Rehabilitation policy

A rehabilitation policy is one intending to reform criminals rather than punish them and/or segregate them from the greater community.

History

Some early eighteenth and twentieth century prisons were proponents of rehabilitative policies. "Early American prisons, such as those at Auburn, Ossining, and Pittsburgh during the 1820s, implemented rehabilitative principles. These early programs isolated convicts in order to remove them from the temptations that had driven them to crime and to provide each inmate with time to listen to her conscience and reflect on her deeds...This belief that all convicts would return to their inherently good natures when removed from the corrupting influences of society gave way to more aggressive forms of treatment informed by the rise of social scientific studies into criminal behavior. Research in psychology, criminology, and sociology provided reformers with a deeper understanding of deviance and sharper tools with which to treat it. Rehabilitation became a science of reeducating the criminal with the values, attitudes, and skills necessary to live lawfully."[1] The philosophy of rehabilitation is that "not the offense but the character and reformability of the offender should determine his treatment."[2]

"Then, in the early 1970s, rehabilitation suffered a precipitous reversal of fortune. The larger disruptions in American society in this era prompted a general critique of the “state run” criminal justice system. Rehabilitation was blamed by liberals for allowing the state to act coercively against offenders, and was blamed by conservatives for allowing the state to act leniently toward offenders. In this context, the death knell of rehabilitation was seemingly sounded by Robert Martinson’s (1974b) influential 'nothing works' essay, which reported that few treatment programs reduced recidivism. This review of evaluation studies gave legitimacy to the antitreatment sentiments of the day; it ostensibly “proved” what everyone 'already knew': Rehabilitation did not work."[3]

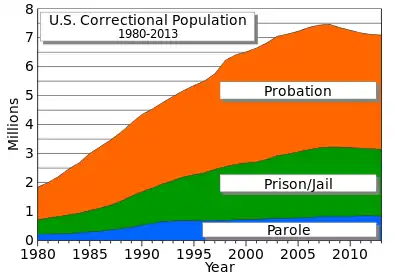

Deterrence (legal) and incapacitation ruled over the criminal justice system until the 90's where an unmanageable increase of the prisoner population created gaps where the benefits of rehabilitative policy could be discussed. "The increase of the prisoner population in the United States has resulted in shifting opinions on punishment vs. rehabilitation policies.[4]

Policies

Indeterminate sentencing

Indeterminate sentences are sentences where a judge indicates a minimum and maximum time for an offender to be imprisoned. The prisoner may be released anytime between the established minimum and maximum time. Indeterminate sentencing expanded discretion into the prison system so that prisoner rehabilitation could be analysed on the individual level. Indeterminate sentencing is personalized opposed to determinate sentencing which is standardized. "Advocates of determinate sentencing have argued that inmates support determinate sentencing because they strongly resent uncertainty of time to be served and sentencing inequity under indeterminate sentencing."[5] Because indeterminate sentencing expands discretion, offenders with similar crimes may serve vastly different prison times. Indeterminate sentencing exchanges equity of law for personalization of rehabilitation.

Parole

Parole is the conditional release of a prisoner who has served a part of their sentence back into the community under supervision and conditions that if violated will result in rearrest. There are 784,408 parolees in the United States[6] Although parole began as an effort to reintegrate offenders into the community, "...parole supervision has shifted ever more toward surveillance, drug testing, monitoring curfew and collecting restitution."[7] That is, the context of parole has shifted from reintegration with society into control of the individual on parole. Rather than parole being for rehabilitation, it has become in practice a less restrictive form of imprisonment. It is also argued that parole is a deterred prison entry program due to the high percentage of parolees that end up in prison due to violating terms of their parole. Many violated parole terms are technical infractions. That is, "noncriminal infractions" such as "failure to comply with curfews, pass alcohol and drug urinalysis screens, avoid contact with other offenders, maintain employment and/or report unemployment, attend meetings with probation and parole officers, make restitution payments and/or perform community service hours, and attend individual and/or group therapy meetings."[6] This is of particular concern since parole officer discretion determines parolee restrictions as well as the consequences for violating such restrictions.

Probation

Probation is a period of time where an offender lives under supervision and under a set of restrictions. Violations of these restrictions could result in arrest. Probation is typically an option for first time offenders with high rehabilitative capacity. At its core, it is "a substitute for prison", with the goal being to "spare the worthy first offender from the demoralizing influences of imprisonment and save him from recidivism".[8] In the United States, there are 4,162,536 probationers.[6] Probationers are supervised by probation officers just as parolees are supervised by parole officers. Probation officers have similar authority as parole officers do to restrict mobility, social contact, and mandate various other conditions and requirements. Probationers just like parolees are at high risk of imprisonment due to violation of their restrictions that may not be classified as criminal. In the United States, 40% of probationers were sent to jail or prison for technical and criminal violations.[6]

Expungement

Expungement is when an offense is removed from an offender's criminal record. In many states, however, an "expungement" does not erase or remove an offense.[9] Instead it converts it to a dismissal as opposed to a conviction. Minor offenses where rehabilitative success is met are deemed in some cases to be expungable in order for the offender to move past their mistake and live a completely normal life unrestricted by a past mistake.

The Second Chance for Ex-Offenders Act of 2007 allows non-violent offenders the possibility of having their records expunged. Criminal records limit what occupational and educational goals an individual may pursue, and it is noted that such restrictions may be correlated with recidivism. To fit the criteria of the act the offender must:

- ...never been convicted of a violent offense (including an offense under State law that would be a violent offense if it were Federal) and has never been convicted of a nonviolent offense other than the one for which expungement is sought;

- ...fulfilled all requirements of the sentence of the court in which conviction was obtained, including completion of any term of imprisonment or period of probation, meeting all conditions of a supervised release, and paying all fines;

- ...remained free from dependency on or abuse of alcohol or a controlled substance a minimum of 1 year and has been rehabilitated, to the satisfaction of the court referred to in section 3633(b), if so required by the terms of a supervised release;

- ...obtained a high school diploma or completed a high school equivalency program; and

- ...completed at least one year of community service, as determined by the court referred to in section 3633(b). R[10]

Separate juvenile justice system

Separate courts, detention facilities, and programs for juvenile offenders acknowledges that children, often not fully developed enough to know right from wrong, are deserving of separate rehabilitation efforts and processes. Prior to the late 1800s, child offenders were processed, trialled, and punished the same way as an adult would be. However, "By the mid-1920s, reforms separating children and adults who violated criminal laws into two separate court systems swept across the country."[11] Although there was a time that "...judges primarily concerned themselves with the best interests of the delinquent child, victims' rights statutes now require juvenile courts to balance the rehabilitative needs of the child with other competing interests such as accountability to the victim and restoration of communities impacted by crime."[12]

See also

References

- Smith, Nick (2008). "Rehabilitation" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Criminal Justice.

- Vanstone, Maurice (2008-11-01). "The International Origins and Initial Development of ProbationAn Early Example of Policy Transfer". The British Journal of Criminology. 48 (6): 735–755. doi:10.1093/bjc/azn070. ISSN 0007-0955.

- Cullen, Francis (2003). "Assessing Correctional Rehabilitation: Policy,Practice, and Prospects". Policies, Processes, and Decisions of the Criminal Justice System.

- Anger, Howard (2007). "March 2007". Criminal Justice In America.

- Larson, Calvin J.; Berg, Bruce L. (1989). "Inmates' Perceptions of Determinate and Indeterminate Sentences". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 7 (1): 127–137. doi:10.1002/bsl.2370070109.

- Kerbs, John J.; Jones, Mark; Jolley, Jennifer M. (2009). "Discretionary Decision Making by Probation and Parole Officers". Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 25 (4): 424–441. doi:10.1177/1043986209344556.

- Vrettos, James S (2010). "A strategy to end parole dependency". Dialectical Anthropology. 34 (4): 563–570. doi:10.1007/s10624-010-9171-0.

- Vanstone, Maurice (2008). "THE INTERNATIONAL ORIGINS AND INITIAL DEVELOPMENT OF PROBATION An Early Example of Policy Transfer". British Journal of Criminology. 48 (6): 735–755. doi:10.1093/bjc/azn070.

- "California Expungement FAQ: Learn about expunging a conviction in California". RGB Law Group. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- 110th Congress (2007). "Sec. 3632. Requirements for Expungement" (PDF). Second Chance for Ex-Offenders Act of 2007.

- Ritter, Michael J (2010). "Just (Juvenile Justice) Jargon: An Argument for Terminological Uniformity Between the Juvenile and Criminal Justice Systems". American Journal of Criminal Law. 37 (2): 221–240.

- Henning, Kristin (2009). "What's Wrong with Victims' Rights in Juvenile Court?: Retributive Versus Rehabilitative Systems of Justice". California Law Review. 97 (4): 1107–1170.