, Michael R. (2003). Richard Goldschmidt: hopeful monsters and other 'heresies.' Nature Reviews Genetics 4 (Jan.): 68-74.

- Gould, S. J. (1977). "The Return of Hopeful Monsters." Natural History 86 (June/July): 24, 30.

- Rodney Cotterill Enchanted Looms: Conscious Networks in Brains and Computers 2000, p. 185

- Fangerau, Heiner (2005). "Goldschmidt, Richard Benedict". In Adam, Thomas; Kaufman, Will (eds.). Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. ABC–CLIO. pp. 455–456. ISBN 978-1-85109-628-2.

- Goldschmidt, Richard (1915). Vorläufige Mitteilung über weitere Versuche zur Vererbung und Bestimmung des Geschlechts. In: Biologisches Centralblatt, Band 35. Leipzig: Verlag Georg Thieme. pp. 565–570.

- Stern, Curt (1969). "Richard Benedict Goldschmidt". Perspect Biol Med. 12 (2): 179–203. doi:10.1353/pbm.1969.0028. PMID 4887419.

- Goldschmidt, Richard (1960). In and Out of the Ivory Tower. University of Washington Press. pp. 173–175. LCCN 60005653.

- "Imperial War Museums".

- Verne Grant The origin of adaptations 1963

- Prog Nucleic Acid Res&Molecular Bio by J N Davidson, Waldo E. Cohn, Serge N Timasheff, C H Hirs 1968, p. 67

- Nick Lane Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the meaning of life 2005, p. 30

- Eva Jablonka, Marion J. Lamb Epigenetic Inheritance and Evolution: The Lamarckian Dimension 1995 p. 222

- Donald R. Prothero Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters 2007, p. 99

- Theissen, G (2006). "The proper place of hopeful monsters in evolutionary biology". Theory Biosci. 124 (3–4): 349–369. doi:10.1016/j.thbio.2005.11.002. PMID 17046365.

- Scott F. Gilbert Developmental Biology Sinauer Associates; 6th edition, 2000

- Theissen, G (2010). "Homeosis of the angiosperm flower: Studies on three candidate cases of saltational evolution" (PDF). Palaeodiversity. 3 (Suppl): 131–139.